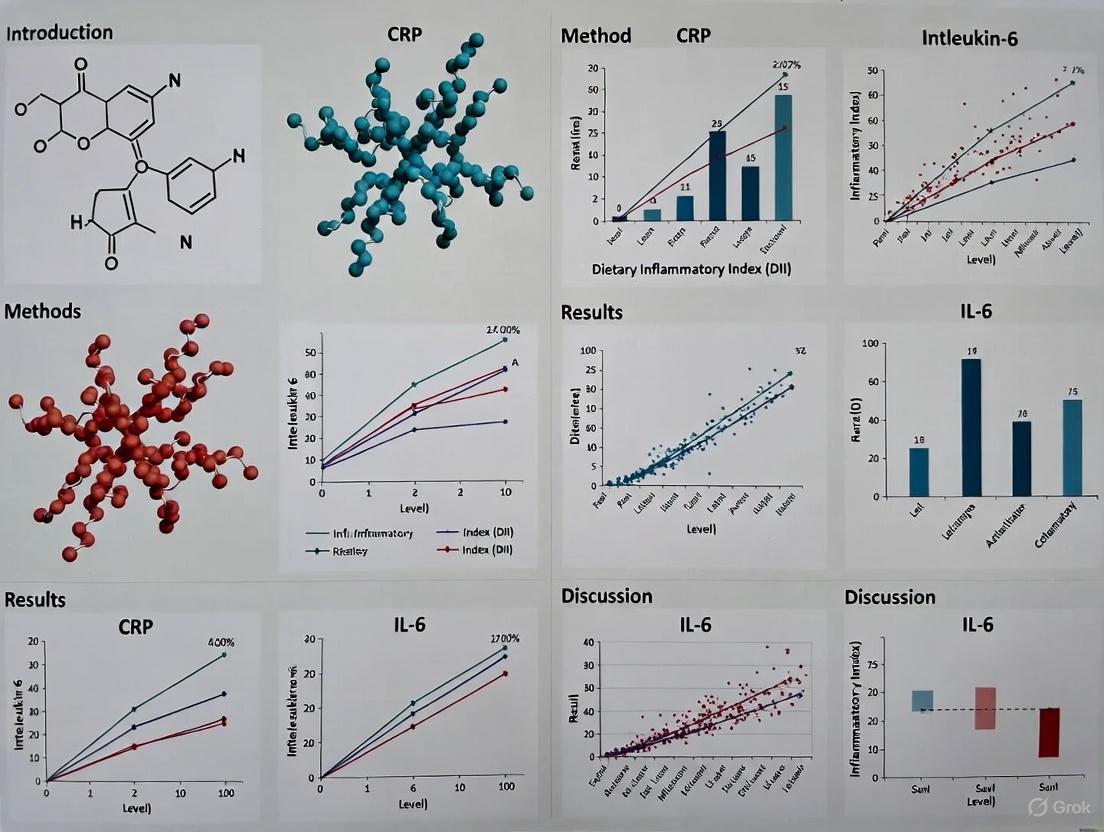

Dietary Inflammatory Index and Inflammatory Biomarkers: Correlations with CRP and IL-6 in Research and Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review examines the evidence linking the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) with key inflammatory biomarkers CRP and IL-6, addressing both methodological considerations and clinical applications.

Dietary Inflammatory Index and Inflammatory Biomarkers: Correlations with CRP and IL-6 in Research and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the evidence linking the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) with key inflammatory biomarkers CRP and IL-6, addressing both methodological considerations and clinical applications. We explore the foundational biology connecting diet to inflammation, methodological approaches for DII implementation across populations, analytical challenges in interpreting biomarker data, and comparative validation of inflammatory indices. Recent studies across diverse clinical contexts—including pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis, PCOS, and malnutrition—demonstrate both consistent patterns and important exceptions in DII-biomarker correlations. For research and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides critical insights for designing robust nutritional interventions, interpreting inflammatory biomarker data, and developing targeted anti-inflammatory therapies that account for dietary influences on inflammatory pathways.

Understanding the Diet-Inflammation Axis: Biological Mechanisms Linking DII to CRP and IL-6

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a well-established subclinical driver of numerous non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, various cancers, and osteoporosis [1] [2] [3]. As a modifiable lifestyle factor, diet plays a critical role in modulating systemic inflammation. However, quantifying the overall inflammatory effect of an individual's entire diet, which contains numerous pro- and anti-inflammatory components, presents a significant challenge. To address this, researchers developed the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) to provide a standardized, quantitative measure for assessing the inflammatory potential of a whole diet [4]. This guide objectively compares the DII's conceptual framework and performance with other emerging dietary inflammatory metrics, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data and methodologies essential for evaluating their application in clinical and population studies.

Conceptual Framework and Development of the DII

The DII is an a priori index, meaning its development was based on pre-existing scientific knowledge rather than derived from a specific dataset. Its primary purpose is to translate complex dietary intake information into a single, interpretable score that reflects the diet's overall inflammatory potential [3] [4].

Foundational Methodology

The development of the DII was a multi-stage process grounded in a systematic review of the literature up to 2010. The foundational methodology can be summarized as follows [4]:

- Literature Review and Parameter Selection: Researchers identified 45 dietary parameters (including nutrients, bioactive compounds, and specific foods) based on peer-reviewed articles that reported associations between these parameters and six established inflammatory biomarkers: IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP.

- Scoring the Inflammatory Effect: For each dietary parameter, a literature-derived "inflammatory effect score" was assigned. This score reflects the consensus from the literature on whether the parameter increases (+1), decreases (-1), or has no effect (0) on the core inflammatory biomarkers.

- Global Intake Database: To standardize individual dietary intake against a global reference, the researchers established a global mean intake and standard deviation for each parameter using dietary data from 11 countries worldwide.

- Individual DII Calculation: An individual's DII is computed by:

- Comparing their reported intake of each parameter to the global mean.

- Converting this comparison into a Z-score and then a percentile to minimize the effect of "right skewing."

- Multiplying the percentile value (centered by doubling and subtracting 1) by the parameter's specific inflammatory effect score.

- Summing the scores across all available parameters to generate the total DII score.

A higher, positive DII score indicates a more pro-inflammatory diet, while a lower, negative score indicates a more anti-inflammatory diet [3] [4].

Conceptual Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual framework and computational workflow for deriving the DII score.

Comparative Analysis of Dietary Inflammatory Indices

While the DII is a widely used tool, other indices have been developed using different methodological approaches. The table below provides a structured comparison of the DII with two other prominent indices: the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP) and the empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI).

