Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs): From Innate Immune Sensing to Therapeutic Targeting in Inflammatory Diseases

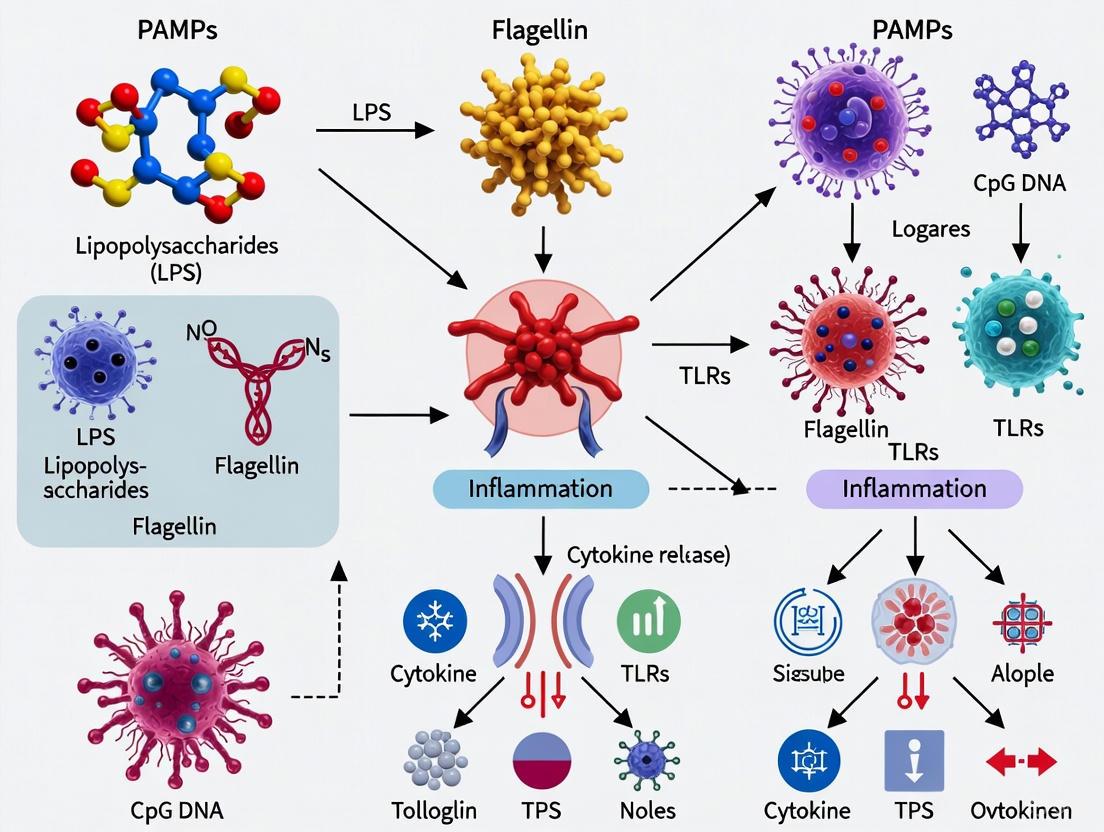

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) and their critical role in initiating inflammatory responses.

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs): From Innate Immune Sensing to Therapeutic Targeting in Inflammatory Diseases

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) and their critical role in initiating inflammatory responses. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational biology of PAMPs and their recognition by Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), detailing the subsequent signaling cascades that activate innate immunity. The content extends to methodological approaches for studying PAMP-PRR interactions, addresses challenges in discriminating pathogenic signals from non-threatening microbial noise, and compares immune responses across diverse pathogens. By synthesizing current research and emerging concepts like lifestyle-associated molecular patterns (LAMPs), this review aims to bridge fundamental immunology with translational applications for diagnosing and treating infectious, chronic inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases.

The First Line of Defense: Understanding PAMPs, PRRs, and the Innate Immune Alarm System

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) represent a cornerstone concept in immunology, providing the foundational mechanism by which innate immune systems detect invading microorganisms. These evolutionarily conserved molecular motifs are exclusively expressed by microbial pathogens and absent in the host, enabling precise discrimination between "self" and "non-self" [1] [2]. PAMPs are recognized by specialized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), triggering immediate antimicrobial and inflammatory responses while bridging innate and adaptive immunity [3] [4]. This technical review comprehensively examines PAMP classification, recognition mechanisms, signaling pathways, and experimental methodologies, with particular emphasis on recent advances including viability-associated PAMPs (vita-PAMPs) and biofilm-associated molecular patterns (BAMPs) [5] [6]. The elucidation of PAMP-PRR interactions continues to revolutionize our understanding of immune initiation and offers promising therapeutic avenues for inflammatory diseases, infections, and vaccine development.

The innate immune system constitutes the first line of defense against pathogenic microorganisms, employing a limited set of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect invariant molecular structures shared by broad classes of microbes [4]. These structures, termed Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs), represent essential components for microbial survival that remain evolutionarily conserved across pathogens but are distinct from host molecules [1] [2]. Charles Janeway first proposed the conceptual framework of PAMP recognition in 1989, hypothesizing that innate immune receptors must recognize conserved microbial products to trigger protective immunity [3] [2]. This revolutionary insight established the biological basis for how multicellular organisms distinguish infectious non-self from self.

PAMPs exhibit characteristic features that make them ideal recognition targets: (1) they are produced only by microorganisms, not by the host; (2) they recognize entire classes of pathogens rather than specific species; (3) they target molecular structures essential for microbial survival that cannot be easily discarded or mutated through evolution [2] [4]. The recognition of PAMPs by PRRs occurs in various cellular compartments, including plasma membranes, endosomal membranes, and the cytoplasm, enabling comprehensive immune surveillance against diverse pathogenic threats [3]. This initial recognition event triggers intracellular signaling cascades that culminate in the expression of proinflammatory molecules, initiating the early host response to infection and establishing a crucial bridge to adaptive immunity [4].

Major Classes of PAMPs and Their Recognition

PAMPs encompass diverse molecular structures including lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids derived from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa. The table below summarizes the major PAMP classes, their microbial origins, and their corresponding recognition receptors.

Table 1: Major Classes of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns

| PAMP Class | Specific Examples | Microbial Origin | Recognition Receptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Lipids | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) | Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria | TLR4/MD-2 (LPS), TLR2/TLR1 or TLR2/TLR6 (LTA) |

| Bacterial Proteins | Flagellin, Bacterial lipoproteins | Flagellated bacteria, Various pathogens | TLR5 (Flagellin), TLR2 heterodimers (Lipoproteins) |

| Bacterial Peptidoglycans | Peptidoglycan, Muramyl dipeptide | Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | TLR2, NOD1, NOD2 |

| Viral Nucleic Acids | dsRNA, ssRNA, CpG DNA | RNA and DNA viruses | TLR3 (dsRNA), TLR7/8 (ssRNA), TLR9 (CpG DNA) |

| Fungal Carbohydrates | Zymosan, β-Glucan | Fungi | TLR2/TLR6, Dectin-1 |

| Bacterial Nucleic Acids | CpG DNA, rRNA | Bacteria | TLR9 (CpG DNA), TLR13 (bacterial rRNA in mice) |

The cellular localization of PRRs determines their specific PAMP recognition capabilities. Membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs) situated on cell surfaces or within endosomes typically recognize extracellular PAMPs. For instance, TLR4 complexed with MD-2 recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, while TLR5 detects bacterial flagellin [1] [3]. Intracellular sensors including RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) detect microbial components that access the cytosol during infection. RIG-I and MDA5 sense viral RNA species, while NOD1 and NOD2 detect bacterial peptidoglycan fragments [1] [4]. This multi-compartmental surveillance system ensures comprehensive pathogen detection regardless of invasion route or replication strategy.

Recent conceptual expansions have refined the traditional PAMP paradigm. Viability-associated PAMPs (vita-PAMPs) represent a special class of microbial molecules that indicate metabolically active, replicating pathogens. Bacterial RNA exemplifies a vita-PAMP, as its synthesis ceases immediately upon microbial death, providing the immune system with a "warning sign" of active infection [5]. Similarly, biofilm-associated molecular patterns (BAMPs) constitute immunostimulatory molecules expressed specifically by biofilm-embedded bacteria, such as the simultaneous overexpression of alginate and Psl exopolysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms [6]. These specialized PAMP categories highlight the sophistication of immune recognition in distinguishing not merely microbial presence, but also metabolic state and lifestyle.

Pattern Recognition Receptors: Structure and Function

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) constitute a diverse protein family that specifically recognizes PAMPs and initiates downstream immune signaling. Based on protein domain homology and function, PRRs are classified into five major families: Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), and AIM2-like receptors (ALRs) [3]. These receptors share common structural organization featuring ligand recognition domains, intermediate domains, and effector domains that facilitate signal transduction upon PAMP engagement [3].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) represent the most extensively characterized PRR family. These type I transmembrane glycoproteins contain extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains responsible for PAMP recognition and intracellular Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domains that mediate downstream signaling [3]. Humans encode 10 functional TLRs (TLR1-TLR10), while mice express 12 (TLR1-TLR9, TLR11-TLR13) [3]. TLRs localize to distinct cellular compartments: certain TLRs (TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR10) reside on plasma membranes where they recognize microbial membrane components like lipids, lipoproteins, and proteins, while others (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9) localize to endosomal membranes where they primarily detect microbial nucleic acids [3]. This strategic compartmentalization enables recognition of diverse PAMP classes while minimizing inappropriate activation by host molecules.

