Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling of Inflammatory Cytokines: Mechanisms, Research Methods, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms governing inflammatory cytokine networks, essential knowledge for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling of Inflammatory Cytokines: Mechanisms, Research Methods, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms governing inflammatory cytokine networks, essential knowledge for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore fundamental biological principles, including distinct signaling pathways and their roles in physiological and pathological processes from immune regulation to cancer. The content covers advanced methodological approaches for studying these complex signaling loops, addresses common research challenges and optimization strategies, and provides frameworks for validating findings and comparing therapeutic interventions. By synthesizing current research and emerging technologies, this review aims to equip professionals with the insights needed to advance both fundamental understanding and clinical translation in this critical field.

Core Principles and Biological Significance of Inflammatory Cytokine Signaling

Defining Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling Mechanisms

Cell-to-cell communication is a cornerstone of multicellular life, enabling the coordination of complex physiological processes. Within this framework, autocrine and paracrine signaling represent two fundamental mechanisms for local cellular communication. Autocrine signaling occurs when a cell secretes a signaling molecule that binds to receptors on its own surface, thereby influencing its own behavior. In contrast, paracrine signaling involves a cell secreting molecules that act on nearby, distinct cells [1]. These signaling modes are particularly crucial for the function of inflammatory cytokines, which coordinate immune responses through complex local signaling networks [2] [3]. Understanding the precise mechanisms distinguishing these signaling types is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to target specific pathways in diseases ranging from autoimmune disorders to cancer.

Core Definitions and Functional Distinctions

Fundamental Signaling Concepts

The classification of chemical signaling in multicellular organisms is primarily based on the distance the signal travels and the relationship between the signaling and target cells:

Autocrine Signaling: A cell produces and secretes a signaling molecule that then binds to receptors on its own membrane. This self-stimulation creates a feedback loop that can amplify responses, maintain cell states, or coordinate group behavior when multiple identical cells respond similarly [1]. Examples include pain regulation, inflammatory responses, and early developmental processes [1].

Paracrine Signaling: A cell releases signaling molecules into the extracellular fluid that act on nearby, distinct cells. These signals typically elicit rapid responses that are spatially and temporally localized, as the ligands are quickly degraded or removed from the extracellular space [1]. A classic example is synaptic transmission between nerve cells [1].

Endocrine Signaling: For comparative context, endocrine signaling involves hormones released into the bloodstream by specialized glands, affecting distant target cells throughout the body [1].

Comparative Analysis of Signaling Modes

Table 1: Characteristic comparison of autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms

| Characteristic | Autocrine Signaling | Paracrine Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Range | Same cell or cells of identical type | Neighboring cells (short distances) |

| Temporal Dynamics | Can sustain prolonged cellular states | Typically rapid, transient responses |

| Signal Degradation | May be internalized or degraded after binding | Quickly degraded by enzymes or removed by neighboring cells |

| Primary Functions | Cellular self-maintenance, fate stabilization, population coordination | Local tissue coordination, rapid defensive responses |

| Example Contexts | Inflammatory pain regulation, viral response, development [1] | Synaptic transmission, immune cell recruitment [1] |

Quantitative Analysis of Signaling Parameters

Concentration and Temporal Dynamics

The functional differences between autocrine and paracrine signaling are reflected in their quantitative parameters:

Table 2: Quantitative parameters in cytokine signaling

| Parameter | Autocrine Signaling | Paracrine Signaling | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Concentration | Can achieve high local concentration at producing cell membrane | Graded concentration decreasing with distance from source | Computational models show steep concentration gradients [4] |

| Response Time | Immediate initiation following production | Diffusion-dependent delay to target cells | Microcavity platforms demonstrate temporal delays [4] |

| Signaling Duration | Can be self-sustaining through positive feedback | Typically transient due to rapid degradation | TNF production shows sustained vs. transient patterns [3] |

| Cellular ECâ‚…â‚€ | Often lower due to preferential access to self-receptors | Higher concentrations needed for distant cell activation | Isolated VPC studies show differential dose responses [5] |

The concentration dynamics fundamentally differ between these signaling modes. In autocrine signaling, the producing cell experiences the highest effective concentration, potentially creating robust self-stimulation. In paracrine signaling, concentrations form spatial gradients, creating positional information across a field of cells [4]. These quantitative differences have profound implications for network behaviors, as demonstrated in studies of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production where the same cytokine can function through autocrine loops in some contexts (CpG DNA stimulation) while acting primarily through paracrine mechanisms in others (LPS stimulation) [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Discrimination

Microcavity Platform for Signal Isolation

Objective: To distinguish autocrine from paracrine signals in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) culture by physically constraining cell distributions.

Methodology Details:

- Microcavity Fabrication: Create arrayed microwells using poly(dimethyl siloxane) silicone (PDMS) or poly(ethylene oxide) (sPEG) hydrogels with precisely controlled diameters (15μm for single-cell confinement, 40μm for multi-cell clusters) [4].

- Surface Functionalization: Covalently link extracellular matrix components (fibronectin) or signaling molecules (heparin for cytokine presentation) to cavity surfaces [4].

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at low density to achieve either single cells per microcavity (autocrine-dominated) or small cell clusters (paracrine-enabled) [4].

- Factor Analysis: Collect conditioned media and perform multiplex immunoassays for candidate factors, followed by partial least squares (PLS) analysis to correlate spatial configuration with secreted factors and cell fate outcomes [4].

Key Applications: This platform successfully identified autocrine VEGF and TGF-β loops in HSC self-renewal and demonstrated that autocrine signals predominantly maintain quiescence in single-cell niches, while paracrine signals drive proliferation in multi-cell environments [4].

Computational Modeling of Network Dynamics

Objective: To determine how autocrine loops contribute to cell fate patterning in C. elegans vulva development.

Methodology Details:

- Network Modeling: Construct ordinary differential equation-based models incorporating known interactions between EGF-Ras-MAPK and Delta-Notch pathways, including potential autocrine loops through secreted Delta ligands [5].

- Parameter Variation: Perform Monte Carlo sampling across parameter space (affinity constants, Hill coefficients, production/degradation rates) to identify parameter sets that reproduce wild-type cell fate patterns [5].

- Experimental Validation: Test model predictions using isolated vulva precursor cells (VPCs) exposed to varying EGF concentrations, assessing fate specification in the absence of neighboring cells (eliminating paracrine signals) [5].

Key Findings: The model revealed that 1.9% of wild-type parameter solutions could stabilize 2° cell fate in isolated VPCs through a DSL-Notch autocrine loop, characterized by high secreted Delta expression and specific network dynamics [5]. This demonstrated how quantitative variation in the same network can produce qualitatively distinct patterning modes.

