Beyond Discovery: A Strategic Framework for Robust Clinical Validation of Novel Inflammatory Biomarkers

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to navigate the complex journey of clinically validating novel inflammatory biomarkers.

Beyond Discovery: A Strategic Framework for Robust Clinical Validation of Novel Inflammatory Biomarkers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to navigate the complex journey of clinically validating novel inflammatory biomarkers. It covers the foundational principles of biomarker types and roles in precision medicine, details rigorous methodological approaches for analytical and clinical validation, addresses common challenges in reproducibility and standardization, and explores advanced frameworks for regulatory qualification and comparative analysis against established markers. By synthesizing current best practices, regulatory insights, and emerging technological trends, this guide aims to elevate validation standards and accelerate the translation of promising inflammatory biomarkers into clinically useful tools.

Laying the Groundwork: From Biomarker Discovery to Clinical Rationale

Inflammation is a critical driver of many diseases, from cancer to autoimmune disorders. Biomarkers—measurable indicators of biological states—are essential tools for diagnosing, predicting outcomes, and selecting treatments in inflammatory conditions. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the challenges of biomarker research and improve the clinical validation of novel inflammatory biomarkers.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Pre-Analytical Variables and Sample Integrity

Q: My biomarker data shows high variability between replicates. What are the most common pre-analytical factors I should investigate?

High variability often originates from pre-analytical inconsistencies. The following table summarizes common lab issues and their solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Pre-Analytical Variability in Biomarker Research

| Issue | Potential Impact on Biomarker Data | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Improper Sample Handling [1] | Degradation of proteins/nucleic acids; unreliable results. | Implement standardized protocols for flash-freezing, consistent thawing on ice, and maintaining cold chain logistics [1]. |

| Inconsistent Sample Preparation [1] | Introduces bias in downstream analyses (e.g., sequencing, PCR). | Standardize extraction methods, use validated reagents, and implement rigorous quality control checkpoints [1]. |

| Sample Contamination [1] | False positives, skewed biomarker profiles, misleading signals. | Use dedicated clean areas, routine equipment decontamination, single-use consumables, and consider automated homogenization [1]. |

| Inadequate Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) [1] | High error rates and data irreproducibility between operators and batches. | Develop and enforce comprehensive SOPs, provide regular training, and implement barcoding systems to track samples and reagents [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Sample Preparation Consistency This protocol is designed to identify the source of pre-analytical variability in a protein-based cytokine assay [2].

- Sample Splitting: Split a single, large-volume patient serum or plasma sample into multiple aliquots.

- Variable Introduction: Process the aliquots with intentional, controlled variations:

- Group A: Process immediately after thawing.

- Group B: Leave at room temperature for 30 minutes before processing.

- Group C: Use different lots of the sample collection tube.

- Group D: Use two different technicians to perform the extraction.

- Analysis: Run all samples in the same multiplex cytokine assay (e.g., Luminex or ELISA) [2].

- Data Comparison: Measure the coefficient of variation (CV) across the different groups. A high CV in a specific group pinpoints the source of variability.

Diagnostic Biomarker Panels

Q: A single inflammatory cytokine lacks diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for my disease of interest. What is a more robust approach?

Single-cytokine tests often show limited clinical utility due to the complexity of inflammatory pathways. Combining multiple biomarkers into a panel significantly improves diagnostic performance [2].

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of Single vs. Combined Inflammatory Cytokines in Gastric Cancer [2]

| Biomarker | Change in GC vs. Control | Reported Diagnostic AUC | Key Limitations as a Single Marker |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Increased | 0.72 - 0.90 (varies by study) | Highly variable sensitivity (39%-85.7%) and specificity (50.1%-97%) across populations [2]. |

| IL-8 | Increased | 0.78 | Evidence can be mixed; some studies report no significant difference [2]. |

| IL-1β | Increased | ~0.70 | Low specificity (~43%) when used alone [2]. |

| IFN-γ | Increased | 0.65 (below 0.70) | May reflect general immune activation rather than tumor-specific presence [2]. |

| Multi-Cytokine Panel (e.g., IL-1β + IL-6 + IFN-γ) | - | 0.888 | Combinatorial panels better reflect complex immunobiology and offer superior accuracy [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Multiplex Cytokine Diagnostic Panel This methodology outlines the steps for creating and validating a composite biomarker panel [2] [3].

- Discovery Cohort: Use a multiplex assay (e.g., Luminex) to measure a broad panel of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α, etc.) in a well-characterized patient cohort and matched healthy controls [2].

- Statistical Modeling: Employ multivariable logistic regression or machine learning to identify the smallest combination of biomarkers that best distinguishes the groups. The output is a diagnostic algorithm.

- Validation: Apply this algorithm to an independent, blinded validation cohort to confirm its performance (AUC, sensitivity, specificity).

- Ascitic Fluid Analysis: For abdominal pathologies, measure biomarkers like CEA, CRP, IL-6, and VEGF directly in ascitic fluid, as this can offer better diagnostic insight than serum alone, especially when cytology is inconclusive [3].

Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker Applications

Q: How can I distinguish between a biomarker's prognostic and predictive value in the context of immunotherapy?

A prognostic biomarker provides information about a patient's overall cancer outcome, regardless of therapy. A predictive biomarker provides information about the benefit from a specific therapeutic intervention [4].

Table 3: Key Inflammatory Biomarkers in Cancer Prognosis and Treatment Prediction [4] [5]

| Biomarker | Role & Mechanism | Clinical/Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII, SIRI, NLR) [5] | Prognostic: Calculated from peripheral blood counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, monocytes), reflecting a pro-tumor systemic inflammatory state. | Elevated levels are strongly associated with worse overall survival in many solid tumors, including prostate cancer. For example, high SIRI was associated with a >6x increased risk of prostate cancer [5]. |

| PD-L1 Expression [4] | Predictive: Tumor cell overexpression of PD-L1 inhibits T-cell function. | Used to identify patients most likely to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) across various cancers [4]. |

| Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) [4] | Predictive: Higher TMB suggests more neoantigens, making tumors more visible to the immune system. | Patients with high-TMB tumors are more likely to benefit from immunotherapy [4]. |

| Microsatellite Instability (MSI) [4] | Predictive: A form of high TMB resulting from defective DNA mismatch repair. | A validated biomarker for predicting response to immunotherapy in multiple cancer types [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Correlating Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers with Clinical Outcomes

- Cohort Definition: Define a retrospective or prospective cohort of patients with a specific cancer and available baseline clinical data and blood counts.

- Index Calculation: Calculate systemic inflammatory indices (e.g., SII, NLR, PLR, SIRI) from routine blood test data [5].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Prognostic Analysis: Use Cox regression to assess the association between each index (categorized into quartiles) and Overall Survival (OS) or Progression-Free Survival (PFS).

- Predictive Analysis: In a cohort treated with immunotherapy, test for an interaction between the biomarker level and treatment effect on survival.

- Validation: Validate findings in an independent cohort to ensure robustness [5].

Biomarker Assay Validation and Reproducibility

Q: My experimental assay is producing unexpected results. What is a systematic way to troubleshoot this?

Apply a scientific troubleshooting framework to diagnose experimental problems efficiently [6].

- Define the Problem: Clearly state the expected result versus the observed result. (e.g., "My negative control is showing a positive signal.") [7].

- Gather Information & Develop Hypotheses: List all relevant details (reagent lot numbers, equipment used, technician, protocol version). Based on this, develop testable hypotheses (e.g., "The assay buffer is contaminated," "The plate reader was miscalibrated," "The detection antibody is degraded") [7] [6].

- Test Hypotheses Systematically: Test one variable at a time to isolate the cause. Start with the simplest and most likely explanation first (Occam's razor) [6].

- Hypothesis: Contaminated buffer. Test: Use a fresh, aliquoted batch of buffer from a different lot and repeat the control experiment.

- Hypothesis: Faulty equipment. Test: Run a known positive control sample on a different, properly calibrated plate reader.

