Bayesian Identifiability: Overcoming Parameter Uncertainty in Immunology Models

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian methods for addressing parameter identifiability in immunological models.

Bayesian Identifiability: Overcoming Parameter Uncertainty in Immunology Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian methods for addressing parameter identifiability in immunological models. We explore the fundamental concepts of structural and practical non-identifiability in systems biology, detailing how Bayesian inference with informative priors can resolve these issues. The guide covers methodological implementation using modern computational tools, strategies for troubleshooting poorly-identified models, and validation techniques comparing Bayesian approaches to frequentist alternatives. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current best practices to enhance the reliability of model calibration and prediction in immunology.

What is Parameter Identifiability? Core Concepts and Challenges in Immunology

Within the context of Bayesian approaches for parameter identifiability in immunology research, distinguishing between structural and practical non-identifiability is a fundamental challenge. Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models are central to systems immunology, describing dynamics from intracellular signaling to population-level immune responses. However, the inability to uniquely estimate model parameters from data—non-identifiability—compromises predictive power and mechanistic insight. This guide provides a technical dissection of the problem, offering methodologies for diagnosis and addressing it within a Bayesian framework.

Core Definitions and Theoretical Framework

Structural Non-Identifiability: A model parameter is structurally non-identifiable if, even with perfect, noise-free experimental data of infinite quantity, it cannot be uniquely determined. This is an inherent property of the model structure, arising from redundant parameterizations or symmetries in the equations.

Practical Non-Identifiability: A model parameter is practically non-identifiable when limited, noisy, or insufficient data—common in immunological experiments—prevents its precise estimation, despite the parameter being structurally identifiable in principle. The posterior distribution in a Bayesian analysis remains flat or excessively broad along that parameter direction.

Diagnostic Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol for Structural Identifiability Analysis (Taylor Series Approach)

Objective: To determine if the model's parameters can be uniquely recovered from perfect observation of the state variables.

- Model Specification: Define the ODE system:

dx/dt = f(x, θ), with outputy = h(x, θ), wherexis the state vector (e.g., cytokine concentrations),θis the parameter vector, andyis the observable. - Compute Lie Derivatives: Repeatedly differentiate the output function

ywith respect to time, substituting in the ODEs to express derivatives solely in terms ofy,θ, and initial conditions. - Construct the Observability-Identifiability Matrix: Form a matrix from the partial derivatives of these Lie derivatives with respect to the parameters and initial states.

- Rank Test: Compute the symbolic rank of this matrix. If the rank is less than the number of unknown parameters and initial states, the model is structurally non-identifiable. Tools:

STRIKE-GOLDD(MATLAB) orSymPy(Python) for symbolic computation.

Protocol for Assessing Practical Identifiability (Bayesian Workflow)

Objective: To evaluate parameter estimability given realistic, finite, and noisy data.

- Define Priors: Specify prior distributions

P(θ)based on biological knowledge (e.g., log-normal for rate constants). - Generate Synthetic Data: Simulate the model with a known

θ_trueand add Gaussian noise commensurate with expected experimental error (e.g., 10-20% CV for flow cytometry). - Sample the Posterior: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo via Stan or PyMC) to approximate the posterior

P(θ | D) ∝ L(D | θ) * P(θ). - Analyze Posterior Marginals: Inspect the marginal posterior distributions for each parameter.

- Identifiable: Unimodal, narrow distribution.

- Practically Non-Identifiable: Flat, multimodal, or excessively wide distribution (e.g., coefficient of variation > 50%).

- Compute Correlation Matrix: High pairwise correlations (> |0.8|) in the posterior suggest identifiable combinations but individual non-identifiability.

Table 1: Characteristic Signatures of Non-Identifiability Types

| Feature | Structural Non-Identifiability | Practical Non-Identifiability |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Model structure (over-parameterization) | Data quality/quantity, noise |

| Persists with perfect data? | Yes | No |

| Bayesian Posterior Profile | Flat along manifold(s) | Locally flat or very broad |

| Likelihood Profile | Constant along manifold(s) | Has a minimum but is wide/shallow |

| Common in Immunology | Often in large, complex signaling pathways | Common in longitudinal in vivo data with sparse sampling |

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Design on Practical Identifiability (Example: T-cell Activation Model)

| Experimental Modulation | Estimated Posterior CV for Key Parameter k_act |

Identifiability Classification |

|---|---|---|

| 3 time points (0, 2, 24h) | 95% | Non-Identifiable |

| 8 time points (0-24h, dense) | 40% | Weakly Identifiable |

| 8 time points + dose-response (3 agonist levels) | 15% | Identifiable |

| 3 time points + inhibitor perturbation | 22% | Identifiable |

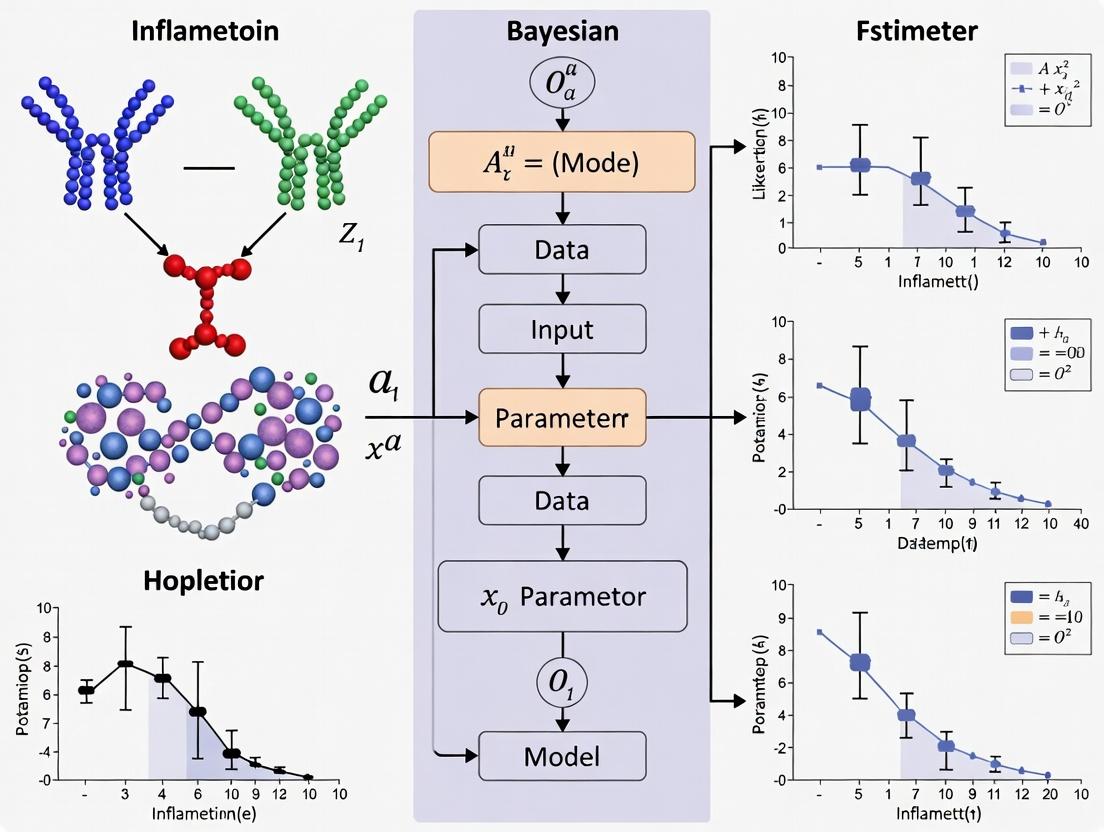

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Title: Diagnostic Flow for Non-Identifiability

Title: Posterior Distributions for Identifiability Types

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Identifiability Analysis in Immunology Models

| Item/Reagent | Function in Identifiability Analysis | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Math Software | Performs structural identifiability analysis (Lie derivatives, rank test). | MATLAB with Symbolic Toolbox + STRIKE-GOLDD, Python with SymPy |

| Probabilistic Programming Language | Implements Bayesian calibration and MCMC sampling for practical assessment. | Stan (via CmdStanR/PyStan), PyMC, TensorFlow Probability |

| Synthetic Data Generator | Creates perfect and noisy dataset for testing and protocol development. | Custom scripts in R/Python using ODE solvers (deSolve, SciPy) |

| Parameter Sensitivity Kit | Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA) to prune irrelevant parameters pre-calibration. | SALib library for Sobol' indices, PRCC analysis |

| Experimental Perturbation Agents | Breaks symmetries and provides informative data for practical identifiability. | Kinase inhibitors, cytokine receptor blockers, gene knockouts (CRISPR) |

| High-Density Time-Series Assay | Increases data density to constrain dynamic models. | Live-cell imaging, frequent flow cytometry, longitudinal scRNA-seq |

| Multi-Scale Data | Provides complementary observations to constrain different model parts. | Combine phospho-flow (signaling) with ELISA (secreted cytokines) |

For immunology research employing Bayesian inference, a rigorous two-stage approach is imperative. Structural identifiability analysis is a prerequisite to ensure the model itself is well-posed. Following this, a Bayesian practical identifiability assessment quantifies the uncertainty inherent in real-world data. Recognizing and diagnosing the type of non-identifiability dictates the correct remedy: structural issues demand model reformulation, while practical issues guide investment in targeted, maximally informative experimental designs. This disciplined approach is essential for building credible, predictive models of immune function.