Cytosolic PRRs provide critical surveillance against intracellular pathogens. RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), including RIG-I and MDA5, detect viral RNA in the cytoplasm. RIG-I recognizes short double-stranded RNA and RNA with 5'-triphosphates, while MDA5 senses long double-stranded RNA structures [1]. NOD-like receptors (NLRs) form large multi-protein complexes called inflammasomes that activate caspase-1 and process pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [3]. The AIM2-like receptor (ALR) family detects cytosolic DNA, initiating inflammasome assembly and type I interferon responses [3]. This diverse PRR arsenal ensures comprehensive pathogen detection across all cellular compartments.

Table 2: Major Pattern Recognition Receptor Families and Their Characteristics

| PRR Family | Representative Members | Localization | Structural Features | PAMP Ligands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) | TLR4, TLR3, TLR9 | Plasma membrane, Endosomes | LRR extracellular/endosomal domain, TIR intracellular domain | LPS (TLR4), dsRNA (TLR3), CpG DNA (TLR9) |

| RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs) | RIG-I, MDA5 | Cytoplasm | Caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs), DExD/H-box RNA helicase domain | Short dsRNA/5'-triphosphate RNA (RIG-I), long dsRNA (MDA5) |

| NOD-like Receptors (NLRs) | NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3 | Cytoplasm | CARD, PYD, or BIR domains; NACHT domain; LRR domain | Peptidoglycan fragments (NOD1/NOD2), various PAMPs/DAMPs (NLRP3) |

| C-type Lectin Receptors (CLRs) | Dectin-1, MR-CTLD4-7 | Plasma membrane | Carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) | β-glucans (Dectin-1), Psl/Pel EPS (MR-CTLD4-7) |

| AIM2-like Receptors (ALRs) | AIM2 | Cytoplasm | HIN-200 domain, PYD domain | Cytosolic DNA |

PAMP-Triggered Signaling Pathways and Immune Activation

PAMP recognition by PRRs initiates sophisticated intracellular signaling cascades that orchestrate antimicrobial and inflammatory responses. These pathways demonstrate remarkable specificity, with different PRR families engaging distinct adaptor molecules and activation kinetics to generate tailored immune responses against diverse pathogens.

TLR Signaling Pathways

TLR signaling bifurcates into MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways based on adaptor molecule utilization. Most TLRs (except TLR3) signal through the adaptor protein MyD88, ultimately activating NF-κB and MAPK pathways to induce proinflammatory cytokine production [3]. TLR3 exclusively utilizes the TRIF adaptor, while TLR4 employs both MyD88 and TRIF pathways [3]. TRIF-dependent signaling leads to IRF3 activation and type I interferon production, crucial for antiviral defense [3]. The specific signaling pathway engaged depends on both the TLR activated and the cell type involved, enabling customized immune responses against different pathogen classes.

Cytosolic PRR Signaling

Cytosolic RNA sensors including RIG-I and MDA5 signal through the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), activating IRF3/7 and NF-κB to induce type I interferons and proinflammatory cytokines [1] [5]. NLR family members detect various intracellular PAMPs and DAMPs: NOD1 and NOD2 engage RIP2 kinase to activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways, while NLRP3 forms inflammasome complexes that process IL-1β and IL-18 through caspase-1 activation [3]. DNA sensors like AIM2 form inflammasomes, while cGAS produces the second messenger cGAMP that activates STING and subsequent type I interferon responses [5].

The following diagram illustrates the major signaling pathways triggered by PAMP recognition:

The integration of these signaling pathways coordinates a multifaceted immune response characterized by: (1) production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) that activate immune cells and induce antimicrobial states; (2) secretion of type I interferons that establish antiviral defenses in neighboring cells; (3) increased expression of costimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells that facilitate adaptive immunity; and (4) induction of specialized cell death pathways (pyroptosis) that eliminate intracellular replication niches while promoting further inflammation [3] [4]. This coordinated response effectively contains infections while shaping subsequent adaptive immune mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols for PAMP Research

NETosis Induction and Quantification

Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation represents an important antimicrobial mechanism triggered by PAMP recognition. The following protocol details NETosis induction and quantification:

Isolation of Human Neutrophils:

- Collect peripheral blood from healthy donors using heparin or EDTA anticoagulant.

- Separate neutrophils using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque PLUS).

- Perform erythrocyte lysis using ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) buffer.

- Resuspend neutrophils in RPMI-1640 medium without serum at 1-5×10^6 cells/mL.

- Assess viability using trypan blue exclusion (>95% viability required).

NETosis Induction with PAMPs:

- Plate neutrophils on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips or tissue culture plates.

- Stimulate with purified PAMPs: LPS (100 ng/mL), Pam3CSK4 (1 μg/mL), or bacterial RNA (1-5 μg/mL).

- Include positive controls: PMA (100 nM) or ionomycin (1 μM).

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 2-4 hours.

- For inhibition studies, pre-treat with NADPH oxidase inhibitor (DPI, 10 μM) or PAD4 inhibitor (GSK484, 5 μM) for 1 hour before PAMP stimulation.

NET Quantification Methods:

- Immunofluorescence microscopy: Fix cells with 4% PFA, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, stain with anti-histone H3 (citrulline R2+R8+R17) antibody and anti-neutrophil elastase antibody, counterstain with DAPI. Quantify NET-forming cells as those exhibiting decondensed DNA colocalized with granular enzymes.

- SYTOX Green assay: Add cell-impermeable DNA dye SYTOX Green (5 μM) to culture supernatants. Measure fluorescence (excitation 504 nm, emission 523 nm) as indicator of extracellular DNA release.

- MPO-DNA complex ELISA: Capture NETs in supernatant using anti-MPO antibody, detect with anti-DNA peroxidase antibody and TMB substrate.

- Neutrophil elastase activity: Measure elastase activity in supernatants using N-methoxysuccinyl-AAPV-p-nitroanilide substrate (absorbance at 405 nm) [7].

Bacterial RNA Isolation and Transfection

Bacterial RNA serves as a prototypical vita-PAMP. The following protocol details its isolation and application in immune activation studies:

RNA Isolation from Bacteria:

- Culture bacteria to mid-logarithmic phase (OD₆₀₀ = 0.5-0.7).

- Stabilize RNA using RNA-protect Bacterial Reagent.

- Lyse bacteria using lysozyme (5 mg/mL) and proteinase K treatment.

- Isolve total RNA using commercial kits (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit) with DNase I treatment.

- Assess RNA quality (RNA Integrity Number >8.0) and quantity using spectrophotometry.

- Confirm absence of genomic DNA contamination by PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene.

Immune Cell Transfection and Stimulation:

- Culture immortalized macrophages (e.g., RAW264.7, THP-1) or primary bone marrow-derived macrophages in antibiotic-free medium.

- For TLR activation studies: Stimulate cells with extracellular bacterial RNA (1-5 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of chloroquine (20 μM) to inhibit endosomal acidification.

- For cytosolic RLR activation: Transfect cells with bacterial RNA using lipofectamine 2000 (1-2 μg RNA per 10⁶ cells).

- Collect supernatants at 6 hours (cytokine measurement) and 18 hours (type I IFN measurement).

- Analyze cytokine production via ELISA (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-β) and gene expression via RT-qPCR for interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAMP Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR Agonists | Ultrapure LPS (TLR4), Pam3CSK4 (TLR2/1), Poly(I:C) (TLR3), Imiquimod (TLR7) | PRR signaling studies, Immune cell activation | Verify purity (e.g., LAL testing for LPS), Use specific inhibitors to confirm receptor involvement |

| Cytosolic PRR Agonists | 3pRNA (RIG-I), Poly(I:C) HMW (MDA5), CDN (STING), dsDNA (AIM2/cGAS) | Intracellular pathogen recognition, Inflammasome activation | Optimize transfection method (lipofection, electroporation), Monitor cytotoxicity |

| PRR Inhibitors | TAK-242 (TLR4), Chloroquine (endosomal TLRs), BX795 (TBK1/IKKε), MCC950 (NLRP3) | Pathway validation, Therapeutic targeting | Assess specificity using multiple PRR agonists, Confirm inhibition of downstream signaling |

| Detection Antibodies | Phospho-specific IRF3, NF-κB p65, STAT1; Cytokine ELISA kits; Citrullinated histone H3 | Signaling pathway analysis, NETosis quantification | Validate species reactivity, Optimize staining conditions for phospho-epitopes |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary neutrophils/macrophages, THP-1, RAW264.7, HEK-Blue TLR reporter cells | Immune response characterization, Signaling studies | Differentiate THP-1 with PMA, Use primary cells for physiological relevance |

| Animal Models | TLR knockout mice, MYD88/TRIF knockout mice, Germ-free mice | In vivo validation, Host-pathogen interactions | Consider microbiota effects, Use appropriate infection models |

Research Implications and Therapeutic Applications

The elucidation of PAMP-PRR interactions has profound implications for understanding immune homeostasis, inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic development. Dysregulated PAMP recognition contributes to numerous pathologies: excessive TLR signaling drives septic shock, while inappropriate nucleic acid sensing underlies autoimmune disorders like lupus erythematosus [3] [7]. Conversely, defective PAMP recognition creates immunodeficiency states with increased infection susceptibility [4]. These insights have catalyzed novel therapeutic approaches targeting PAMP-PRR axes.

