Beyond CRP and ESR: Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices as Next-Generation Biomarkers in Autoimmunity and Oncology

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of novel systemic inflammatory indices, such as the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), Pan-Immune-Inflammation Value (PIV), and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), and their advantages over traditional...

Beyond CRP and ESR: Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices as Next-Generation Biomarkers in Autoimmunity and Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of novel systemic inflammatory indices, such as the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), Pan-Immune-Inflammation Value (PIV), and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), and their advantages over traditional markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational pathophysiology of these indices, their methodological applications in clinical trials and therapeutic monitoring, strategies to overcome current limitations, and rigorous validation against established benchmarks. By synthesizing evidence from autoimmune disorders and oncology, this review aims to inform the integration of these cost-effective, accessible tools into precision medicine and accelerated drug development pathways.

The New Landscape of Inflammation: Defining Novel Indices and Their Pathophysiological Basis

In the evolving landscape of medical diagnostics, systemic inflammatory indices derived from routine complete blood count (CBC) parameters have emerged as powerful tools for risk stratification and prognosis across diverse disease states. While traditional markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) have long been clinical mainstays, a new generation of composite indices—including the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI), and Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV)—offer enhanced prognostic capability by integrating multiple cellular components of the immune response. These indices reflect the complex interplay between inflammation, immunity, and disease pathogenesis, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the systemic inflammatory state than single-parameter measurements. Their calculation from routine CBC parameters makes them particularly valuable as cost-effective, readily accessible biomarkers with growing applications in oncology, cardiology, neurology, and beyond. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these novel indices, detailing their formulations, experimental protocols, and clinical performance data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Index Formulations and Calculation Methods

The novel systemic inflammatory indices integrate various cellular components of the peripheral immune response using distinct mathematical formulas. The calculation methodologies for these indices are standardized, leveraging absolute cell counts obtained from routine complete blood count analyses with differentials.

Formulas:

- SII = (Platelet count × Neutrophil count) / Lymphocyte count [1] [2] [3]

- SIRI = (Monocyte count × Neutrophil count) / Lymphocyte count [1] [4] [5]

- PIV = (Neutrophil count × Platelet count × Monocyte count) / Lymphocyte count [1] [4] [6]

- NLR = Neutrophil count / Lymphocyte count [1] [5] [6]

- IPI = (High-sensitivity CRP × NLR) / Albumin [1]

Table 1: Composition of Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices

| Index | Formula | Cellular Components Integrated | Physiological Processes Reflected |

|---|---|---|---|

| SII | (P × N)/L | Platelets, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes | Inflammation, immune response, thrombogenesis |

| SIRI | (M × N)/L | Monocytes, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes | Innate immune activation, inflammatory response |

| PIV | (N × P × M)/L | Neutrophils, Platelets, Monocytes, Lymphocytes | Pan-immune activation, systemic inflammation |

| NLR | N/L | Neutrophils, Lymphocytes | Inflammation-to-immunity balance |

| IPI | (Hs-CRP × NLR)/Albumin | Inflammation markers + nutritional status | Inflammation, nutritional status, acute phase response |

All cell counts are expressed as absolute numbers (typically ×10â¹/L). Blood samples should be collected in EDTA tubes and analyzed within established stability windows for each parameter (generally within 24 hours of collection) using automated hematology analyzers. The indices are unitless, with higher values typically indicating greater systemic inflammation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Blood Collection and Processing Protocol

Standardized protocols for sample collection and processing are essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible inflammatory index values across studies. The following methodology represents a consensus approach derived from multiple cited studies:

Sample Collection: Venous blood samples are collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes via venipuncture following standard phlebotomy procedures. For preoperative or baseline assessment, samples should be obtained within 24 hours prior to the procedure or intervention [6] [7]. For monitoring dynamic changes, consistent timing of follow-up samples is critical (e.g., day 7 post-intervention) [1].

Sample Processing: Blood samples should be analyzed within 30 minutes to 2 hours of collection to ensure cell count stability. Automated hematology analyzers (e.g., Sysmex XN-3000, Mindray BC-6800, or Beckman Coulter UniCel DxH 800 systems) are used for complete blood count with differential analysis [6]. Laboratories should establish and validate quality control procedures according to standardized protocols.

Data Extraction: The following parameters are recorded from the CBC with differential: absolute neutrophil count (×10â¹/L), absolute lymphocyte count (×10â¹/L), absolute monocyte count (×10â¹/L), and absolute platelet count (×10â¹/L). For calculation of the Inflammation Prognostic Index (IPI), high-sensitivity CRP (mg/L) and albumin (g/dL) levels are additionally required [1].

Index Calculation: Each index is calculated according to its standard formula using the absolute cell counts. Some studies apply log-transformation to normalized skewed distributions before statistical analysis [1]. For longitudinal studies, fold change between timepoints can be calculated as T2/T1.

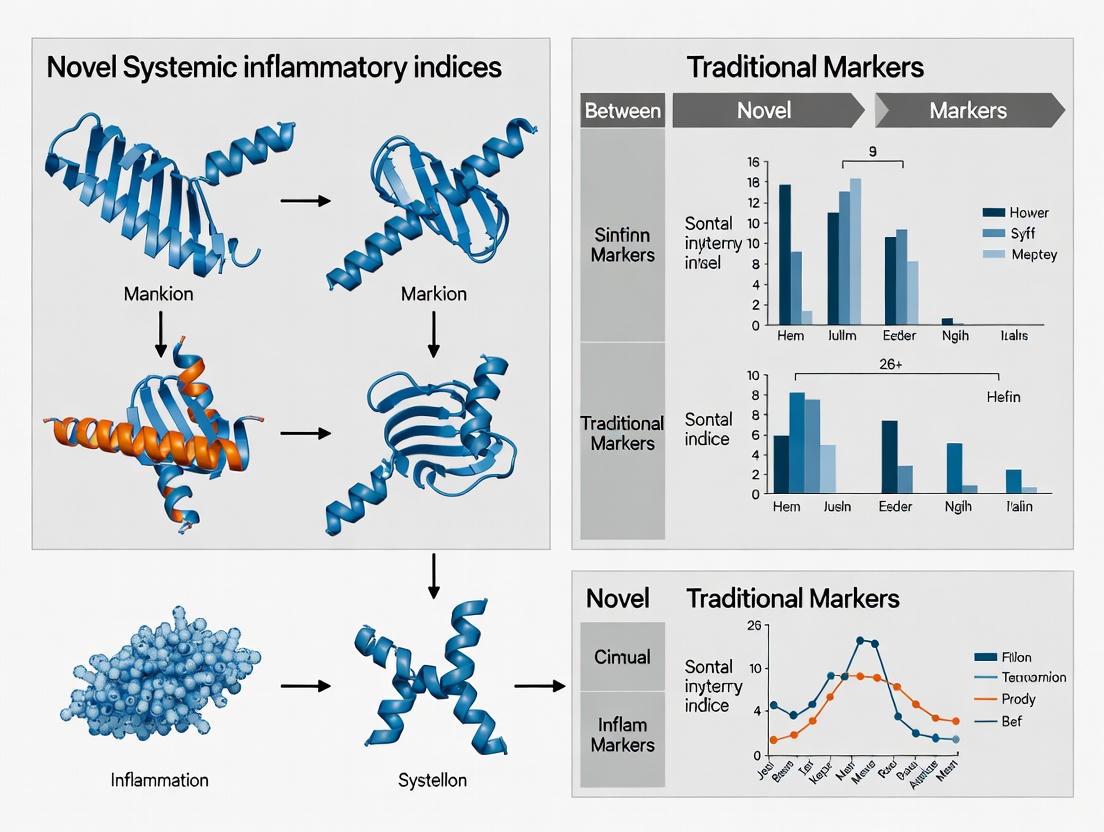

Research Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for calculating and applying novel systemic inflammatory indices in clinical research:

Comparative Performance Data Across Disease States

Prognostic Performance in Oncology

In clinical oncology, novel inflammatory indices have demonstrated significant prognostic value for survival outcomes across multiple cancer types, often outperforming traditional markers.