- Analyze Results and Implement CAPA: Based on the test results, identify the root cause. Implement Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA), such as revising the SOP, adding a quality control step, or implementing mandatory equipment calibration logs [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Inflammatory Biomarker Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Multiplex Immunoassay Kits (Luminex) | Simultaneously measure concentrations of multiple cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ) from a single small-volume sample [2]. |

| ELISA Kits | Gold-standard for quantifying a specific protein (antigen) in a sample. Useful for validating results from multiplex assays [2]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | A comprehensive genomic test to assess predictive biomarkers like Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) and Microsatellite Instability (MSI) from tissue or liquid biopsy samples [4] [8]. |

| Programmed Cell Staining Kits (IHC/IF) | Antibodies for detecting protein expression of biomarkers like PD-L1 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue sections [4]. |

| Cell Separation Kits | Isolate specific immune cell populations (e.g., T cells, monocytes) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for functional studies. |

| Automated Homogenizer (e.g., Omni LH 96) | Standardizes the disruption of tissue samples, ensuring uniform extraction of proteins/nucleic acids while minimizing cross-contamination and variability [1]. |

| Mirosamicin | Mirosamicin, CAS:73684-69-2, MF:C37H61NO13, MW:727.9 g/mol |

| Okadaic Acid | Okadaic Acid, CAS:78111-17-8, MF:C44H68O13, MW:805.0 g/mol |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling

Inflammatory Cytokine Signaling in Cancer

This diagram illustrates how key pro-inflammatory cytokines contribute to tumor progression and therapy resistance, forming the biological basis for their use as biomarkers [2].

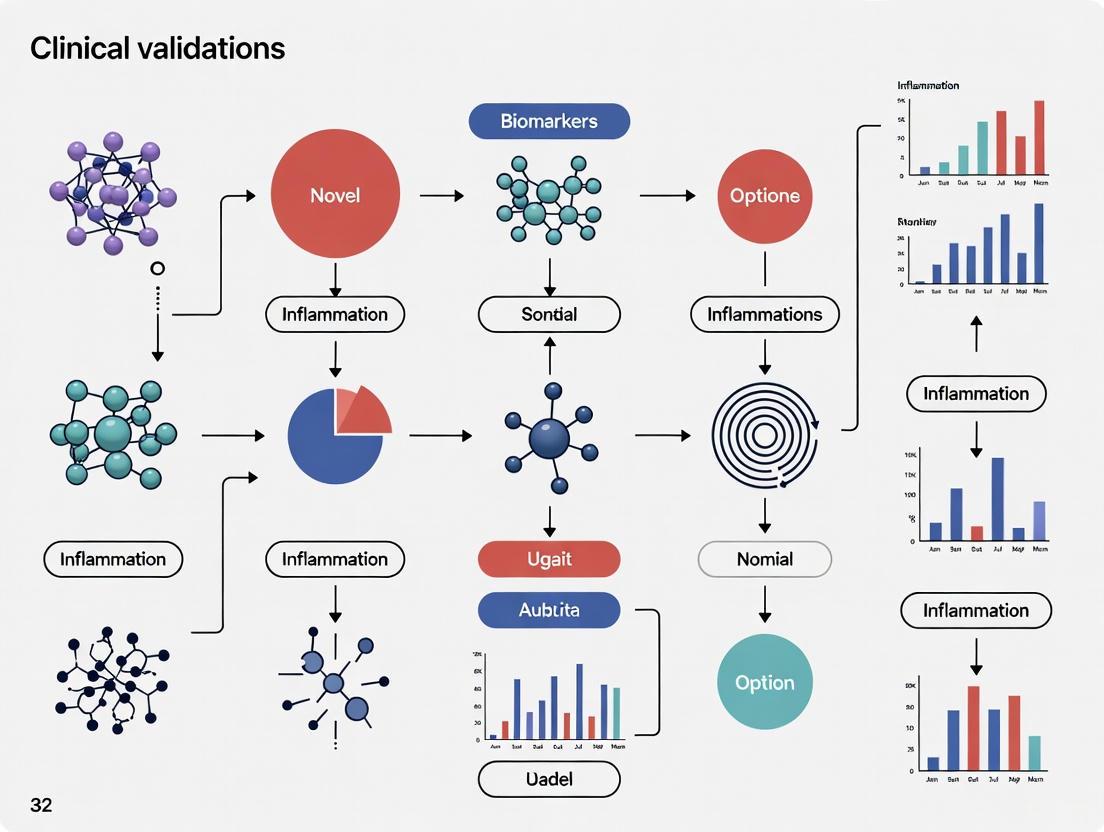

Biomarker Discovery and Validation Workflow

This flowchart outlines a generalized, multi-stage pathway for translating a candidate biomarker from initial discovery into clinical application.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Biomarker Validation Failures and Solutions

This guide addresses frequent challenges encountered during the validation of novel inflammatory biomarkers, providing targeted solutions to help researchers navigate the complex journey from discovery to clinical implementation.

Stage 1: Discovery and Assay Development

Problem: Candidate biomarkers fail during initial technical validation Symptoms: Inconsistent measurements, poor reproducibility across labs, inability to detect biomarker in different sample matrices. Solutions:

- Implement fit-for-purpose validation early, tailoring stringency to intended use [9].

- Use advanced platforms like LC-MS/MS or Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) which offer greater sensitivity and specificity than traditional ELISA [9].

- Establish standardized SOPs for sample collection, processing, and storage to minimize pre-analytical variability [1] [10].

Problem: Overfitting in biomarker discovery Symptoms: Excellent performance in initial cohort that disappears in independent validation. Solutions:

- Apply rigorous cross-validation methods with proper implementation to avoid inflated performance estimates [11].

- Use statistical methods like LASSO or elastic net that prevent overfitting during feature selection [11].

- Ensure adequate sample size during discovery (minimum 50-200 samples) to identify robust associations [12].

Stage 2: Analytical Validation

Problem: Poor reproducibility across sites Symptoms: Inter-lab variability with coefficients of variation exceeding acceptable thresholds (>15%). Solutions:

- Implement automated sample processing systems (e.g., Omni LH 96 homogenizer) to reduce manual variability [1].

- Establish rigorous quality control measures including standard reference materials [1] [10].

- Conduct interlaboratory studies early to identify sources of technical variability [12].

Problem: Inadequate sensitivity/specificity Symptoms: Cannot distinguish disease states with sufficient accuracy for clinical utility. Solutions:

- Consider multiplex platforms (e.g., MSD U-PLEX) that enable simultaneous measurement of multiple biomarkers, potentially improving classification accuracy [9].

- Evaluate alternative sample types or enrichment strategies to improve signal-to-noise ratio [10].

- Optimize assay conditions through systematic design of experiments (DOE) approaches [10].

Stage 3: Clinical Validation

Problem: Failure to generalize in diverse populations Symptoms: Performance degradation when applied to populations with different demographics, comorbidities, or genetic backgrounds. Solutions:

- Ensure representative patient recruitment from the beginning of validation studies [13] [14].

- Account for within-subject correlation in statistical models when multiple measurements are taken from the same patient [15].

- Test for effect modification by clinical covariates that might impact biomarker performance [13].

Problem: Confusing association with prediction Symptoms: Biomarker correlates with disease presence but cannot predict future outcomes. Solutions:

- Clearly distinguish between diagnostic and predictive claims during study design [13].

- Use prospective study designs for predictive biomarkers rather than retrospective analyses vulnerable to reverse causation [13].

- Ensure the outcome being predicted hasn't already occurred when the biomarker is measured [13].

Stage 4: Clinical Implementation

Problem: Demonstrating clinical utility Symptoms: Biomarker is analytically valid but doesn't change clinical decisions or improve patient outcomes. Solutions:

- Define specific clinical decision thresholds during validation rather than just statistical associations [12] [11].

- Conduct clinical utility studies showing how biomarker use changes management and improves outcomes [12] [16].

- Consider risk-benefit balance - sometimes negative prediction is more valuable than positive prediction depending on clinical context [13].

Problem: Regulatory challenges Symptoms: Inability to gain regulatory approval despite promising clinical data. Solutions:

- Engage regulators early through FDA Biomarker Qualification Program or EMA's Qualification of Novel Methodologies [12] [10].