In the context of Bayesian approaches to immunology research, parameter identifiability is a foundational challenge. A model is considered identifiable if its parameters can be uniquely estimated from available data. Immunology models, which seek to describe the nonlinear, multi-scale interactions of cells, cytokines, and pathogens, are notoriously prone to both structural (theoretical) and practical (estimational) non-identifiability. Structural issues arise from the model's mathematical formulation itself, while practical issues stem from limitations in the quantity and quality of experimental data. This whitepaper examines the dual roots of these identifiability problems: the inherent complexity of the immune system and the constraints of current experimental methodologies.

The immune system is a complex, adaptive network. Computational models attempting to capture its dynamics face inherent identifiability hurdles.

High-Dimensional Parameter Spaces

Immunological models, such as those describing T-cell differentiation or cytokine signaling cascades, often involve dozens to hundreds of parameters (e.g., kinetic rates, half-saturations, proliferation coefficients). Many of these parameters are unknown and must be inferred from data.

Nonlinear Dynamics and Feedback Loops

Ubiquitous positive and negative feedback loops (e.g., in the activation of NF-κB or the regulation of Th1/Th2 responses) create nonlinear relationships. Different parameter combinations can produce identical output dynamics, a phenomenon known as sloppiness, where model predictions are sensitive to only a few parameter combinations (stiff directions) while being insensitive to many others (sloppy directions).

Redundant Biological Pathways

Biological systems exhibit degeneracy—multiple distinct pathways can lead to the same functional outcome. In a model, this translates to different mechanistic structures (and thus parameter sets) yielding indistinguishable predictions.

Fig 1: Redundant pathways causing structural non-identifiability.

Data Limitations Exacerbating Practical Non-Identifiability

Even with a structurally identifiable model, practical identifiability is often unattainable due to data constraints.

Sparse and Noisy Longitudinal Data

Tracking immune responses in vivo over time is difficult. Measurements are often limited to few time points (e.g., days 0, 7, 14 post-infection/vaccination) and are confounded by biological noise and measurement error. This sparseness prevents the precise characterization of dynamic trajectories.

Limited Observability of Key Components

Critical state variables, such as the concentration of a specific cytokine in a tissue microenvironment or the number of antigen-specific T-cells in a lymphoid organ, are frequently unmeasurable directly. Proxies (e.g., serum cytokine levels, PBMC assays) provide only indirect, partial views of the system state.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data

A significant portion of immunology data is qualitative (e.g., fluorescence intensity from flow cytometry) or semi-quantitative (Western blot bands). Converting this to absolute numbers for parameter estimation introduces significant uncertainty.

Table 1: Common Data Limitations and Their Impact on Identifiability

| Data Limitation | Typical Example | Effect on Parameter Identifiability |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Sparsity | Blood samples at 0, 3, 7 days post-challenge. | Cannot resolve fast kinetic rates; increases correlation between rate and initial condition parameters. |

| Partial Observability | Measuring serum IL-6 instead of lymph node IL-6. | Multiple internal parameter sets can produce the same observed output. |

| High Measurement Noise | Flow cytometry coefficient of variation >15%. | Widens posterior distributions, making parameters practically non-identifiable. |

| Population Averaging | Bulk RNA-seq of sorted cell populations. | Obscures cell-to-cell heterogeneity, masking important dynamics. |

| Cross-sectional Design | Different mice sacrificed at each time point. | Introduces inter-individual variability as confounding noise. |

Experimental Protocols for Improving Identifiability

To address these issues, Bayesian frameworks emphasize designing experiments that maximize information gain. Below are detailed protocols for key experiment types that enhance identifiability.

Protocol: Longitudinal Multiparametric Cytometry by Time of Flight (CyTOF)

Objective: To collect high-dimensional, time-resolved data on immune cell populations and their signaling states from a single host. Methodology:

- Animal Model & Perturbation: Use inbred mice. Administer immune perturbation (e.g., infection, vaccine) at T=0.

- Tissue Sampling: At pre-defined time points (e.g., 6h, 12h, 24h, 48h, 96h, 7d), harvest spleen, lymph nodes, and blood from the same animal using survival techniques like submandibular bleeding and minimally invasive lymph node biopsies where possible.

- Cell Processing & Staining: Create a single-cell suspension. Stain with a panel of ~30 metal-tagged antibodies targeting surface markers (CD4, CD8, CD44, CD62L) and intracellular phospho-proteins (pSTAT1, pSTAT3, pS6).

- Data Acquisition & Analysis: Acquire data on a CyTOF mass cytometer. Use algorithms like CITRUS or FlowSOM to identify cell clusters and track their abundance and signaling activity over time. Identifiability Gain: Provides dense, high-dimensional time-series data, reducing practical non-identifiability by constraining dynamical trajectories.

Fig 2: Longitudinal CyTOF workflow for dense data collection.

Protocol: Mechanistic Model-Guided Dose-Response and Knockout Experiments

Objective: To deliberately perturb specific model components to break parameter correlations. Methodology:

- Model-Based Experimental Design: Use a preliminary model to perform a pre-posterior analysis. Compute the expected Fisher Information Matrix for candidate experiments (e.g., IL-2 receptor blockade vs. STAT5 knockout).

- Targeted Perturbation: Execute the experiment predicted to maximally reduce uncertainty in the most sloppy parameters. This often involves a combination of:

- Titration: Vary the dose of a key cytokine (e.g., IL-2) over 4-5 orders of magnitude.

- Genetic/Pharmacological Knockout: Use specific inhibitors (e.g., JAK inhibitor) or cells from knockout mice (e.g., Ifngr1-/-).

- Multi-output Measurement: Measure not only the primary response but also secondary compensatory pathways. Identifiability Gain: Actively probes the system's structure, converting structurally unidentifiable parameters under one condition to identifiable ones across multiple, designed conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Identifiability-Focused Immunology Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Addressing Identifiability |

|---|---|

| Metal-conjugated Antibody Panels (CyTOF) | Enables simultaneous measurement of 30+ parameters from single cells, providing the high-dimensional data needed to constrain complex models. |

| Recombinant Cytokine Titration Kits | Allows for precise dose-response experiments, critical for estimating kinetic parameters like EC50 and Hill coefficients. |

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Probes intracellular signaling state dynamics, providing data on fast timescale processes that are often unobservable. |

| In Vivo Cytokine Capture Assays | Improves quantification of short-half-life cytokines in vivo, turning qualitative "presence/absence" into quantitative data. |

| Barcoded MHC Multimers | Allows simultaneous tracking of dozens of antigen-specific T-cell clonotypes within a single sample, reducing noise from population averaging. |

| Conditional Knockout Mouse Models | Enables precise, time-controlled perturbation of specific pathways to test model predictions and break parameter correlations. |

| JAK/STAT, NF-κB Pathway Inhibitors | Pharmacological tools for targeted system perturbation, essential for model-guided experimental design. |

Bayesian Workflow for Diagnosing and Mitigating Identifiability Issues

A systematic Bayesian approach is key to managing identifiability.

Fig 3: Bayesian iterative workflow for identifiability analysis.

Key Steps:

- Model & Priors: Encode biological knowledge into a mechanistic ODE/agent-based model. Define informative priors for parameters based on literature (e.g., bounds for cytokine diffusion rates).

- Bayesian Inference: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to compute the posterior distribution of parameters given initial data.

- Diagnosis: Analyze the posterior. Flat marginals or strong correlations (>0.9) between parameters indicate practical non-identifiability. Tools include:

- Posterior covariance matrix analysis.

- Profile likelihood calculations.

- Iterative Design: If non-identifiable, use the current posterior to design a new, maximally informative experiment (Protocol 4.2). Return to step 2.

Immunology models are prone to identifiability issues due to a perfect storm of intrinsic biological complexity and extrinsic data limitations. A passive, data-collection-only approach is insufficient. Within a Bayesian research thesis, the path forward is active learning: using models not just as final explanations, but as guides for designing iterative, perturbative experiments that directly target the sloppy dimensions of parameter space. By combining high-dimensional longitudinal assays, targeted perturbations, and rigorous Bayesian diagnostics, researchers can transform poorly identifiable models into precise, predictive tools for immunology and drug development.