Table 2: Prognostic Performance of Inflammatory Indices in Oncology

| Cancer Type | Index | Outcome Measure | Effect Size (HR/OR) | AUC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | SII | Overall Survival | HR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.51-2.33 | - | [2] |

| Breast Cancer | SII | Disease-Free Survival | HR=2.10, 95% CI: 1.60-2.75 | - | [2] |

| Breast Cancer | SII | Diagnosis | OR=1.44 (Q4 vs Q1) | 0.816 | [3] |

| Early-Stage NSCLC | PIV | Disease-Free Survival | 101.2 vs 109.8 months (p=0.003) | - | [6] |

| Early-Stage NSCLC | NLR | Overall Survival | 102.7 vs 109.4 months (p=0.040) | - | [6] |

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 28 studies confirmed that elevated SII was significantly associated with worse overall survival (HR=1.88), disease-free survival (HR=2.10), and distant metastasis-free survival (HR=1.89) in breast cancer patients [2]. In early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), patients with high PIV showed significantly worse disease-free survival (101.2 vs. 109.8 months, p=0.003) [6].

Predictive Value in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases

In acute neurological and cardiovascular conditions, these indices provide valuable insights for risk stratification and outcome prediction.

Table 3: Performance in Neurological and Cardiovascular Conditions

| Condition | Index | Population | Key Findings | AUC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Ischemic Stroke | SIRI | Post-thrombolysis | Independent predictor of 3-month outcomes | >0.600 | [1] |

| Acute Ischemic Stroke | IPI | Post-thrombolysis | Best predictive value for 3-month outcomes | >0.600 | [1] |

| Peripheral Vertigo | SIRI | Diagnosis | Higher in patients vs controls (1.50 vs 0.77) | 0.760 | [4] |

| Peripheral Vertigo | PIV | Diagnosis | Higher in patients vs controls (393.59 vs 184.21) | - | [4] |

| Lead Extraction | SII/PIV | Complication prediction | No significant association with complications | NS | [7] |

In acute ischemic stroke patients receiving thrombolysis, SIRI, IPI, and PIV at day 7 post-treatment and their dynamic changes were independent predictors of 3-month functional outcomes, with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis showing moderate discrimination (AUC >0.600) [1]. For peripheral vertigo diagnosis, SIRI demonstrated an AUC of 0.760 with 82.3% sensitivity and 60.3% specificity at the optimal cutoff [4].

Performance in Other Inflammatory Conditions

The utility of these indices extends to other inflammatory conditions including pancreatic disease and psychiatric disorders.

In hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis (HTG-AP), SII and SIRI significantly increased with disease severity. In fully adjusted models, the highest tertile of SII demonstrated a 3.12-fold increased risk of moderate-severe or severe pancreatitis compared to the lowest tertile [5]. ROC analysis showed SII had an AUC of 0.666 for predicting disease severity in this population [5].

In bipolar disorder, both PIV and SII were significantly elevated during manic episodes compared to healthy controls (PIV: 405.11±266.83 vs. 243.55±150.96, p<0.001; SII: 551.84±295.12 vs. 423.26±171.95, p=0.002) [8]. PIV showed potential for distinguishing manic episodes from other mood states in bipolar disorder.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Inflammatory Index Studies

| Item | Specification | Research Function | Example Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | K2EDTA or K3EDTA, 3-5mL | Plasma preservation for hematological analysis | Standard venipuncture; invert 8-10 times immediately after collection [6] |

| Automated Hematology Analyzer | Sysmex XN-3000, Mindray BC-6800, or Beckman Coulter UniCel DxH 800 | Complete blood count with differential analysis | Calibration according to manufacturer specifications; daily quality control [6] |

| Clinical Data Management System | Electronic health record integration | Covariate data collection and management | Extraction of demographic, clinical, and outcome variables [1] [5] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R, SPSS, Review Manager | Data analysis and visualization | ROC analysis, logistic regression, survival analysis [1] [2] |

| Pamicogrel | Pamicogrel, CAS:101001-34-7, MF:C25H24N2O4S, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Pioglitazone Hydrochloride | Pioglitazone Hydrochloride, CAS:112529-15-4, MF:C19H21ClN2O3S, MW:392.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Advantages and Clinical Applications

The novel systemic inflammatory indices offer distinct advantages over traditional markers. Their composite nature allows for a more integrated assessment of the immune-inflammatory response by capturing interactions between different cellular pathways. The SII simultaneously reflects inflammatory status (through neutrophils), immune response (through lymphocytes), and thrombotic tendency (through platelets) [2] [3]. The PIV provides an even more comprehensive assessment by incorporating monocytes, which play crucial roles in both inflammation and immune regulation [6] [8].

These indices have demonstrated particular clinical value in several domains. In oncology, they contribute to prognostic stratification and may help identify patients who could benefit from more aggressive treatment or closer monitoring [2] [6]. In acute care settings such as stroke and pancreatitis, they aid in early risk stratification and monitoring of treatment response [1] [5]. For drug development, these indices offer cost-effective biomarkers for assessing inflammatory components of disease pathophysiology and treatment effects.

The limitations of these indices primarily relate to their non-specific nature, as they can be influenced by various conditions including infections, stress, and non-target inflammatory states. Additionally, optimal cut-off values may vary across populations and disease states, requiring local validation [2] [7]. Despite these limitations, their accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and proven prognostic value support their continued investigation and clinical application across diverse medical specialties.

In the evolving landscape of biomedical research, the quest for precise prognostic tools has led to a shift from traditional, single-marker approaches toward novel systemic inflammatory indices. These composite formulas, derived from routine complete blood count parameters, offer a more holistic view of the host's immune and inflammatory status, providing critical insights into disease prognosis and treatment response. This guide objectively compares the performance of these novel indices against traditional markers, framing the analysis within the context of their underlying biological mechanisms—the cellular components that form their foundation.

The Cellular Foundation of Systemic Inflammation

Systemic inflammation is a key player in cancer progression and other chronic diseases, influencing stages from tumor initiation to metastasis [6]. The tumor microenvironment, a complex ecosystem of cancer and host cells, is heavily influenced by systemic immune responses. Traditional inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), while useful, are not cancer-specific and can be influenced by many non-malignant conditions [6].

The cellular components of blood—neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets—are active participants in this inflammatory dialogue.

- Neutrophils promote tumor progression by fostering angiogenesis and suppressing anti-tumor immune responses.

- Lymphocytes, particularly cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, are crucial for executing anti-tumor cytotoxicity.

- Platelets shield circulating tumor cells from immune attacks and facilitate their invasion into new tissues.

- Monocytes differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages that support tumor growth and metastasis [6].

Novel inflammatory indices are mathematical formulas that integrate these cellular components into single, predictive ratios. By quantifying the balance between pro-tumor and anti-tumor forces within the host, they provide a dynamic snapshot of the systemic inflammatory state that is both cost-effective and readily accessible from standard blood tests [9] [6].

Comparative Performance: Novel Indices vs. Traditional Markers

Extensive research has evaluated the prognostic performance of novel systemic inflammatory indices, particularly in oncology. The following tables summarize key comparative data from recent clinical studies.

Table 1: Predictive Performance of Inflammatory Markers in Advanced Cancer Weight Loss (3 Weeks)

| Marker | Adjusted R² | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | 0.089 | One of the most optimal predictors |

| mGPS | 0.091 | One of the most optimal predictors |

| Albumin | 0.083 | Significant but less than CRP/mGPS |

| IL-6 | 0.078 | Significant but less than CRP/mGPS |

| NLR | 0.081 | Significant but less than CRP/mGPS |

| PLR | 0.080 | Significant but less than CRP/mGPS |

| Base Model | 0.064 | Without MoSI for comparison [10] |

Table 2: Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Early-Stage NSCLC (Overall Survival)

| Marker | Mean OS (Months) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| High NLR | 102.7 vs. 109.4 (Low) | 0.040 |

| Low LMR | 101.0 vs. 110.3 (High) | < 0.001 |

| High PLR | 104.1 vs. 110.1 (Low) | 0.017 |

| High PIV | Not Significant for OS | - [6] |

Table 3: Dynamic SII as a Predictor in High-Risk Pediatric Neuroblastoma

| Outcome Measure | Statistical Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Chemosensitivity | OR = 0.00, 95% CI: 0.00-0.03, P = 0.010 | Independent predictor |

| Event-Free Survival | HR = 1.35, P < 0.05 | Independent prognostic factor |

| Overall Survival | HR = 1.41, P < 0.05 | Independent prognostic factor |

| Predictive Accuracy | AUC: 0.766-0.932 | High accuracy [9] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data reveals a consistent pattern: novel inflammatory indices provide significant prognostic value across different cancer types.