- Provide comprehensive evidence of analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility [12] [9].

- Demonstrate superiority to existing standards or meaningful additive value to current clinical parameters [14].

Performance Standards and Metrics

Table 1: Key Analytical Validation Performance Requirements

| Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Precision (CV) | <15% for repeat measurements | Underestimating inter-operator variability |

| Sensitivity | Sufficient to detect clinically relevant levels | Not establishing LOD/LOQ in relevant matrix |

| Specificity | Demonstrate minimal cross-reactivity | Inadequate testing against related biomarkers |

| Dynamic Range | 80-120% recovery across range | Not validating at clinical decision points |

| Reproducibility | Consistent performance across sites | Inadequate standardization of protocols |

Table 2: Clinical Validation Statistical Requirements

| Metric | Minimum Threshold | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | ≥0.80 for clinical utility [12] | Higher thresholds needed for screening |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | Typically ≥80% depending on indication [12] | Balance depends on clinical context |

| Positive Predictive Value | Varies by disease prevalence | Often overlooked in validation studies |

| Likelihood Ratios | Provide clinical interpretability | More useful than sensitivity/specificity alone |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Inflammatory Biomarker Validation

| Reagent Type | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Immunoassay Panels (e.g., MSD U-PLEX) | Simultaneous measurement of multiple inflammatory mediators | More cost-effective than individual ELISAs; $19.20 vs $61.53 per sample for 4-plex [9] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance over time | Should mimic patient sample matrix |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and harmonization across sites | Often overlooked in early development |

| Sample Collection & Stabilization Systems | Preserve biomarker integrity during collection | Critical for labile inflammatory markers |

| Automated Homogenization Systems | Standardize sample preparation | Reduce contamination risk and increase efficiency by up to 40% [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Critical Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Interlaboratory Reprodubility Study Purpose: Demonstrate consistent performance across multiple sites. Procedure:

- Distribute identical aliquots of 20-30 well-characterized samples to participating laboratories

- Include samples spanning clinical range and controls

- Each site performs measurements in duplicate over 3 separate days

- Analyze results using mixed effects models to partition variability components [15] Key Parameters: Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC >0.9 excellent), inter-site CV (<15%)

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Stability Assessment Purpose: Establish test-retest reliability for monitoring biomarkers. Procedure:

- Collect serial samples from stable patients (n=minimum 40) over biologically relevant time frame

- Analyze using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) appropriate for study design [11]

- Calculate minimum detectable difference to establish sensitivity to change

- Compare to minimal clinically important difference Key Parameters: ICC (select appropriate version based on design [11]), within-subject variance

Protocol 3: Clinical Specificity Evaluation Purpose: Determine biomarker performance in differential diagnosis. Procedure:

- Recruit patients with target condition and relevant differential diagnoses

- Measure biomarker in all groups (minimum 50 per group)

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios

- Perform ROC analysis with confidence intervals Key Parameters: Area under ROC curve, positive/negative predictive values, likelihood ratios

Workflow Visualization

Biomarker Validation Pipeline

Statistical Considerations for Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between biomarker validation and qualification? A: Validation is the scientific process of generating evidence that a biomarker is reliable and clinically meaningful, typically taking 3-7 years and resulting in peer-reviewed publications. Qualification is the regulatory process where the FDA or EMA formally recognizes the biomarker for specific uses in drug development, taking 1-3 years and resulting in official qualification letters [12].

Q: Why do over 95% of biomarker candidates fail to reach clinical use? A: Most failures occur due to lack of analytical robustness (assays work in one lab but not others), inadequate clinical validation (failure to generalize across diverse populations), and insufficient clinical utility (doesn't change patient management or outcomes) [17] [12]. Other common reasons include overfitting in discovery, confounding in clinical studies, and inadequate attention to pre-analytical variables [16].

Q: What statistical considerations are most frequently overlooked in biomarker validation? A: Four key issues are commonly neglected: (1) Failure to account for within-subject correlation when multiple measurements come from the same patient; (2) Inadequate control for multiple testing, increasing false discovery rates; (3) Confusing statistical significance with classification accuracy; (4) Selection bias in retrospective studies [15] [11].

Q: How do I determine the appropriate sample size for biomarker validation studies? A: Sample size should be determined by the intended use and required precision. For classification biomarkers, sample size calculations should be based on the probability of classification error rather than just p-values. For reliability studies, much larger sample sizes are needed than for simple group comparisons - often requiring hundreds to thousands of participants depending on the clinical context [11].

Q: When should I transition from traditional ELISA to more advanced platforms like MSD or LC-MS/MS? A: Consider advanced platforms when you need: greater sensitivity for low-abundance biomarkers, multiplexing capability to measure multiple biomarkers simultaneously, broader dynamic range, or when ELISA development is proving challenging due to matrix effects or antibody limitations. The cost savings of multiplexing can be substantial - up to 70% reduction compared to multiple ELISAs [9].

Q: What are the most common reasons regulators reject biomarker submissions? A: A review of EMA biomarker qualifications found that 77% of challenges were linked to assay validity issues, particularly problems with specificity, sensitivity, detection thresholds, and reproducibility [9]. Other common issues include inadequate demonstration of clinical utility and failure to show superiority over existing standards.

Q: How can I demonstrate clinical utility for an inflammatory biomarker? A: Clinical utility requires evidence that using the biomarker improves patient outcomes or decision-making compared to standard care. This can be shown through: (1) Clinical trials where biomarker-guided therapy demonstrates better outcomes; (2) Change in management studies showing clinicians alter treatment based on results; (3) Health economic analyses demonstrating improved efficiency or reduced costs [12] [16].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary purpose of establishing a clinical rationale for a novel inflammatory biomarker? The primary purpose is to demonstrate the biomarker's biological and clinical relevance by definitively linking it to a specific disease mechanism. This establishes the biomarker's value in addressing an unmet clinical need, such as early disease detection, predicting treatment response, or stratifying patient populations for more effective and targeted therapies [18].

Q2: My biomarker shows strong statistical association with a disease in my cohort. Is this sufficient for clinical validation? A strong statistical association is a crucial first step, but it is not sufficient for full clinical validation. The biological plausibility of the link must be established by elucidating the mechanism of action. Furthermore, you must demonstrate the biomarker's clinical utility by showing how it addresses a specific unmet need, such as diagnosing a condition earlier than current standards, identifying patients who will respond to a specific therapy, or monitoring disease progression more accurately [18].

Q3: What are the key methodological challenges in linking a biomarker to a disease mechanism? Key challenges include:

- Biological Specificity: Distinguishing whether the biomarker is a direct driver of the pathology or a secondary consequence of another process.

- Analytical Validation: Ensuring the assay used to measure the biomarker is robust, reproducible, and accurate across different sample types and laboratories [18].

- Patient Heterogeneity: Accounting for variability in biomarker expression due to genetic diversity, co-morbidities, or environmental factors [19].

Q4: How can I strengthen the evidence for a causal relationship between my biomarker and the disease? Evidence can be strengthened through a multi-faceted approach:

- Experimental Models: Using in vitro (e.g., cell cultures) and in vivo (e.g., animal models) systems to manipulate the biomarker and observe direct effects on disease-relevant pathways.

- Multi-Omics Integration: Correlating your biomarker data with genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic datasets to place it within a broader biological context [19].

- Clinical Corroboration: Utilizing samples from well-characterized patient cohorts and, where possible, leveraging longitudinal studies to show that changes in the biomarker level precede clinical manifestations of the disease [18].

Q5: What regulatory considerations are critical for biomarker validation in rare inflammatory diseases? For rare diseases, regulators like the FDA acknowledge the challenges of small patient populations. Key considerations include:

- Innovative Trial Designs: Utilizing single-arm trials, Bayesian statistics, and master protocols to maximize data from limited patients [20].

- Use of Real-World Evidence (RWE): Incorporating data from registries and electronic health records to support clinical evidence, provided data reliability and relevance are rigorously addressed [20].