Vaccine adjuvants represent the most successful clinical application of PAMP research. TLR agonists including monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL, TLR4 agonist) and CpG oligonucleotides (TLR9 agonist) enhance vaccine efficacy by promoting dendritic cell maturation and robust adaptive immunity [1] [8]. Similarly, anticancer immunotherapies utilize PRR agonists to overcome immunosuppressive microenvironments: intratumoral injection of TLR9 agonists promotes antitumor immunity in lymphoma, while STING agonists demonstrate efficacy against solid tumors [1]. Anti-inflammatory therapies targeting PRR signaling include TLR4 antagonists for sepsis and NLRP3 inhibitors for gout and inflammatory bowel disease [3] [7]. The evolving understanding of vita-PAMPs and BAMPs offers further therapeutic opportunities for combating chronic infections and biofilm-associated diseases [5] [6].

Future research directions include: (1) elucidating the crosstalk between different PRR families in integrated immune responses; (2) characterizing novel PAMP classes from emerging pathogens; (3) developing tissue-specific PRR modulators to minimize systemic toxicity; and (4) exploring personalized immunotherapies based on PRR polymorphism profiles [3]. The continued dissection of PAMP recognition mechanisms will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic strategies against infection, cancer, and inflammatory disorders.

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns represent the fundamental language through which the immune system detects microbial invasion. These conserved molecular motifs enable rapid, nonspecific defense mechanisms while simultaneously instructing pathogen-specific adaptive immunity. The sophisticated PRR network that recognizes PAMPs demonstrates remarkable specificity despite its limited receptor repertoire, employing strategic localization, combinatorial signaling, and cross-regulatory mechanisms to generate appropriate inflammatory responses. Ongoing research continues to expand the PAMP paradigm through concepts like vita-PAMPs and BAMPs, refining our understanding of immune discrimination between viable and dead microorganisms, planktonic and biofilm growth states. The therapeutic translation of these insights is already yielding novel vaccine adjuvants, immunotherapies, and anti-inflammatory agents, highlighting the profound clinical implications of fundamental research into these universal danger signals. As our understanding of PAMP-PRR interactions deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate these pathways for therapeutic benefit across diverse disease contexts.

Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) represent the cornerstone of the innate immune system, serving as germline-encoded host sensors that provide the crucial first line of defense against pathogenic invasion [9] [10]. These receptors function as specialized cellular sentinels, continuously monitoring for conserved molecular structures known as Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) that are characteristic of diverse microbes but absent in the host [3] [9]. Additionally, PRRs detect Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) released from injured host cells during cellular stress, damage, or death [11] [9]. This dual recognition capability enables the immune system to respond effectively to both infectious threats and sterile injury, bridging innate detection with the initiation of adaptive immunity [3] [10].

The conceptual foundation for PRRs was established by Charles Janeway in 1989, who hypothesized that the innate immune system possesses a specific capacity to detect microbial infections through receptors that recognize molecular patterns unique to pathogens [9]. This paradigm was later expanded by Polly Matzinger's "danger model," which proposed that immune activation occurs in response to danger signals emanating from both pathogens and host-derived damage molecules [9]. The discovery of Toll-like receptors in Drosophila by Hoffmann and colleagues in 1996, followed by the identification of human TLR4 by Janeway and Medzhitov, provided molecular validation for these theoretical frameworks and launched extensive research into diverse PRR families [3] [9].

PRRs are strategically expressed on various immune cells—including macrophages, dendritic cells, monocytes, and neutrophils—as well as non-immune epithelial and endothelial cells [11] [10]. Through their recognition capabilities, PRRs initiate intracellular signaling cascades that trigger the production of proinflammatory cytokines, interferons, chemokines, and other mediators that collectively coordinate anti-pathogen responses, activate inflammatory pathways, and shape subsequent adaptive immunity [3] [11]. The strategic positioning of different PRR families throughout cellular compartments ensures comprehensive surveillance of extracellular, endosomal, and cytoplasmic spaces, creating a multi-layered defense network against invading pathogens and endogenous threats [9] [10].

PRR Classification and Structural Features

PRRs are categorized into distinct families based on their protein domain homology, subcellular localization, and ligand specificity. The major families include Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), and DNA sensors such as AIM2-like receptors (ALRs) and cGAS [3] [9] [10]. While these families differ in structure and function, they share a common architectural principle: most contain ligand recognition domains, intermediate domains, and effector domains that facilitate pathogen detection and signal transduction [3] [9].

Table 1: Major Pattern Recognition Receptor Families

| PRR Family | Localization | Representative Members | Structural Domains | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) | Cell surface & endosomal membranes | TLR1-TLR10 (humans) | Extracellular LRR, transmembrane, intracellular TIR | First discovered PRR family; form homo/heterodimers |

| NOD-like Receptors (NLRs) | Cytoplasm | NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3 | CARD, NOD/NACHT, LRR | Form inflammasomes; regulate caspase-1 activation |

| RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs) | Cytoplasm | RIG-I, MDA5, LGP2 | RNA helicase, CARD domains | Detect viral RNA; induce type I interferon production |

| C-type Lectin Receptors (CLRs) | Cell surface | Dectin-1, DC-SIGN, Mannose Receptor | Carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) | Recognize carbohydrate patterns; important for antifungal immunity |

| DNA Sensors | Cytoplasm & nucleus | cGAS, AIM2 | - | Detect mislocalized DNA; initiate STING pathway |

Membrane-bound PRRs include TLRs and CLRs, which surveil extracellular and endosomal compartments, while cytoplasmic PRRs encompass NLRs, RLRs, and various DNA sensors that monitor the intracellular environment for signs of invasion or damage [9] [10]. TLRs are type I transmembrane glycoproteins characterized by an extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain responsible for ligand binding, and an intracellular Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain that initiates signaling cascades [3] [11]. Different TLRs localize to distinct cellular compartments: TLR1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10 reside on the plasma membrane, while TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 are embedded in endosomal membranes where they encounter nucleic acids from internalized pathogens [3] [11].

NLRs and RLRs represent major cytoplasmic receptor families. NLRs typically contain a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain for ligand sensing, a central nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD/NACHT), and N-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARD) or pyrin domains (PYD) that mediate downstream signaling [9] [10]. RLRs—including RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2—feature DExD/H-box RNA helicase domains that enable recognition of viral RNA patterns, with RIG-I and MDA5 additionally containing CARD domains for signal transduction [9]. CLRs possess C-type lectin domains (CTLDs) that often recognize carbohydrate structures in a calcium-dependent manner, making them particularly important for detecting fungal pathogens [10].

PRR Ligand Recognition Mechanisms

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs)

PAMPs represent conserved molecular structures essential for microbial survival and pathogenicity, making them reliable indicators of infection [3] [12]. These invariant motifs differ fundamentally from host components, enabling the immune system to distinguish "self" from "non-self" with remarkable precision [3]. PAMPs encompass diverse molecular classes including bacterial cell wall components (LPS, peptidoglycan, lipopeptides), microbial nucleic acids (bacterial DNA, viral RNA), flagellar proteins, and fungal carbohydrates [12] [10]. Their conservation across pathogen classes allows for a limited repertoire of PRRs to detect a vast array of microorganisms [12].

Different PRR families exhibit specialized recognition capabilities for distinct PAMP categories. Surface TLRs (TLR1, 2, 4, 5, 6) primarily detect membrane components of pathogens, with TLR4 recognizing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria in complex with MD-2 protein [3] [11]. TLR2 forms heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6 to recognize a broad spectrum of bacterial lipopeptides and lipoproteins [11]. Endosomal TLRs (TLR3, 7, 8, 9) specialize in nucleic acid detection, with TLR3 binding double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) from viruses, while TLR7/8 recognize single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), and TLR9 identifies unmethylated CpG DNA motifs prevalent in bacterial genomes [3] [11].