- In advanced cancer cachexia, all markers of systemic inflammation (MoSI) significantly improved the base prediction model for weight loss at three weeks. However, the traditional marker CRP and the composite modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS), which incorporates CRP and albumin, demonstrated superior performance, yielding the highest adjusted R² values [10].

- In early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the novel indices NLR, PLR, and LMR were strong predictors of overall survival. Notably, the Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV), which integrates four cell types, was not significant for OS but was the only marker significantly associated with worse disease-free survival in this cohort [6].

- In high-risk pediatric neuroblastoma, the dynamic change in the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (ΔSII) during neoadjuvant chemotherapy was a powerful independent predictor of both treatment response and survival outcomes, with high predictive accuracy (AUC up to 0.932) [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The reliability of these findings hinges on standardized experimental protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical study investigating systemic inflammatory indices.

Patient Selection and Study Design

Most studies are retrospective, multicenter cohort analyses [6]. Key criteria include:

- Inclusion Criteria: Confirmed diagnosis (e.g., stage I-IIA NSCLC), patients undergoing specific treatment (e.g., R0 surgical resection), accessible preoperative blood samples within 15 days before treatment, and complete clinical follow-up data [6].

- Exclusion Criteria: Active infection, other active malignancies, hematologic/rheumatologic/autoimmune diseases that could affect CBC parameters, use of neoadjuvant therapy or immunosuppressive drugs like corticosteroids, and missing data [9] [6].

Blood Sample Processing and Data Calculation

- Blood Collection: Venous blood samples are collected in EDTA tubes prior to initiation of treatment.

- Hematological Analysis: Samples are analyzed using automated hematology analyzers (e.g., Sysmex XN-3000, Mindray BC-6800) to obtain absolute counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets [6].

- Index Calculation: Indices are calculated using standard formulas:

- NLR: Absolute neutrophil count / Absolute lymphocyte count

- PLR: Absolute platelet count / Absolute lymphocyte count

- LMR: Absolute lymphocyte count / Absolute monocyte count

- SII: (Absolute neutrophil count × Absolute platelet count) / Absolute lymphocyte count

- PIV: (Absolute neutrophil count × Absolute platelet count × Absolute monocyte count) / Absolute lymphocyte count [6]

Statistical Analysis

- Cut-off Values: Optimal cut-off values for classifying patients into "high" and "low" index groups are often determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

- Survival Analysis: Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) are typically assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests for comparison.

- Multivariate Analysis: Cox proportional hazards models are used to determine if an inflammatory index is an independent prognostic factor after adjusting for other clinical variables like age, sex, and tumor stage [9] [6].

Research Workflow for Inflammatory Indices

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Inflammatory Index Research

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Standard tubes for collecting venous blood samples; preserves cell integrity for a complete blood count (CBC). |

| Automated Hematology Analyzer | Instruments (e.g., Sysmex XN-3000, Mindray BC-6800) that provide precise absolute counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets. |

| Clinical Database | Curated electronic health records (EHR) providing essential patient demographics, treatment history, and follow-up survival data. |

| Statistical Software | Platforms (e.g., R, SPSS) for performing survival analysis, ROC curve analysis, and multivariate Cox regression to validate prognostic value. |

| Piperacillin Sodium | Piperacillin Sodium|Research Grade|RUO |

| Pantethine | Pantethine, CAS:16816-67-4, MF:C22H42N4O8S2, MW:554.7 g/mol |

Visualizing the Formula and Cellular Relationships

The formulas for systemic inflammatory indices are deceptively simple, but their components have complex biological relationships. The following diagram deconstructs the SII formula to illustrate these interactions.

SII Formula Deconstructed

The immune system maintains a delicate balance between protection and self-tolerance, with dysregulation manifesting in seemingly opposite yet mechanistically linked diseases. Autoimmunity and cancer represent two sides of the same coin: autoimmune diseases result from excessive immune activation against self-antigens, while cancer often persists due to insufficient immune recognition and destruction of malignant cells [11]. This paradoxical relationship centers on the breakdown of immune tolerance mechanisms, where specialized regulatory cell populations, effector molecules, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors collectively determine disease outcomes [11].

Traditional inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) have provided foundational insights into immune activation but offer limited specificity for differentiating disease types and monitoring complex immune dysregulation [12] [13]. The emerging class of systemic inflammatory indices, calculated from routine complete blood count parameters, offers a more nuanced reflection of the dynamic interactions between different immune cell populations in disease states [14] [13]. These cellular ratios, including the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), system inflammation response index (SIRI), and aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI), provide integrated measures of inflammation that correlate with disease activity, treatment response, and clinical outcomes across both autoimmune conditions and cancer [14] [13].

This review examines how these novel hematologic indices illuminate shared and distinct pathways of immune dysregulation in autoimmunity and cancer, with implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development. We compare the performance characteristics of traditional and novel inflammatory markers, detail experimental methodologies for their validation, and explore their emerging role in guiding targeted therapies, including immunotherapy.

Comparative Analysis of Inflammatory Markers

Traditional Inflammatory Markers

Traditional biomarkers have long served as cornerstones for assessing inflammatory burden in both autoimmune diseases and cancer. Acute-phase proteins such as CRP, serum amyloid A (SAA), fibrinogen, and procalcitonin are produced by the liver in response to inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6 [12]. These markers provide sensitive but non-specific measures of systemic inflammation, rising in response to diverse stimuli including infection, trauma, and autoimmune flares [12]. Cytokines themselves, including TNF-α, interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12), and IFN-γ, offer more specific insights into immune activation pathways but present technical challenges for routine clinical use due to their short half-lives, susceptibility to pre-analytical variables, and requirement for specialized assays [12].

In autoimmune conditions, these traditional markers correlate generally with disease activity but often lack the precision to guide targeted therapies. In cancer, they reflect the systemic inflammatory response to malignancy but provide limited information about the tumor-immune interface [12]. The discovery of immune checkpoint pathways and the development of cancer immunotherapies targeting PD-1 and CTLA-4 highlighted the need for more sophisticated biomarkers that reflect the complex interplay between tumors and the immune system [11] [15].

Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices

Novel systemic inflammatory indices derived from complete blood count parameters have emerged as integrated measures of immune status that reflect the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cellular components. These indices leverage the differential responses of various leukocyte populations and platelets to inflammatory stimuli, providing a composite picture of systemic inflammation that overcomes some limitations of traditional markers [14] [13].

Table 1: Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices: Calculations and Clinical Applications

| Index Name | Calculation Formula | Components Measured | Primary Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) | Platelets × Neutrophils/Lymphocytes | Platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte counts | RA, SLE, spondyloarthritis, various cancers [14] [13] |

| System Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) | Neutrophils × Monocytes/Lymphocytes | Neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte counts | Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer [14] |

| Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation (AISI) | Neutrophils × Platelets × Monocytes/Lymphocytes | Neutrophil, platelet, monocyte, lymphocyte counts | Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer [14] |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) | Neutrophils/Lymphocytes | Neutrophil, lymphocyte counts | Broad inflammatory conditions, cancer prognosis [14] |

| Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) | Platelets/Lymphocytes | Platelet, lymphocyte counts | Autoimmune diseases, cancer progression [14] |

The SII has demonstrated particular utility across autoimmune conditions. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), elevated SII correlates with disease activity scores, response to TNF-α inhibitors, and reduced serum Klotho levels [13]. In spondyloarthritis (SpA), including ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), the SII associates with disease activity scores, musculoskeletal imaging findings, and treatment response [13]. For systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the SII tracks global disease activity and predicts specific manifestations such as lupus nephritis and pregnancy outcomes, reflecting underlying features like lymphopenia, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and platelet activation [13].