- Clear Biomarker Context of Use: Precisely defining the biomarker's intended role (e.g., prognostic, predictive, pharmacodynamic) in the drug development process [20].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: In Vitro Functional Validation of a Novel Inflammatory Biomarker

Objective: To establish a causal link between the biomarker and a key inflammatory pathway in a controlled cell culture system.

Materials and Workflow:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Vitro Validation

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Primary Human Macrophages | Representative human immune cells for studying inflammatory responses in a physiologically relevant model. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A potent inflammatory stimulant used to induce a consistent state of inflammation in the cell culture system. |

| Biomarker-Specific siRNA | Silences the gene encoding the target biomarker to investigate the functional consequences of its knockdown. |

| Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody | Binds to and blocks the activity of the soluble biomarker protein, allowing assessment of its specific role. |

| Phospho-Specific NF-κB Antibody | Detects activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of inflammation, via Western Blot. |

Protocol 2: Clinical Correlational Analysis in Patient Cohorts

Objective: To validate the association between the novel biomarker and established clinical metrics of disease activity and unmet needs.

Materials and Workflow:

Table 2: Key Materials for Clinical Cohort Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Validated Immunoassay Kit (ELISA) | Provides a standardized, quantitative method for accurately measuring biomarker concentration in patient serum/plasma. |

| Luminex xMAP Technology | Allows for the multiplexed measurement of the novel biomarker alongside dozens of other analytes from a single small sample volume. |

| Clinical Data Collection Form (CRF) | A standardized document for systematically capturing all relevant patient data, ensuring consistency and quality for analysis. |

| Biobanked Patient Samples | Well-annotated, high-quality samples from retrospective cohorts that can be used for initial discovery and validation studies. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 3: Framework for Summarizing Quantitative Biomarker-Disease Links

| Evidence Category | Experimental Method | Key Quantitative Metric(s) | Interpretation & Link to Unmet Need |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association | Correlation Analysis | Correlation coefficient (r), p-value | Strength of relationship between biomarker and disease activity. |

| Diagnostic Accuracy | Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis | Area Under Curve (AUC), Sensitivity, Specificity | Ability to distinguish patients from healthy controls or other diseases. |

| Predictive Value | Cox Proportional-Hazards Regression | Hazard Ratio (HR), Confidence Interval (CI) | Ability to forecast clinical outcomes like flare-ups or progression. |

| Therapeutic Response | Longitudinal Mixed Models | Mean change from baseline, p-value vs. placebo | Utility in monitoring and predicting response to treatment. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Validation

| Category | Item | Brief Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Stabilizes intracellular RNA for transcriptomic biomarker analysis from whole blood. |

| Detection & Assay | MSD MULTI-SPOT Assay Plates | Electrochemiluminescence platform for sensitive, multiplexed protein biomarker detection. |

| Signal Transduction | Phospho-Kinase Array Kit | Simultaneously monitor the relative phosphorylation levels of multiple key kinase pathways. |

| Data Analysis | R/Bioconductor Packages (e.g., limma) |

Open-source statistical tools for rigorous analysis of high-throughput biological data. |

| Model Organisms | Transgenic Mouse Models | Genetically engineered to overexpress or lack the biomarker gene for in vivo functional studies. |

| Olaquindox | Olaquindox|Antimicrobial Research Compound|RUO | |

| Mivazerol | Mivazerol, CAS:125472-02-8, MF:C11H11N3O2, MW:217.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The clinical validation of novel inflammatory biomarkers is a cornerstone of precision medicine, yet its success is heavily dependent on processes that occur before analysis even begins. The pre-analytical phase—encompassing everything from patient preparation to sample storage—is the most vulnerable stage in the laboratory testing process. Research indicates that 60-75% of laboratory errors originate in the pre-analytical phase, with significant implications for data integrity, reproducibility, and clinical validity [21] [22] [23]. For inflammatory biomarker research specifically, pre-analytical conditions can alter biomarker levels, potentially obscuring true biological signals and compromising research outcomes [24]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and standardized protocols to help researchers maintain sample integrity throughout the pre-analytical workflow, thereby enhancing the reliability of their inflammatory biomarker studies.

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Pre-Analytical Challenges

Hemolysis: Identification and Prevention

Problem: Hemolyzed samples are the most frequent pre-analytical issue, accounting for 40-70% of all pre-analytical errors [22] [25]. Hemolysis causes spurious release of intracellular analytes (potassium, phosphate, magnesium, LDH, AST, ALT) and can interfere with analytical methods through spectral interference.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Visually inspect samples for pink-to-red discoloration in serum or plasma. However, note that visual detection is only possible at free hemoglobin concentrations >0.2-0.3 g/L [25].

- Identify the source: Most hemolysis (>98%) occurs in vitro due to collection and handling issues [21].

- Implement preventive measures:

- Minimize tourniquet time (aim for <1 minute) [21].

- Use appropriately sized needles to avoid excessive vacuum [21].

- Ensure disinfectant alcohol has completely dried before venipuncture [21].

- Avoid transferring blood from a syringe to a sample tube through a needle [21].

- Mix collection tubes by gentle inversion only—never shake [21].

- Centrifuge samples promptly after collection clot formation (for serum) [25].

Sample Misidentification and Labeling Errors

Problem: Patient misidentification and improper tube labeling account for a significant portion of pre-analytical errors, creating critical risks for patient safety and data integrity [22].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use at least two patient identifiers (e.g., full name and date of birth) to confirm identity before collection [21] [22].

- Label tubes in the presence of the patient after collection to prevent mix-ups. Avoid pre-labeling tubes before drawing blood [21].

- Implement automated identification systems where possible, such as barcoding, which has been shown to reduce mislabeling incidents by up to 85% [1] [22].

Improper Sample Collection Timing

Problem: Collection at incorrect timepoints can skew results for biomarkers with diurnal variation or those affected by metabolic state.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Consider circadian rhythm: Hormones like cortisol and renin exhibit strong diurnal variation. For inflammatory biomarkers, consistency in collection time across study participants is crucial [21].

- Standardize fasting status: While not all tests require fasting, markers like glucose and triglycerides are profoundly affected. A 10-12 hour fast is standard, but prolonged fasting (>16 hours) should be avoided [21] [22].

- Document timing accurately: Record the time of collection and, for therapeutic drug monitoring, the time of last drug administration [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the maximum allowable "needle-to-freezer" time for inflammatory biomarker studies?

A: Stability is analyte-specific, but a rapid turnaround is universally recommended. General guidelines suggest separating plasma or serum from cells within 1-2 hours of collection [24] [25]. A 2025 study on inflammation biomarkers found that while many proteins in the Olink Target 96 Inflammation panel were stable across various processing times, delays affected age-related associations for some biomarkers. When possible, standardize processing protocols across all study samples and process immediately for optimal results [24].

Q2: For plasma-based inflammatory biomarkers, which anticoagulant is most appropriate?

A: The choice of anticoagulant is critical and depends on your analytical platform:

- EDTA-plasma: Preferred for most immunochemistry assays and hematology parameters [25].

- Heparin-plasma: Suitable for clinical chemistry and some immunochemistry tests, but can interfere with mass spectrometry and peptide analyses [25].

- Citrate-plasma: Primarily used for coagulation studies, but may be used for other assays with a correction factor [25].

- Serum: Traditionally used for many clinical chemistry tests, but the clotting process can alter the protein profile compared to plasma [25].

Q3: How do repeated freeze-thaw cycles affect inflammatory biomarkers?

A: Multiple freeze-thaw cycles can cause protein degradation or aggregation, leading to inaccurate measurements. Studies indicate that even a single freeze-thaw cycle can affect concentrations of sensitive biomarkers [23]. To minimize this effect:

- Aliquot samples before initial freezing into single-use volumes.

- Establish a standard operating procedure that documents the maximum allowable freeze-thaw cycles for your study (typically 1-3 cycles).

- Maintain detailed records of the freeze-thaw history for each sample [23].

Q4: What strategies can help minimize patient blood loss in longitudinal studies?