Table 1: Comparison of Key Dietary Inflammatory Indices

| Feature | Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP) | Empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Approach | A priori (Literature-based) [3] | A posteriori (Data-driven) [3] | A posteriori (Data-driven) [2] |

| Core Components | 45 nutrients, bioactive compounds, and foods [3] [4] | Food groups [3] | 17 food groups (11 anti-inflammatory, 6 pro-inflammatory) [2] |

| Scoring Method | Sum of weighted, standardized nutrient scores [1] [4] | Weighted sum of food group intake [3] | Summed tertile scores of food group consumption (0, 0.5, 1 point) [2] |

| Interpretation | Higher score = more pro-inflammatory [3] [4] | Higher score = more pro-inflammatory [3] | Higher score = more anti-inflammatory [2] |

| Key Biomarkers in Validation | CRP, IL-6, TNF-α [4] | CRP, IL-6 [3] | hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 [2] |

Performance Comparison with Inflammatory Biomarkers

The ultimate test for these indices is their ability to predict actual levels of systemic inflammation. The following table summarizes key experimental data from recent studies (2025-2026) correlating these indices with inflammatory biomarkers.

Table 2: Association of Dietary Indices with Inflammatory Biomarkers - Recent Experimental Data (2025-2026)

| Index (Study) | Study Population | Key Biomarker Associations | Reported Effect Size / Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DII [5] | 124 adults with obesity (Turkey) | CRP | Significant positive correlation (r=0.258, p=0.004) [5] |

| DII [1] | 3,384 adults with osteopenia/osteoporosis (NHANES) | Depression (PHQ-9) | DII mediated lifestyle-depression link (Effect coef.=0.095-0.115) [1] |

| eADI-17 [2] | 4,432 men (Cohort of Swedish Men) | hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 | Each 4.5-point increase associated with 12%, 6%, 8%, and 9% lower concentrations, respectively [2] |

| EDIP-SP [3] | 501 adults (São Paulo Health Survey) | CRP | Positively associated after adjustment for BMI [3] |

| DII [6] | 4,567 participants (Iranian Cohort) | Monocyte-to-HDL Ratio (MHR) | Pro-inflammatory diet increased MHR by 12.9% in healthy individuals [6] |

| Anti-inflammatory Diet (AnMED) [7] | 468 participants (Spanish Study) | Antihypertensive Use | Each unit increase in DII predicted a 14.28% increase in antihypertensive use [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and critical evaluation, this section outlines the detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the comparison tables.

Objective: To examine the association between lifestyle patterns, DII, and depression in individuals with low bone density. Dietary Assessment: Two 24-hour dietary recall interviews from NHANES (2009-2020). DII Calculation Protocol:

- Intake Standardization: Individual intakes of 27 dietary components (macronutrients, vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, caffeine) were centered by subtracting the global mean intake and divided by the global standard deviation to create Z-scores.

- Percentile Conversion: Z-scores were converted to percentiles to achieve a uniform distribution.

- Centering: Percentiles were doubled and 1 was subtracted to symmetrically distribute the values around 0.

- Inflammatory Weighting: The centered percentiles were multiplied by the respective literature-derived inflammatory effect score for each dietary component.

- Summation: The weighted scores for all components were summed to produce the overall DII score for each participant. Outcome Measurement: Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Mediation analysis tested the role of DII between lifestyle patterns and PHQ-9 scores.

Objective: To develop and validate a user-friendly empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index using multiple inflammatory biomarkers. Study Population: 4,432 men from the Cohort of Swedish Men-Clinical, randomly split into Discovery (n=2,216) and Replication (n=2,216) groups. Dietary Assessment: 145-item Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). Biomarkers: High-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2. Index Development Protocol (Discovery Group):

- Food Grouping: Dietary data were aggregated into food groups.

- Feature Selection: A 10-fold feature selection with filtering based on Lasso regression was used to identify the food groups most correlated with the four inflammatory biomarkers.

- Scoring System: For each of the 17 selected food groups, consumption tertiles were assigned 0, 0.5, or 1 point. Points were summed, with a higher total eADI-17 score indicating a more anti-inflammatory diet. Validation Protocol (Replication Group): The association of the eADI-17 score with inflammatory biomarkers was examined in the Replication group using multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to ensure robustness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and resources required for conducting research on the Dietary Inflammatory Index and related inflammatory pathways.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Dietary Inflammation Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assesses long-term habitual dietary intake for index calculation. | Should be validated for the target population (e.g., 118-item FFQ [6], 145-item FFQ [2]). |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Captures detailed recent dietary intake for precise nutrient calculation. | Often conducted over multiple days (e.g., two non-consecutive days) to account for daily variation [1]. |

| High-Sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) Assay | Quantifies low levels of systemic inflammation. | Immunonephelometric assays on clinical analyzers (e.g., Architect Ci8200) [2]. Commonly used for validation. |

| Cytokine Analysis Kits | Measures specific inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α). | Multiplex immunoassays or ELISA kits. Olink Proteomics panels offer high-sensitivity multiplexing [2]. |

| Global Diet Database | Serves as the reference for standardizing individual intakes in DII calculation. | Contains global mean and standard deviation for 45 dietary parameters from 11 countries [4]. |

| Biobanked Plasma/Serum | Source for biomarker analysis in cohort studies. | Collected after overnight fast, processed (centrifugation), and stored at -80°C until analysis [2] [3]. |

| DII Calculation Algorithm | Software or script to compute DII scores from dietary intake data. | Requires the global database and inflammatory effect scores as inputs for the standardization and weighting process [4]. |

| Pirimicarb | Pirimicarb, CAS:23103-98-2, MF:C11H18N4O2, MW:238.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pirimiphos-methyl | Pirimiphos-methyl Certified Reference Material | Pirimiphos-methyl is a broad-spectrum organophosphate insecticide for research on stored product and agricultural pests. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The Dietary Inflammatory Index provides a standardized, literature-based framework for quantifying the inflammatory potential of diet, distinguishing it from data-driven approaches like the EDIP and eADI. Recent experimental data consistently demonstrates that a higher, more pro-inflammatory DII score is associated with elevated levels of CRP [5], adverse hematological inflammatory markers [6], and worse clinical outcomes, including depression [1] and increased need for antihypertensive medication [7]. While the DII is a robust and widely validated tool, the choice of index depends on the research question, population, and desired balance between biological mechanism (DII) and predictive power in specific cohorts (EDIP, eADI). For researchers in drug development and clinical science, these indices offer valuable tools for integrating dietary inflammation into models of disease risk and progression.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) represent two interconnected pillars of the human inflammatory response. While traditionally employed as clinical biomarkers for monitoring disease activity and systemic inflammation, contemporary research has revealed their direct roles as active contributors to disease pathogenesis across diverse conditions including cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune conditions [8] [9]. This paradigm shift from passive markers to active pathogenic drivers has sparked considerable interest in targeting IL-6 and CRP signaling therapeutically, with recent drug development programs yielding promising results [10]. Understanding the complex biology of these molecules—from their synergistic relationship in the acute phase response to their distinct tissue-level effects—provides critical insights for both diagnostic refinement and therapeutic innovation.