Signaling Visualization

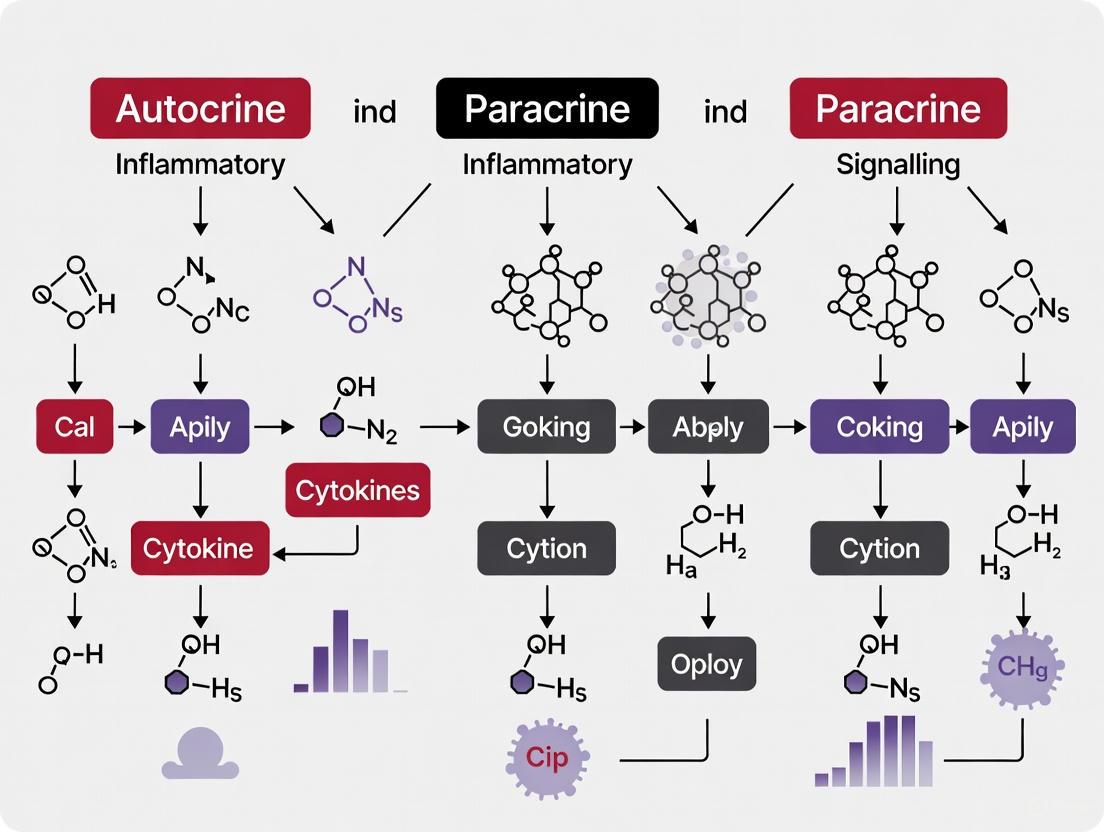

Cytokine Signaling Pathways Diagram

Research Reagent Solutions for Signaling Studies

Table 3: Essential research reagents for autocrine/paracrine signaling studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microfabrication Materials | PDMS, sPEG-hydrogels, Heparin-functionalized matrices | Spatial constraint of cell signaling [4] | Creates defined microenvironments to physically separate autocrine vs. paracrine contexts |

| Pathway Inhibitors | TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitors (Galunisertib), JAK/STAT inhibitors (Tofacitinib) | Blocking specific paracrine pathways [6] | Inhibits receptor activation to dissect pathway contributions to observed phenotypes |

| Cytokine Neutralizing Antibodies | Anti-IL-6, Anti-TGF-β, Anti-TNF-α | Selective blockade of extracellular signaling molecules [3] [6] | Distinguishes functions of specific cytokines in complex mixtures; confirms paracrine actions |

| Recombinant Ligands | EGF, SCF, TPO, FLT3L, purified cytokines | Controlled stimulation studies [4] [5] | Provides defined signals at specific concentrations to measure cellular responses |

| Detection Systems | Multiplex immunoassays, Phospho-specific flow cytometry, GFP-reporters | Quantifying pathway activation and secretion [3] [4] | Measures dynamic changes in signaling activity and secreted factors with high sensitivity |

Implications for Inflammatory Cytokine Research

The distinction between autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms has profound implications for understanding inflammatory processes and developing targeted therapies. In cancer biology, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) extensively utilize paracrine signaling to establish immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments. Specific CAF subtypes secrete distinct paracrine factors: myCAFs produce TGF-β to suppress T-cell activation and promote regulatory T-cell differentiation, while iCAFs secrete IL-6 and CXCL12 to recruit additional immunosuppressive cells [6]. These paracrine networks create physical and biochemical barriers that limit effective immune responses and contribute to therapy resistance.

The dynamic allostery mechanism recently identified in TGF-β signaling exemplifies the sophisticated regulation of autocrine/paracrine decisions. The conformational entropy redistribution (CER) in the L-TGF-β1-GARP-avβ8 complex enables context-dependent signaling - either promoting autocrine signaling while TGF-β remains latent or allowing release for paracrine actions [7]. This structural insight reveals how the same cytokine can mediate distinct biological outcomes through different signaling modes, potentially explaining the paradoxical roles of TGF-β in both inhibiting and promoting cancer progression.

From a therapeutic perspective, targeting autocrine versus paracrine signaling requires distinct strategic approaches. Autocrine loops may be interrupted by receptor antagonists or intracellular pathway inhibitors, while paracrine signaling might be blocked by neutralizing antibodies or trap receptors. The emerging understanding that the same network can be quantitatively tuned to utilize different signaling modes [5] suggests that therapeutic strategies may need to account for potential plasticity in signaling mechanisms across physiological contexts and disease states.

Key Inflammatory Cytokines and Their Receptor Systems

Inflammatory cytokines are signaling proteins that play a pivotal role in coordinating the immune system's response to infection, injury, and other threats [8] [2]. These molecules are predominantly secreted by immune cells such as helper T cells (Th) and macrophages, and promote inflammation, a fundamental component of the host defence mechanism [8]. The precise interplay between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines determines the net inflammatory outcome, and dysregulation of this balance is implicated in a wide array of diseases, including atherosclerosis, cancer, and autoimmune disorders [8] [9]. Understanding the specific receptor systems these cytokines engage is crucial for deciphering their biological functions and for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. This guide frames the complex landscape of key inflammatory cytokines within the context of autocrine and paracrine signaling, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed technical resource.

Key Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Their Functions

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are instrumental in initiating and amplifying the inflammatory response. The following table summarizes the core set of these cytokines, their primary cellular sources, and their major functions.

Table 1: Key Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Functions

| Cytokine | Main Cellular Sources | Major Functions |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β [10] [9] | Macrophages, Monocytes, Fibroblasts, Endothelial Cells [10] [9] | Acts as an endogenous pyrogen; stimulates CD4+ T cell differentiation into Th17 cells; induces hyperalgesia; upregulates endothelial adhesion molecules [10] [9]. |

| TNF-α [10] [9] | Macrophages, T Cells [10] | Key mediator in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia; triggers expression of vascular endothelial adhesion molecules; promotes immune cell infiltration; can induce shock and tissue destruction [8] [10] [9]. |

| IL-6 [10] | Monocytes, Fibroblasts, Endothelial Cells, T & B Cells, Macrophages [10] | Pleiotropic cytokine; induces B-cell differentiation into plasma cells; stimulates acute-phase protein production in the liver; involved in neuronal reaction to injury [10] [9]. |

| IL-12 [8] | Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, Monocytes [10] | Activates NK cells and phagocytes; induces IFN-γ production; involved in tumor cytotoxicity and endotoxic shock [10]. |

| IL-17 [10] | Th17 Cells [10] | Recruits monocytes and neutrophils to infection sites; activates production of other cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) [10]. |

| IL-18 [10] | Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, Epithelial Cells [10] | Recruits monocytes and T lymphocytes; synergizes with IL-12 to induce IFN-γ production; inhibits angiogenesis [10]. |

| IFN-γ [8] [10] | T Cells, NK Cells [10] | Anti-viral effects; macrophage activation; increases neutrophil and monocyte function; upregulates MHC class I and II expression [10]. |

| GM-CSF [8] | T Cells, Macrophages, Fibroblasts [10] | Stimulates growth and differentiation of monocytes, eosinophils, and granulocytes from stem cells [10]. |

Receptor Systems and Signaling Mechanisms

Inflammatory cytokines exert their effects by binding to specific cell-surface or intracellular receptors, initiating complex intracellular signaling cascades. The major receptor families involved include those coupled to Janus kinases (JAKs), the IL-1 receptor family, and the TNF receptor superfamily.

JAK-STAT Coupled Receptor Systems

Cytokines such as IL-6 signal through receptors that are associated with the JAK-STAT pathway. The binding of IL-6 to its membrane-bound IL-6R (CD126) triggers the recruitment of a signal-transducing subunit, gp130 (CD130). This assembly activates the receptor-associated JAK kinases, which phosphorylate and activate STAT transcription factors. The phosphorylated STATs dimerize and translocate to the nucleus to drive the expression of target genes, including acute-phase proteins [10]. This pathway is a classic example of paracrine and endocrine signaling, influencing both immune and non-immune cells.

Figure 1: IL-6 JAK-STAT signaling pathway. IL-6 binding induces receptor dimerization, JAK kinase activation, STAT protein phosphorylation and dimerization, and nuclear translocation to regulate gene expression.

IL-1 Receptor/Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Family

The IL-1 system exemplifies a tightly regulated inflammatory pathway. IL-1β binds to the IL-1 Receptor type 1 (IL-1R1), initiating a signaling cascade that culminates in the activation of NF-κB, a master regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression. A critical natural regulator of this system is the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1ra), which binds to IL-1R1 without initiating signaling, thus acting as a competitive inhibitor. Additionally, the decoy receptor IL-1R2 (which exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms) can bind IL-1 ligands but lacks signaling capability, further fine-tuning the IL-1 response [9]. This autocrine and paracrine regulatory mechanism is vital for preventing excessive inflammation.