A: Patient blood management is especially important in studies requiring repeated sampling. Effective strategies include:

- Using low-volume or pediatric blood collection tubes to reduce draw volume [26].

- Consolidating test requests to avoid unnecessary duplicate testing [26].

- Implementing microsampling techniques or point-of-care testing where possible [26].

The following tables summarize key quantitative data on pre-analytical errors and their impacts, essential for risk assessment and quality control planning in biomarker research.

Table 1: Distribution of Laboratory Errors by Phase

| Testing Phase | Percentage of Total Errors | Common Error Types |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Analytical | 60% - 75% | Improper sample collection, misidentification, incorrect timing, improper handling [27] [22] [23] |

| Analytical | 7% - 13% | Equipment malfunction, undetected quality control failures [21] [22] |

| Post-Analytical | Not Specified | Test result loss, erroneous validation, transcription errors [22] |

Table 2: Frequency of Specific Pre-Analytical Problems

| Pre-Analytical Issue | Frequency (% of Pre-Analytical Errors) | Primary Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Hemolysis | 40% - 70% | False elevation of intracellular analytes (K+, LDH, AST); spectral interference [22] [25] |

| Insufficient Sample Volume | 10% - 20% | Inability to perform tests; need for recollection [22] |

| Clotted Sample (in anticoagulant tubes) | 5% - 10% | Invalid results for hematology and coagulation tests [22] |

| Improper Container | 5% - 15% | Anticoagulant contamination; incorrect sample matrix [22] |

Table 3: Impact of Pre-Analytical Delays on Inflammation Biomarker Stability [24]

| Stability Metric | Percentage of Proteins Affected | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins with good-excellent correlation (across protocols) | 38% - 83% | A majority of inflammation biomarkers show robustness to variations in pre-analytical processing. |

| Proteins with significant concentration change (>0.5 NPX units) | 18 proteins identified | A subset of biomarkers is highly sensitive to pre-analytical conditions and requires strict protocol adherence. |

| Age-related associations lost due to processing delays | 40% (12 of 30 significant associations) | Pre-analytical variability can obscure biologically significant relationships in epidemiological research. |

Experimental Protocols for Pre-Analytical Validation

Protocol: Evaluating Sample Stability Over Time

Objective: To determine the stability of specific inflammatory biomarkers under different handling conditions before processing.

Materials:

- Blood collection tubes (e.g., Serum, EDTA-plasma, Heparin-plasma)

- Centrifuge

- Refrigerator (4°C)

- Freezer (-80°C)

- Appropriate biomarker analysis platform (e.g., multiplex immunoassay)

Methodology:

- Collect blood from a minimum of 5 healthy volunteers into multiple tube types.

- For each tube type, aliquot whole blood samples and hold them at room temperature for the following time intervals: 0 hours (immediate processing), 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, 8 hours, and 24 hours.

- After each time interval, centrifuge the samples according to standard protocols (e.g., 1500-2000 x g for 10-15 minutes) and aliquot the serum/plasma.

- Store all aliquots at -80°C until batch analysis.

- Analyze all samples from the same donor in the same batch to minimize analytical variance.

- Calculate the percentage change in biomarker concentration relative to the 0-hour baseline for each time point. A change greater than the assay's total allowable error or a statistically significant trend indicates instability.

Protocol: Assessing Freeze-Thaw Stability

Objective: To establish the maximum number of freeze-thaw cycles for specific inflammatory biomarkers.

Materials:

- Previously aliquoted serum or plasma samples

- Freezer (-80°C)

- Water bath or refrigerator for thawing

Methodology:

- Select a pool of well-characterized serum or plasma samples with known concentrations of your target biomarkers.

- Subject aliquots to sequential freeze-thaw cycles (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 5 cycles). One cycle consists of thawing samples completely at 4°C (or room temperature, standardized) and then re-freezing at -80°C for a minimum of 4 hours.

- Include a control aliquot that is thawed only once alongside the maximally cycled samples.

- Analyze all samples in the same batch.

- Compare the measured concentration after each cycle to the control. A significant change (e.g., >10-15%) indicates degradation.

Visual Workflows and Logical Diagrams

Pre-Analytical Workflow for Inflammatory Biomarker Research

The following diagram outlines the critical decision points and standardized procedures in the pre-analytical phase to ensure sample quality for inflammatory biomarker research.

Sample Provenance and Tracking Logic

This diagram visualizes the chain of custody and information flow required to maintain sample provenance from collection to analysis, which is critical for clinical validation studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Analytical Work

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Inhibits coagulation by chelating calcium. Preferred for plasma and many immunoassays. | Prevents clotting; chelation can interfere with some metal-dependent assays. [21] [25] |

| Serum Separator Tubes (SST) | Contains a gel and clot activator for serum preparation. | Allows for clean serum separation; clotting time must be standardized (30-60 mins). [25] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to collection tubes to prevent proteolytic degradation of protein biomarkers. | Critical for unstable biomarkers (e.g., ANP, BNP); requires validation. [25] |

| Low-Bind Microcentrifuge Tubes | For sample aliquoting and storage. Minimizes protein adhesion to tube walls. | Essential for low-abundance biomarkers to prevent analyte loss. [23] |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Internal Standards | Used in mass spectrometry-based assays to correct for pre-analytical and analytical variability. | Distinguishes true biomarker changes from artifacts introduced during sample handling. [25] |

| Automated Homogenization Systems | Standardizes sample preparation (e.g., Omni LH 96). | Reduces human error and cross-contamination; increases throughput and reproducibility. [1] |

| Olsalazine | Olsalazine for Research|Anti-inflammatory Compound | Olsalazine is a prodrug of mesalazine for inflammatory bowel disease research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Omapatrilat | Omapatrilat | Omapatrilat is a dual ACE/NEP inhibitor for cardiovascular research. This product is for research use only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

Executing Rigorous Validation: Assays, Metrics, and Study Design

For researchers and scientists focused on the clinical validation of novel inflammatory biomarkers, establishing robust analytical methods is a critical step. The reliability of your data, and ultimately the success of your biomarker's translation to clinical use, hinges on a fundamental understanding of three core principles: Sensitivity, Specificity, and Reproducibility. This technical support guide provides clear, actionable protocols and troubleshooting advice to help you assess these parameters effectively, ensuring your analytical methods are fit-for-purpose and generate reliable, defensible data.

Core Principles and Definitions

Before embarking on experimental work, it is crucial to define the key performance characteristics of your analytical method.

- Sensitivity, often referred to as the Limit of Detection (LOD), is the lowest concentration of an analyte that an analytical procedure can reliably detect. It represents the capability of a method to detect trace levels of a biomarker [28] [29].

- Specificity is the ability of the method to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix, such as other proteins, metabolites, or interfering substances [30] [28] [31]. For biomarker assays, this ensures that the signal measured is due to the target biomarker and not a cross-reacting entity.

- Reproducibility expresses the precision of the method under normal operational conditions and is a measure of its reliability. It is the degree of agreement between the results of measurements conducted on the same homogeneous sample in different laboratories, by different analysts, using different equipment, and over extended time periods [30] [28]. It is often subdivided into:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

This protocol outlines the experimental methodology for determining the LOD of your biomarker assay.

1. Principle The LOD is determined by establishing the lowest concentration of the biomarker that can be consistently distinguished from a blank sample. A common approach is based on the signal-to-noise ratio, where the analyte response is compared to the background noise of the system [29] [31].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Reference Standard: Purified and well-characterized target biomarker.

- Assay Buffer: The matrix-matching buffer used in your analytical procedure.

- Sample Matrix: The biological fluid relevant to your biomarker (e.g., serum, plasma) from which the analyte has been stripped or confirmed to be absent.

- Required Equipment: The full analytical instrumentation (e.g., HPLC system, plate reader, PCR cycler) as specified in your method.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Prepare a series of analyte samples at concentrations near the expected LOD. A minimum of 5 concentration levels is recommended.

- Step 2: Prepare a minimum of 20 replicates of a blank sample (matrix without the analyte) [29].