The IL-6-CRP axis exemplifies the intricate connection between immune signaling and end-organ damage. IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine produced by various immune and non-immune cells, serves as the principal hepatic stimulator for CRP production [9]. CRP, in turn, exists in multiple conformational states with distinct biological activities. The conversion from native pentameric CRP (pCRP) to monomeric CRP (mCRP) at sites of inflammation creates a potent pro-inflammatory mediator that drives complement activation, endothelial dysfunction, and vascular pathology [8]. This review examines the expanded biological roles of IL-6 and CRP, their interplay in health and disease, and the experimental approaches driving these discoveries.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The IL-6 Signaling Cascade

IL-6 exerts its biological effects through three distinct signaling modes: classical signaling, trans-signaling, and cluster signaling. Classical signaling involves IL-6 binding to membrane-bound IL-6Rα (CD126) and subsequent dimerization with gp130 (CD130), initiating intracellular JAK/STAT pathway activation. This pathway is limited to cells expressing membrane IL-6R, primarily hepatocytes and certain leukocytes. Trans-signaling, by contrast, occurs when IL-6 binds to soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R), forming a complex that can activate any cell expressing gp130, dramatically expanding the cellular targets of IL-6 and contributing to its pro-inflammatory effects in chronic diseases. Cluster signaling, observed in certain immune cells, involves pre-formed receptor complexes on the cell surface.

The downstream effects of IL-6 receptor activation are primarily mediated through the JAK/STAT pathway, particularly STAT3 phosphorylation, which leads to dimerization and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, STAT3 functions as a transcription factor regulating hundreds of genes involved in inflammation, cell proliferation, and differentiation. Additionally, IL-6 can activate MAPK and PI3K pathways, contributing to its pleiotropic effects on cell survival, apoptosis, and metabolic regulation.

CRP Isoforms and Biological Activities

CRP exists in at least three conformational forms with distinct biochemical properties and biological activities [8] [9]:

- Native pentameric CRP (pCRP): The circulating form primarily synthesized by hepatocytes in response to IL-6 stimulation. pCRP exhibits calcium-dependent binding to phosphocholine on damaged cells and microbial surfaces, activates the classical complement pathway via C1q binding, and serves as the standard form measured in clinical assays.

- Activated pentameric CRP (pCRP): A transitional conformation that occurs when pCRP binds to phosphocholine headgroups exposed on activated cell membranes, particularly under conditions of increased membrane curvature. pCRP exposes neoepitopes not accessible in the native pentamer and exhibits enhanced pro-inflammatory activity.

- Monomeric CRP (mCRP): The tissue-bound form generated through dissociation of pCRP* at sites of inflammation. mCRP exhibits strong pro-inflammatory effects including leukocyte recruitment, platelet activation, and increased endothelial adhesion molecule expression, potentially through interactions with Fcγ receptors and lipid rafts.

Table 1: Biological Characteristics of CRP Isoforms

| Parameter | Pentameric CRP (pCRP) | Monomeric CRP (mCRP) |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Pentameric (115 kDa) | Monomeric (23 kDa) |

| Primary Source | Hepatocytes | Local dissociation of pCRP at inflammatory sites |

| Solubility | Soluble plasma protein | Tissue-insoluble, membrane-associated |

| Detection | Standard clinical assays | Specialized immunoassays |

| Complement Activation | Classical pathway via C1q | Alternative pathway |

| Inflammatory Activity | Moderate | Potent |

The dissociation of pCRP to mCRP represents a crucial amplification step in the inflammatory response. This conformational change occurs preferentially on activated cell membranes, particularly those displaying phosphocholine headgroups due to membrane rearrangement or damage [9]. The resulting mCRP exhibits dramatically different biological activities compared to its pentameric precursor, including enhanced pro-inflammatory effects on endothelial cells, neutrophils, and platelets. This localized conversion mechanism ensures that the potent inflammatory effects of mCRP are largely restricted to sites of tissue injury or inflammation.

The IL-6-CRP Signaling Axis

Figure 1: IL-6 and CRP Signaling Pathway. The diagram illustrates the IL-6 induced JAK-STAT signaling cascade leading to CRP production in hepatocytes, and the subsequent conformational change of pCRP to mCRP at inflammatory sites.

The IL-6-CRP axis represents a fundamental pathway linking immune activation with systemic inflammation. IL-6 stimulation of hepatocytes triggers Janus kinase (JAK) activation, leading to phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Phosphorylated STAT3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to response elements in the CRP gene promoter, driving transcription and translation of pCRP [9]. This well-established connection explains why CRP levels reliably rise following IL-6 induction during inflammation.

Beyond this hepatic production pathway, local tissue factors regulate CRP bioactivity through conformational changes. At sites of inflammation, pCRP binds to phosphocholine groups exposed on damaged cell membranes, triggering a structural transition to pCRP* and subsequent dissociation into mCRP subunits [8] [9]. This localized conversion creates a microenvironment of enhanced inflammatory activity, as mCRP potently activates complement, promotes leukocyte adhesion, and induces cytokine production—effects that are largely absent in the pentameric form.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Longitudinal Clinical Studies

Longitudinal analysis of inflammatory markers provides critical insights into their dynamics during disease progression and recovery. A 2025 study of COVID-19 patients exemplifies this approach, with blood samples collected at multiple timepoints: within 24 hours of admission (t24h), at 48 hours (t48h), at 7 days (t7d), and long-term post-discharge (greater than 1 month, tLongTerm) [11]. This design enabled researchers to characterize the heterogeneous patterns of inflammatory marker elevation and persistence, revealing distinct patient clusters based on their inflammatory profiles.

Serum levels of heparin-binding protein (HBP), serum amyloid A protein (SAA), IL-6, and CRP were measured using a commercial point-of-care device, allowing for rapid clinical assessment [11]. Viral burden was simultaneously assessed through serum viral spike S-protein levels and specific immunoglobulins G, M, and D against SARS-CoV-2 proteins, while tissue injury was evaluated by measuring HMGB-1 levels. This comprehensive approach facilitated correlation between inflammatory markers, viral load, and tissue damage, providing a systems-level view of the inflammatory response.

Key findings from this longitudinal analysis included the persistent elevation of HBP, CRP, and IL-6 beyond one month post-infection, while SAA levels normalized more rapidly [11]. Patients requiring intensive care demonstrated higher initial levels of CRP, IL-6, and HBP, though only IL-6 remained elevated at 48 hours in patients who subsequently expired. Perhaps most importantly, cluster analysis identified four distinct inflammatory phenotypes with different clinical outcomes, underscoring the limitations of single-marker assessments and highlighting the importance of multi-marker profiling for personalized treatment approaches.

Dietary Intervention Assessment

The relationship between dietary patterns and inflammatory markers represents an active area of investigation with significant public health implications. Multiple research groups have developed indices to quantify the inflammatory potential of diet, including the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) and the Empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI) [2] [12]. These tools enable systematic assessment of how dietary components collectively influence systemic inflammation.