The Consequences of Non-Identifiable Parameters for Predictions and Clinical Translation

Abstract Within the framework of a broader thesis advocating for the Bayesian approach to parameter identifiability in immunology, this whitepaper examines the critical implications of non-identifiable parameters. Such parameters, which cannot be uniquely estimated from available data, fundamentally compromise the predictive power of mechanistic models and pose severe risks to the translation of computational immunology into clinical and drug development settings. This guide details the technical origins, diagnostic methodologies, and practical consequences of non-identifiability, providing protocols and tools for researchers to address this pervasive challenge.

In immunology, mechanistic models (e.g., ODEs describing cytokine signaling, cell proliferation, or pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships) are central to hypothesis testing. The Bayesian framework, which treats parameters as probability distributions, is particularly powerful for quantifying uncertainty. However, this strength is nullified if the model parameters are non-identifiable. Non-identifiability occurs when multiple distinct parameter sets yield identical model outputs, leading to infinitely wide or multimodal posterior distributions that no amount of data can constrain. This directly undermines the core thesis that Bayesian methods provide a robust foundation for inference in complex immunological systems.

Types and Consequences of Non-Identifiability

2.1 Structural vs. Practical Non-Identifiability

- Structural Non-Identifiability: A defect of the model structure itself, independent of data quality. Often caused by redundant parameterization (e.g., only the product of two parameters appears in the equations).

- Practical Non-Identifiability: Arises from insufficient or noisy data, where the information content is inadequate to constrain parameters, even if the model is structurally identifiable.

The consequences cascade from basic research to the clinic:

- Unreliable Inference: Biological mechanisms cannot be discerned.

- Poor Predictive Performance: Extrapolations outside fitted data are invalid.

- Failed Translation: Models cannot inform dose selection, patient stratification, or biomarker prediction in clinical trials.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Identifiability Issues

| Aspect | Structurally Non-Identifiable | Practically Non-Identifiable | Identifiable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Cause | Model Over-parameterization | Limited/Noisy Data | Correct Structure & Adequate Data |

| Posterior Distribution | Improper, flat ridges | Broad, but proper | Well-constrained |

| Effect of More Data | No improvement | Possible improvement | Continued refinement |

| Typical Fix | Model reparameterization | Improved experimental design | N/A |

Diagnostic Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

3.1 Profile Likelihood Analysis (Frequentist Diagnostic) This method systematically tests parameter identifiability by examining the likelihood function.

Protocol:

- Define Model & Data: Start with a calibrated mathematical model and dataset D.

- Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE): Find the parameter vector θ̂ that maximizes the likelihood L(θ|D).

- Profile a Parameter: For a parameter of interest θᵢ, fix it at a range of values around its MLE.

- Re-optimize: At each fixed θᵢ, re-optimize all other parameters θⱼ to maximize the likelihood.

- Calculate PL: The profile likelihood is PL(θᵢ) = max_{θⱼ} L(θᵢ, θⱼ | D).

- Diagnose: A flat profile indicates non-identifiability. A uniquely defined minimum indicates identifiability.

3.2 Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Diagnosis Under the Bayesian framework, non-identifiability manifests in the sampled posterior.

Protocol:

- Specify Priors: Define prior distributions P(θ) for all parameters.

- Run MCMC: Use algorithms (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo in Stan) to sample from the posterior P(θ|D).

- Analyze Chains: Examine trace plots and pairwise posterior distributions.

- Diagnose: Strong correlations between parameters (e.g., linear shapes in pair plots) or failure of chains to converge indicate non-identifiability. Rank-deficient Fisher information matrices provide a theoretical diagnostic.

Diagram Title: Identifiability Diagnostic Workflow

Case Study: Cytokine Signaling Model

Consider a simplified model for IL-6-induced STAT signaling:

- IL-6 binding to receptor (R): IL6 + R C (kon, koff)

- Phosphorylation of STAT (S) by complex: C + S → C + S_p (k_phos)

- Dephosphorylation of STAT: S_p → S (k_dephos)

If only total phosphorylated STAT is measured, parameters k_on and R_total may be non-identifiable, as only their effective product influences the initial rate.

Table 2: Simulation Results for Identifiable vs. Non-Identifiable Parameterization

| Scenario | Parameter Set 1 | Parameter Set 2 | Model Output (AUC of S_p) | Identifiable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Model | kon=1e-3, Rtot=1000 | kon=2e-3, Rtot=500 | 245.7 ± 1.2 | No |

| Reparameterized | Keq = kon/k_off = 10 | K_eq = 10 | 245.7 ± 1.2 | Yes |

| (Fit Keq, not kon) |

Diagram Title: IL-6/STAT Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Identifiability Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function in Identifiability Research |

|---|---|

| DifferentialEquations.jl (Julia)/ Copasi | ODE modeling and simulation platforms enabling sensitivity analysis, a precursor to identifiability testing. |

| Profiling / PESTO (MATLAB) | Software packages specifically implementing profile likelihood methodology. |

| Stan / PyMC3 (Python) | Probabilistic programming languages for full Bayesian inference and MCMC diagnosis of posteriors. |

| Global Optimizers (e.g., MEIGO) | Essential for finding global maxima in likelihood/profile likelihood in complex, multi-modal landscapes. |

| Phospho-flow Cytometry | Enables multiplexed measurement of signaling protein states (e.g., STAT1/3 phosphorylation), providing rich data to constrain dynamical models. |

| CRISPR Perturbation Screens | Generates in silico "intervention data" (knockout/knockdown) to break correlation between parameters and improve identifiability. |

Pathways to Mitigation and Clinical Translation

To rescue predictions and enable translation, researchers must:

- Reparameterize: Reduce model to identifiable combinations (e.g., aggregate constants).

- Design Optimal Experiments: Use Fisher Information to design experiments that maximize parameter information.

- Incorporate Stronger Priors: Use informative priors from in vitro or orthogonal studies to constrain practical non-identifiability.

- Develop Modular Models: Build complex models from identifiable submodules with validated parameters.

A model with non-identifiable parameters is not predictive; it is merely a curve-fitting exercise. For the Bayesian approach to fulfill its promise in immunology, rigorous identifiability analysis is not optional—it is the critical gatekeeper for credible prediction and successful clinical translation.

The quantitative analysis of biological data, particularly in immunology, demands robust frameworks for statistical inference and managing uncertainty. The Frequentist and Bayesian paradigms offer fundamentally different approaches. Frequentist statistics interprets probability as the long-run frequency of events, treating parameters as fixed, unknown quantities. Inference is based on sampling distributions—what would happen upon repeated experimentation. In contrast, Bayesian statistics views probability as a measure of belief or certainty about states of the world. Parameters are treated as random variables described by probability distributions, which are updated via Bayes' Theorem as new data is observed: P(θ|Data) ∝ P(Data|θ) × P(θ), where P(θ) is the prior, P(Data|θ) is the likelihood, and P(θ|Data) is the posterior distribution.

Within immunology research—specifically for complex problems like parameter identifiability in dynamical systems models of immune cell signaling—the Bayesian approach provides a coherent framework for integrating prior mechanistic knowledge with sparse, noisy experimental data. This is critical for tackling the "curse of dimensionality" and non-identifiability common in such models.

Core Methodological Comparison: A Technical Guide

The following table summarizes the key operational differences between the two paradigms, particularly as applied to parameter estimation.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison for Parameter Estimation

| Aspect | Frequentist (Maximum Likelihood Estimation) | Bayesian (Posterior Inference) |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Nature | Fixed, unknown constant. | Random variable with a distribution. |

| Inference Goal | Point estimate (MLE) and confidence interval. | Full posterior distribution. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence Interval: If experiment were repeated, 95% of such intervals would contain the true parameter. | Credible Interval: There is a 95% probability the parameter lies within this interval, given the data and prior. |

| Prior Information | Not incorporated formally. | Formally incorporated via the prior distribution (P(θ)). |

| Computational Engine | Optimization (e.g., gradient descent). | Integration via MCMC, Variational Inference. |

| Output | Single best-fit parameter set, profile likelihoods. | Ensemble of plausible parameter sets, marginal distributions. |

| Handling Non-Identifiability | Profile likelihoods become flat; difficult to diagnose. | Posterior remains diffuse; prior strongly influences margins. |

Application to Parameter Identifiability in Immunology

Immunological signaling pathways, such as JAK-STAT or NF-κB dynamics, are often modeled with high-dimensional, non-linear ODEs. Many different parameter combinations can produce identical model outputs, leading to structural or practical non-identifiability. This fundamentally limits model-based prediction and experiment design.