- Step 3: Analyze all samples (low concentrations and blanks) using the validated analytical method.

- Step 4: Measure the response for each sample.

4. Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria

- Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of the responses from the 20 blank replicates.

- The LOD is typically calculated as a concentration that provides a signal-to-noise ratio of 2:1 or 3:1. Alternatively, it can be derived statistically using the formula: LOD = 3.3 × (SD of the blank response / Slope of the calibration curve) [32].

- Acceptance Criterion: The determined LOD should be at or below the concentration required to detect the biomarker in its pathophysiological range.

Protocol 2: Establishing Analytical Specificity

This protocol is designed to confirm that your method is specific for the target inflammatory biomarker.

1. Principle Specificity is demonstrated by showing that the method can distinguish and quantify the biomarker in the presence of other components, such as related biomarkers, potential metabolites, and the sample matrix itself [31]. For stability-indicating methods, specificity is also demonstrated by analyzing samples that have been subjected to stress conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) [31].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Target Analyte: Your novel inflammatory biomarker.

- Interferents: A panel of structurally similar compounds, common metabolites, and known cross-reactive substances.

- Stressed Samples: Biomarker samples that have been subjected to forced degradation.

- Spiked Matrix Samples: Blank matrix spiked with the target biomarker and potential interferents.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Inject a blank or diluent solution to check for interference [31].

- Step 2: Separately inject solutions of each potential interferent.

- Step 3: Inject a solution of the target biomarker (standard).

- Step 4: Inject a spiked solution containing the target biomarker and all potential interferents at their expected concentrations [31].

- Step 5: (For stability-indicating methods) Inject samples of the biomarker that have been stressed under various conditions.

4. Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria

- Compare the chromatograms or assay readouts from all injections.

- Acceptance Criteria:

- There should be no interference from the blank at the retention time or detection channel of the target biomarker [31].

- The peak or signal for the target biomarker should be baseline-resolved from peaks or signals of any potential interferent [31].

- For chromatographic methods, peak purity assessment (e.g., using a photodiode array detector) should confirm that the main peak is homogeneous and pure [31].

Protocol 3: Assessing Reproducibility

This protocol evaluates the precision of your method across different runs, operators, and instruments.

1. Principle Reproducibility is assessed by analyzing multiple aliquots of the same homogeneous sample under varied but defined conditions and statistically analyzing the results [30] [28].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Homogeneous Sample: A single, well-mixed batch of sample containing the biomarker at a concentration within the quantitative range (typically low, mid, and high levels).

- Multiple Analysts: At least two qualified analysts.

- Multiple Instruments: If available, more than one instrument of the same model.

- Multiple Days: The study should be conducted over several days.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Prepare a homogeneous sample pool at a specified concentration.

- Step 2: Have Analyst 1 analyze a minimum of 6 replicates of the sample on Instrument A on Day 1.

- Step 3: Have Analyst 2 analyze another set of 6 replicates of the same sample on Instrument A (or Instrument B) on Day 2.

- Step 4: Ensure that the analytical procedure is followed identically by both analysts.

4. Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria

- Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and percent relative standard deviation (%RSD) for the results from each analyst/run.

- Use analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the results generated by different analysts or on different days.

- Acceptance Criterion: The inter-assay %RSD for reproducibility should be within predefined limits justified by the intended use of the assay. For many bioanalytical methods, an %RSD of ≤15% is often considered acceptable, with more stringent criteria required for critical quality attributes.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the difference between specificity and selectivity?

- Specificity deals with the separation of the peak (or signal) of interest from adjacent components. It ensures there is no interference with your target analyte [31].

- Selectivity deals with the separation between all components in a chromatogram or assay. An assay method is specific, whereas a related substance method is selective because it must resolve all impurities from each other and the main peak [31].

Q2: Our method's reproducibility is poor between two analysts. What could be the cause? Poor reproducibility often points to a method that is not sufficiently robust. Common culprits include:

- Insufficiently Detailed Procedure: Ambiguities in the method protocol that lead to different interpretations (e.g., "vortex briefly" vs. "vortex for 30 seconds at 2000 rpm").

- Variable Sample Preparation: Differences in techniques for steps like pipetting, mixing, or incubation timing.

- Environmental Factors: Uncontrolled room temperature or humidity.

- Solution: Conduct a robustness study during method development to identify critical parameters. Then, tightly control these parameters and specify them explicitly in the written procedure [30] [33].

Q3: How do I demonstrate specificity for a biomarker in a complex matrix like serum? The most effective way is through a spike-and-recovery experiment with interferents:

- Prepare a blank serum sample.

- Prepare a serum sample spiked only with your target biomarker.

- Prepare serum samples spiked with your target biomarker and high concentrations of potential interferents (e.g., related inflammatory cytokines, albumin, immunoglobulins).

- Analyze all samples. The measured concentration of the biomarker in the presence of interferents should be within an acceptable range (e.g., 85-115%) of the concentration measured in the sample without added interferents [31].

Q4: When should method validation be performed? Method validation is required:

- Prior to the use of the method in ongoing or routine testing [34].

- When the method is part of a regulatory submission (e.g., NDA, ANDA) [30] [34].

- When there are changes to previously validated conditions or method parameters that are outside the original validation scope [34].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | - Contaminated reagents or buffers.- Dirty instrument optics or flow cell.- Non-specific binding in immunoassays. | - Prepare fresh reagents and use high-purity water.- Perform instrument maintenance as per SOP.- Optimize blocking conditions or include a more specific detergent. |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Runs | - Uncontrolled variation in a critical method parameter (e.g., temperature, pH).- Instability of reagents or analytical standards.- Column degradation in chromatography. | - Perform a robustness study to identify and control key parameters [30].- Document reagent and standard stability and adhere to expiration dates.- Monitor system suitability criteria before each run [32]. |

| Inconsistent Sensitivity (LOD) | - Deterioration of detection source (e.g., lamp in HPLC).- Inconsistent sample preparation technique.- Matrix effects suppressing or enhancing the signal. | - Check and replace consumable instrument parts as needed.- Standardize and meticulously document sample prep steps.- Use a matrix-matched calibration curve and consider stable isotope-labeled internal standards. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for successful analytical validation experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Serves as the primary benchmark for establishing method accuracy, preparing calibration curves, and determining sensitivity. Its purity and characterization are foundational [34]. |

| Stripped/Blank Matrix | Essential for assessing specificity (by testing for interference) and for preparing calibration standards and quality control samples in spike-and-recovery experiments to determine accuracy. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (for LC-MS) | Corrects for variability in sample preparation, matrix effects, and instrument response, thereby significantly improving the precision and accuracy of the method. |

| Critical Reagents (e.g., Antibodies, Enzymes) | The quality and specificity of these reagents (especially for immunoassays or enzymatic assays) directly determine the method's specificity, sensitivity, and overall robustness. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Analytical Method Validation Workflow

Relationship Between Validation Parameters

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: High Background Signal in MSD Assays

Question: What are the common causes of a high background signal in Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) assays, and how can I resolve them?

Answer: High background is frequently traced to insufficient washing, which fails to remove unbound reagents. To resolve this, ensure thorough washing by increasing the number of wash cycles and incorporating a 30-second soak step between washes to improve the removal of unbound components [35]. Contaminated buffers or reagents can also cause high background; prepare fresh buffers for each experiment [35].

FAQ: Poor Duplicates and Assay Reproducibility

Question: My assays are showing poor duplicate reproducibility. What steps can I take to improve consistency?

Answer: Poor duplicates often result from uneven plate washing or coating. For automated plate washers, check that all ports are clean and unobstructed. Incorporate a soak step and rotate the plate halfway through the washing process [35]. Ensure consistent plate coating by using dedicated ELISA plates (not tissue culture plates) and diluting capture antibodies in PBS without additional protein. Always use fresh plate sealers for each incubation step to prevent cross-contamination from residual HRP enzymes [35].

FAQ: No Signal or Weak Signal When Expected

Question: I am not detecting a signal in my MSD assay, even though I know my sample contains the analyte. What could be wrong?