The development of eADI exemplifies the rigorous methodology required for creating validated dietary indices. Researchers from the Cohort of Swedish Men-Clinical study analyzed data from 4,432 men with assessment of inflammatory status through four biomarkers: high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1), and tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNF-R2) [2]. Dietary intake was assessed using a 145-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), with participants indicating consumption frequency across eight predefined categories.

The analytical process involved several key stages. First, researchers randomly divided the cohort into Discovery (n=2,216) and Replication (n=2,216) groups. Using the Discovery group, they employed a 10-fold feature selection with filtering based on Lasso regression to identify food groups most strongly correlated with inflammatory biomarkers [2]. From the selected foods, the eADI was constructed based on summed scores of consumption tertiles. Finally, the association of eADI with inflammatory biomarkers was validated in the Replication group using multivariable-adjusted linear regression models, confirming that each 4.5-point increment in eADI-17 score was associated with significantly lower concentrations of all four inflammatory biomarkers.

Table 2: Dietary Assessment Methodologies in Inflammation Research

| Method | Application | Key Components | Inflammatory Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI) | Cross-sectional population studies | 17 food groups (11 anti-inflammatory, 6 pro-inflammatory) | hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | NHANES analysis | 25 nutrients including macronutrients, vitamins, minerals | CRP, IL-6 (literature-derived) |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Cohort of Swedish Men | 145 food items, frequency and portion size | hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 |

| 24-hour Dietary Recall | NHANES DII calculation | Detailed nutrient intake assessment | CRP (correlated with stroke risk) |

This methodology represents a significant advancement over earlier approaches that relied on single inflammatory biomarkers. The incorporation of multiple markers reflecting different aspects of immune activation provides a more comprehensive assessment of diet's impact on inflammatory status. The resulting eADI-17 includes 17 food groups (11 with anti-inflammatory potential and 6 with pro-inflammatory potential), creating a practical tool for clinical assessment and personalized nutrition recommendations [2].

Similar approaches have demonstrated the clinical relevance of dietary inflammation. A 2025 analysis of NHANES data involving 9,914 diabetic patients found that those in the highest DII quartile had a 78% increased risk of stroke compared to those in the lowest quartile, with each unit increase in DII associated with a 13% increase in stroke risk [12]. This association remained significant after adjustment for multiple confounders and exhibited a linear dose-response relationship, highlighting the clinical significance of diet-induced inflammation.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations

The involvement of IL-6 and CRP in neuropsychiatric disorders represents an emerging frontier in psychoneuroimmunology. A 2025 cross-sectional study systematically examined associations between elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, CRP, TNF-α) and neuropsychiatric symptoms of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) [13]. Participants were assessed approximately 6 months after acute infection using standardized neuropsychiatric assessments including the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21), PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), and cognitive testing.

The findings revealed significant associations between elevated inflammatory markers and specific neuropsychiatric manifestations. Elevated IL-6 was associated with greater fatigue severity and reduced motivation, while elevated CRP correlated with subjective cognitive complaints ("brain fog") and objective neuropsychological impairment [13]. These associations remained significant after controlling for potential confounders including age, sex, body mass index, and acute COVID-19 severity, suggesting a potential direct role for inflammation in these symptoms.

Notably, the study implemented rigorous biomarker assessment protocols. Blood samples were collected following an overnight fast and processed using standardized methods. CRP was measured using immunoturbidometric methods, while IL-6 and TNF-α were assessed using multiplex immunoassays [13]. This methodological rigor strengthens the validity of the observed associations and supports the potential utility of these biomarkers for stratifying PASC patients based on inflammatory profiles.

Beyond PASC, the relationship between inflammation and depression has been extensively documented. A study of 4,567 participants found distinct relationships between dietary inflammatory index and hematological inflammatory markers in healthy versus depressed individuals [6]. In healthy individuals, a pro-inflammatory diet was associated with altered monocyte-to-HDL ratio (MHR) and lymphocyte-to-HDL ratio (LHR), while these relationships were absent in depressed individuals, suggesting possible inflammatory pathway dysregulation in major depressive disorder.

Therapeutic Targeting of IL-6 and CRP

The recognition of IL-6 and CRP as active mediators of disease pathology has stimulated significant interest in their therapeutic targeting. Recent clinical developments highlight the translation of this biological understanding into clinical practice. In 2025, Novartis acquired an IL-6 targeted antibody (pacibekitug) for $1.4 billion, reflecting the substantial commercial and therapeutic potential of IL-6 pathway inhibition [10]. This fully human IgG2 monoclonal antibody binds IL-6, preventing interaction with its receptor and subsequent pro-inflammatory signaling.

The therapeutic rationale for IL-6 inhibition is particularly strong in cardiovascular disease, where chronic inflammation drives atherosclerotic progression. Pacibekitug offers potential advantages over existing anti-inflammatory therapies, including quarterly dosing convenience compared to monthly regimens required for alternative IL-6 targeting agents [10]. Phase 3 trials will determine whether this approach provides clinical benefit beyond conventional lipid-targeting therapies, potentially establishing inflammation modulation as a standard component of cardiovascular risk reduction.

CRP represents another attractive therapeutic target, though its direct inhibition has proven more challenging. Alternative strategies include targeting the conformational changes that generate pro-inflammatory mCRP or developing small molecules that interfere with CRP binding to its ligands [8] [9]. The elucidation of the structural basis for pCRP dissociation to mCRP has identified potential intervention points to block this amplification step in the inflammatory cascade without completely eliminating CRP's beneficial functions in host defense.

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for IL-6 and CRP Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP Isoform-Specific Antibodies | Anti-pCRP-8D8 (native pentamer), Anti-mCRP/pCRP* 9C9 and 3H12 (dissociated forms) [9] | Discrimination of CRP conformational states in tissue and plasma | Different fixation methods may affect epitope preservation |

| Multiplex Immunoassay Platforms | Olink Proteomics (NPX quantification), Luminex xMAP technology | Simultaneous measurement of multiple inflammatory biomarkers (IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2) | Normalized Protein Expression (NPX) values follow log2-scale interpretation |

| High-Sensitivity CRP Assays | Immunoturbidometric methods (Architect Ci8200 analyzer) [2] | Quantification of low-grade inflammation in cardiometabolic studies | Standardized fasting blood collection protocols required |

| IL-6 Pathway Modulators | Tocilizumab (IL-6R antagonist), Pacibekitug (IL-6 antibody) [10] | Experimental validation of IL-6-dependent mechanisms | Differential effects on classical vs. trans-signaling |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ), 24-hour dietary recall | Calculation of Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | Multiple assessment days improve accuracy of usual intake estimation |

The investigation of IL-6 and CRP biology requires specialized research tools that continue to evolve in sophistication. Isoform-specific antibodies have been particularly instrumental in advancing understanding of CRP biology, enabling researchers to distinguish between the different conformational states that exhibit distinct biological activities [9]. The anti-pCRP-8D8 antibody specifically recognizes the circulating pentamer, while antibodies such as 9C9 and 3H12 detect neoepitopes exposed in the dissociated pCRP* and mCRP forms, facilitating investigation of CRP dissociation in pathological conditions.