In cancer, these indices provide prognostic information beyond conventional markers. The SII, SIRI, and AISI have shown significant positive correlations with hypertension prevalence in large epidemiological studies, with hypertension risk increasing progressively across quartiles of these indices [14]. In continuous analyses, each unit increase in logSII, logSIRI, and logAISI was associated with a 20.3%, 20.1%, and 23.7% increased risk of hypertension, respectively [14]. Similar relationships exist with cancer progression and response to immunotherapy, reflecting the role of systemic inflammation in tumor development and immune evasion [16] [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Novel Inflammatory Markers

| Marker Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Disease Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Markers | CRP, ESR, cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) | Well-established, standardized assays, low cost | Limited specificity, non-specific to immune context | Low to moderate [12] |

| Novel Indices | SII, SIRI, AISI, NLR, PLR | Integrated immune picture, routine data, cost-effective | Influenced by non-immune factors (e.g., infection) | Moderate to high [14] [13] |

| Molecular Biomarkers | PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden | High specificity for therapy response | Require specialized testing, tissue sampling | High for specific therapies [16] |

| Microbiome Signatures | Gut microbiota profiles | Predictive for immunotherapy response | Emerging validation, complex analysis | Potentially high [11] [16] |

Shared Mechanisms of Immune Dysregulation

Breakdown of Immune Tolerance

The fundamental connection between autoimmunity and cancer lies in the disruption of immune tolerance mechanisms that normally maintain equilibrium between protection and self-recognition [11]. Central tolerance occurs in primary lymphoid organs through deletion of self-reactive lymphocytes, while peripheral tolerance mechanisms regulate potentially autoreactive cells that escape central selection [11]. Specialized cell populations including regulatory T cells (Tregs), regulatory B cells (Bregs), tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDCs), and M2 macrophages maintain this balance under normal conditions [11].

In autoimmunity, genetic predispositions combined with environmental triggers disrupt these regulatory mechanisms, leading to loss of self-tolerance. Key defects include impaired negative selection of self-reactive T cells in the thymus, often associated with mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene, which normally promotes expression of tissue-restricted antigens in thymic epithelial cells [11]. Similarly, defects in B-cell central tolerance involving mutations in PTPN22, Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), and Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways contribute to accumulation of autoreactive B cells in the periphery [11].

In cancer, malignant cells exploit these same tolerance mechanisms to evade immune destruction. Tumors create immunosuppressive microenvironments by recruiting regulatory cell populations such as Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which inhibit anti-tumor immune responses [11] [15]. They also upregulate immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1 and CTLA-4 that normally function to prevent excessive immune activation, effectively hijacking self-tolerance pathways to achieve immune escape [11] [15].

Metabolic Reprogramming and Immune Suppression

Metabolic alterations in the tissue microenvironment represent another shared mechanism between autoimmunity and cancer. Tumor cells frequently undergo metabolic reprogramming toward aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), resulting in lactate accumulation and acidification of the tumor microenvironment [15]. This acidic environment directly inhibits the function of immune cells including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells [15]. Lactic acid impairs T-cell activation and proliferation by disrupting key signaling pathways, reduces production of cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, and induces macrophages to adopt an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype [15].

Similar metabolic disturbances occur in autoimmune conditions, where altered nutrient availability and metabolic checkpoints influence immune cell differentiation and function. For example, rapidly proliferating T cells in inflammatory sites undergo glutaminolysis, producing ammonia that can induce a unique form of T-cell death through lysosomal alkalization and mitochondrial damage [15]. These shared metabolic pathways offer potential therapeutic targets for both disease classes.

Diagram 1: Shared immune dysregulation pathways in autoimmunity and cancer. Both disease classes involve disruption of normal immune tolerance mechanisms through genetic, cellular, metabolic, and microbiome factors, leading to opposite clinical manifestations.

Microbiome Influences on Immune Function

The gut microbiome represents a crucial interface between environmental factors and immune function in both autoimmunity and cancer [11]. Gut dysbiosis, characterized by altered microbial diversity and composition, associates with multiple autoimmune diseases including Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and type 1 diabetes [11]. In Crohn's disease, specific polymorphisms in the NOD2/CARD15 gene impair recognition of bacterial cell wall components, contributing to dysregulated immune responses [11]. Molecular mimicry between microbial and self-antigens represents another mechanism linking infection to autoimmune activation, as observed with Coxsackievirus and Rotaviruses in type 1 diabetes [11].

In cancer, the gut microbiome modulates responses to immunotherapy. The abundance of specific bacteria such as Bifidobacterium species and Akkermansia muciniphila associates with improved tumor control and enhanced responses to anti-PD-1 therapy [11]. Microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) exhibit anti-carcinogenic effects, while other metabolites like N-nitroso compounds (NOCs) demonstrate procarcinogenic properties [11]. These findings highlight the microbiome as a promising therapeutic target for modulating immune responses in both autoimmunity and cancer.

Experimental Approaches and Diagnostic Validation

Biomarker Discovery Methodologies

The identification and validation of novel inflammatory biomarkers involves sophisticated computational and experimental approaches. Transcriptomic analysis from public databases like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) enables identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between disease and control samples [17]. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) identifies gene modules correlated with clinical phenotypes, while machine learning algorithms including random forest (RF), least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) pinpoint hub genes with diagnostic potential [17].

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) quantifies immune cell infiltration in tissue samples based on specific gene signatures, revealing differences in immune landscapes between disease states [17]. For example, in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), these approaches identified three diagnostic biomarkers—PLAC8, S100A8, and PPBP—with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.887, 0.818, and 0.871, respectively, for distinguishing patients from controls [17]. Immunohistochemical validation confirmed elevated PLAC8 expression and distinct immune cell patterns in IC/BPS tissues, supporting its role as a promising diagnostic biomarker [17].

Diagram 2: Biomarker discovery and validation workflow. This process integrates computational analyses with experimental validation to identify and verify diagnostic biomarkers for immune-related diseases.

Detection Technologies

Advanced detection technologies enable precise measurement of inflammatory biomarkers in clinical and research settings. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) provide spatial information about biomarker expression within tissues, allowing correlation with histopathological features [17] [16]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) facilitate quantitative measurement of soluble biomarkers in blood and other body fluids, though challenges include reduced protein activity, non-specific interactions, and potential cross-reactivity [16]. Innovations such as streptavidin-biotin complexes and smaller molecule labeling enhance ELISA sensitivity and specificity [16].

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) offers ultra-sensitive detection of biomarkers in complex biological samples by leveraging electromagnetic and chemical enhancements at metal surfaces [16]. Gold and silver nanoparticles serve as enhancing agents, with polyethylene glycol (PEG) layers improving stability in biological environments [16]. Biosensors represent another emerging technology, providing high sensitivity, rapid detection, and non-invasive biomarker analysis through biorecognition elements and signal transducers that convert biological events into measurable electrical signals [16]. These technologies advance biomarker discovery along the continuum from initial detection to clinical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry Reagents | PLAC8, CXCL10, c-Kit (CD117), SDC1 (CD138), CD163 antibodies [17] | Tissue-based protein localization | Spatial visualization of biomarker expression in disease tissues |

| Cell Isolation Kits | T cell, B cell, neutrophil, monocyte isolation kits [14] | Immune cell purification | Obtain specific cell populations for functional studies |

| Cytokine Detection Assays | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ ELISA kits [12] [18] | Inflammatory mediator quantification | Measure cytokine levels in serum, plasma, and tissue supernatants |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD56, FoxP3, CD25 [18] | Immune cell phenotyping | Characterize immune cell populations and activation states |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | RNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR primers [17] | Gene expression analysis | Quantify transcript levels of inflammatory genes |

| Protein Analysis Tools | Western blot reagents, co-immunoprecipitation kits [17] | Protein expression and interaction studies | Detect protein levels and protein-protein interactions |

| Piperidolate Hydrochloride | Piperidolate Hydrochloride, CAS:129-77-1, MF:C21H26ClNO2, MW:359.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Piperonyl Butoxide | Piperonyl Butoxide (PBO) | Piperonyl butoxide is a potent pesticide synergist for research. It inhibits insect metabolic enzymes to enhance insecticide efficacy. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Predictive Biomarkers for Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment, but response variability and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) remain significant challenges [18] [16]. Biomarkers that predict both therapeutic efficacy and toxicity are urgently needed to guide personalized treatment approaches [18] [16]. Current biomarkers including programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor mutational burden (TMB) guide immunotherapy selection but have limited predictive accuracy [16].