Cytoplasmic PRRs survey the intracellular environment for signs of invasion. RLRs (RIG-I and MDA5) detect distinct viral RNA patterns: RIG-I recognizes short double-stranded RNA with 5'-triphosphate groups, while MDA5 senses longer dsRNA structures [9]. NLRs mainly recognize bacterial peptidoglycan derivatives, with NOD1 detecting meso-diaminopimelic acid (meso-DAP) from Gram-negative bacteria, and NOD2 responding to muramyl dipeptide (MDP) present in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [10]. CLRs such as Dectin-1 recognize β-glucans in fungal cell walls, while other CLRs bind mannose, fucose, or glucan patterns characteristic of various pathogens [10].

Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs)

Beyond pathogen detection, PRRs recognize endogenous danger signals known as DAMPs, which are released during cellular stress, damage, or necrotic death [11] [9]. DAMPs include * intracellular molecules that normally reside within cells but assume immunostimulatory properties when exposed to the extracellular environment* following tissue injury [9]. Common DAMPs include high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), histones, uric acid, extracellular ATP, hyaluronic acid fragments, heat shock proteins, and genomic DNA released from damaged nuclei or mitochondria [11] [9].

The recognition of DAMPs by PRRs initiates "sterile inflammation"—inflammatory responses in the absence of infection—that serves to eliminate damaged cells and initiate tissue repair processes [11]. However, excessive or persistent DAMP signaling can contribute to chronic inflammatory conditions, autoimmune diseases, and cancer progression [9]. This dual nature of DAMP recognition highlights the sophisticated balance PRRs maintain in distinguishing protective from pathological inflammation, with context-dependent outcomes determined by the magnitude, duration, and combination of signals received [9].

Table 2: Representative PAMPs, DAMPs, and Their PRRs

| Ligand Category | Specific Ligands | Recognizing PRRs | Cellular Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial PAMPs | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | TLR4/MD-2 | Gram-negative bacteria |

| Lipoteichoic acid | TLR2 | Gram-positive bacteria | |

| Flagellin | TLR5 | Flagellated bacteria | |

| Peptidoglycan fragments | NOD1, NOD2 | Bacterial cell walls | |

| Unmethylated CpG DNA | TLR9 | Bacterial DNA | |

| Viral PAMPs | Double-stranded RNA | TLR3, RIG-I, MDA5 | Viral replication intermediates |

| Single-stranded RNA | TLR7, TLR8 | RNA viruses | |

| 5'-triphosphate RNA | RIG-I | Negative-sense RNA viruses | |

| Fungal PAMPs | Zymosan | TLR2/Dectin-1 | Fungal cell walls |

| β-glucans | Dectin-1 | Fungal cell walls | |

| Mannans | MR, DC-SIGN | Fungal surfaces | |

| DAMPs | HMGB1 | TLR4, RAGE | Necrotic cells |

| Extracellular ATP | P2X7 receptor | Damaged cells | |

| Mitochondrial DNA | cGAS | Cellular damage | |

| Hyaluronic acid fragments | TLR4 | Extracellular matrix degradation |

Signaling Pathways and Immune Activation

TLR Signaling Pathways

TLR activation initiates signaling cascades that diverge into two principal pathways: the MyD88-dependent pathway utilized by all TLRs except TLR3, and the TRIF-dependent pathway employed by TLR3 and TLR4 [3] [10]. Upon ligand binding and receptor dimerization, TLRs recruit adaptor proteins through homophilic interactions between their TIR domains and those of the adaptors [3]. The MyD88-dependent pathway begins with the recruitment of the master adaptor MyD88, which subsequently recruits interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAK4, IRAK1, IRAK2) to form a signaling complex [10]. This complex interacts with TRAF6, leading to activation of TAK1 and subsequent induction of two key signaling branches: the NF-κB pathway and the MAP kinase pathway [10]. These pathways ultimately activate transcription factors that translocate to the nucleus and induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) and chemokines [3].

The TRIF-dependent pathway (also called the MyD88-independent pathway) is initiated by TLR3 and TLR4, resulting in the recruitment of the adaptor TRIF [10]. TRIF activates TBK1 and IKKε kinases, which phosphorylate IRF3, leading to IRF3 dimerization, nuclear translocation, and induction of type I interferon genes (IFN-α/β) [3]. Simultaneously, TRIF activates the same NF-κB and MAPK pathways as the MyD88-dependent route through RIP1 and TRAF6, providing complementary inflammatory signaling [10]. The specific adaptor usage and resulting gene expression profiles are tailored to the cellular context and pathogen threat, enabling customized immune responses.

Diagram 1: TLR Signaling Pathways - The MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways

NLR and RLR Signaling Pathways

NLR signaling typically converges on NF-κB and MAPK activation through the serine-threonine kinase RIP2, leading to inflammatory gene expression [10]. Certain NLRs (such as NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2) form multiprotein complexes called inflammasomes that serve as activation platforms for caspase-1 [9]. Active caspase-1 processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature, bioactive forms and cleaves gasdermin D to induce pyroptosis—an inflammatory form of cell death that eliminates infected cells [9].

RLR signaling is initiated when RIG-I or MDA5 detects viral RNA in the cytoplasm, triggering their interaction with the mitochondrial adaptor protein MAVS (also called IPS-1, VISA, or Cardif) [9]. MAVS activation nucleates the formation of large prion-like polymers that serve as signaling hubs, recruiting TRAF family members and activating IKK-related kinases TBK1 and IKKε, which phosphorylate IRF3 and IRF7 [9]. These phosphorylated IRFs dimerize and translocate to the nucleus to induce type I interferon gene expression, establishing an antiviral state in the cell and surrounding tissues [9]. Simultaneously, MAVS activates the IKK complex leading to NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine production [9].

Diagram 2: RLR and NLR Signaling Pathways - Antiviral and antibacterial immune responses

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

PRR Expression Analysis

Investigating PRR expression patterns across different cell types and conditions provides fundamental insights into their roles in immunity and disease. The most common methodologies include:

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR): Enables precise quantification of PRR mRNA expression levels in cells or tissues following pathogen challenge, cytokine stimulation, or under pathological conditions [13]. This approach allows researchers to correlate PRR expression changes with specific immune challenges. Experimental protocol: Extract total RNA using TRIzol or column-based methods, synthesize cDNA with reverse transcriptase, perform qPCR using gene-specific primers for target PRRs (e.g., TLRs, RLRs, NLRs), and normalize data using housekeeping genes (GAPDH, β-actin). Include no-template controls and standard curves for quantification.

Western Blotting: Detects and quantifies PRR protein expression, post-translational modifications, and cleavage events that regulate PRR activity [13]. This technique is essential for confirming that mRNA expression correlates with protein production and for assessing PRR activation states. Experimental protocol: Prepare cell lysates in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membranes, block with 5% BSA, incubate with primary antibodies against specific PRRs (e.g., anti-TLR4, anti-NOD2), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and detect using chemiluminescence substrates.

Flow Cytometry: Facilitates analysis of PRR surface expression on specific immune cell populations and permits correlation with activation markers or intracellular signaling molecules [13]. This approach is particularly valuable for heterogeneous cell samples. Experimental protocol: Harvest cells, block Fc receptors to prevent non-specific binding, stain with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface PRRs (e.g., anti-TLR2, anti-TLR4), fix cells if performing intracellular staining, acquire data on a flow cytometer, and analyze using software such as FlowJo to determine expression levels across cell populations.

Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence: Allows spatial localization of PRRs within tissues and correlation with pathological features in clinical specimens or disease models [13]. This technique preserves architectural context that is lost in dissociated cell analyses. Experimental protocol: Prepare tissue sections (4-6μm), perform antigen retrieval if required, block endogenous peroxidases and non-specific binding, incubate with primary antibodies against PRRs, followed by enzyme-conjugated or fluorescent secondary antibodies, develop with chromogenic substrates (DAB for IHC) or mounting media with DAPI (for IF), and visualize by light or fluorescence microscopy.

PRR Functional Assays

Determining the functional consequences of PRR activation requires specialized assays that measure downstream signaling events and biological responses:

Luciferase Reporter Assays: Quantify activation of specific transcription factors (NF-κB, IRF3, AP-1) following PRR stimulation [13]. These assays provide sensitive, quantitative readouts of pathway-specific PRR signaling. Experimental protocol: Plate cells in 24-well or 48-well plates, co-transfect with PRR expression plasmids and reporter constructs (e.g., NF-κB-luc, IFN-β-luc), stimulate with specific PRR ligands (e.g., LPS for TLR4, poly(I:C) for TLR3), lyse cells after 6-24 hours, measure luciferase activity using a luminometer, and normalize data to co-transfected control reporters (e.g., Renilla luciferase).

Cytokine/Chemokine Measurement: Evaluate functional outputs of PRR activation by quantifying secretion of inflammatory mediators using ELISA, multiplex bead arrays, or MSD assays [13]. These measurements correlate PRR signaling with biologically relevant immune responses. Experimental protocol: Stimulate PRR-expressing cells with specific ligands (PAMPs or DAMPs), collect culture supernatants at various time points (typically 6-48 hours), quantify cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-α/β) using commercial ELISA kits or multiplex arrays according to manufacturer protocols, and generate standard curves for absolute quantification.