Advanced immunoassay platforms provide the sensitivity and multiplexing capability necessary for comprehensive inflammatory profiling. The Olink Proteomics platform, utilized in the Cohort of Swedish Men study, offers simultaneous measurement of multiple inflammatory biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity, using normalized protein expression (NPX) values that allow relative quantification across samples [2]. These technological advances have enabled large-scale epidemiological studies examining the relationship between numerous environmental factors, including diet, and inflammatory status.

Therapeutic agents targeting the IL-6 pathway serve dual purposes as both clinical treatments and research tools. IL-6 receptor antagonists like tocilizumab have been used to validate the functional significance of IL-6 signaling in various disease models, while the development of direct IL-6 antibodies such as pacibekitug provides additional tools for dissecting the specific contributions of IL-6 to disease pathogenesis [10]. These biological tools continue to refine our understanding of the complex roles played by IL-6 and CRP in health and disease.

The biological roles of IL-6 and CRP extend far beyond their traditional status as non-specific inflammatory markers. Rather, they function as integrated components of a sophisticated inflammatory network with specific effects on disease pathogenesis across multiple organ systems. The IL-6-CRP axis represents a particularly important pathway, with IL-6 serving as the primary inducer of hepatic CRP production, and CRP undergoing tissue-specific conformational changes that locally amplify inflammatory responses.

Contemporary research approaches have been essential in elucidating these complex relationships. Longitudinal studies with multi-marker assessment, dietary intervention studies utilizing validated inflammatory indices, and sophisticated assays capable of discriminating between CRP isoforms have collectively advanced our understanding of inflammatory biology. These methodological advances have revealed the heterogeneous nature of inflammatory responses and the potential for personalized approaches to inflammation modulation.

The therapeutic targeting of IL-6 and CRP pathways represents a promising frontier in the management of inflammatory diseases. The significant investment in IL-6 targeted therapies reflects growing recognition of the clinical importance of this pathway, while ongoing research into CRP modulation may yield novel approaches to controlling inflammation-driven tissue damage. As our understanding of these molecules continues to evolve, so too will our ability to harness this knowledge for improved patient outcomes across a spectrum of inflammatory conditions.

Systemic low-grade inflammation is a key pathophysiological process in the development of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and various cancers [3] [14]. Dietary patterns represent a modifiable factor that significantly influences inflammatory status through multiple biochemical pathways. Understanding the specific mechanisms through which nutrition modulates inflammation is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to develop targeted therapeutic interventions.

The inflammatory response involves a complex cascade of mediators, including acute-phase proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [15] [16]. These biomarkers serve as critical indicators of inflammatory status and are increasingly used to evaluate the efficacy of nutritional interventions. This review synthesizes current evidence on nutritional modulation of inflammatory pathways, with particular focus on the correlation between dietary inflammatory indices and specific biomarkers including CRP and IL-6.

Key Inflammatory Biomarkers and Their Clinical Significance

Inflammation monitoring in clinical research relies on specific biomarkers that reflect systemic inflammatory status. C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-phase protein produced by the liver in response to inflammation, serves as one of the most widely used clinical biomarkers. Interleukin-6 (IL-6), a pro-inflammatory cytokine released in response to various stressors, stimulates hepatic production of CRP and peaks within 90-120 minutes after an inflammatory trigger [15]. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) represents another key cytokine in the inflammatory cascade.

The clinical significance of these biomarkers is substantial. Research demonstrates that IL-6 has superior prognostic value compared to CRP in certain clinical contexts. A secondary analysis of the EFFORT trial found that medical inpatients with high IL-6 levels (≥11.2 pg/mL) had a more than 3-fold increase in 30-day mortality compared to those with lower levels (adjusted HR 3.5, 95% CI 1.95-6.28, p < 0.001) [15]. Furthermore, patients with elevated inflammation showed diminished response to nutritional interventions, suggesting that inflammatory status may predict therapeutic efficacy.

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Biomarkers in Nutritional Research

| Biomarker | Biological Function | Peak Concentration | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | Acute-phase protein produced by liver | 1-2 days after trigger | Most reliable clinical assay for CVD risk assessment; endorsed by CDC/AHA [14] |

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | 90-120 minutes after trigger | Strong predictor of 30-day mortality (adjusted HR 3.5 for high levels); impacts nutritional therapy efficacy [15] |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Within 2 hours | Associated with cartilage breakdown in osteoarthritis; reduced by probiotic/synbiotic interventions [17] [18] |

Dietary Assessment Methods for Inflammatory Potential

Several validated indices have been developed to quantify the inflammatory potential of diets, each with distinct methodological approaches and applications in research settings.

Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)

The DII is an a priori index derived from peer-reviewed research publications assessing associations between dietary factors and inflammatory biomarkers. Comprising 45 dietary parameters including nutrients, bioactive compounds, and foods, the DII generates a continuous score where higher values indicate pro-inflammatory dietary patterns [3]. The computation involves calculating z-scores for consumed nutrients based on mean daily intakes and standard deviations from global nutritional datasets, transforming these to percentile scores, and multiplying by inflammatory effect scores for each parameter [5].

Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP)

The EDIP represents an a posteriori, data-driven index derived using reduced rank regression in cohort studies. An adaptation for the São Paulo population (EDIP-SP), focusing on high processed meat intake and low consumption of fruits, vegetables, rice, and beans, has demonstrated positive associations with plasma CRP concentrations [3]. In comparative studies, EDIP-SP showed more consistent associations with inflammatory biomarkers than other indices, explaining a higher percentage of variance in CRP levels [19] [3].