Table 2: Key Receptor Systems and Signaling Pathways

| Cytokine | Receptor System | Signaling Pathway | Key Regulatory Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β [9] | IL-1R1 (Signaling), IL-1R2 (Decoy), IL-1ra (Inhibitor) [9] | NF-κB Activation, MAPK [9] | IL-1ra competitively inhibits IL-1β; Soluble IL-1R2 acts as a molecular sink [9]. |

| TNF-α [9] | TNFR1 (Ubiquitous), TNFR2 (Immune cells) [9] | NF-κB, Apoptosis (via Caspases), SAPK [9] | Soluble TNFR (sTNFRp55/p75) binds circulating TNF, inhibiting receptor interaction [9]. |

| IL-6 [10] | IL-6R (CD126) & gp130 (CD130) [10] | JAK-STAT [10] | Soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R) can mediate trans-signaling [10]. |

| IFN-γ [10] | CDw119 (IFNGR1) [10] | JAK-STAT [10] | - |

| IL-12 [10] | CD212 [10] | JAK-STAT [10] | - |

TNF Receptor Superfamily

TNF-α signaling is mediated through two distinct cell surface receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2. TNFR1 is ubiquitously expressed and its engagement can lead to either NF-κB-mediated cell survival and inflammation or caspase-activated apoptosis, depending on cellular context. TNFR2 expression is more restricted to immune cells and primarily promotes cell survival and proliferation. The activity of TNF-α is regulated by soluble forms of its receptors (sTNFRp55 and sTNFRp75), which sequester the cytokine in the circulation, preventing it from interacting with membrane-bound receptors [9].

Figure 2: TNF-α signaling and regulation. TNF-α binding to TNFR1 or TNFR2 triggers divergent downstream effects. Soluble TNF receptors act as endogenous inhibitors.

Experimental Methodologies for Cytokine Research

Quantifying Cytokine Expression and Secretion

A foundational methodology in cytokine research is the accurate measurement of cytokine levels. The Cytokine Panel is a blood test that uses immunoassay techniques (e.g., ELISA or multiplex bead-based assays) to simultaneously quantify the concentrations of multiple cytokines in serum, plasma, or cell culture supernatant [2]. This is critical for diagnosing inflammatory conditions and monitoring therapeutic responses. For gene expression analysis, Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) is used to measure the relative abundance of cytokine mRNA transcripts from isolated cell populations or tissues, providing insights into transcriptional regulation [9].

Protocol: Cell Stimulation and Cytokine Measurement via ELISA

- Cell Preparation: Isolate primary immune cells (e.g., human peripheral blood mononuclear cells - PBMCs) or use a relevant immortalized cell line. Culture cells in an appropriate medium.

- Stimulation: Stimulate cells with an appropriate agonist. For pro-inflammatory cytokine induction, use E. coli Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at a concentration of 100 ng/mL for 24 hours [9].

- Sample Collection: Post-incubation, centrifuge the cell culture plate or tube at 300 x g for 10 minutes. Carefully aspirate the supernatant for cytokine analysis.

- ELISA Execution:

- Coat a 96-well plate with a capture antibody specific to the cytokine of interest (e.g., anti-human IL-1β).

- Block the plate to prevent non-specific binding.

- Add samples and standards (recombinant cytokine of known concentration) to the plate and incubate.

- After washing, add a biotinylated detection antibody specific to the same cytokine.

- Add an enzyme-conjugated streptavidin solution.

- Add the enzyme's substrate solution to develop a colorimetric signal.

- Stop the reaction and measure the absorbance using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve from the known standards and calculate the cytokine concentration in the unknown samples.

Mapping Cell-Cell Communication Networks

Advanced single-cell technologies now allow for the deconvolution of complex cytokine-mediated communication between different cell types in a tissue. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-Seq) enables the profiling of gene expression in individual cells [11]. From this data, the co-expression of ligands (e.g., cytokines) in one cell type and their cognate receptors in another can be computationally inferred to map potential autocrine and paracrine signaling networks within the tissue microenvironment [11].

Protocol: Inferring CCC from scRNA-Seq Data

- Single-Cell Suspension & Sequencing: Create a single-cell suspension from the tissue of interest (e.g., synovial tissue from an arthritis model). Process the cells using a platform like 10x Genomics to generate barcoded scRNA-Seq libraries, which are then sequenced.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Use computational pipelines (e.g., Cell Ranger) to align sequencing reads to a reference genome, quantify gene expression, and perform quality control to obtain a gene expression matrix.

- Cell Clustering & Annotation: Cluster cells based on their gene expression profiles using tools like Seurat or Scanpy. Annotate cell types using known marker genes (e.g., CD68 for macrophages, CD3E for T cells).

- Ligand-Receptor Interaction Analysis: Input the annotated expression data into specialized CCC analysis tools such as CellPhoneDB, NicheNet, or CellChat. These tools use curated databases of ligand-receptor pairs to identify statistically significant interactions between user-defined cell types.

- Visualization & Validation: Visualize the inferred communication networks as circle plots, heatmaps, or hierarchy plots. Key interactions (e.g., macrophage-derived IL1B -> IL1R1 on fibroblasts) should be validated using orthogonal methods like immunohistochemistry or functional assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cytokine Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Examples / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines [10] [9] | Used as stimulants in cell-based assays to study cytokine function, signaling, and downstream effects. | Recombinant human IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies [10] [9] | Block the activity of specific cytokines or their receptors; used for functional validation and as therapeutic prototypes. | Anti-human TNF-α, Anti-human IL-6R. |

| Pathway Databases [12] | Provide curated, computer-readable pathway models for analysis and hypothesis generation. | WikiPathways [12], Reactome [12], KEGG [12]. |

| Interaction Databases [12] | Source of known protein-protein and ligand-receptor interactions for network analysis. | BioGRID, IntAct [12], STRING [12]. |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits [2] | Gold-standard for quantitative measurement of specific cytokine protein levels in biological samples. | IL-1β ELISA Kit, TNF-α ELISA Kit. |

| JAK/STAT Inhibitors [10] | Small molecule inhibitors used to dissect specific signaling pathways in functional studies. | JAK inhibitor I (broad-spectrum), Tofacitinib (JAK1/3 selective). |

| Men 10208 | Men 10208, CAS:129781-07-3, MF:C61H75N15O12, MW:1210.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mepenzolate Bromide | Mepenzolate Bromide, CAS:76-90-4, MF:C21H26BrNO3, MW:420.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Figure 3: Typical workflow for cytokine signaling research, from hypothesis to validation.

Cytokine Signaling Cascades and Intracellular Transduction Pathways

1. Introduction

Within the inflammatory response, cytokines function as critical signaling molecules, primarily through autocrine (acting on the same cell) and paracrine (acting on nearby cells) mechanisms. Understanding the intricate intracellular transduction pathways they activate is fundamental to dissecting disease pathogenesis and developing targeted therapeutics. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the core signaling cascades initiated by inflammatory cytokines, focusing on the JAK-STAT, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways.

2. Core Inflammatory Cytokine Signaling Pathways

2.1 The JAK-STAT Pathway Cytokines such as IL-6, IFNs, and IL-2 bind to type I/II cytokine receptors, which are associated with Janus Kinases (JAKs). Receptor dimerization brings JAKs into proximity, leading to their trans-phosphorylation and activation. The JAKs then phosphorylate tyrosine residues on the receptor cytoplasmic tails, creating docking sites for STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins. Upon recruitment, STATs are phosphorylated by JAKs, dimerize, and translocate to the nucleus to drive the transcription of target genes.

2.2 The NF-κB Pathway The pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1 are potent activators of the NF-κB pathway. TNF-α binding to its receptor (TNFR1) leads to the recruitment of adaptor proteins (TRADD, TRAF2) and the formation of a signaling complex that activates the IKK complex. IKK phosphorylates the inhibitory protein IκBα, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This releases the NF-κB dimer (typically p50/p65), allowing its nuclear translocation and the initiation of gene expression for numerous inflammatory mediators.