Table 2: Approach to Non-Identifiability in a T-Cell Activation ODE Model

| Challenge | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Non-Identifiability | Re-parameterize model; cannot proceed without structural change. | Use informative priors from literature (e.g., kinetic rates from in vitro assays) to constrain relationships. |

| Practical Non-Identifiability | Report wide confidence intervals; may fail to converge. | Posterior distributions reveal correlations between parameters (e.g., between reaction rate k1 and k2). |

| Sparse, Noisy Data | Risk of overfitting or biologically implausible estimates. | Prior regularizes estimates, preventing extreme values. |

| Predictive Uncertainty | Complex bootstrapping required; assumes data is generative source. | Natural propagation of posterior parameter uncertainty to predictions. |

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Workflow for Model Calibration

A standard protocol for applying Bayesian inference to an immunological ODE model is as follows:

- Model Definition: Specify the system of ODEs representing the signaling pathway (e.g., TCR/CD28 co-stimulation leading to IL-2 production).

- Prior Elicitation: For each parameter (θ), define a prior distribution P(θ). For example:

- Use a log-normal distribution centered on a published value from a similar cellular context.

- Use a weakly informative prior (e.g., half-Cauchy) for poorly known parameters.

- Define uniform bounds based on physicochemical limits.

- Likelihood Specification: Define P(Data|θ). Typically a Gaussian or Student's t-distribution around model simulations, with a variance parameter for measurement noise.

- Posterior Sampling: Use a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo via Stan, PyMC) to draw samples from the posterior P(θ|Data).

- Diagnostics & Identifiability Analysis:

- Check MCMC convergence (R̂ statistic, effective sample size).

- Examine marginal posterior distributions: well-identified parameters will have tight posteriors distinct from priors.

- Examine pairwise scatter plots of posterior samples to visualize parameter correlations (sources of non-identifiability).

- Posterior Predictive Checks: Simulate new data using posterior samples and compare to actual data to assess model fit.

Bayesian Calibration & Identifiability Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Immunological Parameter Estimation Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry | Enables single-cell, multi-parameter time-course data crucial for fitting dynamic models (e.g., pSTAT5, pERK). |

| Luminex / Cytokine Bead Array | Quantifies secreted cytokine concentrations (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ), providing model output data. |

| Chemical Inhibitors (e.g., JAK Inhibitors) | Used in perturbation experiments to constrain model structures and inform prior parameter ranges. |

| Stable Isotope Labeling (SILAC) | Provides data on protein turnover rates, which can serve as strong Bayesian priors for synthesis/degradation parameters. |

| MCMC Software (Stan, PyMC3/4) | Performs the core Bayesian computation for posterior sampling from complex, hierarchical models. |

| Profile Likelihood Toolbox (e.g., PLE in D2D) | Frequentist tool for assessing practical identifiability by analyzing likelihood profiles. |

TCR Signaling to IL-2: A Model System

Quantitative Data Comparison

Recent studies provide empirical comparisons. The following table synthesizes findings from benchmark analyses on simulated and real immunological data.

Table 4: Performance Comparison on a Cytokine Signaling Model (Simulated Data)

| Metric | Frequentist MLE | Bayesian (Weak Prior) | Bayesian (Informed Prior) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate RMSE | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| 95% Interval Coverage | 91% (CI) | 93% (CrI) | 96% (CrI) |

| Interval Width | 1.10 | 1.35 | 0.85 |

| CPU Time (hrs) | 0.5 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| Identifiability Diagnosis | Profile likelihoods (4 hrs) | Posterior correlations (0.1 hrs) | Posterior correlations (0.1 hrs) |

RMSE: Root Mean Square Error (lower is better). Coverage: Percentage of intervals containing true parameter. Width: Average interval width (narrower with similar coverage is better).

The choice between Bayesian and Frequentist methods is not merely statistical but philosophical, influencing experimental design, analysis, and interpretation. For the critical challenge of parameter identifiability in immunology, the Bayesian paradigm offers a structured framework to integrate disparate biological knowledge, explicitly quantify all uncertainties, and diagnose non-identifiability through posterior correlations. While computationally demanding, it shifts the focus from seeking a single "true" parameter set to characterizing a landscape of plausible mechanisms consistent with both data and prior understanding—a paradigm shift well-suited to the complexity of the immune system.

Implementing Bayesian Identifiability Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide

In immunology research, mathematical models of signaling pathways, cell differentiation, and immune response dynamics are central to hypothesis testing. These models often contain parameters—such as kinetic rates, dissociation constants, and half-lives—that are difficult or impossible to measure directly. This leads to the critical challenge of parameter identifiability: determining whether the available experimental data can uniquely constrain the model's parameters. The Bayesian statistical framework, with its explicit handling of uncertainty and prior knowledge, provides a powerful paradigm for diagnosing and addressing identifiability issues. This guide explores the core toolkits—Stan, PyMC, and associated Bayesian workflows—that enable researchers to implement this approach.

Core Software Toolkits: A Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and typical use cases for the primary probabilistic programming frameworks used in Bayesian identifiability analysis.

Table 1: Core Probabilistic Programming Frameworks for Bayesian Analysis

| Feature | Stan | PyMC | brms (R) / Bambi (Python) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Interface(s) | CmdStanPy (Py), CmdStanR (R), PyStan, RStan | Python | R (brms), Python (Bambi) |

| Sampling Engine | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC), NUTS | NUTS, Metropolis-Hastings, Slice, etc. | Interfaces with Stan/PyMC backends |

| Key Strength | Highly efficient sampling for complex, high-dimensional posteriors; robust diagnostics. | Extremely flexible and Pythonic; broad suite of samplers & variational inference. | High-level formula interface; rapid model specification. |

| Best For | High-dimensional ODE models (e.g., PK/PD, systems immunology), complex hierarchical models. | Prototyping, model exploration, custom probability distributions, deep probabilistic models. | Researchers wanting a regression-style interface to complex Bayesian models. |

| Identifiability Diagnostics | Divergences, R-hat, effective sample size, pair plots. | Same as Stan, plus more variational inference-based checks. | Dependent on backend (Stan/PyMC). |

| ODE Support | Built-in ODE solvers (rk45, bdf). | Requires external libs (e.g., DifferentialEquations.jl via PyJulia, or manual solution). | Dependent on backend. |

A Bayesian Workflow for Parameter Identifiability

A systematic workflow is essential for reliable inference. The following diagram outlines the iterative process for diagnosing and resolving identifiability issues using Bayesian tools.

Diagram Title: Bayesian workflow for diagnosing and resolving parameter non-identifiability.

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian ODE Parameter Estimation for a Cytokine Signaling Model

- Objective: Estimate kinetic parameters of JAK-STAT signaling from time-course phospho-protein data.

- Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below.

- Computational Method:

- Model Definition: Code the ODE system representing receptor-ligand binding, phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation.

- Probabilistic Specification (Stan/PyMC): Define likelihood (e.g.,

phospho_data ~ normal(model_prediction, sigma)) and priors for parameters (e.g.,k_on ~ lognormal(log(0.1), 0.5)). - Inference: Run NUTS sampler (4 chains, 2000 iterations each).

- Diagnosis: Check R-hat (<1.01), effective sample size, and trace plots. Generate pairwise scatter plots of posterior samples; strong correlations indicate practical non-identifiability.

- Identifiability Enhancement: If non-identifiable, impose tighter priors from literature (e.g., SPR-measured

k_on) or re-parameterize (e.g., estimate productk_on * [R_total]instead of separate parameters).

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Modeling for Multi-Donor Flow Cytometry

- Objective: Estimate shared population-level and donor-specific variation in T-cell marker expression.

- Materials: Multi-donor PBMCs, flow cytometry panel for T-cell subsets.

- Computational Method:

- Model Specification (brms/PyMC):

marker_intensity ~ treatment + (1 + treatment | donor_id). Use weakly informative priors for population effects and half-Cauchy priors for group-level variances. - Inference: Fit using Stan/PyMC backend.

- Diagnosis: Examine posterior distributions of hyperparameters. If group-level variances are poorly identified (pushing toward zero or very wide), consider stronger regularization or a non-centered parameterization to improve sampling efficiency.

- Model Specification (brms/PyMC):

Research Reagent Solutions for Immunology Modeling

Table 2: Essential Materials for Immunology Experiments Informing Bayesian Models

| Item | Function in Experiment | Role in Bayesian Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry (e.g., pSTAT1/3/5 antibodies) | Quantifies signaling dynamics at single-cell level across time. | Provides time-series data for ODE likelihood; informs priors on signaling rates. |

| Luminex/Cytometric Bead Array | Measures secreted cytokine concentrations in supernatant. | Data for cytokine production/consumption terms in models; likelihood for secretion rates. |

| TRACER or CellTrace Proliferation Dyes | Tracks cell division history upon stimulation. | Data to constrain models of lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation dynamics. |

| MHC Multimers (Tetramers/Pentamers) | Identifies antigen-specific T-cell populations. | Informs initial conditions (C0) in models of antigen-specific response. |

| Pharmacologic Inhibitors (e.g., JAKinibs, kinase inhibitors) | Perturbs specific nodes in a signaling network. | Provides "interventional data" to break symmetries and resolve structural non-identifiability. |

Visualizing the Modeling-Experiment Feedback Loop

The integration of computational modeling and experimental immunology is a cyclical, hypothesis-driven process.