Empirical Anti-Inflammatory Diet Index (eADI)

Recently developed through a cross-sectional study of 4,432 men, the eADI-17 incorporates 17 food groups (11 anti-inflammatory and 6 pro-inflammatory) selected based on correlations with multiple inflammatory biomarkers including hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, and TNF-R2 [20]. Each 4.5-point increment in eADI-17 (2 SD) was associated with concentrations that were 12% lower for hsCRP, 6% lower for IL-6, 8% lower for TNF-R1, and 9% lower for TNF-R2, demonstrating robust predictive validity for low-grade chronic inflammation [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Dietary Inflammatory Assessment Indices

| Index | Development Approach | Components | Key Associations with Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| DII | A priori literature-based | 45 dietary parameters | Associated with CRP in men; effect modification by sex observed [3] |

| EDIP | A posteriori data-driven | Food groups from reduced rank regression | Positively associated with plasma CRP; explains higher variance in CRP than other indices [19] [3] |

| eADI-17 | Empirical with multiple biomarkers | 17 food groups (11 anti-inflammatory, 6 pro-inflammatory) | Each 4.5-point increase associated with 12% lower hsCRP, 6% lower IL-6 [20] |

| GDQS | Food-based diet quality | Healthy and unhealthy food groups | Healthy submetric inversely associated with CRP; unhealthy submetric positively associated with CRP [3] |

Experimental Evidence for Nutritional Interventions

Anti-Inflammatory Diets and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that anti-inflammatory dietary patterns (Mediterranean, DASH, Nordic, Ketogenic, and Vegetarian diets) significantly reduced cardiovascular risk factors compared to omnivorous diets [14]. Specifically, these interventions were associated with reductions in systolic blood pressure (MD: -3.99, 95% CI: -6.01 to -1.97; p = 0.0001), diastolic blood pressure (MD: -1.81, 95% CI: -2.73 to -0.88; p = 0.0001), LDL cholesterol (SMD: -0.23, 95% CI: -0.39 to -0.07; p = 0.004), total cholesterol (SMD: -0.31, 95% CI: -0.43 to -0.18; p < 0.00001), and hs-CRP (SMD: -0.16, 95% CI: -0.31 to -0.00; p = 0.04) [14].

The Mediterranean diet, characterized by high consumption of extra-virgin olive oil (≥60 mL/day), fatty fish (≥2 servings/week), and polyphenol-rich plant foods, appears to suppress the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, thereby diminishing secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-6 [14]. The ketogenic diet, operating through strict carbohydrate restriction (≤50 g/day) and high fat intake (70-80% of calories), exerts anti-inflammatory effects primarily through β-hydroxybutyrate-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome suppression [14].

Probiotic and Synbiotic Supplementation

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials including 1,321 individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes demonstrated that probiotic and synbiotic supplementation significantly reduced inflammatory markers [17]. The pooled analysis showed weighted mean differences of -0.46 mg/L (95% CI: [-0.77, -0.15], p=0.003) for CRP, -0.43 pg/ml (95% CI: [-0.76, -0.09], p=0.012) for IL-6, and -1.42 pg/ml (95% CI: [-2.15, -0.69], p<0.001) for TNF-α [17].

Subgroup analyses revealed that CRP reduction was most pronounced among participants with baseline CRP ≥3 mg/L, those undergoing longer interventions (≥12 weeks), individuals with T2DM, overweight participants, and when probiotics were administered [17]. IL-6 levels were significantly reduced in obese individuals, particularly with longer treatment durations and synbiotic interventions, while TNF-α reductions were most pronounced in long-term interventions (≥12 weeks), especially among T2DM patients with normal BMI and when probiotics were used [17].

Specific Nutrient Interventions

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly those found in fish, exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties through modulation of eicosanoid and resolvin production [14]. These fatty acids influence inflammatory pathways via multiple mechanisms, including incorporation into cell membranes, alteration of lipid mediator profiles, and regulation of gene expression through nuclear receptors.

Glutamine, considered a conditionally essential amino acid during metabolic stress, attenuates inflammatory response via effects on heat shock protein, nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway, and attenuation of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-18 expression following sepsis [16]. Studies in severe burn patients demonstrate that glutamine supplementation can reduce resting energy expenditure and catecholamine blood levels [16].

Methodological Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: Assessing Dietary Inflammatory Potential

The cross-sectional study by Ferreira et al. provides a robust methodological framework for investigating diet-inflammatory relationships [19] [3]. The study involved 501 participants from the 2015 Health Survey of São Paulo, with dietary data assessed through two non-consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls. Dietary indices (DII, EDIP-SP, and GDQS) were scored based on these recalls, and plasma concentrations of high-sensitive CRP, TNF-α, and adiponectin were determined. Multivariable-adjusted linear regression models examined associations between dietary indices and inflammatory biomarkers, with model fit compared using the coefficient of determination and Akaike Information Criterion [19] [3].

Protocol: Probiotic Intervention in Metabolic Disorders

The systematic review and meta-analysis on probiotic and synbiotic supplementation followed comprehensive methodology [17]. Researchers conducted extensive searches of online databases from inception to September 2025 to identify relevant randomized controlled trials. Data extraction included study characteristics, participant demographics, intervention details, and outcomes. The overall effect size was determined using weighted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals through a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using I² statistics, and subgroup analyses were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity [17].

Protocol: Machine Learning Approaches

A recent study integrated machine learning with clinical data from 600 knee osteoarthritis patients to identify key predictors of disease severity and develop personalized dietary strategies [18]. Random Forest models were developed using Python's scikit-learn library to classify patients into high-pain and low-pain groups based on clinical and biochemical parameters. The dataset was split into training (70%) and testing (30%) subsets, with model performance evaluated based on accuracy, precision, recall, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC = 0.93) [18]. This approach identified BMI, CRP, and IL-6 as critical predictors of pain severity.

Signaling Pathways in Nutritional Modulation of Inflammation

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms through which dietary components modulate inflammatory signaling pathways:

Diagram 1: Nutritional Modulation of Inflammatory Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates key mechanisms through which dietary components influence inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB suppression by omega-3 fatty acids and glutamine, NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition by ketone bodies and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and cytokine regulation.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nutritional Inflammation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Sensitivity CRP Immunoassay | Latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay (e.g., Architect Ci8200) | Quantification of low-grade inflammation; endorsed by CDC/AHA for CVD risk assessment [20] [14] |

| Multiplex Cytokine Panels | MSD Multi-Spot Assay System U-PLEX (IL-6, TNF-α) or Olink Proteomics panels | Simultaneous measurement of multiple cytokines; Olink provides normalized protein expression in log2 scale [15] [20] |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | 145-item FFQ with 8 predefined frequency categories | Assessment of habitual dietary intake for calculating DII, EDIP, or eADI scores [20] |

| Dietary Analysis Software | BeBIS 8.2 or equivalent nutrient analysis programs | Conversion of dietary records to nutrient intake data for inflammatory index calculation [5] |

| ELISA Kits | High-sensitivity kits for IL-6, TNF-α, adiponectin | Quantification of specific inflammatory biomarkers in plasma/serum samples [18] |

| Standardized Probiotic Formulations | Defined strains with CFU quantification | Intervention studies on gut-inflammatory axis modulation [17] |

| Pirlimycin | Pirlimycin, CAS:79548-73-5, MF:C17H31ClN2O5S, MW:411.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pirodavir | Pirodavir, CAS:124436-59-5, MF:C21H27N3O3, MW:369.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The nutritional modulation of inflammatory pathways represents a promising approach for preventing and managing chronic diseases. Evidence from clinical studies demonstrates that anti-inflammatory dietary patterns, specific nutrients, and probiotic supplementation can significantly reduce key inflammatory biomarkers including CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α. The differential effects observed based on baseline inflammation status, intervention duration, and individual metabolic profiles highlight the importance of personalized nutritional approaches.