2.3 The MAPK Pathway Multiple cytokine families, including TNF and IL-1, activate the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways. This involves a three-tiered kinase cascade: a MAPK Kinase Kinase (MAP3K) is activated, which then phosphorylates and activates a MAPK Kinase (MAP2K), which in turn phosphorylates and activates a MAPK (e.g., ERK, JNK, p38). Activated MAPKs phosphorylate a wide range of cytosolic and nuclear targets, including transcription factors like AP-1, to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory responses.

3. Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Cytokines and Their Primary Signaling Pathways

| Cytokine | Receptor Family | Primary Intracellular Pathway | Key Transcription Factor(s) Activated |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | TNFR | NF-κB, MAPK (JNK/p38) | NF-κB (p65/p50), AP-1 |

| IL-1β | IL-1R | NF-κB, MAPK (p38) | NF-κB (p65/p50), AP-1 |

| IL-6 | GP130 (Type I Cytokine) | JAK-STAT | STAT3, STAT1 |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) | Type II Cytokine | JAK-STAT | STAT1 |

| IL-2 | Common Gamma Chain (Type I) | JAK-STAT | STAT5 |

Table 2: Common Research Assays for Pathway Analysis

| Assay Type | Target/Readout | Application in Cytokine Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry | Phosphorylation status of proteins (e.g., p-STAT, p-p38) | Single-cell analysis of pathway activation in mixed cell populations. |

| Western Blot | Protein expression and phosphorylation | Semi-quantitative validation of pathway component activation. |

| ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | Cytokine concentration (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) | Quantifying cytokine secretion in autocrine/paracrine contexts. |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | Transcription factor DNA-binding activity | Detecting NF-κB or STAT binding to DNA sequences. |

| Reporter Gene Assay | Transcriptional activity (e.g., Luciferase under NF-κB promoter) | Functional assessment of pathway activation downstream of kinase events. |

4. Experimental Protocol: Assessing JAK-STAT Activation

Title: Protocol for JAK-STAT Pathway Activation and Detection via Western Blot

Objective: To stimulate cells with a cytokine (e.g., IL-6) and detect the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3.

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HepG2)

- Recombinant human IL-6

- Cell culture media and serum

- Phosphatase and protease inhibitors

- Lysis Buffer (RIPA buffer)

- Nuclear Extraction Kit

- Antibodies: anti-p-STAT3 (Tyr705), anti-STAT3 (total), anti-Lamin B1 (nuclear marker), anti-β-Actin (cytosolic marker)

- SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting equipment

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Starvation: Culture cells to 80% confluence. Serum-starve cells for 4-6 hours to reduce basal signaling activity.

- Cytokine Stimulation: Stimulate cells with IL-6 (e.g., 50 ng/mL) for a time-course (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Cell Lysis:

- Whole Cell Lysate: Aspirate media, wash with cold PBS, and lyse cells in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing inhibitors.

- Nuclear/Cytosolic Fractionation: Use a commercial kit to separate nuclear and cytosolic fractions post-stimulation.

- Protein Quantification: Determine protein concentration using a BCA or Bradford assay.

- Western Blotting: Resolve 20-30 μg of protein per lane by SDS-PAGE. Transfer to a PVDF membrane. Block with 5% BSA.

- Immunoblotting: Incubate membranes with primary antibodies (anti-p-STAT3, anti-STAT3) overnight at 4°C. Use appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Develop using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

- Membrane Stripping and Reprobing: Strip the membrane and re-probe for loading controls (β-Actin for whole cell/cytosolic, Lamin B1 for nuclear).

Data Interpretation: Phospho-STAT3 levels should increase in whole cell lysates post-stimulation, followed by an increase in the nuclear fraction, indicating successful activation and translocation.

5. Pathway Visualizations

Title: JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

Title: NF-κB Activation Pathway

Title: STAT Phosphorylation Assay Workflow

6. The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cytokine Signaling Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines | To stimulate specific pathways in cell culture models. | Human recombinant IL-6, TNF-α. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect activated (phosphorylated) forms of signaling proteins via Western Blot or Flow Cytometry. | Anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705). |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Chemically inhibit specific kinases to establish causal relationships in signaling. | JAK Inhibitor (Ruxolitinib), IKK Inhibitor (IKK-16). |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block degradation of IκB, preventing NF-κB activation, used for mechanistic studies. | MG-132. |

| Nuclear Extraction Kits | Isolate nuclear and cytosolic fractions to study transcription factor translocation. | NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents. |

| siRNA/shRNA | Knock down expression of specific pathway components (e.g., JAK1, STAT3) to assess function. | Silencer Select Pre-designed siRNAs. |

| Reporter Assay Systems | Measure transcriptional activity downstream of a pathway (e.g., NF-κB Luciferase Reporter). | Cignal Lenti Reporter Assays. |

Physiological Roles in Immune Homeostasis and Tissue Repair

The immune system's role extends far beyond pathogen defense to encompass critical physiological functions in maintaining tissue homeostasis and facilitating repair. Central to these processes are intricate networks of autocrine and paracrine signaling mediated by cytokines, which coordinate cellular responses across different tissues and pathological conditions [13] [14]. This regulatory framework ensures a precise balance between pro-inflammatory responses necessary for initiating repair and anti-inflammatory mechanisms required for resolving inflammation and restoring tissue function. Dysregulation of these signaling pathways contributes significantly to chronic inflammatory states and impaired healing, particularly evident in conditions such as diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers, and venous leg ulcers [13]. Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics and spatial biology have revealed unprecedented complexity in cytokine responses, demonstrating highly cell-type-specific effects that underlie both physiological homeostasis and pathological states [15] [16]. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of how immune cells, particularly through cytokine signaling networks, maintain tissue integrity and drive repair processes, with implications for therapeutic development across a spectrum of inflammatory and degenerative diseases.

Cytokine Networks in Tissue Repair

Orchestrating the Repair Cascade

Tissue repair represents a finely orchestrated sequence of events involving numerous immune cell types and their signaling molecules. The process initiates with platelet activation and coagulation, which forms a provisional matrix and releases key growth factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [13]. These early signals establish a chemotactic gradient that recruits innate immune cells to the injury site. Neutrophils arrive first, clearing pathogens and cellular debris through phagocytosis and releasing proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species [13]. Subsequently, monocytes enter the tissue and differentiate into macrophages, which undergo a dynamic phenotypic transition from pro-inflammatory (M1) to anti-inflammatory (M2) states—a critical switch that determines the progression from inflammation to resolution and regeneration [13].

The macrophage transition from M1 to M2 phenotype represents a pivotal checkpoint in tissue repair. M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β that maintain an inflammatory environment, while M2 macrophages produce anti-inflammatory factors including IL-10 and TGF-β that promote tissue repair [13]. This transition is regulated by a complex interplay of signals from the tissue microenvironment, with TGF-β playing a particularly crucial role. Recent research has elucidated that TGF-β1 can signal through autocrine mechanisms without dissociation from its latent complex when bound to integrin αvβ8, revealing a previously unrecognized layer of regulation in inflammatory resolution [17].

Regulatory T Cells as Orchestrators of Tissue Regeneration

Beyond innate immune mechanisms, adaptive immune cells—particularly regulatory T cells (Tregs)—play indispensable roles in tissue repair and regeneration. Originally characterized for their immunosuppressive functions, Tregs are now recognized as active contributors to tissue repair across multiple organs including skeletal muscle, heart, liver, kidneys, and skin [14]. Tissue-resident Tregs exhibit organ-specific functional specialization and contribute to repair through multiple mechanisms: suppression of excessive inflammation, direct secretion of growth factors, and support of stem cell function.

In skeletal muscle repair, Tregs accumulate following injury and facilitate the regeneration process by creating a permissive environment for muscle stem cells (MuSCs) to proliferate and differentiate [14]. Similarly, in cardiac tissue, Tregs have been shown to modulate the inflammatory response following myocardial infarction, reducing adverse remodeling and promoting functional recovery [14]. These diverse functions are enabled by the remarkable plasticity of Tregs, which can adopt distinct phenotypic states tailored to specific tissue environments. The therapeutic potential of harnessing Tregs for regenerative medicine is underscored by studies demonstrating that selective depletion of Tregs significantly impairs tissue repair across multiple organ systems [14].