Answer: First, verify that all reagents were added in the correct order and were prepared correctly according to the protocol [35]. The standard or detection antibody may have degraded; prepare a new standard from a fresh vial and confirm antibody concentrations. If the standard curve appears normal but sample signals are weak, the sample matrix may be interfering with detection. Try diluting your samples at least 1:2 in an appropriate diluent, or perform a dilution series to check for recovery issues [35]. For low-abundance biomarkers, consider switching to an ultra-sensitive platform like the MSD S-PLEX, which can reduce the lower limit of detection by 10- to 1000-fold compared to other methods [36].

FAQ: Platform Selection for Biomarker Analysis

Question: How do I choose between Luminex and MSD platforms for my biomarker study?

Answer: The choice depends on your study's context of use, required sensitivity, and multiplexing needs. The table below compares the two platforms:

| Feature | Luminex Platform | MSD Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Technology | Fluorescence-labeled microspheres (xMAP) [37] | Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) with carbon electrodes [36] [37] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (up to 80 targets) [37] | Moderate (typically up to 10 targets) [37] |

| Sensitivity | Good | Superior (e.g., S-PLEX kits can detect biomarkers at femtogram levels) [37] |

| Dynamic Range | Good | Broad dynamic range [36] [37] |

| Ideal Use Case | Early-stage, high-throughput studies requiring a broad panel of targets [37] | Detecting low-abundance analytes in clinical or late-phase samples [37] |

For studies requiring the highest sensitivity for low-abundance inflammatory biomarkers, the MSD S-PLEX platform is often the preferred choice [36] [37].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: MSD S-PLEX Assay for Inflammatory Cytokines

Context of Use: This protocol is designed for the ultra-sensitive quantification of low-abundance inflammatory cytokines in human serum or plasma to support clinical validation studies [36].

Materials:

- MSD S-PLEX Assay Kit: Contains pre-coated multi-array plates, detection antibodies, and read buffer [36].

- MSD Instrumentation: Imager 6000, Sector S 600, or QuickPlex SQ 120 systems [36].

- SULFO-TAG Labels: Electrochemiluminescent labels conjugated to detection antibodies [36].

- Tripropylamine-containing Buffer: Catalyst for the electrochemical reaction [36].

- Pipettes and Microplates: For precise liquid handling.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the key steps and detection mechanism of the MSD S-PLEX assay workflow:

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Use the MSD multi-array plate pre-coated with capture antibodies.

- Sample & Incubation: Add standards, controls, and samples to the plate wells. Incubate to allow analyte binding to the capture antibody.

- Detection Antibody: Add a biotinylated detection antibody and incubate.

- SULFO-TAG Streptavidin: Add SULFO-TAG labeled streptavidin, which binds to the biotinylated detection antibody [36].

- Signal Detection: Add MSD Read Buffer containing Tripropylamine. Apply an electric current to the plate electrodes, exciting the SULFO-TAG labels and causing them to emit light at 620 nm. The instrument measures the light intensity, which is quantitatively proportional to the amount of analyte present [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| MSD S-PLEX or V-PLEX Kits | Pre-configured, validated assay kits for specific biomarker panels (e.g., inflammatory cytokines), providing high sensitivity and multiplexing capability [36]. |

| SULFO-TAG Labels | Electrochemiluminescent labels conjugated to detection antibodies; emit light upon electrical stimulation, enabling ultra-sensitive detection with low background [36]. |

| Carbon Electrode Microplates | Specialized plates used in the MSD platform. The electrodes at the bottom initiate the ECL reaction, and the high-binding carbon surface enhances antibody immobilization [37]. |

| Read Buffer with Tripropylamine (TPA) | A crucial chemical catalyst in the ECL buffer that participates in the redox reaction with Ruthenium in the SULFO-TAG, leading to light emission [36]. |

| Luminex xMAP Microspheres | Fluorescent-coded beads that allow for the simultaneous detection of multiple analytes in a single well, ideal for high-plex screening panels [37]. |

| Ombrabulin | Ombrabulin, CAS:181816-48-8, MF:C21H26N2O6, MW:402.4 g/mol |

| Onalespib | Onalespib, CAS:912999-49-6, MF:C24H31N3O3, MW:409.5 g/mol |

Biomarker Validation Framework

Context of Use (COU) in Biomarker Development

Question: Why is defining the "Context of Use" (COU) critical for biomarker validation in clinical research?

Answer: The COU is a concise description of the biomarker's specified purpose, including its category and intended application in drug development or clinical practice [38]. A clearly defined COU is essential because it directly determines the study design, statistical analysis plan, choice of population, and the acceptable performance characteristics of the analytical assay [38]. For example, validating a diagnostic biomarker requires evaluating its accuracy against an accepted clinical standard, while a pharmacodynamic/response biomarker must be tested in patients undergoing the specific treatment to show target engagement [38]. The FDA Biomarker Qualification Program requires a clear COU to begin the submission process [39].

The following diagram outlines the strategic decision-making process for selecting an assay technology based on the biomarker's Context of Use and key performance needs:

Analytical vs. Clinical Validation

It is crucial to distinguish between two key validation stages:

- Analytical Validation: Establishes that the test method itself is reliable and reproducible. It evaluates technical performance characteristics such as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision, and dynamic range [38]. This ensures the assay consistently measures the biomarker accurately.

- Clinical Validation: Evaluates whether the biomarker measurement usefully identifies, measures, or predicts the clinical outcome or biological state for its intended Context of Use [38]. It answers the question: Does the biomarker result correlate with the patient's health, disease, or response to treatment? A robust analytical validation is a prerequisite for a successful clinical validation [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) actually tell me about my biomarker's performance? The AUC is a single metric that summarizes the overall ability of your biomarker to distinguish between diseased and non-diseased individuals across all possible classification thresholds [40]. It represents the probability that a randomly selected diseased individual will have a higher test result than a randomly selected non-diseased individual [41]. AUC values range from 0.5 to 1.0 [40]. The following table provides standard interpretations for AUC values:

| AUC Value | Interpretation | Clinical Usability |

|---|---|---|

| 0.9 - 1.0 | Excellent | Very good diagnostic performance [40] |

| 0.8 - 0.9 | Considerable / Good | Clinically useful [40] |

| 0.7 - 0.8 | Fair | Limited clinical utility [40] |

| 0.6 - 0.7 | Poor | Very limited clinical usability [40] |

| 0.5 - 0.6 | Fail | No better than chance [40] |

2. My biomarker has a statistically significant AUC, but the value is only 0.68. Is it clinically useful? A statistically significant AUC does not automatically imply clinical utility [40]. An AUC of 0.68 falls into the "Poor" interpretation category. While it indicates the biomarker performs better than random chance (AUC=0.5), its discriminatory power is likely too weak for reliable clinical decision-making as a stand-alone test [40]. You should investigate whether the biomarker adds predictive value to existing clinical factors or if its performance can be improved by combining it with other markers.

3. How do I determine the optimal cut-off point for my continuous biomarker? The optimal cut-point is the value that best separates your two groups (e.g., diseased vs. non-diseased) and depends on the clinical context. Several statistical methods can be used, with the Youden index being one of the most common [41]. The Youden index (J) is calculated as J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1 [41]. The threshold that maximizes this value is considered optimal for balancing sensitivity and specificity. Other methods include the Euclidean index and the Product method, which often yield similar results [41].