For researchers and drug development professionals, validated dietary indices such as DII, EDIP, and eADI provide valuable tools for quantifying dietary inflammatory potential, while specific biomarkers offer sensitive measures of intervention efficacy. Future research should focus on refining these tools, elucidating precise molecular mechanisms, and developing targeted nutritional interventions for specific population subgroups based on their inflammatory status and genetic predispositions.

The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) was developed as a quantitative tool to assess the inflammatory potential of an individual's overall diet [21] [22]. Unlike approaches that focus on single nutrients or foods, the DII provides a comprehensive scoring system based on extensive literature review connecting 45 dietary parameters to inflammatory biomarkers [21]. Each food parameter receives a specific inflammatory effect score, with positive values indicating pro-inflammatory potential and negative values indicating anti-inflammatory properties [6]. The total DII score represents the cumulative inflammatory potential of the entire diet, with higher scores indicating more pro-inflammatory diets [23].

This review synthesizes epidemiological evidence connecting DII scores to measurable inflammatory biomarkers, particularly C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), across diverse populations and study designs. We examine the methodological approaches for DII assessment, quantitative relationships between DII and inflammatory markers, underlying biological mechanisms, and clinical implications for chronic disease risk.

Methodological Approaches for DII Assessment in Population Studies

DII Calculation and Dietary Assessment Tools

The development of the DII was based on a systematic review of nearly 2,000 research articles published between 1950 and 2010 that investigated relationships between dietary components and inflammatory biomarkers [22] [24]. The original DII incorporates 45 food parameters, including nutrients, bioactive compounds, and spices such as turmeric, ginger, and garlic [21]. Calculation involves comparing an individual's intake of these parameters to a global reference database, converting intakes to percentile scores, and multiplying by the respective inflammatory effect scores [23] [12].

Population studies employ various dietary assessment methods to calculate DII scores:

- 24-Hour Dietary Recalls: Multiple 24-hour recalls (often 2-3) provide detailed short-term intake data [23] [12]

- Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ): Semi-quantitative FFQs assess habitual dietary intake over extended periods (typically 1 year) [2] [25]

- 7-Day Dietary Recalls: Structured instruments capturing weekly consumption patterns [24]

Different assessment methods can influence DII predictive capability. Studies comparing methods found that 24-hour recalls and 7-day recalls showed similar predictive ability for inflammation, while FFQ-derived DII also demonstrated robust associations with inflammatory biomarkers [24].

Inflammatory Biomarker Measurement

Studies validating DII scores typically measure established inflammatory biomarkers using standardized laboratory protocols:

- High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP): Measured using immunonephelometric assays with intra-assay coefficients of variation typically <5% [2]

- IL-6: Assessed using high-sensitivity ELISA or proteomic panels with intra-assay CV <10% [2]

- TNF-α receptors (TNF-R1, TNF-R2): Determined using proteomic platforms providing normalized protein expression values in log2 scale [2]

- Additional markers: Some studies also measure homocysteine, fibrinogen, and hematological inflammatory ratios [25] [6]

Quality control typically excludes participants with CRP >20 mg/L to avoid capturing acute inflammation from infections or other intensive inflammatory processes [2].

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Biomarkers in DII Validation Studies

| Biomarker | Standard Detection Method | Common Cut-points | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| hs-CRP | Latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay | >3 mg/L [25] | Acute phase protein, cardiovascular risk predictor |

| IL-6 | Olink Proteomics panels or ELISA | >1.6 pg/ml [25] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine, stimulates CRP production |

| TNF-R1/TNF-R2 | Olink Proteomics panels | Varies by study | Receptors for TNF-α, inflammatory signaling |

| Homocysteine | Immunoassays | >15 μmol/L [25] | Cardiovascular risk factor, associated with inflammation |

Quantitative Evidence Linking DII to Inflammatory Biomarkers

Cross-Sectional and Cohort Studies

Multiple large-scale epidemiological studies have demonstrated consistent associations between higher DII scores and elevated inflammatory biomarkers:

The Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS) conducted in Worcester, MA, provided early validation for the DII [24]. Among 495-559 healthy participants followed for one year with quarterly dietary and biomarker assessments, each unit increase in DII was associated with 8-10% higher odds of elevated hs-CRP (>3 mg/L), after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and other confounders [24]. This study demonstrated that DII derived from both 24-hour recalls and 7-day dietary recalls significantly predicted inflammatory status.

The Asklepios Study in Belgium (n=2,524) further confirmed these relationships [25]. After multivariable adjustment, each unit increase in DII was associated with 19% higher odds of elevated IL-6 (>1.6 pg/mL) and 56% higher odds of elevated homocysteine (>15 μmol/L). This study highlighted that women generally consumed more anti-inflammatory diets (mean DII: -1.01) than men (mean DII: 0.90) [25].

More recently, the Cohort of Swedish Men - Clinical (n=4,432) developed and validated an empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI) using multiple inflammatory biomarkers [2]. Each 4.5-point increase in eADI (approximately 2 SD) was associated with 12% lower hs-CRP, 6% lower IL-6, 8% lower TNF-R1, and 9% lower TNF-R2 concentrations, demonstrating robust inverse relationships between anti-inflammatory diet scores and inflammatory biomarkers [2].

Meta-Analytic Evidence

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis specifically investigated the association between DII and elevated CRP across 14 studies comprising 59,941 individuals [21]. The pooled analysis demonstrated that individuals in the highest DII category had 39% higher odds of elevated CRP compared to those in the lowest category. Furthermore, each unit increase in DII as a continuous variable was associated with 10% increased odds of elevated CRP [21].

Subgroup analyses revealed stronger associations in studies that used energy-adjusted DII, measured CRP (vs. hs-CRP), and utilized 24-hour recalls for dietary assessment [21]. This comprehensive meta-analysis provides the strongest level of epidemiological evidence connecting pro-inflammatory diets to systemic inflammation.

Table 2: Summary of Meta-Analyses Examining DII-Inflammation Relationships

| Meta-Analysis Focus | Number of Studies | Pooled Sample Size | Main Findings | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DII and elevated CRP [21] | 14 | 59,941 | OR: 1.39 (95% CI: 1.06-1.14) for highest vs. lowest DII; 10% increased odds per unit DII | I² = 0% |

| DII and cognitive impairment [26] | 9 | 266,169 | RR: 1.34 (95% CI: 1.15-1.55) for high DII and cognitive impairment risk | I² = 56% |

| DII and frailty [27] | 15 | 42,130 | OR: 1.47 (95% CI: 1.28-1.69) for frailty; OR: 1.54 (95% CI: 1.34-1.76) for pre-frailty | I² = 56% |

DII and Inflammation-Related Health Outcomes

Cardiovascular Diseases

Large epidemiological studies have linked pro-inflammatory diets to increased cardiovascular disease risk. An analysis of 43,842 participants from NHANES (1999-2018) found that each unit increase in DII was associated with 4.9% higher odds of coronary heart disease after adjusting for multiple confounders [23]. Several metabolic and lipid indicators mediated this relationship, including triglyceride-glucose index, visceral adiposity index, BMI, and HDL cholesterol [23].