Table 1: Key Immune Cell Types and Their Roles in Tissue Repair

| Cell Type | Primary Functions | Key Signaling Molecules | Tissue Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 Macrophages | Pathogen clearance, debris phagocytosis, inflammation initiation | TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS | Ubiquitous; all injured tissues |

| M2 Macrophages | Inflammation resolution, matrix deposition, angiogenesis | IL-10, TGF-β, VEGF | Ubiquitous; all injured tissues |

| Tissue Tregs | Immune suppression, stem cell support, tissue remodeling | Amphiregulin, TGF-β, IL-10 | Tissue-specific adaptations |

| Neutrophils | Early responder, antimicrobial defense, matrix modification | MMPs, ROS, chemokines | Ubiquitous; early phase only |

| Platelets | Hemostasis, initial growth factor release | PDGF, TGF-β, VEGF | Ubiquitous; initial injury response |

Maintaining Immune Homeostasis

Cytokine Signaling Networks

Immune homeostasis depends on precisely balanced cytokine networks that maintain functional equilibrium across tissues. The Immune Dictionary project has systematically cataloged transcriptomic responses of over 17 immune cell types to 86 cytokines, revealing extraordinary specificity in cytokine-cell interactions [15]. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that most cytokines induce highly cell-type-specific responses, with distinct gene expression programs activated in different cell types by the same cytokine. For example, the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β induces different gene programs in nearly every immune cell type, enabling a coordinated multicellular response despite using a common signaling molecule [15].

The CytoSig database further elucidates these complex signaling networks by modeling cytokine signaling activities from transcriptomic profiles [16]. This computational framework integrates 20,591 transcriptome profiles of human cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor responses, enabling prediction of signaling activities in diverse physiological and pathological contexts. Such approaches reveal that cytokine pleiotropy—where a single cytokine can have multiple different effects—largely results from cell-type-specific interpretation of shared signals rather than from inherent biochemical redundancy [16]. This understanding fundamentally shifts how we conceptualize cytokine networks in homeostasis and disease, emphasizing the importance of cellular context in determining functional outcomes.

Chromatin Regulation of Immune Responsiveness

Epigenetic mechanisms represent another critical layer of regulation in immune homeostasis. Naïve CD8+ T lymphocytes exposed to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-15 and IL-21 undergo chromatin remodeling that enhances their antigen responsiveness without full activation [18]. This "cytokine priming" creates a poised state characterized by increased chromatin accessibility at genes involved in T cell signaling, activation, effector differentiation, and negative regulation [18]. The primed cells demonstrate heightened sensitivity to subsequent antigen encounter, illustrating how cytokine signals can tune the functional potential of immune cells through epigenetic mechanisms.

Notably, cytokine priming and antigen stimulation induce partially overlapping but distinct chromatin accessibility profiles, suggesting complementary but non-identical mechanisms of immune cell preparation [18]. This priming phenomenon represents a homeostatic mechanism that allows the immune system to maintain a heightened state of readiness without initiating inappropriate activation, thereby balancing responsiveness with control. Dysregulation of such priming mechanisms may contribute to both autoimmune pathology and inadequate anti-tumor immunity.

Table 2: Experimental Platforms for Analyzing Immune Signaling Networks

| Platform/Technology | Primary Application | Key Capabilities | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CytoSig [16] | Cytokine activity prediction from transcriptomic data | Database of 20,591 cytokine response profiles; predictive modeling of signaling activities | Based primarily on in vitro data; requires validation in physiological contexts |

| Immune Dictionary [15] | Comprehensive cytokine response catalog | Single-cell transcriptomic responses to 86 cytokines across >17 immune cell types | Mouse model; human relevance requires confirmation |

| CellNEST [19] | Cell-cell communication mapping from spatial transcriptomics | Identifies relay networks (ligand-receptor-ligand-receptor chains); single-cell resolution | Computational inference; requires experimental validation |

| ATAC-seq [18] | Chromatin accessibility analysis | Genome-wide mapping of open chromatin regions; reveals regulatory landscape | Does not directly measure gene expression or protein binding |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Mapping Cell-Cell Communication Networks

Understanding the spatial organization of immune signaling requires sophisticated analytical approaches. CellNEST represents a significant methodological advance by leveraging graph neural networks to decipher cell-cell communication patterns from spatial transcriptomics data [19]. This computational framework introduces relay-network communication detection, identifying multi-step signaling cascades (ligand-receptor-ligand-receptor) that form communication networks across multiple cells. Unlike methods limited to single ligand-receptor pairs, CellNEST reconstructs extended communication pathways that more accurately reflect the complexity of immune signaling in tissues.

The methodology involves several key steps: First, spatial transcriptomic data is processed to identify individual cells or spots and their gene expression profiles. Next, a graph attention network (GAT) encoder models the spatial relationships between cells, incorporating both expression data and physical proximity [19]. Finally, contrastive learning through Deep Graph Infomax (DGI) enables unsupervised identification of significant communication events without requiring predefined ground truth. This approach has been validated across multiple biological contexts, including T cell homing in lymph nodes and cancer microenvironment communication, demonstrating its utility for uncovering novel signaling networks in tissue homeostasis and repair [19].

Systematic Cytokine Response Profiling

The Immune Dictionary project established a comprehensive experimental framework for characterizing cytokine responses at single-cell resolution [15]. The methodology involves injecting individual cytokines subcutaneously in mice, followed by collection of skin-draining lymph nodes 4 hours post-injection—a timepoint capturing early transcriptomic responses. Single-cell RNA sequencing of over 386,000 cells enabled mapping of responses across more than 1,400 cytokine-cell type combinations [15].

Critical to this approach was rigorous quality control, including verification of batch-to-batch consistency and accurate cell type identification. The resulting dataset revealed an average of 51 differentially expressed genes per cytokine-cell type combination, with 72% being upregulated rather than downregulated [15]. This systematic profiling identified previously uncharacterized immune cell polarization states, such as IL-18-induced polyfunctional natural killer cells, expanding our understanding of the functional potential within immune cell populations. The accompanying analytical tool, Immune Response Enrichment Analysis (IREA), enables researchers to extract cytokine activities and immune cell states from their own transcriptomic data, facilitating translation of these findings to diverse experimental contexts [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features | Representative Examples/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Receptor Databases | Curated collections of known interactions for communication analysis | Foundation for computational prediction of cell-cell signaling | Databases integrated in CellNEST, NicheNet, CellChat [19] |

| Cytokine Response Signatures | Reference profiles for inferring cytokine activities from transcriptomic data | Enable deconvolution of active signaling pathways from bulk or single-cell data | CytoSig database (1,307 high-quality signatures) [16] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Mapping gene expression in tissue context with spatial resolution | Preservation of architectural relationships between cells | Visium, Visium HD, MERFISH [19] |

| Graph Neural Network Algorithms | Pattern recognition in spatially-resolved expression data | Identification of complex communication networks beyond pairwise interactions | CellNEST GAT encoder with DGI contrastive learning [19] |

| Chromatin Accessibility Tools | Mapping regulatory element activity and transcription factor occupancy | Reveals epigenetic basis of cellular responsiveness | ATAC-seq [18] |

| Mazethramycin | Mazethramycin, CAS:68373-96-6, MF:C17H19N3O4, MW:329.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MCHr1 antagonist 2 | MCHr1 antagonist 2, MF:C23H21FN2O5, MW:424.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

TGF-β Activation and Signaling Pathway

Cytokine Response Profiling Workflow

Chronic Wound Immune Dysregulation

The intricate interplay between immune homeostasis and tissue repair represents a frontier in understanding organismal physiology and developing novel therapeutic strategies. The emerging paradigm recognizes immune cells not merely as defenders against pathogens, but as essential architects of tissue integrity and restoration. Key advances include the recognition of highly cell-type-specific cytokine responses that enable precise coordination of repair processes [15], the discovery of non-canonical signaling mechanisms such as release-independent TGF-β activation [17], and the development of computational tools that can decode complex cell-cell communication networks from spatial transcriptomic data [19].

Future research directions will need to address several critical challenges: First, translating insights from murine models to human physiology, particularly given the species-specific differences in immune responses. Second, integrating multi-omics approaches to connect transcriptional regulation, protein signaling, and metabolic reprogramming in immune cells during tissue repair. Third, developing therapeutic strategies that can selectively modulate specific aspects of immune signaling without disrupting the delicate balance required for homeostasis. The rapidly advancing toolkit for analyzing and manipulating immune responses—including the resources described in this whitepaper—provides an exciting foundation for these future developments, with profound implications for treating degenerative, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases.