Knockdown/Knockout Approaches: Determine PRR-specific functions using genetic disruption techniques including siRNA, shRNA, CRISPR/Cas9, or genetic deletion in animal models [13]. These loss-of-function experiments establish necessity for specific PRRs in immune responses. Experimental protocol: Design and synthesize targeting sequences for specific PRRs, deliver using appropriate transfection/transduction methods (lipofection, electroporation, viral vectors), confirm knockdown/knockout efficiency by qRT-PCR or Western blot, stimulate cells with relevant ligands, and measure downstream responses compared to control cells.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PRR Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR Agonists | Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2) | Bacterial lipopeptide simulation | Activates TLR1/2 heterodimers |

| Poly(I:C) (TLR3) | Viral dsRNA mimic | Binds and activates TLR3 | |

| LPS (TLR4) | Gram-negative bacterial infection models | Activates TLR4/MD-2 complex | |

| Imiquimod (TLR7) | Antiviral response studies | Activates endosomal TLR7 | |

| CpG ODN (TLR9) | Bacterial DNA recognition | Binds and activates TLR9 | |

| NLR Agonists | MDP (NOD2) | Bacterial peptidoglycan response | Activates NOD2 signaling |

| iE-DAP (NOD1) | Gram-negative bacterial sensing | Specific NOD1 ligand | |

| Nigericin (NLRP3) | Inflammasome activation | Potassium ionophore activating NLRP3 | |

| RLR Agonists | 5'ppp-RNA (RIG-I) | Viral RNA recognition studies | Specific RIG-I ligand |

| Poly(I:C) (MDA5) | Long dsRNA viral infection mimic | Activates MDA5 signaling | |

| Inhibitors | TAK-242 (TLR4) | TLR4 signaling blockade | Inhibits TLR4-TIR domain interactions |

| BX795 (TBK1/IKKε) | IRF3 pathway inhibition | Blocks TBK1/IKKε kinase activity | |

| MCC950 (NLRP3) | Inflammasome inhibition | Specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor | |

| Antibodies | Anti-TLR4 | Receptor expression/blocking | Detects or blocks TLR4 |

| Anti-phospho-IRF3 | Signaling activation readout | Detects activated IRF3 | |

| Anti-NLRP3 | Inflammasome formation studies | Detects NLRP3 expression |

Pathogen Evasion Strategies and PRR Regulation

Microbial Evasion of PRR Recognition

Successful pathogens have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade or subvert PRR-mediated detection, representing a dynamic evolutionary arms race between host immunity and microbial survival strategies [13]. These evasion tactics include:

Structural Modification of PAMPs: Many pathogens alter their molecular patterns to avoid PRR recognition. For example, some bacteria modify their lipid A moiety of LPS to reduce TLR4 activation, while certain viruses cap their RNA or mask 5'-triphosphates to avoid RIG-I detection [13].

Sequestration of PAMPs: Pathogens may physically hide their immunostimulatory molecules from PRR surveillance. Some intracellular bacteria and viruses assemble within membrane-bound compartments that limit exposure to cytoplasmic PRRs, while others export PAMPs to cellular locations devoid of appropriate sensors [13].

Expression of PRR Inhibitors: Numerous pathogens encode proteins that directly interfere with PRR signaling cascades. Viral proteins may target key signaling adaptors (MAVS, MyD88, TRIF) for degradation, while bacterial effectors can inhibit critical kinases (TBK1, IKK) or cleave signaling components to disrupt communication pathways [13].

Modulation of Host Epigenetic Regulation: Certain pathogens manipulate host epigenetic machinery to suppress PRR expression or function. This includes inducing repressive histone modifications at PRR gene promoters or driving DNA methylation that silences critical components of immune signaling pathways [13].

SARS-CoV-2 exemplifies sophisticated PRR evasion through multiple mechanisms, including masking its RNA to avoid RIG-I/MDA5 detection, encoding proteins that degrade PRR signaling components, and disrupting IFN signaling pathways [13]. These evasion strategies contribute to the delayed interferon response observed in severe COVID-19 cases, allowing rapid viral replication before immune containment [13].

Endogenous Regulation of PRR Activity

To prevent excessive or inappropriate inflammation, PRR signaling is subject to multiple layers of endogenous regulation that fine-tune immune responses:

Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Control: PRR expression and function are regulated through transcription factor networks, microRNAs, and RNA-binding proteins that adjust receptor levels in response to cellular conditions [9]. Negative feedback mechanisms induced by PRR signaling itself help terminate responses once threats are eliminated.

Post-translational Modifications: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteolytic cleavage dynamically regulate PRR activity, subcellular localization, and interactions with signaling partners [9]. Both activating and inhibitory modifications create molecular switches that control signal initiation and duration.

Compartmentalization and Trafficking: Strategic localization within specific cellular compartments (plasma membrane, endosomes, mitochondria) controls PRR access to ligands and signaling components [9]. Regulated trafficking between compartments provides an additional control layer for PRR activity.

Inhibitory PRRs (iPRRs): A specialized class of receptors including CD300a/f, Siglecs, CEACAM1, LILRB1, and LAIR-1 recognizes endogenous or microbial patterns associated with homeostasis or modified self, delivering inhibitory signals that counterbalance activating PRRs [9]. These iPRRs provide contextual information to prevent excessive inflammation against non-threatening stimuli.

Metabolic and Microbial Regulation: Cellular metabolic states and the commensal microbiome significantly influence PRR responses through metabolite production, cross-talk with other signaling pathways, and tonic stimulation that sets activation thresholds [9].

This sophisticated regulatory network ensures that PRR-mediated immunity remains appropriately scaled to threats, minimizing collateral tissue damage while maintaining effective pathogen defense. Dysregulation of these control mechanisms contributes to inflammatory diseases, autoimmunity, and cancer pathogenesis [9].

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Targeting

PRRs in Disease Pathogenesis

PRRs play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of diverse human diseases, making them attractive therapeutic targets:

Infectious Diseases: PRR function directly impacts susceptibility to and outcomes of infectious diseases. Genetic polymorphisms in PRRs (TLR3, TLR7, RIG-I) are associated with increased severity of COVID-19, while deficiencies in NLRs or TLRs predispose to specific bacterial and fungal infections [13]. The magnitude and timing of PRR activation critically determine whether protective immunity or pathological inflammation develops during infections.

Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Disorders: Excessive or inappropriate PRR activation contributes to autoimmune pathology. In systemic lupus erythematosus, defective clearance of cellular debris leads to persistent DAMP exposure and TLR7/TLR9 activation, driving anti-nuclear antibody production [9]. NLRP3 inflammasome overactivation underlies several autoinflammatory syndromes like cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) [9].

Cancer: PRRs demonstrate dual roles in oncogenesis and cancer control. Chronic inflammation driven by PRR signaling can promote tumor development, while PRR activation in tumor cells or immune cells can stimulate antitumor immunity [11] [9]. "Viral mimicry"—the transcriptional reactivation of endogenous retroelements—in cancer cells can trigger RLR and MDA5 sensing, inducing interferon responses that enhance antitumor immunity [14] [15].

Long COVID: Altered PRR expression and signaling persistence may contribute to long COVID pathogenesis. Changes in TLRs, cGAS, and STING expression have been detected in long COVID patients, suggesting sustained innate immune activation drives persistent symptoms [13].

Therapeutic Targeting of PRRs

The strategic position of PRRs at the immunity interface makes them promising targets for therapeutic intervention:

PRR Agonists as Vaccine Adjuvants: PRR ligands effectively enhance vaccine immunogenicity by activating innate immunity and promoting adaptive responses [16]. Multiple TLR agonists are incorporated into licensed vaccines: MPLA (TLR4 agonist) in AS04-adjuvanted vaccines (Hepatitis B, HPV), CpG 1018 (TLR9 agonist) in Heplisav-B, and AS01 (containing MPL and saponin) in Shingrix [16]. Combination of multiple PRR agonists may provide synergistic benefits through complementary pathway activation [16].

PRR Agonists in Cancer Immunotherapy: PRR activation can overcome immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment and stimulate antitumor immunity [11]. Intratumoral injection of PRR agonists (TLR agonists, STING agonists) is being explored to convert "cold" tumors into "hot," T-cell-inflamed tumors responsive to checkpoint inhibitors [11] [9].

PRR Antagonists in Inflammatory Diseases: Inhibiting excessive PRR signaling may benefit autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. TLR7/TLR9 antagonists are investigated for lupus, while NLRP3 inhibitors (MCC950) show promise in inflammatory diseases [9]. STING antagonists are being developed to ameliorate type I interferonopathies [9].

Personalized Approaches: Understanding how PRR polymorphisms affect disease susceptibility and treatment responses will enable personalized immunotherapeutic strategies tailored to individual genetic backgrounds and disease characteristics [13] [9].

The continuing elucidation of PRR biology, ligand recognition mechanisms, signaling networks, and regulatory principles promises to unlock new therapeutic opportunities for infectious diseases, cancer, inflammatory disorders, and immune-mediated conditions. As the central sentinels of cellular immunity, PRRs remain compelling targets for manipulating immune responses in human health and disease.