Recent research identifies pre-inflammatory immune states associated with irAE risk. A multi-omic biomarker analysis revealed that patients with elevated levels of antibody-producing cells and autoantibodies, heightened interferon-gamma activity, and increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signals before treatment were more likely to develop toxicities once immunotherapy began [18]. These findings suggest that a clinically silent proinflammatory state predisposes patients to irAEs, offering potential opportunities for preventive strategies [18].

The gut microbiome also shows promise as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response. Specific microbial signatures, including enrichment of Bifidobacterium species and Akkermansia muciniphila, associate with improved tumor control and response to anti-PD-1 therapy [11] [16]. These microbiome features may modulate immune responses through metabolite production and immune cell education, potentially offering targets for therapeutic manipulation to enhance treatment outcomes [11] [16].

Integrative Biomarker Frameworks

The complexity of immune dysregulation in autoimmunity and cancer necessitates integrative approaches that combine multiple biomarker classes. A Comprehensive Oncological Biomarker Framework incorporates genetic and molecular testing, imaging, histopathology, multi-omics, and liquid biopsy to generate a molecular fingerprint for each patient [16]. This holistic approach supports individualized diagnosis, prognosis, treatment selection, and response monitoring, addressing tumor heterogeneity and immune evasion mechanisms [16].

Such frameworks unite molecular insights with clinical and social factors, potentially improving patient outcomes through precision oncology. The integration of novel inflammatory indices with traditional biomarkers, molecular profiles, and microbiome data provides a more comprehensive assessment of immune status than any single marker class alone [14] [13] [16]. This is particularly relevant for diseases like interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), where heterogeneous clinical presentations benefit from multi-parameter assessment incorporating inflammatory markers, immune cell infiltration patterns, and specific protein biomarkers [17].

Therapeutic Monitoring and Disease Stratification

Novel inflammatory indices show significant utility for monitoring treatment response and stratifying disease subtypes across both autoimmunity and cancer. In rheumatoid arthritis, SII levels correlate with disease activity and response to TNF-α inhibitors, providing a readily measurable parameter for assessing therapeutic efficacy [13]. Similarly, in spondyloarthritis, SII associates with treatment response and musculoskeletal imaging findings, offering a composite measure of inflammatory burden [13].

In cancer, these indices help identify patients with heightened systemic inflammation who may benefit from more aggressive management or specific therapeutic approaches. The association between SII, SIRI, and AISI with hypertension prevalence underscores the relationship between systemic inflammation and cardiovascular comorbidity in cancer patients [14]. Restricted cubic splines analysis revealed non-linear relationships between these inflammatory markers and hypertension prevalence, with a per standard deviation increase in any of these variables associated with a respective 9%, 16%, and 11% increase in hypertension prevalence [14]. These findings highlight the potential of inflammatory indices for risk stratification and comorbidity management in cancer patients.

The comparison between traditional inflammatory markers and novel systemic inflammatory indices reveals a paradigm shift in how we quantify and interpret immune dysregulation in autoimmunity and cancer. While traditional markers like CRP and cytokines provide important information about inflammatory burden, they offer limited insights into the complex cellular interactions underlying disease pathogenesis. Novel indices derived from routine complete blood count parameters—SII, SIRI, AISI, NLR, and PLR—provide integrated measures that reflect the balance between pro-inflammatory and regulatory immune components, correlating with disease activity, treatment response, and clinical outcomes across both autoimmune conditions and cancer.

The shared mechanisms of immune dysregulation in autoimmunity and cancer, including breakdown of tolerance mechanisms, metabolic reprogramming, and microbiome influences, highlight why these cellular ratios provide meaningful clinical information. Their calculation from routine laboratory parameters makes them economically attractive for both resource-rich and limited settings, though interpretation requires consideration of potential confounders including concurrent infections and non-immune conditions.

As we advance toward increasingly personalized approaches to immune-mediated diseases, these novel inflammatory indices will likely play growing roles in diagnosis, prognosis, therapeutic selection, and response monitoring. Their integration with molecular biomarkers, microbiome profiling, and clinical features within comprehensive biomarker frameworks holds particular promise for optimizing outcomes in both autoimmunity and cancer. Future research should focus on standardizing cut-off values, validating indices across diverse populations, and elucidating the specific cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying their association with disease activity and progression.

For decades, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) have served as cornerstone biomarkers in clinical practice for detecting and monitoring inflammation. These traditional acute-phase reactants provide valuable but limited information about systemic inflammatory activity. As research advances, particularly in complex diseases like cancer, autoimmune conditions, and chronic inflammatory disorders, significant limitations of these conventional markers have emerged. This review examines the technical and clinical constraints of CRP and ESR while exploring the promise of novel systemic inflammatory indices that offer enhanced prognostic capabilities and biological insight.

Fundamental Limitations of Traditional Inflammatory Markers

Technical and Biological Constraints

CRP and ESR, while widely accessible and inexpensive, suffer from several inherent limitations that restrict their diagnostic and prognostic utility:

Limited specificity: Both markers elevate in response to any inflammatory stimulus, including infections, trauma, autoimmune flares, and tissue damage, making it difficult to distinguish between these conditions [12]. ESR is particularly prone to false elevations from non-inflammatory conditions including anemia, renal disease, female sex, older age, and obesity [19].

Variable kinetics: CRP responds rapidly to inflammatory stimuli, with doubling times of approximately 6-8 hours and peak levels within 24-48 hours. In contrast, ESR rises more slowly over days and normalizes gradually over weeks, even after clinical improvement [19] [20]. This discordance in timing can lead to conflicting clinical pictures.

Insensitivity to low-grade inflammation: Both markers frequently remain within normal limits despite histologically confirmed inflammation. A 2018 study of rheumatoid arthritis patients found that 49.4% of patients with normal CRP levels nonetheless had histological evidence of synovial inflammation [21].

Disease-specific limitations: In certain conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus, patients with significant disease activity may display normal CRP levels, possibly due to interferon-mediated inhibition of CRP production [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Limitations of Traditional Inflammatory Markers

| Parameter | CRP | ESR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Basis | Acute-phase protein produced by hepatocytes | Measure of red blood cell aggregation influenced by fibrinogen and immunoglobulins |

| Response Time | Hours (rapid) | Days (slow) |

| Half-Life | 6-8 hours | Days to weeks |

| Major Influencing Factors | Inflammation, infection, tissue damage, obesity | Inflammation, anemia, renal disease, age, sex, red cell abnormalities |

| Key Limitations | Non-specific, misses low-grade inflammation | Affected by numerous non-inflammatory factors, slow to normalize |

Diagnostic Performance Concerns in Clinical Practice

The diagnostic accuracy of CRP and ESR has been increasingly questioned across various medical conditions:

Orthopaedic infections: Recent meta-analyses report sensitivity and specificity ranging from 52% to 83% for both markers, with positive and negative likelihood ratios providing limited diagnostic value [22].

Rheumatoid arthritis monitoring: Research indicates poor correlation between these serum markers and actual synovial inflammation. One study found only a weak positive correlation between DAS28-CRP and synovial inflammation (rho = 0.23, p = 0.0011) [21].