Pathological Implications in Autoimmunity and Chronic Inflammation

Autoimmune diseases represent a complex group of disorders characterized by immune dysregulation, chronic inflammation, and multiorgan involvement, affecting approximately one in ten individuals with rising incidence, particularly in Western countries [20]. A hallmark of these conditions is the breakdown of self-tolerance, leading to the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy tissues [21]. Within this pathological framework, the autocrine and paracrine signaling of inflammatory cytokines has emerged as a critical mechanism driving disease pathogenesis. Cytokines, small signaling proteins produced by a broad range of cells including immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, typically function through specific receptors on target cells and can signal in autocrine (acting on the same cell), paracrine (acting on nearby cells), or endocrine (systemic) manners [22].

The network dynamics of cytokine production and response govern stimulus-specific autocrine and paracrine functions that significantly impact disease progression [3]. In autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and multiple sclerosis (MS), dysregulated cytokine signaling creates self-perpetuating inflammatory loops that sustain chronic inflammation and mediate tissue damage [20] [21]. This whitepaper examines the pathological implications of these signaling mechanisms in autoimmunity, with particular focus on their role in immune cell senescence, therapeutic targeting challenges, and emerging research methodologies.

Cytokine Signaling Mechanisms in Autoimmunity

Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling Paradigms

Cytokines function as crucial immunomodulating agents through three primary signaling modalities: autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine. Autocrine signaling occurs when a cell secretes cytokines that bind to receptors on its own surface, thereby amplifying its own response. Paracrine signaling involves cytokines acting on immediately adjacent cells, while endocrine signaling refers to cytokines circulating systemically to affect distant tissues [22]. In autoimmune pathogenesis, autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms predominate in creating localized inflammatory milieus that drive disease processes.

The functional consequences of these signaling patterns are context-dependent and determined by underlying network dynamics. Research on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production in macrophages has demonstrated that the same cytokine can serve distinct functions depending on the stimulus. In response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TNF primarily functions in a paracrine manner to activate neighboring cells, whereas in response to CpG DNA, it operates through autocrine signaling to extend the duration of NF-κB activity and shape gene expression programs [3].

Key Cytokine Families in Autoimmune Pathogenesis

Several cytokine families play particularly significant roles in autoimmune pathogenesis through their autocrine and paracrine actions:

TNF Superfamily: TNF-α is a pivotal inflammatory cytokine that coordinates innate and adaptive immune responses. It is produced by macrophages, T cells, and other immune cells upon activation and contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous autoimmune diseases including RA, Crohn's disease, and psoriasis [3]. TNF-α promotes inflammation through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, enhancing leukocyte migration, increasing vascular permeability, and inducing the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Interleukin Family: Multiple interleukins contribute to autoimmune pathology through complex signaling networks. IL-6, produced by macrophages, B cells, and other immune cells, promotes Th17 cell differentiation while inhibiting Treg function, creating an imbalance that drives autoimmunity [21]. IL-17, primarily secreted by Th17 cells, acts in a paracrine manner on stromal and epithelial cells to induce chemokine production and neutrophil recruitment, particularly in diseases like psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis [20].

Interferons: Type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) and type II interferon (IFN-γ) play crucial roles in autoimmune pathogenesis. In SLE, a characteristic "interferon signature" reflects the pervasive effects of IFN-α on immune cell function, while IFN-γ contributes to macrophage activation and pathogenesis in RA and multiple sclerosis [21].

Chemokines: This specialized subset of cytokines functions primarily in a paracrine manner to direct leukocyte migration and positioning. In autoimmune diseases, chemokines such as CXCL13 (B-cell attraction) and CCL2 (monocyte recruitment) create organizational networks within inflamed tissues that sustain chronic inflammation [21].

Table 1: Major Cytokine Classes and Their Roles in Autoimmunity

| Cytokine Family | Key Members | Primary Cellular Sources | Autoimmune Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF Superfamily | TNF-α | Macrophages, T cells | RA, Crohn's disease, Psoriasis [3] |

| Interleukins | IL-6, IL-17, IL-10, IL-1 | Macrophages, T cells, Dendritic cells | SLE, RA, Psoriasis, Ankylosing Spondylitis [20] [21] |

| Interferons | IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ | Plasmacytoid DCs, T cells, Macrophages | SLE, Multiple Sclerosis [21] |

| Chemokines | CXCL13, CCL2, CX3CL1 | Stromal cells, Macrophages, Endothelial cells | RA, Multiple Sclerosis, Lupus [21] |

Mechanistic Insights: From Signaling Dysregulation to Pathology

Immune Cell Senescence and SASP

A key mechanism linking autocrine/paracrine signaling to chronic inflammation in autoimmunity is the induction of immune cell senescence and the development of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Senescent immune cells become irreversibly arrested in the cell cycle, exhibit antimetabolic characteristics, and secrete pro-inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ, which disrupt immune homeostasis [21].

In T lymphocytes, senescence leads to distinctive phenotypic changes including loss of costimulatory receptors (CD27/CD28) and gain of NK-like markers (KLRG1, CD57). These senescent T cells demonstrate metabolic dysregulation, with impaired glucose transporter Glut1 and fatty acid transporters FATP2/3, along with mitochondrial dysfunction that further compromises T cell fitness [21]. The sustained exposure to cytokines and DNA damage in the autoimmune environment leads to persistent activation of ERK and P38 MAPK cascades, which activate cell cycle regulators (P53, P21, P16) that enforce cell cycle arrest and telomerase suppression—hallmarks of senescence [21].

In rheumatoid arthritis, the inflammatory milieu polarizes CD4+ T cells toward the pro-inflammatory Th17 phenotype with increased secretion of IL-17 and IL-22. Simultaneously, Tregs decrease in number and function, limiting their TGF-β and IL-10-mediated control of immune responses. This Th17/Treg imbalance is further enhanced by IL-6, which induces generation of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells that strongly stimulate autoreactive B lymphocytes to enhance autoantibody production and tissue destruction [21].

Network Dynamics and Feedback Loops

The pathological persistence of autoimmune inflammation is maintained by complex feedback loops within cytokine networks. Cytokines themselves trigger the release of other cytokines and lead to increased oxidative stress, making them central players in chronic inflammation [22]. This positive feedback amplification creates self-sustaining inflammatory circuits that are resistant to normal resolution mechanisms.

For instance, in the TNF signaling network, the same cytokine can have dramatically different functions depending on the cellular context and signaling dynamics. Research has revealed that network dynamics of MyD88 and TRIF signaling determine the stimulus-specific autocrine and paracrine functions of TNF [3]. This explains why in response to LPS, TNF does not have an autocrine function in amplifying the NF-κB response, while in response to CpG DNA, autocrine TNF extends the duration of NF-κB activity and shapes gene expression programs [3].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Autocrine and Paracrine Functions of TNF

| TLR Agonist | Adaptor Proteins | TNF Signaling Mode | Functional Outcome | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | MyD88 and TRIF | Paracrine (not autocrine) | Potent activation of neighboring cells | Systems biology modeling with experimental confirmation in BMDMs [3] |

| CpG DNA | MyD88 | Autocrine | Extended duration of NF-κB activity, shaped gene expression | Prediction and validation in wild-type vs. knockout models [3] |

Mathematical modeling approaches have provided valuable insights into these complex network behaviors. Of the mechanistic mathematical models developed for autoimmune diseases, approximately 70% are constructed as nonlinear systems of ordinary differential equations, while others utilize partial differential equations, integro-differential equations, Boolean networks, or probabilistic models [23]. These models consistently describe core components of the immune system, particularly T-cell response, cytokine influence, and macrophage involvement in autoimmune processes [23].

Quantitative Data Analysis in Autoimmune Research

The complexity of cytokine networks in autoimmunity necessitates sophisticated quantitative approaches to elucidate pathological mechanisms. Bibliometric analysis reveals a steadily growing research output in autoimmune disease-associated pathologies, with the United States and China as the leading contributors, collectively publishing over 2,400 papers in this domain [24]. Research trends show increasing focus on immunotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors as potential treatment strategies [24].

Analysis of immune cell populations in autoimmune conditions provides quantitative insights into disease mechanisms. In difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis, immunological profiling reveals a marked reduction in regulatory T cells accompanied by an increased Th17/Treg ratio, reflecting disrupted immune balance that correlates with heightened disease activity [20]. Similarly, complement activation products measured on B lymphocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets serve as sensitive indicators of disease activity in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) [20].