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are conserved molecular structures essential for microbial survival that are recognized by the host innate immune system through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This recognition initiates inflammatory signaling pathways that constitute the first line of defense against invading pathogens [17] [3]. The conceptual framework of PAMPs and PRRs, first proposed by Charles Janeway in 1989, has fundamentally shaped our understanding of innate immunity and its role in activating adaptive immune responses [17] [9] [3]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of four major PAMP classes: lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagellin, peptidoglycan, and microbial nucleic acids, with particular focus on their structures, recognition mechanisms, and associated signaling pathways relevant to inflammation initiation research and therapeutic development.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

Structure and Function

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin, is an amphipathic glycolipid that constitutes the major component of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria [17] [18]. LPS maintains membrane integrity, provides a permeability barrier against environmental toxins and antimicrobial compounds, and is essential for bacterial fitness in most Gram-negative species [17]. Structurally, LPS consists of three domains: the hydrophobic lipid A region embedded in the outer membrane, a core oligosaccharide, and a distal O-antigen polysaccharide chain [18]. The lipid A moiety, which contains phosphorylated glucosamine disaccharides with multiple acyl chains, is the conserved PAMP responsible for the immunostimulatory activity of LPS [17] [19].

Recognition Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Mammalian systems have evolved a sophisticated multi-protein complex for detecting LPS with exceptional sensitivity, capable of responding to picomolar concentrations [19]. The extracellular recognition process involves a sequential protein cascade:

- LPS-binding protein (LBP), a serum glycoprotein, initially binds to LPS aggregates and facilitates the extraction of LPS monomers [17] [18] [19].

- Monomeric LPS is transferred to cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), which exists in both membrane-bound (GPI-anchored) and soluble forms [17] [18].

- CD14 presents LPS to the MD-2/TLR4 complex. MD-2, which is stably associated with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), is the essential coreceptor that directly binds the lipid A moiety of LPS [18] [19].

- LPS binding induces dimerization of the TLR4-MD-2 complex, forming a symmetric `m'-shaped heterotetramer (2:2:2 complex of LPS:MD-2:TLR4) that initiates intracellular signaling [18] [19].

This receptor assembly triggers two distinct intracellular signaling cascades:

- MyD88-Dependent Pathway: Initiated at the plasma membrane, this pathway recruits the adaptor protein MyD88, leading to the activation of IRAK and TRAF6, ultimately activating NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors. This results in the rapid production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [18].

- TRIF-Dependent Pathway (MyD88-Independent): Initiated after endocytosis of the TLR4 complex, this pathway utilizes the adaptor TRIF to activate TBK1 and IKKε, leading to phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3. This induces the production of Type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) [18].

In addition to the cell surface TLR4 pathway, cytosolic LPS can be detected by inflammatory caspases (caspase-4/5 in humans, caspase-11 in mice). This intracellular sensing triggers pyroptosis, an inflammatory form of cell death, and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to process and release mature IL-1β [17].

Table 1: Key Proteins in LPS Recognition and Signaling

| Protein | Structure | Function in LPS Response |

|---|---|---|

| LBP | 58-60 kDa glycoprotein, N-terminal cationic residue cluster for LPS binding [18]. | Binds LPS aggregates, facilitates monomer extraction and transfer to CD14 [18] [19]. |

| CD14 | Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) glycoprotein, GPI-anchored or soluble [18]. | Recognizes LBP-delivered LPS, presents it to the TLR4-MD-2 complex [18]. |

| MD-2 | ~18 kDa protein, member of ML lipid-binding family [18] [19]. | Coreceptor for TLR4; directly binds lipid A; essential for TLR4 response to LPS [18] [19]. |

| TLR4 | Type I transmembrane protein with LRR extracellular domain and TIR intracellular domain [18]. | Pattern recognition receptor; forms complex with MD-2 and LPS; initiates intracellular signaling [17] [18]. |

| MyD88 | Adaptor protein with TIR and Death domains [18] [3]. | Primary TIR-domain adaptor for most TLRs; activates NF-κB and MAPK for pro-inflammatory cytokine production [18] [3]. |

Figure 1: LPS Recognition and Signaling Pathways. LPS is sequentially transferred by LBP and CD14 to the TLR4/MD-2 complex, triggering both MyD88-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokine production and TRIF-dependent type I interferon production.

Experimental Protocols for LPS Research

Protocol 1: Assessing TLR4 Activation via NF-κB Reporter Assay

- Cell Model: HEK293 cells stably expressing TLR4, MD-2, and CD14, transfected with an NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid.

- Stimulation: Treat cells with purified LPS (e.g., from E. coli O111:B4) across a concentration range (0.1-100 ng/mL) for 6-24 hours.

- Control: Include cells treated with lipid IVa (TLR4 antagonist) or LPS from Rhodobacter sphaeroides to confirm specificity [19].

- Readout: Measure luciferase activity. Validate cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-8) via ELISA [18].

Protocol 2: Detecting Cytosolic LPS-Induced Pyroptosis

- Cell Model: Primary murine bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) or human monocytic cell lines (THP-1).

- Transfection: Transfect cells with ultrapure LPS (1 µg/mL) using a transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine 2000) to deliver LPS into the cytosol.

- Inhibition: Pre-treat with caspase-4/11 inhibitor (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) [17].

- Readout: Measure cell viability (MTT assay) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release to quantify pyroptosis. Analyze IL-1β in supernatant via ELISA [17].

Flagellin

Structure and Function

Flagellin is the primary structural protein subunit of the bacterial flagellum, a whip-like appendage that enables bacterial motility [20]. As a PAMP, flagellin is recognized by the immune system at sub-nanomolar concentrations [20]. The protein is characterized by a highly conserved D1 domain at the N- and C-termini, which is essential for its recognition by PRRs, and a central hypervariable D3 domain that is dispensable for immune activation [20].

Recognition Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Flagellin is detected by immune cells via two primary mechanisms:

Extracellular Sensing by TLR5: Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) is a membrane-bound PRR that recognizes the conserved D1 domain of extracellular flagellin [20]. Upon binding, TLR5 dimerizes and recruits the adaptor protein MyD88, leading to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways. This results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [20]. In intestinal epithelial cells, TLR5 is exclusively expressed on the basolateral surface, providing a molecular basis for the polarity of the innate immune response. Pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella can translocate flagellin across the epithelium to the basolateral side, thereby triggering inflammation, whereas commensal bacteria primarily present flagellin at the apical surface, which does not initiate a response [21].

Cytosolic Sensing by the NLRC4 Inflammasome: When flagellin is delivered into the host cell cytoplasm by bacterial type III secretion systems (T3SS), it is recognized by members of the NLR family apoptosis inhibitory proteins (NAIPs). In mice, NAIP5 and NAIP6 bind directly to flagellin [20]. This flagellin-NAIP complex then recruits and activates NLRC4, leading to the assembly of a multi-protein complex called the inflammasome. The inflammasome activates caspase-1, which cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms and triggers pyroptosis [20].

Table 2: Flagellin Receptors and Their Functions

| Receptor | Location | Ligand Specificity | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR5 | Plasma Membrane (Basolateral in gut epithelium) | Conserved D1 domain of flagellin [20] [21] | MyD88-dependent activation of NF-κB/MAPK; induces proinflammatory gene expression [20]. |

| NAIP/ NLRC4 | Cytosol | C-terminal 35 amino acids of flagellin (in mice, via NAIP5/6) [20] | Forms inflammasome complex; activates caspase-1; processes and releases IL-1β and IL-18; induces pyroptosis [20]. |

Figure 2: Flagellin Sensing Pathways. Extracellular flagellin is sensed by TLR5, triggering a MyD88-dependent cytokine response. Cytosolic flagellin, often injected via a Type 3 Secretion System (T3SS), is detected by NAIPs, which activate the NLRC4 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation and pyroptosis.

Experimental Protocols for Flagellin Research

Protocol 1: Evaluating TLR5-Specific Signaling

- Cell Model: HEK293 cells transiently transfected with human TLR5 and an NF-κB-luciferase reporter.

- Stimulation: Treat with purified flagellin (e.g., from Salmonella typhimurium, 10-100 ng/mL) for 6-18 hours.

- Control: Use a recombinant flagellin protein lacking the hypervariable D3 domain (contains only D1/D2 domains) to confirm that immune stimulation is retained [20].

- Readout: Measure luciferase activity and quantify IL-8 secretion via ELISA.

Protocol 2: Assessing NAIP/NLRC4 Inflammasome Activation

- Cell Model: Primary BMDMs from C57BL/6 mice (which express functional NAIP5) or human macrophage models.

- Infection/Transfection: Infect with flagellated, T3SS-competent Salmonella (e.g., S. Typhimurium SL1344) at an MOI of 10:1, OR transfect with purified flagellin (0.5-1 µg/mL) using a transfection reagent.

- Inhibition: Pre-treat with caspase-1 inhibitor (YVAD) or NLRC4-specific siRNA [20].