Spinal infections: While useful for ruling out disease at very low levels (ESR ≤ 20 mm/h or CRP ≤ 1.2 mg/dL provided 90% sensitivity), their elevation alone lacks specificity for definitive diagnosis [23].

The cumulative evidence has led some experts to characterize routine ESR and CRP testing as "zombie tests" that persist despite recognized limitations, driven more by tradition than demonstrated clinical utility in many scenarios [22].

Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices: Principles and Advantages

Novel inflammatory indices, derived from routine complete blood count parameters and other readily available laboratory values, offer several theoretical and practical advantages over traditional markers:

Comprehensive immune status assessment: These indices integrate multiple leukocyte populations, providing a more holistic view of the immune-inflammatory response compared to single parameters [6].

Dynamic monitoring capability: With short turnaround times and minimal costs, these ratios can be serially monitored to track disease progression and treatment response [9].

Tumor microenvironment reflection: In oncology, these indices potentially capture the balance between pro-inflammatory, pro-tumorigenic responses and anti-tumor immunity [6].

Prognostic stratification: Multiple studies demonstrate superior prognostic value for clinical outcomes compared to traditional markers across various diseases [6] [24].

Table 2: Novel Systemic Inflammatory Indices and Their Clinical Applications

| Index | Calculation | Primary Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) | Absolute neutrophils / Absolute lymphocytes | Prognostic in cancer, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory conditions |

| Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) | Absolute platelets / Absolute lymphocytes | Predictive of treatment response and outcomes in solid tumors |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR) | Absolute lymphocytes / Absolute monocytes | Prognostic marker in lymphomas and solid tumors |

| Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) | (Platelets × Neutrophils) / Lymphocytes | Predictive of outcomes in multiple cancer types |

| Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV) | (Neutrophils × Platelets × Monocytes) / Lymphocytes | Comprehensive assessment of systemic immune inflammation |

| C-reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio (CAR) | CRP / Albumin | Predicts treatment resistance and outcomes in inflammatory conditions |

Comparative Performance: Traditional vs. Novel Markers

Evidence from Malignancies

In oncology, novel inflammatory indices have demonstrated consistent prognostic value superior to traditional markers:

Early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: A 2025 multicenter study of 2,159 patients found that elevated preoperative NLR (102.7 vs. 109.4 months, p = 0.040), low LMR (101 vs. 110.3 months, p < 0.001), and high PLR (104.1 vs. 110.1 months, p = 0.017) all predicted worse overall survival [6].

High-risk neuroblastoma: Research published in 2025 demonstrated that dynamic changes in SII during neoadjuvant chemotherapy strongly correlated with treatment response (Spearman r = 0.606, P < 0.001) and served as an independent prognostic factor for both event-free and overall survival (HR = 1.35 and 1.41, respectively, P < 0.05) [9].

Evidence from Renal and Autoimmune Diseases

Novel indices also show promise in non-malignant conditions:

Minimal change disease: A 2025 study identified CAR ≥ 0.196 and dNLR ≥ 1.32 as independent predictors of steroid resistance and relapse in adult-onset minimal change disease, enabling early identification of high-risk patients [24].

Rheumatoid arthritis: Research indicates that composite disease activity scores incorporating clinical findings provide more accurate assessment than CRP or ESR alone, with one study concluding that "it is not necessary to obtain both ESR and CRP measures for clinical disease activity assessment" [25].

Experimental Approaches for Inflammatory Marker Evaluation

Synovial Biopsy Methodology for Rheumatoid Arthritis Validation

A 2018 study employed needle arthroscopy to directly validate serum markers against histological evidence of synovial inflammation [21]:

- Patient population: 223 consecutive RA patients with knee arthralgia

- Sample collection: Peripheral blood samples for CRP, ESR, and DAS28-CRP immediately before arthroscopy

- Tissue processing: Synovial biopsies embedded in OCT medium, sectioned at 7μm, stained with H&E

- Histological scoring: Inflammation graded over 3 ordinal categories (0 = no inflammation, 1 = mild inflammation, 2 = moderate to severe inflammation)

- Statistical analysis: Spearman correlation between serum markers and histological scores

This direct tissue validation approach revealed the significant discrepancy between serum markers and actual synovial inflammation that would be undetectable using serum markers alone.

Hematological Parameter Analysis for Novel Indices

Studies evaluating novel inflammatory indices typically follow standardized methodologies [6]:

- Blood sample collection: Venous blood collected in EDTA tubes within specified timeframes before intervention

- Automated complete blood count: Analysis using standardized hematology analyzers (e.g., Sysmex XN-3000, Mindray BC-6800)

- Index calculation: Derived from absolute cell counts using standardized formulas

- Statistical analysis: Optimal cut-off values determined using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis

- Outcome assessment: Correlation with clinical outcomes (overall survival, disease-free survival, treatment response)

This methodology allows for reproducible calculation of novel indices across different laboratory settings.

Signaling Pathways and Biological Rationale

The biological plausibility of novel inflammatory indices stems from their reflection of fundamental immune processes:

This diagram illustrates how novel inflammatory indices integrate multiple aspects of the immune response to provide a more comprehensive assessment of inflammatory status than traditional markers. The systemic immune response to various stimuli involves coordinated changes in different leukocyte populations, which these indices capture mathematically.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Materials for Inflammatory Marker Studies

| Reagent/Instrument | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Preservation of cellular morphology and prevention of coagulation | Standardized blood sample collection for complete blood count parameters |

| Automated Hematology Analyzers | Quantitative assessment of blood cell populations | Precise measurement of absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, and monocyte counts |

| CRP Immunoassays | Quantitative measurement of C-reactive protein | Standardized CRP measurement for traditional assessment and CAR calculation |

| OCT Embedding Medium | Tissue preservation for cryosectioning | Processing of synovial biopsies for histological validation |

| Immunohistochemistry Kits | Cell-specific identification in tissue sections | Characterization of inflammatory cell infiltrates (CD3, CD19, CD68) |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits | Quantification of specific inflammatory cytokines | Measurement of IL-6, TNF-α, and other cytokines driving acute phase responses |

The limitations of traditional inflammatory markers CRP and ESR are increasingly evident as research advances toward more sophisticated assessments of systemic inflammation. While these conventional tests retain utility in specific clinical scenarios, novel inflammatory indices derived from routine complete blood count parameters offer enhanced prognostic capability, better reflection of tumor microenvironment interactions, and more comprehensive immune status assessment. The integration of these novel indices into both clinical research and practice represents a paradigm shift in how inflammation is quantified and interpreted across various disease states. Future directions should focus on standardizing cutoff values, validating indices in diverse populations, and exploring their utility in guiding targeted therapies.

From Bench to Bedside: Calculating, Applying, and Integrating Novel Indices in Research and Clinics

Standardized Calculation Methods for Key Indices (SII, NLR, PLR, PIV)

In the evolving landscape of clinical and translational research, novel systemic inflammatory indices have emerged as powerful, cost-effective tools for prognostic assessment and disease monitoring. These hematological biomarkers, derived from routine complete blood count (CBC) data, provide integrated measures of inflammatory status, immune response, and physiological stress. Unlike traditional inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) which require specialized assays, indices such as the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), and Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV) leverage routinely available laboratory parameters, offering multidimensional insights into patient health status without additional financial burden [26] [27].

The clinical significance of these indices extends across diverse medical specialties, from oncology and cardiology to endocrinology and immunology. Research demonstrates their utility in predicting disease progression, treatment response, and survival outcomes across various pathological conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and chronic inflammatory states [26] [27] [28]. Their calculation represents a paradigm shift in inflammatory biomarker research, enabling comprehensive assessment of the complex interplay between inflammation, immunity, and disease pathophysiology through standardized, reproducible formulas accessible to researchers and clinicians worldwide.