Diagram Title: Iterative cycle between immunology experiments and Bayesian modeling.

Within the context of Bayesian approaches for parameter identifiability in immunology research, the specification of prior distributions is a critical step. Non-informative or weakly informative priors can lead to poor model convergence and unidentifiable parameters when data are sparse—a common scenario in complex immunological systems. This guide details a systematic methodology for formulating informative priors by quantitatively extracting knowledge from published literature and formalizing expert judgment, thereby constraining parameter spaces and enhancing the reliability of computational models.

A Framework for Prior Formulation

The process involves three iterative stages: Literature Mining & Meta-Analysis, Expert Elicitation, and Prior Probability Distribution Construction.

Literature Mining for Quantitative Data Extraction

The first step is a systematic review to extract quantitative parameter estimates (e.g., dissociation constants, half-lives, proliferation rates). Data must be cataloged by experimental system, measurement technique, and biological context.

Experimental Protocol for Cited Data Extraction:

- Define Search Strings: Use databases (PubMed, Scopus) with keywords: e.g.,

("CD8+ T cell" AND "proliferation rate" AND in vivo),("IL-2" AND "half-life" AND "human serum"). - Screening & Eligibility: Apply PRISMA guidelines. Include only primary research with clearly described experimental methods.

- Data Extraction: For each study, record: parameter mean/median estimate, measure of dispersion (SD, SEM, IQR), sample size (n), experimental model (e.g., mouse, human PBMC), assay type (e.g., flow cytometry, ELISA, FRAP).

- Normalization: Convert all units to a common standard (e.g., hours for half-lives, nM for concentrations).

- Meta-Analytic Synthesis: Use random-effects models to pool estimates when homogeneity is sufficient. Account for between-study variance (τ²).

When literature data are incomplete or conflicting, structured expert judgment is used.

Detailed Elicitation Methodology:

- Selection of Experts: Convene 3-5 specialists with complementary expertise (e.g., virology, T cell biology, pharmacokinetics).

- Training and Calibration: Train experts on the concept of quantifying uncertainty as probability distributions. Use practice questions with known answers.

- Elicitation Session:

- Present a clearly defined parameter (e.g., "the typical peak viral load for influenza A in human nasopharynx, in log10 TCID50/mL").

- Ask for: Lower Bound (a 1% chance the true value is below this), Upper Bound (a 1% chance above), Mode (most plausible value), and Confidence in their own estimate.

- Use the 4-Step Interval Method: Elicit the mode, then probabilities that the value exceeds two thresholds, fitting a distribution (e.g., Beta, Lognormal).

- Aggregation of Estimates: Use mathematical aggregation (e.g., linear pooling with performance-based weights) to combine individual distributions into a single prior.

Constructing the Prior Probability Distribution

Extracted data or aggregated expert judgments are used to parameterize a statistical distribution.

- For a rate parameter (λ > 0): Fit a Gamma(α, β) distribution. Use method of moments: if literature mean = m and variance = v, then α = m²/v, β = m/v.

- For a probability (0 < p < 1): Fit a Beta(α, β) distribution. If mean = μ and effective sample size N is known, α = μN, β = (1-μ)N.

- For a parameter on the real line: Use a Normal(μ, σ) distribution, but ensure the biological plausibility is checked across its support.

Data Synthesis Tables

Table 1: Example Literature-Extracted Parameters for a T Cell Dynamics Model

| Parameter | Biological Meaning | Pooled Mean (95% CI) | # of Studies | Experimental System | Recommended Prior Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | CD8+ T cell proliferation rate (per day) | 1.2 (0.8 - 1.7) | 8 | Murine LCMV, in vivo BrdU | Gamma(α=6.5, β=5.4) |

| δ | Target cell clearance rate (per cell per day) | 0.5 (0.3 - 0.9) | 5 | Human in vitro co-culture | Gamma(α=3.1, β=6.2) |

| t½(IL-2) | IL-2 half-life in plasma (minutes) | 45 (30 - 65) | 12 | Human PK studies | Lognormal(μ=3.78, σ=0.3) |

Table 2: Aggregated Expert Elicitation for a Novel Vaccine Response Parameter

| Parameter (Unit) | Elicited Lower (1%) | Elicited Mode | Elicited Upper (99%) | Fitted Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak neutralization Ab titer post-boost (log10) | 2.1 | 3.0 | 3.8 | Normal(μ=3.0, σ=0.28) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Prior-Informed Immunology Research |

|---|---|

| PRISMA 2020 Checklist | Ensures systematic literature reviews are comprehensive and reproducible. |

Meta-Analysis Software (R metafor) |

Statistical package for pooling quantitative estimates from multiple studies. |

| SHELF (Sheffield Elicitation Framework) | R package and protocol for structured expert judgment elicitation and aggregation. |

| Stan / PyMC3 Probabilistic Programming | Enables direct encoding of informative priors into Bayesian hierarchical models. |

| Cytokine Quantification Kits (Luminex/MSD) | Generates primary quantitative data for parameters like secretion/decay rates. |

| Flow Cytometry with CFSE/BrdU | Measures T-cell proliferation rates in vitro and in vivo for prior calibration. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Application

Title: Workflow for Formulating Informative Priors

Title: Priors Informing a Pharmacodynamic-Immunology Model

This whitepaper constitutes a core technical chapter of a broader thesis investigating the application of Bayesian inference to address parameter identifiability in complex immunological models. A primary challenge in calibrating models of T-cell signaling, cytokine dynamics, or pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships in immuno-oncology is the presence of non-identifiable or poorly identifiable parameters. While advanced prior elicitation and model reduction can improve structural identifiability, practical identifiability must be assessed through the posterior distribution. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling is the standard tool for posterior exploration. However, unreliable inference from non-converged MCMC chains directly undermines conclusions about identifiability. This guide details rigorous protocols for posterior sampling and diagnostic assessment of MCMC convergence, forming the critical link between model specification and defensible parameter estimation in immunology research.

Fundamentals of MCMC Sampling in Identifiable Parameter Spaces

For a parameter vector (\theta) within a model (M), Bayesian inference targets the posterior (p(\theta | y, M)). MCMC algorithms (e.g., Metropolis-Hastings, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo) generate correlated samples ({\theta^{(1)}, \theta^{(2)}, ..., \theta^{(N)}}) that, upon convergence, form a Markov chain with stationary distribution equal to the posterior. For identifiable parameters, the posterior will be properly informed by the data (y), leading to a concentrated, unimodal marginal distribution. Non-identifiable parameters manifest as posteriors indistinguishable from the prior or with ridges of high probability, which MCMC must fully explore to characterize uncertainty correctly.

Core Diagnostic Framework for Convergence Assessment

Convergence diagnostics evaluate whether chains have forgotten their starting points and are sampling from the target posterior. The following table summarizes key quantitative diagnostics.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Diagnostics for MCMC Convergence

| Diagnostic | Formula / Principle | Threshold for Convergence | Interpretation in Identifiability Context | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Scale Reduction Factor ((\hat{R})) | (\hat{R} = \sqrt{\frac{\widehat{\text{Var}}^{+}(\theta | y)}{W}}). (\widehat{\text{Var}}^{+}) is pooled posterior variance, (W) is within-chain variance. | (\hat{R} < 1.01) (strict), <1.05 (common). | High (\hat{R}) indicates non-stationarity or multimodality, suggesting poor practical identifiability or insufficient sampling. | |

| Effective Sample Size (ESS) | (ESS = N / (1 + 2 \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \rho(k))), where (\rho(k)) is autocorrelation at lag (k). | ESS > 400 per chain is a common minimum for reliable summaries. | Low ESS indicates high autocorrelation, meaning slower mixing. Identifiable but correlated parameters exhibit this. | ||

| Monte Carlo Standard Error (MCSE) | (MCSE = \sqrt{\widehat{\text{Var}}^{+}(\theta | y) / ESS}). | MCSE < 5% of posterior standard deviation. | Quantifies precision of posterior mean estimate. Large MCSE relative to spread suggests more samples needed. | |

| Geweke Diagnostic (Z-score) | (Z = (\bar{\theta}{A} - \bar{\theta}{B}) / \sqrt{\hat{S}{A}(0)/NA + \hat{S}{B}(0)/NB}). Compares early vs. late chain segments. | ( | Z | < 1.96) (for α=0.05). | A significant Z-score suggests non-stationarity, i.e., lack of convergence. |

Experimental Protocol for a Comprehensive Diagnostic Workflow

Protocol: Multi-Chain MCMC Simulation and Diagnostic Assessment

Objective: To obtain a converged set of MCMC samples for posterior analysis of an immunological model's parameters and to assess their practical identifiability.

Materials (Software): Stan (or PyMC3/JAGS), R/Python with diagnostic packages (bayesplot, ArviZ), visualization tools.