- Readout: Measure LDH release for pyroptosis. Analyze culture supernatants for mature IL-1β by western blot and ELISA.

Peptidoglycan

Structure and Function

Peptidoglycan (also known as murein) is a vast, mesh-like macromolecule that forms a protective layer (sacculus) surrounding the cytoplasmic membrane of most bacteria [22] [23]. Its primary function is to provide structural strength and counteract the intracellular osmotic pressure, thereby preventing cell lysis [22]. The peptidoglycan polymer consists of glycan chains of alternating N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) residues, connected by β-(1,4)-glycosidic bonds [22] [23]. A short peptide stem (usually 4-5 amino acids) is attached to each NAM residue. Adjacent peptide stems are cross-linked, often by D-glutamic acid and D-alanine residues, creating a robust, 3-dimensional network that defines cell shape [22] [23]. The peptidoglycan layer is substantially thicker in Gram-positive bacteria (20-80 nm) than in Gram-negative bacteria (7-8 nm) [23].

Recognition Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The innate immune system recognizes peptidoglycan through both extracellular and cytosolic PRRs:

Extracellular Recognition: Peptidoglycan fragments can be recognized by several transmembrane receptors, including Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), often in heterodimeric complexes with TLR1 or TLR6, and certain C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) [3]. TLR2 recognition leads to the activation of NF-κB and the production of inflammatory cytokines.

Cytosolic Recognition: The primary cytosolic sensors for peptidoglycan are NOD-like receptors (NLRs), specifically NOD1 and NOD2 [3]. NOD1 recognizes meso-diaminopimelic acid (meso-DAP)-containing peptides derived primarily from Gram-negative bacteria, while NOD2 senses muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a motif found in peptidoglycan from both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [3]. Upon ligand binding in the cytosol, NOD1 and NOD2 oligomerize and recruit the adaptor protein RIPK2 (also known as RICK), which leads to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, promoting inflammatory gene expression [3].

Table 3: Peptidoglycan Structure and Recognition

| Feature | Description | Immunological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar Backbone | Alternating N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) with β-(1,4) linkages [22] [23]. | Target for lysozyme, a host enzyme that cleaves these bonds and acts as an antimicrobial agent [23]. |

| Peptide Stem | 4-5 amino acid chain attached to NAM; composition varies by species (e.g., contains D-amino acids) [22] [23]. | Source of unique molecular patterns (e.g., D-amino acids) not found in host proteins, enabling self/non-self discrimination. |

| Cross-links | Connect peptide stems from adjacent glycans; mediated by enzymes like DD-transpeptidases (penicillin-binding proteins) [22] [23]. | Targeted by beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g., penicillin), which inhibit the cross-linking enzymes [22]. |

| Primary Sensors | TLR2 (extracellular), NOD1/NOD2 (cytosolic) [3]. | Initiate pro-inflammatory signaling; NOD2 mutations are linked to Crohn's disease, highlighting its role in gut immunity [3]. |

Microbial Nucleic Acids

Microbial nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) constitute a major class of PAMPs distinguished from host nucleic acids by their structure, modification status, and subcellular localization during infection [24]. The innate immune system has evolved numerous PRRs to detect these molecules in various compartments, including endosomes and the cytosol.

- Bacterial DNA: Characterized by unmethylated CpG dinucleotides within specific sequence contexts (CpG motifs), which are underrepresented and methylated in vertebrate DNA [24] [3].

- Viral RNA: Features include 5'-triphosphate groups on single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) generated during replication, and specific secondary structures [24].

- Viral/Bacterial DNA: Can be sensed in the cytosol, particularly when in a double-stranded (dsDNA) form [24].

Recognition Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Endosomal Recognition

- TLR9 is the primary sensor for unmethylated CpG DNA within endosomes. It signals through MyD88 to activate NF-κB and IRF7, inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons [24] [3].

- TLR3 binds to viral or synthetic dsRNA in endosomes. It signals via the adaptor TRIF (MyD88-independent pathway), leading to the activation of IRF3 and NF-κB, and the production of type I interferons and cytokines [24] [3].

- TLR7 (in humans) and TLR8 recognize viral ssRNA in endosomes, signaling through MyD88 to activate NF-κB and IRF7 [24].

Cytosolic Recognition

- RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs): This family includes RIG-I and MDA5. RIG-I recognizes short dsRNA with a 5'-triphosphate, while MDA5 senses long dsRNA. Both signal through the mitochondrial adaptor MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein), leading to the activation of IRF3, IRF7, and NF-κB, and the potent induction of type I interferons [24] [3].

- cGAS (Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase): This is the primary sensor for cytosolic dsDNA. Upon binding DNA, cGAS synthesizes the second messenger 2'3'-cGAMP. cGAMP then binds to the adaptor protein STING on the endoplasmic reticulum, which activates TBK1 and IRF3, resulting in a robust type I interferon response [24] [3].

- AIM2-like Receptors (ALRs): AIM2 forms an inflammasome in response to cytosolic dsDNA by recruiting ASC and caspase-1, leading to the maturation of IL-1β/IL-18 and pyroptosis [9] [3].

- NOD2: In addition to sensing peptidoglycan, NOD2 can also function as a cytosolic sensor of viral ssRNA, activating NF-κB and IRF3 to induce type I interferons [24].

Table 4: Nucleic Acid Sensing PRRs and Their Ligands

| Receptor | Location | Ligand | Key Adaptor | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR9 | Endosome | Unmethylated CpG DNA [24] [3] | MyD88 | Type I IFN, Pro-inflammatory Cytokines [24] [3] |

| TLR3 | Endosome | Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) [24] [3] | TRIF | Type I IFN [24] [3] |

| TLR7/8 | Endosome | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) [24] [3] | MyD88 | Type I IFN, Pro-inflammatory Cytokines [24] [3] |

| RIG-I | Cytosol | Short dsRNA with 5' triphosphate [24] | MAVS | Type I IFN [24] |

| MDA5 | Cytosol | Long dsRNA [24] | MAVS | Type I IFN [24] |

| cGAS | Cytosol | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [24] [3] | STING | Type I IFN [24] [3] |

| AIM2 | Cytosol | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [24] [3] | ASC (Inflammasome) | Caspase-1 activation, IL-1β, Pyroptosis [24] [3] |

Figure 3: Nucleic Acid Sensing Pathways. Endosomal TLRs (3, 7/8, 9) detect nucleic acids after pathogen internalization. Cytosolic RNA is sensed by RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs) via MAVS, while cytosolic DNA is detected by cGAS-STING and AIM2 inflammasome pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Nucleic Acid Sensing

Protocol 1: Measuring cGAS-STING Pathway Activation

- Cell Model: Human monocytic THP-1 cells or primary human macrophages.

- Stimulation/Transfection: Transfert with synthetic dsDNA (e.g., ISD, 45BP DNA, 1 µg/mL) or interferon-stimulatory DNA (ISD) using a transfection reagent. Alternatively, infect with DNA viruses (e.g., HSV-1).

- Inhibition: Use cGAS- or STING-specific inhibitors (e.g., H-151, RU.521) or siRNA knockdown [24].

- Readout: Measure IFN-β mRNA by qRT-PCR and protein by ELISA. Analyze phosphorylation of IRF3 by western blot.

Protocol 2: Assessing RIG-I Activation

- Cell Model: A549 lung epithelial cells or primary fibroblasts.

- Stimulation/Transfection: Infect with Sendai virus or transfect with synthetic 5'-triphosphate RNA (3p-hpRNA, 1 µg/mL).

- Inhibition: Use RIG-I-specific inhibitor (e.g., RIG-I-N) or MAVS-deficient cells [24].

- Readout: Measure IFN-β and ISG (e.g., MX1) mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. Assess IRF3 phosphorylation by western blot.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for PAMP Signaling Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure LPS | Highly purified LPS with low protein/contaminant content, specific to bacterial serotypes. | Defining specific TLR4-MD-2 activation without confounding PRR engagement [18]. |

| Recombinant Flagellin (D1/D2 domains) | Purified flagellin protein containing the conserved TLR5-binding domains. | Studying TLR5-specific signaling in vitro and in vivo; used as a vaccine adjuvant [20]. |

| Muramyl Dipeptide (MDP) | Minimal bioactive peptidoglycan fragment recognized by NOD2. | Activating the NOD2 signaling pathway in cellular assays [3]. |

| CL-097 | Synthetic imidazoquinoline compound that acts as a TLR7 agonist. | Studying endosomal TLR7 signaling and type I interferon responses [3]. |

| Poly(I:C) | Synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). | A TLR3 and MDA5 agonist for mimicking viral infection and inducing interferon responses [24] [3]. |

| 2'3'-cGAMP | Native second messenger produced by cGAS upon DNA sensing. | Directly activating the STING pathway downstream of cGAS [24]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Cells | Isogenic cell lines with specific PRR or adaptor gene (e.g., MYD88, TRIF, MAVS) knocked out. | Defining the specific roles of signaling molecules in PAMP-induced pathways [17] [24]. |

| NF-κB/IRF Luciferase Reporter Cells | Stable cell lines with inducible promoters driving luciferase expression. | Quantifying activation of key transcription factors in response to PAMP stimulation [20] [18]. |

The detailed molecular understanding of PAMP recognition by their corresponding PRRs has profoundly advanced the field of immunology and provides a robust framework for therapeutic innovation. The structural insights into receptor-ligand interactions, such as the LPS-TLR4/MD-2 complex or the flagellin-TLR5 interface, reveal precise targets for drug discovery. The distinct signaling pathways activated—leading to cytokine production, interferon responses, or inflammasome activation—offer multiple avenues for intervention. Agents that modulate these pathways, either as antagonists to curb deleterious inflammation (e.g., in sepsis or autoimmune diseases) or as agonists to boost immune responses (e.g., in vaccines or cancer immunotherapy), represent a promising frontier in biomedical research. Continued investigation into the intricate regulation of PAMP-PRR interactions and their downstream signaling cascades is essential for developing the next generation of immunomodulatory therapies.