Proteome-wide analyses have identified specific plasma proteins causally associated with autoimmune disease risk. Mendelian randomization studies have revealed seven proteins associated with psoriatic arthritis susceptibility, notably interleukin-10 (IL-10), which is inversely linked with disease risk, and apolipoprotein F (APOF), which shows a positive association [20]. In ankylosing spondylitis, eight plasma proteins including AIF1, TNF, FKBPL, AGER, ALDH5A1, and ACOT13 demonstrate causal relationships with disease risk [20].

Table 3: Quantitative Methodologies in Autoimmune Disease Research

| Methodology | Key Applications | Representative Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systems Biology Modeling | Understanding TNF regulatory modules | TLR-specific autocrine/paracrine TNF functions | [3] |

| Bibliometric Analysis | Research trend identification | Immunotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors as emerging hotspots | [24] |

| Mendelian Randomization | Causal inference in disease pathogenesis | IL-10 and APOF as risk proteins in PsA; multiple proteins in AS | [20] |

| Senescent Cell Profiling | Immune aging characterization | CD28- T cells in RA, T1D, MS with CX3CR1 expression | [21] |

| Mathematical Modeling | Pathophysiology quantification | 38 models identified for 13 autoimmune conditions | [23] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Model Systems and Validation

The iterative systems biology approach has proven particularly powerful for elucidating cytokine functions in autoimmunity. This methodology involves developing quantitative understandings of regulatory modules controlling cytokine production at multiple levels—mRNA synthesis and processing, mRNA half-life, translation, and protein processing and secretion [3]. By linking models of cytokine production to models of signaling modules (e.g., TLR, TNFR, and NF-κB pathways), researchers can systematically investigate cytokine functions during inflammatory responses to diverse stimuli.

For TNF research, this approach has involved several key methodological steps: (1) quantitative measurement of TNF secretion in wild-type versus adaptor protein-deficient (trif-/- and myd88-/-) bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated with TLR agonists; (2) assessment of TNF production at mature mRNA level by RT-PCR; (3) measurement of nascent, intron-containing transcripts to distinguish transcriptional from post-transcriptional control; and (4) computational modeling integrated with experimental validation to test predictions about autocrine versus paracrine functions [3].

Synovial joint-on-a-chip models represent another innovative experimental platform that accurately mimics the joint microenvironment by integrating fluid dynamics, mechanical stimulation, and intercellular communication [20]. This technology facilitates preclinical modeling of rheumatoid arthritis, enabling precise evaluation of inflammation, drug efficacy, and personalized therapeutic strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cytokine Signaling Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs) | Primary cell model for innate immune signaling | Investigation of TLR-responsive pathways and TNF production [3] |

| TLR Agonists (LPS, CpG DNA) | Specific activation of pattern recognition receptors | Dissection of MyD88 vs. TRIF-dependent signaling pathways [3] |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits | Quantitative protein measurement | Assessment of TNF, IL-6, and other cytokine secretion [3] |

| Senescence-Associated Biomarkers (CD57, KLRG1) | Identification of senescent immune cells | Flow cytometric analysis of T-cell senescence in autoimmunity [21] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detection of signaling pathway activation | Analysis of MAPK (ERK, P38) and NF-κB pathway activity [21] |

| Recombinant Cytokines and Receptor Fc Fusion Proteins | Pathway activation and inhibition studies | Functional dissection of autocrine/paracrine signaling [3] |

| Mcl1-IN-1 | Mcl1-IN-1|Mcl-1 Inhibitor For Cancer Research | Mcl1-IN-1 is a potent Mcl-1 protein inhibitor. It is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

| Mepronil | Mepronil, CAS:55814-41-0, MF:C17H19NO2, MW:269.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling in Autoimmunity

Cellular Signaling Modalities in Autoimmune Inflammation

TNF Signaling Dynamics in TLR Activation

Stimulus-Specific TNF Signaling Pathways

The pathological implications of autocrine and paracrine signaling in autoimmunity and chronic inflammation represent a complex yet crucial domain of immunological research. The context-specific functions of cytokines like TNF, determined by network dynamics of production and response, highlight the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that can become dysregulated in autoimmune conditions. The emerging understanding of immune cell senescence and the SASP provides a mechanistic link between chronic cytokine exposure and persistent inflammation that characterizes progressive autoimmune diseases.

Future research directions should focus on leveraging quantitative systems pharmacology approaches and mathematical modeling to better predict therapeutic outcomes in heterogeneous patient populations. The integration of multi-omics data, advanced experimental model systems, and targeted therapeutic interventions holds promise for disrupting the pathological autocrine and paracrine signaling loops that drive autoimmunity. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to develop precisely targeted therapies that restore immune homeostasis without compromising essential protective functions.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem where cytokine networks act as master regulators of cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. Operating through autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms, these small signaling proteins create a dynamic communication network between cancer cells and stromal components. This whitepaper examines the dualistic nature of cytokines in tumor biology, detailing their context-dependent roles as both tumor suppressors and promoters. We provide a technical analysis of key signaling pathways, experimental methodologies for cytokine research, and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these networks for cancer treatment. The intricate balance of pro- and anti-tumor cytokines represents a critical frontier for developing next-generation immunotherapies and overcoming treatment resistance.

Cytokines are small proteins or polypeptides (5-140 kDa) that function as key signaling molecules in the TME, mediating intercellular communication through autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms [25] [26]. These molecules are secreted by various cell types including immune cells, tumor cells, and stromal cells, creating a complex network that profoundly influences tumor behavior [25] [27]. The cytokine network exhibits significant functional plasticity, with many cytokines demonstrating a "double-edged sword" effect depending on context, concentration, and cellular environment [25].

Within the framework of autocrine and paracrine signaling research, cytokines establish self-sustaining loops that drive tumor progression. Autocrine signaling occurs when cancer cells secrete cytokines that bind to their own receptors, promoting self-proliferation and survival. Paracrine signaling involves cytokine-mediated communication between different cell types within the TME, facilitating cellular crosstalk that shapes the immunosuppressive landscape [28]. This bidirectional communication between malignant and stromal components represents a fundamental mechanism by which tumors evade immune destruction and promote their own growth [26] [27].

The dynamic regulation of cytokine networks is influenced by multiple factors including cytokine concentration, spatial distribution within the TME, temporal aspects of tumor development, and the evolving co-evolutionary relationship between tumors and the host immune system [25]. Understanding these complex interactions requires sophisticated experimental approaches that can capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of cytokine signaling in the TME.

The Dual Nature of Cytokines in Tumor Progression

Tumor-Suppressive Cytokines

Several cytokines demonstrate potent anti-tumor effects by activating immune effector cells, enhancing antigen presentation, and directly inhibiting tumor cell proliferation [25]. The table below summarizes key anti-tumor cytokines and their mechanisms of action.

Table 1: Key Cytokines with Demonstrated Tumor-Suppressive Effects

| Cytokine | Primary Cellular Sources | Main Anti-Tumor Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | T cells, NK cells | Inhibits tumor cell growth, promotes apoptosis, upregulates MHC-I expression on tumor cells, activates M1 macrophages and NK cells [25] |

| IL-2 | T cells | Drives clonal expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, enhances cytotoxic activity of CTLs and NK cells, induces LAK cell activation [25] |

| IL-12 | Dendritic cells, macrophages | Directs naïve T cell differentiation toward Th1 phenotype, promotes IFN-γ secretion from Th1 and NK cells, enhances tumor-lytic activity of CTLs and NK cells, suppresses angiogenesis [25] |

| TGF-β (early stage) | Neutrophils, macrophages | Reduces cell proliferation, triggers apoptosis in early tumor development [25] |

| IL-36 | Epithelial cells, immune cells | Activates host immune system, synergizes with IL-2 and IL-12 to activate T cells and induce IFN-γ production [25] |

Tumor-Promoting Cytokines

In contrast to their protective functions, many cytokines acquire tumor-promoting capabilities during cancer progression, facilitating immune evasion, metastasis, and treatment resistance [25] [26]. These cytokines create a chronic inflammatory environment that supports multiple hallmarks of cancer.