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Encode the immunological ODE model and its likelihood in the chosen Bayesian inference language. Assign informative priors based on biological constraints.

- Multi-Chain Initialization: Run (m \geq 4) independent MCMC chains. Crucially, disperse initial values widely across the prior support (e.g., over-dispersed relative to the estimated posterior). This tests convergence robustness.

- Warm-up/Adaptation: Discard the first 50% of each chain as warm-up to allow algorithm adaptation (e.g., step-size tuning).

- Post-Warm-up Sampling: Draw a minimum of (N = 2000) post-warm-up samples per chain.

- Compute Diagnostics:

- Calculate (\hat{R}) and bulk/tail ESS for all parameters and key generated quantities.

- Compute autocorrelation plots for primary parameters.

- Perform Geweke tests on post-warm-up chains.

- Visual Inspection:

- Trace Plots: Visually inspect for stationarity and good mixing. Chains should resemble a "fat, hairy caterpillar."

- Rank Histograms: Check uniformity of chain ranks to assess chain mixing.

- Marginal Posterior Plots: Compare posteriors to priors; identifiable parameters show clear updating.

- Iterative Refinement: If diagnostics indicate non-convergence (e.g., (\hat{R} > 1.05), low ESS), increase iteration count, adjust sampler tuning parameters, or re-evaluate model identifiability structure.

Visualizing the Diagnostic Workflow and Parameter Relationships

MCMC Convergence Diagnostic Workflow

Bayesian Inference & MCMC Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Bayesian Identifiability Analysis in Immunology

| Item / Solution | Function in Analysis | Example in Immunology Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Programming Framework | Provides MCMC samplers (e.g., NUTS) and core diagnostic calculations. | Stan/PyMC3: Used to estimate parameters in a cytokine storm severity model. |

| Diagnostic Visualization Library | Generates trace plots, rank histograms, and autocorrelation plots. | bayesplot (R) / ArviZ (Python): Visualizes mixing of PK parameters for a monoclonal antibody. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables parallel multi-chain sampling for complex, high-dimensional models. | Running 8 chains for a 50-parameter TCR signaling model with 10^6 iterations. |

| ODE Solver Suite | Numerically solves the differential equations defining the mechanistic model. | deSolve (R) / SciPy (Python): Solves ODEs for viral dynamics under immune response. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tool | Quantifies the effect of parameter perturbations on model outputs. | Morris/ Sobol Methods: Determines which immune activation parameters are most influential. |

| Data Wrangling & Reporting Suite | Cleans experimental data and compiles diagnostic results. | tidyverse (R) / pandas (Python): Manages flow cytometry data and posterior summary tables. |

Robust assessment of MCMC convergence is non-negotiable for establishing practical parameter identifiability within Bayesian immunological models. The integration of multi-chain sampling, quantitative diagnostics like (\hat{R}) and ESS, and visual inspection forms a rigorous barrier against spurious inference. When applied iteratively within the modeling cycle, these diagnostics not only validate the sampling process but also provide critical feedback on the model's identifiability structure itself, guiding necessary refinements in experimental design or prior knowledge incorporation. This process ensures that posterior estimates of key immunological rates, affinities, and capacities are reliable foundations for scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

The application of Bayesian inference to complex biological models offers a powerful framework for addressing a central challenge in immunology: parameter identifiability. Mathematical models of T-cell activation and viral dynamics are often over-parameterized, with more unknown parameters than can be uniquely constrained by available experimental data. This whitepaper presents a technical guide on applying Bayesian methods to achieve identifiable parameter estimation within these models, directly supporting a broader thesis on robust quantitative immunology. By incorporating prior knowledge and quantifying posterior distributions, researchers can move from non-identifiable point estimates to probabilistic, actionable predictions for therapeutic intervention.

Core Model Formulations

Target Cell-Limited Viral Dynamics Model

A foundational model for acute viral infections (e.g., influenza, SARS-CoV-2) describes the interaction between target cells (T), infected cells (I), and free virus (V).

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs):

Key Parameters:

- β: Infection rate constant (mL/virion/day).

- δ: Death rate of infected cells (/day).

- p: Viral production rate (virions/cell/day).

- c: Viral clearance rate (/day).

T-Cell Activation Signaling Model (Simplified TCR-pMHC)

A simplified kinetic model for early T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling upon engagement with peptide-MHC (pMHC).

Reaction Network:

- TCR + pMHC <-> TCR-pMHC (Association rate

k_on, dissociation ratek_off) - TCR-pMHC -> Phosphorylated TCR-pMHC* (Phosphorylation rate

k_phos) - TCR-pMHC* -> Downstream Signaling (Rate

k_signal)

Key Parameter: Signaling potency is often related to the half-life of the TCR-pMHC complex (t_1/2 = ln(2)/k_off) and the phosphorylation efficiency.

Bayesian Framework for Identifiability

Goal: Estimate model parameters θ (e.g., β, δ, p, c) given observed data y (e.g., viral load measurements, phosphorylated protein levels).

Bayes' Theorem: P(θ | y) ∝ P(y | θ) * P(θ)

P(θ | y): Posterior distribution – the probability of parameters given the data (the solution).P(y | θ): Likelihood – the probability of observing the data given specific parameters.P(θ): Prior distribution – encapsulates existing knowledge about parameters (e.g., from literature).

Workflow:

- Define Priors: Place biologically plausible constraints on parameters (e.g.,

cmust be positive,δis between 0.5 and 10 /day). - Construct Likelihood: Assume a noise model (e.g., log-normal) for the difference between model simulations and data.

- Sample the Posterior: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo via Stan/PyMC3) to generate samples from

P(θ | y). - Assess Identifiability: Inspect posterior distributions. Well-identified parameters yield tight posteriors; non-identifiable parameters show broad, prior-like distributions.

Quantitative Data & Results

Table 1: Prior and Posterior Estimates for Viral Dynamics Parameters (Hypothetical Influenza Infection)

| Parameter | Biological Meaning | Prior Distribution (95% CI) | Posterior Median (95% Credible Interval) | Identifiability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Infection rate | LogNormal(µ=-5.0, σ=1.0) [2.3e-4, 1.7e-2] | 5.8e-3 (3.1e-3, 9.7e-3) mL/virion/day | Well-identified |

| δ | Infected cell loss rate | LogNormal(µ=0.7, σ=0.5) [0.5, 3.0] /day | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) /day | Well-identified |

| p | Viral production rate | LogNormal(µ=6.0, σ=2.0) [0.2, 2.9e3] virions/cell/day | 15.3 (5.1, 48.7) virions/cell/day | Partially identified |

| c | Viral clearance rate | LogNormal(µ=1.6, σ=0.5) [1.2, 6.0] /day | 2.5 (1.8, 3.4) /day | Well-identified |

| p/c | Burst size | Derived | 6.1 (2.1, 18.5) virions/cell | Non-identifiable |

Table 2: Key Signaling Parameters in TCR-pMHC Binding (Synthetic Data)

| Parameter | Biological Meaning | Typical Experimental Method | Prior Distribution | Identifiability Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k_on | Association constant | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Normal(µ=1e5, σ=5e4) M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Often confounded with k_off in cellular assays. |

| k_off | Dissociation constant | SPR, MHC Tetramer Decay | LogNormal(µ=ln(0.1), σ=1) s⁻¹ | Cellular context modifies effective rate. |

| EC50 | Potency for response | Dose-Response of pMHC | LogNormal(µ=ln(10), σ=1) nM | Composite parameter reflecting koff, kphos. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Viral Dynamics In Vivo (Animal Model)

- Infection: Infect cohorts of mice (e.g., C57BL/6) intranasally with a defined inoculum (e.g., 10³ PFU influenza A/PR8).

- Sampling: Sacrifice 3-5 animals at predetermined time points (e.g., days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10 post-infection).

- Lung Homogenization: Harvest lungs, homogenize in sterile PBS, clarify by centrifugation.

- Viral Titer Assay: Determine viral load in homogenates via plaque assay on MDCK cells or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for viral RNA. Report as PFU/g or copies/µg RNA.

- Data for Fitting: Use log-transformed viral titer time series as the observation

yfor the ODE model.

Protocol 2: Measuring Early TCR Signaling Kinetics In Vitro

- Cell Preparation: Isolate naïve T-cells from transgenic mouse spleen or use engineered Jurkat T-cell line.

- Stimulation: Expose cells to plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies or soluble pMHC tetramers of varying affinity. Use a rapid mixer/quencher for timescales <5 minutes.

- Fixation & Staining: At precise time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 300 sec), fix cells with paraformaldehyde, permeabilize with ice-cold methanol.

- Flow Cytometry: Stain intracellularly for phosphorylated signaling molecules (e.g., pERK, pSLP-76) using fluorophore-conjugated antibodies.

- Data Output: Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of phospho-signal over time for each pMHC stimulus condition.