This technical guide delineates the fundamental signaling pathways activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), with a focused analysis of NF-κB signaling and inflammasome activation. These pathways represent the cornerstone of the innate immune response, orchestrating initial inflammatory responses to infection and injury. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise mechanisms—from receptor engagement to transcriptional regulation and protease activation—is paramount for developing targeted therapies for inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. This whitepaper integrates current mechanistic insights, experimental methodologies, and key reagent solutions to support advanced research in immunology and translational medicine.

The innate immune system serves as the first line of defense, employing a limited set of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect conserved molecular signatures. PAMPs, derived from microorganisms, and DAMPs, released from damaged or stressed host cells, are the primary ligands for these receptors [25] [7]. The engagement of PRRs triggers highly conserved signal transduction cascades that lead to the production of inflammatory mediators, the recruitment of immune cells, and the activation of adaptive immunity. Two of the most critical downstream signaling events are the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB and the assembly of inflammasome complexes, which are central to the pathogenesis of numerous chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. The interplay between PAMPs and DAMPs can fine-tune these responses, with their combined presence often leading to synergistic amplification of inflammation, a key consideration for therapeutic intervention [26] [7].

NF-κB Signal Transduction Pathway

NF-κB is a family of transcription factors that regulates a vast array of genes involved in inflammation, immunity, cell survival, and proliferation. It is a pivotal mediator of the response to both PAMPs and DAMPs [27] [28] [29].

Pathway Architecture and Key Components

The NF-κB family comprises five members: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50/p105), and NF-κB2 (p52/p100). These proteins share a conserved Rel homology domain (RHD) responsible for DNA binding and dimerization. NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory proteins, primarily the IκB family (e.g., IκBα), which mask their nuclear localization signals [30] [28] [29]. Activation occurs via two principal pathways:

- The Canonical NF-κB Pathway: This pathway is rapidly activated by a broad range of stimuli, including PAMPs (via TLRs, IL-1R), DAMPs, and cytokines like TNF-α. It primarily leads to the activation of p50:RelA and p50:c-Rel dimers [28] [29].

- The Non-Canonical NF-κB Pathway: This pathway is selectively activated by a subset of TNF receptor superfamily members (e.g., CD40, BAFFR, RANK). It involves the processing of p100 to p52, resulting in the nuclear translocation of p52:RelB dimers [29].

Table 1: Core Components of the NF-κB Signaling Pathways

| Component | Gene | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| RelA (p65) | RELA | Transcriptional activator | Contains transactivation domain; part of canonical pathway |

| p105/p50 | NFKB1 | DNA binding subunit | Processed from p105; lacks transactivation domain |

| p100/p52 | NFKB2 | DNA binding subunit | Processed from p100 in non-canonical pathway |

| RelB | RELB | Transcriptional activator | Primarily functions in non-canonical pathway |

| IκBα | NFKBIA | Inhibitory protein | Sequesters NF-κB in cytoplasm; primary target in canonical pathway |

| IKKα | CHUK | Kinase subunit | Critical for non-canonical pathway; also involved in canonical |

| IKKβ | IKBKB | Kinase subunit | Main catalytic driver of canonical pathway |

| NEMO (IKKγ) | IKBKG | Regulatory subunit | Essential scaffold for canonical IKK complex activation |

| NIK | MAP3K14 | Kinase | Central regulator of non-canonical pathway |

Mechanism of Canonical NF-κB Activation

The canonical pathway is a model of inducible, ubiquitin-dependent signal transduction. The process can be broken down into key steps, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Diagram 1: Canonical NF-κB Activation Pathway.

- Receptor Proximal Signaling: Ligation of receptors like TLR4 by LPS leads to the recruitment of adapter proteins (e.g., MyD88, TRIF), initiating a kinase cascade involving IRAKs and TRAF6. TRAF6 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, generating K63-linked ubiquitin chains that activate the kinase TAK1 [28] [29].

- IKK Complex Activation: TAK1 phosphorylates and activates the IKK complex (IKKα, IKKβ, NEMO). IKKβ is the critical kinase for the canonical pathway [29].

- IκBα Phosphorylation and Degradation: The activated IKK complex phosphorylates IκBα on two critical N-terminal serine residues. This phosphorylation tags IκBα for K48-linked ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [30] [28].

- NF-κB Translocation and Transcription: With IκBα degraded, the canonical NF-κB dimer (typically p50:RelA) is freed, exposes its nuclear localization signal, and translocates to the nucleus. There, it binds to κB enhancer elements and drives the expression of target genes, including those encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β), chemokines, adhesion molecules, and its own inhibitor, IκBα, which creates an auto-regulatory negative feedback loop [27] [28].

Mechanism of Non-Canonical NF-κB Activation

The non-canonical pathway is characterized by its reliance on the kinase NIK (NF-κB Inducing Kinase) and the processing of NF-κB2 p100 to p52.

Diagram 2: Non-Canonical NF-κB Activation Pathway.

- NIK Stabilization: In unstimulated cells, NIK is continuously bound and targeted for degradation by a complex containing TRAF3 and cIAP1/2. Engagement of receptors like CD40 or BAFFR leads to the degradation of TRAF3, allowing NIK to accumulate [29].

- p100 Phosphorylation and Processing: NIK, in concert with IKKα, phosphorylates the C-terminal region of p100. This phosphorylation event triggers the polyubiquitination and partial proteasomal degradation of p100, removing its IκB-like inhibitory domain and generating the mature p52 subunit [29].

- Nuclear Translocation: The processed p52:RelB dimer translocates to the nucleus to regulate genes involved in lymphoid organ development, B-cell maturation, and adaptive immunity [29].

Inflammasome Activation Pathway

Inflammasomes are multi-protein cytoplasmic complexes that serve as activation platforms for inflammatory caspases, primarily caspase-1. Their activation is a key mechanism for the maturation and secretion of the potent pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, and for the induction of a pro-inflammatory form of cell death called pyroptosis [27].

Inflammasome Assembly and Function

Inflammasomes are typically composed of a sensor protein (a PRR), the adapter protein ASC, and pro-caspase-1. Sensor proteins can be NLRs (e.g., NLRP3), ALRs (e.g., AIM2), or others.

Diagram 3: Canonical Inflammasome Activation (Two-Signal Model).

- Priming (Signal 1): This initial step is often provided by PAMPs (e.g., LPS via TLR4) or cytokines that activate NF-κB. This leads to the transcriptional upregulation of inflammasome components, including the sensor protein (e.g., NLRP3) and the inactive precursor cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 [27].

- Activation (Signal 2): A second, distinct signal triggers the assembly of the inflammasome complex. This signal can be provided by a wide range of DAMPs and PAMPs, including extracellular ATP (via P2X7 receptor inducing K+ efflux), crystalline structures (e.g., uric acid crystals, cholesterol crystals), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and microbial toxins [7].

- Caspase-1 Activation and Effector Functions: Upon sensing the activation signal, the sensor protein oligomerizes and recruits ASC, which then aggregates into a large filamentous structure ("speck") that recruits and activates pro-caspase-1 through proximity-induced autoproteolysis. Active caspase-1 then:

- Cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their biologically active forms.

- Cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD); the N-terminal fragment of GSDMD forms pores in the plasma membrane, leading to pyroptosis—a lytic cell death that releases inflammatory contents, including mature cytokines [7].

Experimental Protocols for Key Pathway Analysis

Protocol: Assessing Canonical NF-κB Activation by Immunoblotting

This protocol is a cornerstone for evaluating pathway activity in response to PAMPs like LPS.

Method:

- Cell Stimulation: Seed immortalized macrophages (e.g., RAW 264.7, THP-1 derived) in 6-well plates. Stimulate with a canonical NF-κB inducer (e.g., 100 ng/mL E. coli LPS) for time points ranging from 0 to 120 minutes.

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Centrifuge at 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to collect the supernatant (whole cell lysate). For nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation, use a commercial kit to separate fractions.