Comparative Analysis of Key Inflammatory Indices

The table below provides a detailed comparison of the standardized calculation methods, components, and research applications for four key inflammatory indices.

| Index | Full Name | Standardized Calculation Formula | Components Measured | Research & Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SII | Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index | Platelets, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes [26] | Predicts obesity risk and metabolic disease; prognostic marker in cancer, T2DM with insulin resistance, and cardiovascular diseases [26] [27]. | |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio | Neutrophils, Lymphocytes [29] [30] | Marker of systemic inflammation and physiologic stress; predictive for mortality in sepsis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke; elevated in overtraining syndrome [29] [30]. | |

| PLR | Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio | Platelets, Lymphocytes [31] [28] | Assesses inflammation-clotting balance; prognostic factor in cardiovascular disease, cancer, and postoperative atrial fibrillation; reflects inflammatory load and thrombotic risk [31] [28]. | |

| PIV | Pan-Immune Inflammation Value | Platelets, Neutrophils, Monocytes, Lymphocytes | Note: Standardized formula confirmation from search results was limited; consult primary literature for detailed PIV methodology. |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

The formulas demonstrate a progressive complexity in integrating immune components. While NLR offers a fundamental ratio of innate to adaptive immunity, PLR introduces the platelet component reflecting thrombotic and inflammatory pathways. SII provides a more comprehensive integration by combining platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts into a single index, potentially offering superior prognostic value in conditions like cancer and metabolic disorders [26] [27]. The search results did not provide sufficient authoritative information to confirm the standardized calculation for PIV; researchers should consult specialized immunological literature for this parameter.

These indices are particularly valuable in chronic disease research. Recent studies have established significant correlations between elevated SII, NLR, and PLR values and conditions such as insulin resistance in T2DM, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases [26] [27]. For instance, in T2DM research, these indices show positive correlations with HOMA-IR scores and serve as independent risk factors for insulin resistance, providing accessible assessment tools without requiring additional specialized testing [26].

Experimental Protocols for Index Validation

Laboratory Methodology for Blood Parameter Analysis

Accurate calculation of inflammatory indices depends on standardized blood collection and analysis protocols. Researchers should implement the following methodology based on current literature:

Blood Collection: Venous blood samples should be collected after recommended fasting periods (typically 8-12 hours) to minimize diurnal variation and dietary influences. Samples for complete blood count (CBC) should be collected in EDTA-anticoagulated containers following standardized phlebotomy procedures [31] [27] [28].

Sample Processing: Analysis should be performed using automated hematology analyzers (e.g., SYSMEX-XN9000 series or similar systems) following manufacturer protocols and standardized laboratory procedures [26] [28]. Samples should be processed promptly after collection to prevent EDTA-induced pseudothrombocytopenia or other artifacts that may affect platelet counts [28].

Quality Control: Laboratories should implement daily quality control procedures using calibrated materials and participate in proficiency testing programs to ensure analytical precision and accuracy across all measured parameters [26].

Standardized Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Following data collection, researchers should adhere to these analytical protocols:

Index Calculation: Calculate each index using the standardized formulas presented in Section 2. All cellular components should be expressed in consistent units, typically ×10â¹/L [26] [29].

Data Transformation: For indices with right-skewed distributions (particularly SII), apply logarithmic transformation (lnSII) before statistical analysis to normalize distributions and improve model stability in regression analyses [27].

Statistical Analysis: Employ appropriate statistical methods based on research objectives:

- Use Spearman's rank correlation analysis to evaluate relationships between inflammatory indices and continuous clinical variables (e.g., HOMA-IR scores) [26]

- Implement multivariable logistic regression models to assess independent predictive value while adjusting for potential confounders (age, gender, comorbidities, socioeconomic factors) [27]

- Utilize Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine discriminatory power and optimal cut-off values for disease prediction [26] [27]

Methodological Considerations and Confounding Factors

Researchers must account for several pre-analytical and biological variables that can influence inflammatory index values:

Temporal Variations: Lymphocyte counts demonstrate diurnal or circadian fluctuations, with T-cell numbers varying up to 20% between morning and night [28]. Standardize sampling times across study participants to minimize this variation.

Physiological Influences: Pregnancy, acute exercise (particularly high-intensity interval training), smoking status, and age can significantly affect cellular counts and derived indices [30] [28]. Document and adjust for these factors in analysis.

Medication Effects: Corticosteroids, cytotoxic therapies, and other medications can alter differential white cell counts [31] [28]. Record medication use and consider exclusion criteria or statistical adjustment.

Ethnic and Demographic Variations: NLR values demonstrate ethnic variations, with lower values typically observed in people of African-Caribbean or black African origin compared to white populations [30]. Account for demographic factors in study design and interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key reagents, instruments, and materials required for implementing standardized inflammatory index protocols in research settings.

| Category | Item | Specification/Model | Research Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection | EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | 3mL-5mL K2EDTA or K3EDTA | Anticoagulated sample preservation for CBC analysis [28] |

| Laboratory Analyzers | Automated Hematology Analyzer | SYSMEX-XN9000 series [26] | Precise quantification of blood cellular components |

| Laboratory Analyzers | Automated Biochemical Analyzer | Hitachi-008as [26] | Measurement of additional parameters (glucose, lipids) for comprehensive assessment |

| Analysis Software | Statistical Analysis Package | SPSS, R, or equivalent | Performance of multivariable regression, ROC analysis, and other statistical evaluations [26] [27] |

| Quality Control | Laboratory Quality Control Materials | Manufacturer-specific controls | Daily quality assurance for analytical precision and accuracy [26] |

Integration with Traditional Inflammatory Markers

While novel inflammatory indices provide valuable insights, they should be interpreted within a broader diagnostic context alongside traditional inflammatory markers:

Complementary Role: SII, NLR, and PLR complement rather than replace traditional markers like CRP and IL-6. Research demonstrates that these indices often provide independent prognostic information beyond conventional markers [27].

Comprehensive Assessment: For a complete inflammatory profile, researchers should consider combining novel indices with established markers. For example, in T2DM research, SII and NLR showed significant correlations with HOMA-IR scores while providing additional information beyond traditional metabolic parameters [26].

Methodological Advantages: The cost-effectiveness and routine availability of CBC parameters make these indices particularly valuable in resource-limited settings or for large-scale epidemiological studies where specialized inflammatory marker testing may be impractical or cost-prohibitive [26] [27].

The standardized calculation methods for SII, NLR, PLR, and other inflammatory indices represent a significant advancement in biomarker research, offering reproducible, accessible tools for assessing systemic inflammation across diverse research applications. As the field evolves, further validation of standardized protocols and population-specific reference ranges will enhance the utility of these indices in both research and clinical practice.

This comparison guide provides a systematic evaluation of novel systemic inflammatory indices against traditional biomarkers for assessing disease activity and severity. With the limitations of single-marker approaches and complex scoring systems increasingly apparent in clinical practice, composite indices derived from routine blood parameters offer a promising alternative for risk stratification. This review synthesizes recent evidence (2024-2025) from multiple clinical domains—including pancreatic diseases, oncology, psychiatry, and nephrology—to objectively compare the prognostic performance, operational characteristics, and clinical utility of emerging inflammatory biomarkers. Data extraction focused on predictive accuracy, statistical robustness, and practical implementation across diverse patient populations to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals about the most promising biomarkers for integration into clinical trials and practice.

The accurate assessment of disease activity and severity remains a fundamental challenge in clinical medicine and therapeutic development. Traditional inflammatory markers—including C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and interleukin-6 (IL-6)—have established roles in monitoring inflammatory conditions but possess recognized limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic capability [32] [13]. Similarly, multi-parameter clinical scoring systems (e.g., APACHE-II, BISAP, Ranson criteria), while valuable, often incorporate numerous complex variables that limit their practicality in routine clinical settings and rapid triage situations [5].

In recent years, novel systemic inflammatory indices derived from routine complete blood count (CBC) parameters have emerged as cost-effective, readily accessible alternatives that provide multidimensional insights into host inflammatory and immune status [33] [13]. These composite biomarkers, including the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR), and pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV), integrate multiple cellular pathways to offer a more comprehensive reflection of the balance between pro-inflammatory forces, immune responsiveness, and metabolic health [5] [33]. Their calculation leverages widely available laboratory data, presenting minimal additional healthcare costs while potentially offering superior prognostic performance across diverse disease states.