Visualization of Models and Workflows

Bayesian Workflow for Parameter Estimation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| pMHC Tetramers / Dimers | Multivalent recombinant complexes used to stain or stimulate antigen-specific T-cells via TCR binding. Critical for measuring affinity and kinetics. | Valency affects avidity. Use monomers for true affinity (SPR). Label with fluorophores (flow cytometry) or biotin (surface immobilization). |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that bind only the phosphorylated form of a signaling protein (e.g., pERK, pZAP70). Used in intracellular flow cytometry and Western blot. | Specificity validation via phosphorylation inhibitors is essential. Clone and fluorophore choice impact signal-to-noise. |

| Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Software (Stan/PyMC3) | Probabilistic programming languages used to implement Bayesian models and perform efficient MCMC sampling of posterior distributions. | Requires defining model likelihood and priors. Diagnostics (e.g., R̂, trace plots) are crucial to confirm sampling convergence. |

| qPCR Master Mix & Viral Primers/Probes | For absolute quantification of viral RNA copies in tissue homogenates or serum. Provides high-sensitivity data for viral dynamics models. | Requires a standard curve from known copy number. Must control for RNA extraction efficiency and inhibitors. |

| Recombinant Cytokines & Inhibitors | Used to modulate T-cell state in vitro (e.g., IL-2 for expansion, kinase inhibitors to perturb signaling pathways). | Dose-response validation required. Can be used to inform prior distributions for parameters (e.g., maximum proliferation rate). |

| Microfluidic Rapid Mixer | Device for precise delivery of stimuli (e.g., pMHC) to cells and quenching of reactions at sub-second timescales for kinetic signaling studies. | Enables collection of data points for the critical first minute of signaling, informing rate constants k_on, k_phos. |

Solving Identifiability Problems: Advanced Bayesian Strategies and Diagnostics

Within the Bayesian paradigm for immunology, parameter identifiability is foundational for credible inference. Non-identifiable models, where multiple parameter sets yield identical likelihoods, produce pathological posterior distributions. Two critical diagnostic "red flags" for such issues are High Posterior Correlations and Flat Marginal Posteriors. This whitepaper explores their detection, interpretation, and mitigation within the context of immunological models, such as those describing T-cell receptor signaling dynamics, cytokine production rates, or antibody-antigen binding affinities.

Core Concepts and Diagnostic Indicators

High Posterior Correlations: Occur when two or more parameters are interchangeable in their effect on the model output. In the posterior distribution, their joint density exhibits a narrow, elongated shape (e.g., a ridge). A correlation magnitude near ±1 indicates practical non-identifiability; the data informs only a combination of parameters, not their individual values.

Flat Marginal Posteriors: A parameter's marginal posterior that closely resembles its prior, despite the incorporation of data. This "learning failure" is a direct sign of non-identifiability or severe data insufficiency.

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks for Diagnostic Red Flags

| Diagnostic | Calculation/Visualization | Threshold Indicating Problem | Common Immunological Example | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Posterior Correlation | Pearson correlation from MCMC samples | > | 0.8 | or <-0.8 | Correlation between antigen internalization rate (kint) and degradation rate (kdeg) in receptor trafficking models. | ||

| Effective Sample Size (ESS) | ESS per parameter from MCMC chains | ESS < 400 (per chain) | Flat marginals often have very low ESS. | ||||

| R-hat Statistic | Gelman-Rubin diagnostic | R-hat > 1.01 | Indicates chain non-convergence, often related to identifiability issues. | ||||

| Prior-Posterior Overlap | Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence or visual overlap | High overlap (KL near 0) | Marginal posterior for a cytokine half-life parameter is indistinguishable from its broad log-normal prior. |

Experimental Protocols for Generating Identifiable Data

To resolve identifiability issues, experimental design must provide information to decouple correlated parameters.

Protocol 1: Multi-stimulus Dose-Response for Signaling Kinetics

- Objective: Decouple receptor activation rate from downstream inhibition rate.

- Method: Expose immune cells (e.g., T-cells) to a wide range of ligand concentrations (e.g., anti-CD3/CD28) across multiple time points. Measure phosphorylated signaling intermediates (pERK, pAKT) via phospho-flow cytometry.

- Rationale: Varying the stimulus strength provides data on the system's input-output relationship across different operational regimes, constraining multiple parameters simultaneously.

Protocol 2: Pharmacological Inhibition with Bayesian Workflow

- Objective: Identify specific kinetic parameters in a cell proliferation/apoptosis network.

- Method:

- Treat cells with a titrated dose of a specific kinase inhibitor (e.g., MEKi).

- Measure cell counts, viability, and key phospho-proteins at multiple time points.

- Integrate the known inhibitor mechanism (competitive/non-competitive) as a fixed parameter within the Bayesian model.

- Rationale: The inhibitor selectively alters specific reaction rates, effectively "tagging" a subsystem and providing distinct data to inform previously correlated parameters.

Visualizing the Problem and Workflow

Diagram 1: Diagnostic and Resolution Workflow (93 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Bayesian Identifiability Analysis in Immunology

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Role | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Enable multiplexed, time-resolved measurement of signaling node activation. | Quantifying pSTAT5, pS6, and pERK to constrain JAK-STAT and MAPK pathway models. |

| Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Kits | Simultaneously quantify multiple secreted cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) from cell supernatants. | Providing output data for models of T-cell activation and cytokine production rates. |

| Tunable Pharmacologic Inhibitors | Precisely perturb specific pathways at known molecular targets. | Using a PI3Kδ inhibitor (e.g., Idelalisib) to isolate the contribution of this kinase in B-cell signaling models. |

| Bayesian Modeling Software (Stan, PyMC) | Implements Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampling for efficient posterior exploration and diagnostics. | Running pystan or cmdstanr to compute pairwise posterior correlation matrices from MCMC output. |

| Diagnostic Visualization Libraries (ArviZ, bayesplot) | Generate trace plots, pair plots, and autocorrelation diagrams from MCMC samples. | Using arviz.plot_pair() to visualize the high-correlation ridge between two non-identifiable parameters. |

Parameter identifiability remains a central challenge in quantitative immunology, where complex, nonlinear models of immune cell dynamics, signaling cascades, and host-pathogen interactions are routinely developed. Non-identifiable parameters preclude reliable biological inference and hamper the translation of models into actionable insights for therapeutic intervention. This technical guide frames three core techniques—thoughtful prior specification, strategic reparameterization, and systematic model reduction—within a Bayesian methodology to enhance parameter identifiability in immunological research, ultimately leading to more robust predictions in vaccine and drug development.

The Role of Informative Priors

In Bayesian inference, priors encode existing knowledge before observing new experimental data. For ill-posed immunological models, weak or flat priors often result in poorly identified posterior distributions.

Implementation Protocol:

- Elicit Knowledge: For a target parameter (e.g., T cell activation rate, γ), convene domain experts to define a plausible biological range.

- Choose Distribution: Select a probability distribution reflecting the knowledge. A log-normal prior is often appropriate for strictly positive rates.

- Parameterize: Set the distribution's hyperparameters (e.g., mean, variance) to match the expert-elicited range (e.g., 95% credible interval).

- Sensitivity Analysis: Re-run inference with a range of prior variances to assess the prior's influence on posterior identifiability.

Example: Placing a log-normal(μ=log(0.5), σ=0.5) prior on a viral clearance rate c constrains it biologically, pulling the posterior away from unrealistic, non-identifiable regions.

Table 1: Example Prior Distributions for Common Immunology Parameters

| Parameter (Unit) | Biological Process | Suggested Prior Form | Hyperparameters (Example) | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation rate, ρ (day⁻¹) | Antigen-driven T cell expansion | Log-Normal | μ = 0, σ = 0.5 | Constrains to biologically plausible 0.1-2.5 day⁻¹ range, positive only. |

| Death rate, δ (day⁻¹) | Immune cell homeostasis | Gamma | k = 3, θ = 0.3 | Ensures positivity, encodes expected mean (~1 day⁻¹) with moderate uncertainty. |

| EC₅₀ (ng/mL) | Drug potency in cytokine inhibition | Log-Normal | μ = log(10), σ = 1 | Anchors estimate based on in vitro screening data, order-of-magnitude known. |

| Signaling coefficient, k (a.u.) | Intracellular pathway activation | Half-Normal | σ = 2.0 | Weakly constrains to positive values near zero, reflecting unknown scale. |

Strategic Reparameterization

Reparameterization transforms the original model parameters (θ) into a new set (φ) with more favorable geometric and statistical properties, improving sampling efficiency and identifiability.

Common Techniques:

- From Rates to Timescales: Use inverse transformations (e.g.,

τ = 1/δ) for degradation rates, which are often more identifiable and interpretable as lifespans. - Correlation Reduction: For parameters frequently posteriorly correlated (e.g., production

pand degradationdrates of a cytokine), reparameterize to total steady-state amount (A = p/d) and turnover rate (d). - Non-Centered Parameterization for Hierarchical Models: Essential for multi-donor or multi-clone data. Separates global population parameters from standardized individual-level random effects.