Table 2: Key Cytokines with Demonstrated Tumor-Promoting Effects

| Cytokine | Primary Cellular Sources | Main Pro-Tumor Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Macrophages, fibroblasts, tumor cells | Activates JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway, promotes tumor cell growth and prevents apoptosis, induces EMT, supports angiogenesis [25] [29] |

| TGF-β (late stage) | Macrophages, T cells | Enhances migratory and invasive abilities of tumor cells by inducing EMT, creates immunosuppressive microenvironment by reducing effector T cell function and promoting Treg development [25] [26] |

| TNF-α | Macrophages, mast cells | Induces PD-L1 overexpression in tumors, creates immunosuppressive TME, promotes resistance to targeted therapy [25] [29] |

| IL-10 | T cells, macrophages | Inhibits antigen presentation by DCs and macrophages, suppresses Th1-type immune responses, promotes Treg differentiation and longevity [25] |

| VEGF | Endothelial cells, platelets, tumor cells | Promotes angiogenesis, provides nutrients and oxygen to growing tumors [26] [27] |

| CSF-1 | Stromal cells, tumor cells | Recruits and polarizes monocytes into pro-tumor M2 macrophages [30] |

The functional duality of cytokines is particularly evident in factors like TGF-β, which exhibits stage-dependent effects—acting as a tumor suppressor in early carcinogenesis but transitioning to a potent tumor promoter in established cancers [25] [26]. This contextual duality represents a significant challenge for therapeutic targeting and underscores the importance of understanding the temporal dynamics of cytokine networks in cancer progression.

Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling Mechanisms

Fundamental Signaling Paradigms

The cytokine network operates through two primary signaling modalities that enable complex cellular crosstalk within the TME:

Autocrine Signaling: Cancer cells secrete cytokines that bind to receptors on their own surface, creating self-stimulating loops that drive uncontrolled proliferation and survival. For example, many tumors autonomously produce growth factors like EGF and FGF that sustain their expansion through autocrine mechanisms [28].

Paracrine Signaling: Stromal and immune cells within the TME secrete cytokines that influence the behavior of neighboring cancer cells, and vice versa. This bidirectional communication shapes the functional properties of the TME. A key example is the secretion of CSF-1 by tumor cells, which recruits monocytes and promotes their differentiation into pro-tumor M2 macrophages through paracrine signaling [30].

Cytokine-Mediated Cellular Crosstalk

The diagram below illustrates the complex autocrine and paracrine signaling networks between major cellular components in the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 1: Autocrine and Paracrine Cytokine Networks in TME

These signaling mechanisms establish feed-forward loops that maintain the immunosuppressive TME. For instance, tumor-derived TGF-β stimulates cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) to produce additional TGF-β and IL-6, which further enhances tumor growth and immune suppression through paracrine action on both cancer cells and infiltrating lymphocytes [26] [27]. Similarly, the IL-6-STAT-3 signaling axis creates a positive feedback loop that sustains chronic inflammation and promotes tumor progression [29].

Key Signaling Pathways in Cytokine-Mediated Tumor Progression

JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK-STAT pathway serves as a critical signaling node for multiple cytokines, including IL-6, and is frequently activated in cancer [25] [29]. The diagram below illustrates the key components and activation mechanism of this pathway.

Figure 2: JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway Activation

Chronic activation of the JAK-STAT pathway, particularly STAT-3, promotes tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms: enhancing cancer cell proliferation and survival via upregulation of cyclins and anti-apoptotic proteins; driving angiogenesis through VEGF induction; and facilitating metastasis by activating EMT programs and matrix metalloproteinases [29]. Inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 activate this pathway through binding to their cognate receptors, initiating phosphorylation cascades that ultimately lead to transcriptional activation of pro-tumorigenic genes.

NF-κB Signaling Pathway

The NF-κB pathway serves as a central regulator of inflammation-associated cancer, connecting chronic inflammation to tumor development [29] [31]. This pathway can be activated by various stimuli including TNF-α, IL-1β, and pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognizing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [31].

Table 3: Key Pro-tumorigenic Transcription Factors Activated by Cytokines

| Transcription Factor | Primary Activators | Key Target Genes | Pro-tumorigenic Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT-3 | IL-6, EGF, VEGF | Cyclin-D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, VEGF, MMP-2, MMP-9 | Cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, metastasis [29] |

| NF-κB | TNF-α, IL-1β, LPS | IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, MMP-9 | Inflammation, cell survival, angiogenesis, invasion [29] [31] |

| SMAD | TGF-β | PAI-1, SMAD7, p15, p21 | EMT, immune suppression, extracellular matrix remodeling [26] |

These signaling pathways do not operate in isolation but exhibit significant crosstalk and redundancy. For example, NF-κB can induce the expression of IL-6, which subsequently activates STAT-3, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies inflammatory signaling and promotes tumor progression [29]. Similarly, TGF-β signaling can synergize with NF-κB pathway to enhance EMT and metastasis [26].

Methodologies for Studying Cytokine Networks

Experimental Approaches for Cytokine Profiling

Comprehensive analysis of cytokine networks requires integration of multiple experimental techniques that capture both the spatial distribution and functional roles of these signaling molecules.

Table 4: Key Methodologies for Cytokine Network Analysis

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Immunoassays (Luminex, MSD) | High-throughput quantification of multiple cytokines in biological samples | Enables simultaneous measurement of 30+ analytes with small sample volumes; requires appropriate controls for matrix effects [32] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Characterization of cytokine expression patterns at single-cell resolution | Identifies cellular sources and heterogeneity in cytokine production; requires specialized bioinformatics analysis [30] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Mapping cytokine expression within tissue architecture | Preserves spatial context of cytokine signaling; lower resolution than single-cell approaches but maintains tissue organization [32] |

| Cytokine Signaling Reporter Assays | Monitoring activation of specific signaling pathways in live cells | Uses engineered reporter constructs (GFP, luciferase) under control of cytokine-responsive elements; provides dynamic rather than endpoint data [33] |

| Phospho-Flow Cytometry | Quantifying phosphorylation of signaling intermediates in single cells | Enables analysis of signaling network activation in heterogeneous cell populations; requires careful antibody validation and fixation protocols [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below compiles key research reagents and their applications for investigating cytokine networks in the tumor microenvironment.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Cytokine Network Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines | Human IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β, IFN-γ | In vitro stimulation assays, functional validation studies, dose-response experiments [25] |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Anti-IL-6, Anti-TGF-β, Anti-VEGF | Functional blockade of specific cytokine pathways, validation of cytokine dependencies [25] [30] |

| Signal Transduction Inhibitors | JAK inhibitors (Ruxolitinib), STAT-3 inhibitors, NF-κB inhibitors | Pathway perturbation studies, identification of critical signaling nodes [25] [29] |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits | Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems) | Absolute quantification of specific cytokine concentrations in biological samples [33] |

| Multiplex Bead Arrays | Luminex xMAP technology, MSD U-PLEX | High-throughput screening of cytokine profiles in conditioned media, serum, or tissue lysates [32] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Guide RNAs targeting cytokine receptors or signaling components | Genetic validation of cytokine pathway components, generation of knockout cell lines [30] |

| Mequitamium Iodide | Mequitamium Iodide, CAS:101396-42-3, MF:C21H25IN2S, MW:464.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Meralein sodium | Meralein sodium, CAS:4386-35-0, MF:C19H9HgI2NaO7S, MW:858.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow for Cytokine Signaling Analysis

The diagram below outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for characterizing cytokine networks and their functional roles in the TME.

Figure 3: Cytokine Network Analysis Workflow

This integrated approach enables researchers to move from descriptive cytokine profiling to functional validation, ultimately generating mechanistic insights into how specific cytokine networks influence tumor behavior. The workflow emphasizes the importance of combining multiple complementary techniques to overcome the limitations of individual methodologies and provide a comprehensive understanding of cytokine signaling dynamics.

Therapeutic Targeting of Cytokine Networks

Current Clinical Strategies

Targeting cytokine networks has emerged as a promising approach for cancer therapy, with several strategies showing clinical promise:

Cytokine Neutralization: Monoclonal antibodies targeting pro-tumor cytokines or their receptors can disrupt pathogenic signaling networks. For example, IL-6 blockade with siltuximab has shown efficacy in certain lymphoproliferative disorders, while TGF-β inhibitors are being investigated in multiple solid tumors [25] [26].

Receptor Antagonists: Small molecule inhibitors targeting cytokine receptors or downstream signaling components can abrogate pro-tumor signaling. JAK inhibitors have demonstrated clinical activity in myeloproliferative neoplasms driven by dysregulated cytokine signaling [25] [29].