This review operates within the broader thesis that these novel indices represent a paradigm shift in inflammatory profiling, potentially surpassing traditional markers in prognostic accuracy, clinical utility, and practical implementation. We present a direct, evidence-based comparison of their performance against established biomarkers and scoring systems, supported by experimental data from recent clinical investigations across multiple medical specialties.

Quantitative Comparison of Inflammatory Biomarkers

Table 1: Prognostic Performance of Novel Inflammatory Indices Across Disease States

| Biomarker | Formula | Clinical Context | Predictive Power (AUC/HR/C-index) | Statistical Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHR | Neutrophils/HDL Cholesterol | HTG-AP Severity (MSAP+SAP) | AUC: 0.701; OR (Q3 vs Q1): 6.03 | P < 0.001 | [5] |

| SII | (Neutrophils × Platelets)/Lymphocytes | iCCA Prognosis | C-index (OS): 0.682; HR (OS): 2.488 | P < 0.001 | [33] |

| PIV | (Neutrophils × Monocytes × Platelets)/Lymphocytes | iCCA Prognosis | C-index (OS): 0.682; Time-AUC (OS): 0.695 | P < 0.001 | [33] |

| SIRI | (Neutrophils × Monocytes)/Lymphocytes | HTG-AP Severity | OR (Q3 vs Q1): 3.12 | P < 0.001 | [5] |

| NPAR | Neutrophil Percentage/Albumin | Sarcopenia Screening | AUC: 0.784; OR (Q4 vs Q1): 1.70 | P < 0.05 | [34] |

| NLR | Neutrophils/Lymphocytes | Depression Discrimination | AUC: >0.70 | P < 0.05 | [35] |

| CAR | CRP/Albumin | Steroid Resistance in MCD | Cutoff: ≥0.196 | P < 0.05 | [24] |

| dNLR | Neutrophils/(WBC - Neutrophils) | Relapse in MCD | Cutoff: ≥1.32 | P < 0.05 | [24] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Novel vs. Traditional Inflammatory Markers

| Comparison | Clinical Context | Key Findings | Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHR vs. Traditional Scoring Systems | HTG-AP Severity Prediction | NHR (AUC: 0.701) outperformed traditional systems with higher PPV; BISAP/APACHE-II have PPV 40-50% | Better positive prediction of severe disease | [5] |

| PIV vs. 11 Other Inflammatory Indices | iCCA Prognosis | PIV demonstrated superior prognostic performance (C-index: 0.682) vs. NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, SIRI | Best multidimensional biomarker in oncology | [33] |

| SII/SIRI vs. Classical Hematological Parameters | Depression and Suicide Risk | SII and SIRI significantly higher in MDD vs. controls; NLR performed better for distinguishing suicide attempts | Novel indices good for diagnosis, classical for specific outcomes | [35] |

| Novel Indices (SII) vs. CRP/ESR | Autoimmune Diseases (RA, SLE, SpA) | SII provides broader immune insights than CRP/ESR alone; correlates with disease activity and treatment response | More comprehensive inflammation assessment | [13] |

| NPAR vs. SII | Sarcopenia Screening | NPAR (AUC: 0.784) outperformed SII (AUC: N/A) for sarcopenia prediction | Incorporation of nutritional parameter adds value | [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Retrospective Cohort Design for Inflammatory Index Validation

The predominant methodological approach for evaluating novel inflammatory indices involves retrospective cohort studies analyzing existing clinical and laboratory data. The protocol typically includes:

Patient Population Definition: Studies establish clear inclusion/exclusion criteria to create homogeneous cohorts. For example, the HTG-AP study enrolled 340 patients with clearly defined diagnostic criteria (serum triglycerides ≥11.30 mmol/L or 500-1000 mg/dL with chylomicronemia) and severity stratification according to Revised Atlanta Classification (mild, moderate-severe, severe) [5]. Similarly, the iCCA study included 312 patients from three medical centers who underwent curative resection between 2014-2022, excluding those with preoperative therapies or other malignancies [33].

Data Collection Protocol: Researchers extract demographic, clinical, and laboratory data from electronic health records. Key variables typically include:

- Complete blood count parameters (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets)

- Metabolic panels (HDL cholesterol, albumin, triglycerides)

- Inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR when available)

- Disease-specific severity scores and clinical outcomes

Biomarker Calculation: Novel indices are calculated from baseline laboratory data using standardized formulas before treatment initiation or at disease diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis Plan: Studies employ multivariable analyses to adjust for potential confounders. The HTG-AP study used restricted cubic splines to reveal nonlinear associations and multivariable logistic regression with fully adjusted models [5]. The iCCA study utilized Harrell's concordance index (C-index), time-dependent AUC, and Brier scores to evaluate prognostic performance [33].

Longitudinal Monitoring Protocol

For dynamic assessment of inflammatory responses, longitudinal studies employ serial measurements:

Time-Point Selection: The COVID-19 inflammatory marker study collected blood samples at 24h, 48h, 7 days, and >1 month post-discharge to track temporal patterns [32].

Phenotype Clustering: Researchers often use cluster analysis to identify distinct inflammatory phenotypes. The COVID-19 study identified four patient clusters with unique inflammatory patterns that remained stable over time [32].

Outcome Correlation: Statistical models correlate biomarker levels with clinical outcomes such as ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, mortality (COVID-19); overall survival and disease-free survival (oncology); and treatment response or relapse (nephrology) [32] [33] [24].

Biomarker Integration in Disease Pathophysiology

The following diagram illustrates how novel inflammatory indices integrate multiple physiological pathways to provide a comprehensive assessment of disease activity and severity:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Inflammation Assessment Through Novel Indices

This diagram illustrates how novel inflammatory indices integrate signals from multiple cellular components and physiological processes affected by disease, providing a more comprehensive assessment than traditional single-marker approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Inflammatory Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Specifications | Research Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Hematology Analyzer | CBC with differential analysis | Precise quantification of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets | Fundamental for calculating all cellular ratios and indices [5] [35] |

| Clinical Chemistry Analyzer | Lipid panels, albumin, CRP quantification | Measurement of metabolic and inflammatory proteins | Essential for NHR (HDL-C), NPAR (albumin), CAR (CRP, albumin) [5] [34] [24] |

| ELISA/Kits | High-sensitivity CRP, IL-6, SAA, HBP | Quantification of specific inflammatory proteins | Traditional marker assessment; correlation studies [32] |

| Biobank Samples | Serum/plasma with linked clinical data | Longitudinal studies of biomarker trajectories | COVID-19 study with samples at multiple time points [32] |

| Statistical Software | R, SPSS, SAS with survival analysis packages | C-index, time-dependent AUC, multivariable regression | Prognostic accuracy assessment in iCCA study [33] |

| Piribedil | Piribedil, CAS:3605-01-4, MF:C16H18N4O2, MW:298.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Piribedil maleate | Piribedil maleate, CAS:937719-94-3, MF:C20H22N4O6, MW:414.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The accumulating evidence demonstrates that novel systemic inflammatory indices frequently outperform traditional markers in prognostic accuracy across diverse clinical contexts. The superior performance of these composite biomarkers likely stems from their ability to simultaneously capture multiple aspects of the immune-inflammatory response: innate immunity (via neutrophils, monocytes), adaptive immunity (via lymphocytes), coagulation/thrombosis (via platelets), and metabolic health (via HDL cholesterol or albumin) [5] [13] [34].

From a drug development perspective, these indices offer valuable tools for patient stratification in clinical trials, potentially enhancing enrollment criteria and providing sensitive endpoints for therapeutic efficacy. The differential performance of specific indices across disease states suggests that biomarker selection should be context-specific: NHR and related ratios incorporating lipid parameters show particular promise in metabolic-inflammatory conditions like HTG-AP [5], while PIV and SII demonstrate superior prognostic capabilities in oncology applications [33]. In psychiatric conditions, traditional NLR may retain advantage for specific outcomes like suicide risk assessment despite novel indices showing diagnostic utility [35].