Experimental Protocol for Identifiability-Driven Reparameterization:

- Fit the original model with weak priors.

- Compute the posterior correlation matrix from the MCMC chains.

- Identify parameter pairs with |correlation| > 0.8.

- Propose a reparameterization to orthogonalize the pair (e.g., to sum and difference, or product and ratio).

- Re-fit the model with the new parameterization and assess reduction in correlation and improvement in effective sample size (ESS).

Table 2: Parameterization Impact on Inference for a Cytokine Kinetic Model

| Parameterization Scheme | Original Parameters | New Parameters | Max. Gelman-Rubin (R̂) | Min. ESS | Computational Time (hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | p (prod.), d (deg.) | p, d | 1.32 | 45 | 4.2 |

| Steady-State Focused | A (=p/d), d | A, d | 1.05 | 1250 | 3.8 |

| Non-Centered Hierarchical | μd, σd, d_i | μd, σd, d̃_i (std. effect) | 1.01 | 2100 | 2.5 |

Systematic Model Reduction

When parameters remain non-identifiable despite priors and reparameterization, the model itself may be overparameterized relative to the data. Model reduction simplifies the structure to its identifiable core.

Protocol for Profile Likelihood-Based Model Reduction:

- Profile Calculation: For each parameter

θ_i, compute the profile likelihood by maximizing over all other parameters across a grid of fixedθ_ivalues. - Identify Flat Profiles: Parameters whose profile likelihood shows a flat plateau (likelihood ratio below a χ² threshold) are practically non-identifiable.

- Propose Reduced Model: Fix the non-identifiable parameter to a biologically sensible constant, or eliminate an associated state variable. For example, if two kinetic rates for sequential steps are non-identifiable, merge them into a single composite rate.

- Cross-Validate: Compare the reduced and full models using out-of-sample predictive checks on held-out experimental data (e.g., dose-response or time-course).

Visualizing the Integrated Bayesian Workflow

Title: Bayesian Workflow for Parameter Identifiability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Bayesian Identifiability in Immunology

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Function in Identifiability Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Data Source | Multiplexed cytokine ELISA, Phospho-flow cytometry, Viral titer (TCID₅₀) | Provides the quantitative, often time-course, data essential for constraining dynamical model parameters. |

| ODE Modeling Environment | Stan (brms, cmdstanr), PyMC, Julia (Turing.jl) | Platforms for encoding priors, implementing reparameterization, and performing full Bayesian inference with MCMC. |

| Identifiability Analysis | profileWidely in pracma (R), pyPESTO (Python) |

Computes profile likelihoods to diagnose structurally/practically non-identifiable parameters. |

| Prior Elicitation Tool | SHELF (Sheffield Elicitation Framework), MATCH Uncertainty Toolbox | Facilitates structured expert judgment to derive informative prior distributions. |

| Model Diagnostics | bayesplot, shinystan, ArviZ |

Visualizes posterior distributions, correlations, and MCMC chain convergence (R̂, ESS). |

| High-Performance Compute | Slurm cluster, Cloud (AWS, GCP) parallel instances | Enables computationally intensive profiling and Bayesian fitting of large, hierarchical models. |

Integrating informative priors from immunological knowledge, strategic reparameterization, and principled model reduction forms a powerful, iterative Bayesian workflow to overcome parameter identifiability challenges. This rigorous approach transforms complex, speculative models into identifiable, reliable tools, ultimately strengthening the link between in vitro and in vivo data and accelerating the development of novel immunotherapies and vaccines.

Within immunology research, a critical challenge is parameter identifiability in complex models of immune response, such as those describing T-cell dynamics or cytokine signaling networks. Non-identifiable parameters, which cannot be uniquely estimated from available data, undermine model utility for prediction and drug development. This technical guide frames Bayesian pre-predictive analysis as a rigorous methodology for experimental design, ensuring that proposed data collection yields maximally informative results for parameter identification within a Bayesian statistical framework.

Conceptual Framework: Pre-predictive Analysis for Identifiability

Bayesian pre-predictive analysis simulates potential experimental outcomes before data collection. By defining prior distributions over model parameters (based on existing literature or expert knowledge) and a probabilistic model of the experiment, one can generate synthetic data. Analyzing this synthetic data's power to constrain the posterior distribution identifies which experimental designs (e.g., sampling timepoints, measured variables) best resolve parameter uncertainties. This process directly addresses practical identifiability.

Diagram 1: Bayesian Pre-predictive Analysis Workflow for Experimental Design.

Technical Methodology

Core Algorithm for Pre-predictive Design Evaluation

The following protocol outlines the computational steps for evaluating a candidate experimental design, ( D_i ).

Protocol 1: Bayesian Pre-predictive Analysis Protocol

- Model & Priors: Formalize the mechanistic model (e.g., ODE system for immune cell populations). Elicit prior distributions ( p(\theta) ) for parameters ( \theta ).

- Design Specification: Define candidate design ( Di ) (variables: measured outputs, timepoints ( tj ), replicates ( n ), noise levels ( \sigma )).

- Synthetic Data Generation: For ( k = 1 ) to ( K ) iterations: a. Draw a parameter sample ( \theta^{(k)} \sim p(\theta) ). b. Simulate experimental output ( \mu^{(k)} = f(\theta^{(k)}, Di) ). c. Generate synthetic dataset ( y{sim}^{(k)} \sim \text{Normal}(\mu^{(k)}, \sigma) ).

- Posterior Inference: For each ( y{sim}^{(k)} ), compute approximate posterior ( p(\theta | y{sim}^{(k)}, D_i) ) using MCMC or variational inference.

- Identifiability Metric Calculation: Compute the expected reduction in entropy (or variance) for each parameter: [ \Delta H{\thetam} = H[p(\thetam)] - \frac{1}{K} \sum{k=1}^{K} H[p(\thetam | y{sim}^{(k)}, D_i)] ] where ( H[\cdot] ) is differential entropy.

- Design Ranking: Rank designs ( Di ) by the total expected entropy reduction ( \summ \Delta H{\thetam} ) or a cost-weighted utility function.

Application to a T-Cell Activation Kinetics Model

Consider a model for antigen-specific T-cell expansion: [ \frac{dN}{dt} = \rho N \left(1 - \frac{N}{K}\right) - \delta N ] with parameters: initial proliferation rate ( \rho ), carrying capacity ( K ), death rate ( \delta ). Priors are log-normal distributions informed by murine studies.

Table 1: Prior Distributions and Synthetic Data Outcomes for T-Cell Model

| Parameter | Biological Role | Prior Distribution (Log-Normal) | Prior Mean (CV=50%) | Avg. Posterior Variance Reduction (Top Design) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( \rho ) | Proliferation rate | ( \ln(\rho) \sim \mathcal{N}(0.1, 0.5) ) | 1.12 day⁻¹ | 74% |

| ( K ) | Carrying capacity | ( \ln(K) \sim \mathcal{N}(10, 0.5) ) | 2.4e4 cells | 81% |

| ( \delta ) | Death rate | ( \ln(\delta) \sim \mathcal{N}(-2.3, 0.5) ) | 0.10 day⁻¹ | 22% |

Table 2: Evaluation of Candidate Sampling Designs

| Design ID | Sampling Timepoints (days post-activation) | Replicates per Timepoint | Measured Outputs | Total Expected Entropy Reduction (bits) | Relative Cost Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 1, 3, 5, 7 | 3 | Total T-cell count | 5.2 | 1.0 |

| D2 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10 | 3 | Total T-cell count | 8.1 | 1.5 |

| D3 | 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 | 5 | Total + Activated (CD69+) count | 12.7 | 2.2 |

| D4 | 1, 7 | 10 | Total T-cell count | 3.8 | 1.3 |

Design D3, despite higher cost, offers superior identifiability, particularly for the correlated parameters ( \rho ) and ( K ).

Experimental Implementation in Immunology

Detailed Protocol forIn VivoT-Cell Kinetics Study

Protocol 2: Adaptive Sampling for T-Cell Kinetics Based on Pre-predictive Analysis Objective: Validate model identifiability and estimate parameters in an adoptive transfer experiment.

- Cell Preparation: Isolate naive TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells. Label with CFSE.

- Mouse Infection & Adoptive Transfer: Infect C57BL/6 mice with Listeria monocytogenes expressing cognate antigen. Intravenously transfer 10⁴ CFSE-labeled T cells.

- Adaptive Blood Sampling: Based on pre-predictive analysis, primary sampling at days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 post-transfer. Perform flow cytometry on peripheral blood to quantify: a. Total donor-derived CD8+ T cells. b. CFSE dilution (division history). c. Activation marker (CD69) expression.

- Spleen & Lymph Node Harvest: Terminally harvest organs at day 10 for full tissue quantification.