4. Why are the Positive and Negative Predictive Values (PPV & NPV) for my biomarker different in a new population? Unlike sensitivity and specificity, PPV and NPV are highly dependent on the prevalence of the disease in the target population [42] [43]. If your initial validation was in a high-prevalence setting (e.g., a specialist clinic) and you apply the test to a low-prevalence setting (e.g., general screening), the PPV will decrease and the NPV will increase [43]. You can recalculate them using Bayes' theorem if you know the new prevalence, as well as your test's sensitivity and specificity [43]:

- PPV = (Sensitivity × Prevalence) / [ (Sensitivity × Prevalence) + (1 - Specificity) × (1 - Prevalence) ]

- NPV = (Specificity × (1 - Prevalence)) / [ (1 - Sensitivity) × Prevalence) + (Specificity × (1 - Prevalence)) ]

5. What does it mean to have a "well-calibrated" prediction model, and how is it assessed? A well-calibrated model means that its predicted probabilities of an outcome accurately match the observed frequencies in the data [44]. For example, if the model predicts a 20% risk for a group of patients, approximately 20% of those patients should experience the event. Calibration is often assessed visually using a calibration plot, which plots the predicted probabilities against the observed proportions [44]. A perfectly calibrated model would follow a 45-degree line on this plot. Statistical tests like the Hosmer-Lemeshow test can also be used, but they are sensitive to sample size.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Discriminatory Power (AUC < 0.75)

Problem: Your biomarker's AUC is considered "Fair" or "Poor," limiting its clinical utility [40].

Potential Solutions & Diagnostic Steps:

- Re-evaluate Data Distributions: Check if the distributions of your biomarker in the diseased and non-diseased groups overlap significantly. Non-parametric ROC analysis may be more appropriate than a binormal model if the data is skewed [41].

- Explore Feature Engineering: Investigate if transforming the biomarker (e.g., using a logarithm) or creating a ratio with another clinical variable improves discrimination. For instance, studies have found success with ratios like the Monocyte-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR) or Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII) rather than using cell counts alone [45].

- Consider a Multi-Marker Model: A single biomarker is often a weak stand-alone predictor [46]. Use multivariate analysis or machine learning techniques to build a model that combines your biomarker with other clinical or laboratory variables [44] [47]. For example, a study on young-onset colorectal cancer used a Random Forest model incorporating multiple features to achieve an AUC of 0.888 [47].

- Check Data Quality: Ensure there are no errors in data collection, labeling, or adherence to the gold standard diagnosis.

Issue 2: Selecting an Inappropriate Cut-Off Point

Problem: The chosen cut-point leads to unacceptably low sensitivity or specificity for your clinical application.

Potential Solutions & Diagnostic Steps:

- Define the Clinical Goal:

- Is the test for "Rule-Out"? Prioritize high sensitivity to avoid missing diseased individuals (e.g., for screening). You may choose a cut-point that gives >90% sensitivity.

- Is the test for "Rule-In"? Prioritize high specificity to avoid false positives (e.g., confirming a diagnosis before invasive treatment). You may choose a cut-point that gives >90% specificity.

- Compare Methods: Calculate the optimal cut-point using different methods (Youden Index, Euclidean index, etc.) to see if they converge on a similar value, which increases confidence in its validity [41].

- Validate Clinically: The statistically optimal point may not be clinically optimal. Engage with clinical collaborators to determine the acceptable trade-off between false positives and false negatives. Use the ROC curve to visualize the sensitivity and specificity at different thresholds [42].

Issue 3: Model is Poorly Calibrated

Problem: Your risk prediction model's estimated probabilities do not match the observed outcomes (e.g., it systematically over- or under-predicts risk).

Potential Solutions & Diagnostic Steps:

- Inspect the Calibration Plot: This is the first step. The plot will show you if the miscalibration is consistent across all risk levels or only in certain ranges [44].

- Apply Recalibration Techniques:

- Platt Scaling: This method uses logistic regression to transform the output of a model into a probability distribution over classes.

- Isotonic Regression: A more powerful non-parametric method that can learn a non-linear transformation, useful for complex miscalibration patterns.

- Use Bayesian Methods: Incorporate prior knowledge about the expected outcome rates to adjust the model's probabilities, which can be particularly helpful with small datasets.

Experimental Protocols for Key Metrics

Protocol 1: Conducting ROC Curve Analysis

Objective: To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of a novel inflammatory biomarker.

Materials:

- Dataset with continuous biomarker measurements and a confirmed diagnosis (gold standard) for all subjects.

- Statistical software (e.g., R, SPSS, MedCalc).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Ensure your data is clean, with confirmed diseased and non-diseased groups based on a gold standard reference [42].

- Software Command: Run the ROC curve analysis procedure in your chosen software. The algorithm will calculate sensitivity and 1-specificity for every observed value of your biomarker [42].

- Output Generation:

- The ROC Curve: A plot of sensitivity (TPR) vs. 1-specificity (FPR) [48] [49].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): The primary measure of discriminatory power, including its 95% confidence interval [40] [42].

- Coordinates of the Curve: A table listing all possible thresholds with their corresponding sensitivity and specificity.

Analysis:

- Report the AUC and its 95% CI. An AUC with a narrow confidence interval indicates a more reliable estimate [40].

- Identify the optimal cut-point using the Youden Index [41].

- Report the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV at the chosen cut-point [40].

Protocol 2: Assessing Model Calibration

Objective: To determine whether the predicted probabilities from a risk stratification model are accurate.

Materials:

- Dataset with model-predicted probabilities and observed binary outcomes.

- Statistical software with calibration plotting capabilities.

Methodology:

- Create Groups: Sort your dataset by the predicted risk and divide it into groups (typically deciles) [44].

- Calculate Averages: For each group, calculate the average predicted probability and the observed event rate.

- Generate Calibration Plot: Create a scatter plot where the x-axis is the average predicted probability for each group and the y-axis is the observed event rate [44].

- Plot Reference Line: Add a diagonal line from (0,0) to (1,1) representing perfect calibration.

Analysis:

- A well-calibrated model will have points that lie close to the diagonal line.

- Points above the line indicate the model is under-predicting risk.

- Points below the line indicate the model is over-predicting risk.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Biomarker Validation Statistical Workflow

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Prevalence, PPV, and NPV

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key methodological "reagents" — statistical tools and concepts — essential for robust biomarker validation.

| Research "Reagent" | Function & Explanation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| ROC Curve Analysis | Evaluates the discriminatory ability of a biomarker across all possible thresholds [42]. | Used to assess Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII) for ovarian cancer diagnosis (AUC=0.743) [45]. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Provides a single metric for overall diagnostic performance [40]. | An AUC of 0.80 or above is generally considered clinically useful [40]. |

| Youden Index (J) | A statistical method to identify the optimal cut-point that maximizes both sensitivity and specificity [41]. | Formula: J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1. The cut-point maximizing J is selected [41]. |

| Bayes' Theorem for PPV/NPV | Allows calculation of predictive values for a new population when prevalence is known [43]. | Crucial for translating test performance from a case-control study to a general screening population [43]. |

| Calibration Plot | A visual tool to check the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes [44]. | Used in machine learning model validation for neurological deterioration (deviation: 0.116 indicated excellent calibration) [44]. |

| 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Quantifies the uncertainty around an estimated metric, such as the AUC [40] [42]. | A narrow 95% CI for an AUC suggests a more precise and reliable estimate of performance [40]. |

Distinguishing Prognostic from Predictive Biomarkers in Clinical Trial Design

Foundational Definitions and Regulatory Context

What is the fundamental difference between a prognostic and a predictive biomarker?

A prognostic biomarker provides information about the natural course of a disease, indicating the likelihood of a clinical event (such as disease recurrence or progression) regardless of the specific treatment received. In contrast, a predictive biomarker identifies individuals who are more or less likely to experience a particular effect when exposed to a specific medical product or environmental agent [50] [51].

- Prognostic Biomarker Example: The expression of certain inflammatory gene signatures (e.g., IFI27, CD177) in patients with COVID-19 has been investigated for its ability to predict disease progression to severe outcomes like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), independent of the treatments administered [52].

- Predictive Biomarker Example: In advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor expression of PD-L1 is a predictive biomarker, as patients with PD-L1 ≥1% showed a different response and improved overall survival when treated with the immunotherapy nivolumab compared to those with lower expression [53].

Why is it often challenging to distinguish between these biomarker types in early development?

At the time of initiating a clinical trial, there is often uncertainty about a biomarker's precise role. A biomarker may be prognostic, predictive, or both, and this ambiguity must be accounted for in the trial design [50]. Furthermore, prognostic biomarkers are often investigated as candidates for predictive properties for a specific therapy, adding to the initial complexity [50].

How do regulatory agencies view these distinctions?