Similarly, in patients with diabetes, higher DII scores significantly increased stroke risk. Among 9,914 diabetic patients from NHANES (1999-2020), those in the highest DII quartile had 78% higher stroke risk compared to those in the lowest quartile, with each unit DII increase associated with 13% higher stroke odds [12]. Restricted cubic spline analyses revealed a linear dose-response relationship between DII and stroke risk in this vulnerable population [12].

Other Inflammation-Related Conditions

The pro-inflammatory effects of diet extend to various other health conditions:

- Cognitive Function: A meta-analysis of nine prospective cohort studies (n=266,169) found that higher DII scores increased cognitive impairment risk by 34%, including mild cognitive impairment and dementia [26]

- Frailty Syndrome: In middle-aged and older adults (15 studies, n=42,130), those with highest DII scores had 47% higher frailty odds and 54% higher pre-frailty odds compared to those with lowest DII scores [27]

- Depression: Emerging evidence suggests connections between pro-inflammatory diets and depression, though relationships with hematological inflammatory markers appear more complex [6]

Biological Mechanisms Connecting Diet to Inflammation

Pro-inflammatory diets influence systemic inflammation through multiple biological pathways. The following diagram illustrates key mechanisms through which dietary components modulate inflammatory processes:

The diagram above illustrates how pro-inflammatory diets activate multiple interconnected pathways leading to systemic inflammation. Key mechanisms include NF-κB pathway activation, NLRP3 inflammasome stimulation, oxidative stress generation, and gut barrier dysfunction [27]. These processes collectively increase production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, which in turn stimulate hepatic CRP production and establish chronic low-grade inflammation [21] [25].

Anti-inflammatory diets, rich in fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols, and various vitamins, counteract these processes through multiple mechanisms including inhibition of inflammatory signaling pathways, reduction of oxidative stress, and preservation of intestinal barrier function [2] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for DII and Inflammation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for DII-Inflammation Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Assays | Application in DII Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Tools | 24-hour dietary recall protocols [24] | Collect individual dietary intake data | Multiple recalls improve accuracy |

| Food Frequency Questionnaires [2] [25] | Assess habitual dietary patterns | Validated for specific populations | |

| USDA Food and Nutrient Database [12] | Convert food intake to nutrient data | Standardized nutrient composition | |

| Inflammatory Biomarker Assays | High-sensitivity CRP assays [2] [24] | Measure systemic inflammation | High sensitivity (detection <0.1 mg/L) |

| Multiplex cytokine panels (IL-6, TNF-α) [2] | Simultaneous measurement of multiple cytokines | High-throughput capability | |

| Olink Proteomics platforms [2] | Measure inflammatory proteins | High specificity and sensitivity | |

| Laboratory Equipment | Architect Ci8200 analyzer [2] | Automated hs-CRP measurement | Standardized clinical measurements |

| ELISA systems [25] | Cytokine quantification | Widely accessible technology | |

| -80°C freezers [2] [6] | Sample preservation | Maintain biomarker integrity |

Epidemiological evidence consistently demonstrates that higher DII scores, indicating more pro-inflammatory dietary patterns, are associated with elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers including CRP and IL-6. These relationships are observed across diverse populations and are maintained after adjustment for potential confounders. The association follows a dose-response pattern, with progressively higher DII scores correlating with increased inflammation.

The inflammatory potential of diet, as quantified by the DII, has important implications for chronic disease risk, including cardiovascular diseases, cognitive decline, and frailty syndrome. These findings underscore the importance of dietary patterns in modulating chronic inflammation and suggest that anti-inflammatory dietary approaches may help mitigate inflammation-related disease risk.

Future research should focus on refining DII assessment methods, elucidating molecular mechanisms linking diet to inflammation, and developing targeted anti-inflammatory dietary interventions for specific population subgroups. The consistent epidemiological evidence connecting DII to inflammatory biomarkers provides a strong foundation for incorporating dietary inflammation assessment into both public health strategies and clinical practice.

Measuring Dietary Inflammation: Methodological Approaches and Research Applications

In nutritional epidemiology, the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) has emerged as a valuable tool for quantifying the inflammatory potential of an individual's overall diet. Unlike approaches that focus on single nutrients or foods, the DII provides a comprehensive summary measure based on the synthesis of extensive scientific literature linking dietary components to inflammatory biomarkers [28]. The ability to translate data from standard nutritional assessment tools like Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) into a validated inflammatory score has significant implications for research into chronic diseases, from cardiovascular conditions to cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders [4] [29]. This guide examines the methodological framework for calculating DII scores, compares its performance with alternative indices, and presents experimental data on its validation against established inflammatory markers, particularly C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), providing researchers with practical protocols for implementation.

Core Methodology: Calculating the DII from FFQ Data

Theoretical Foundation and Dietary Components

The DII is derived from an extensive review of peer-reviewed literature published between 1950 and 2010, examining the relationship between dietary factors and specific inflammatory markers [30] [4]. The original DII was based on 45 dietary parameters, including nutrients, bioactive compounds, and spices, each classified according to their effect on established inflammatory biomarkers like CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-10 [31] [32]. Of these parameters, 36 components exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, while 9 components demonstrate pro-inflammatory effects [31]. In practice, however, the number of components used in calculation often depends on the availability of dietary data in the FFQ being utilized [32] [29].

Step-by-Step Computational Algorithm

The transformation of raw FFQ data into a standardized DII score follows a systematic multi-step process [25] [32] [29]:

Step 1: Dietary Intake Assessment - Researchers collect dietary data using a validated FFQ, which records the habitual consumption frequency and portion sizes of food items over a specific period (typically the past year).

Step 2: Linkage to Global Reference Database - Individual intake data for each DII component is compared to a global reference database that provides robust population-based mean intake values and standard deviations for each parameter. This standardized reference framework enables comparative assessments across different populations [29].

Step 3: Z-score Calculation - For each dietary parameter, a Z-score is computed using the formula: ( Z = \frac{\text{individual mean intake} - \text{global mean intake}}{\text{global standard deviation}} ). This represents the individual's exposure relative to the standard global mean.

Step 4: Centering to Percentile Score - To minimize the effect of right-skewing common in dietary data, the Z-score is converted to a centered percentile score. The cumulative distribution function value is doubled and subtracted by 1 to achieve a symmetric distribution centered around zero.

Step 5: Application of Inflammatory Effect Scores - Each centered percentile score is multiplied by the respective food parameter's "inflammatory effect score" (derived from the literature review), which indicates the strength and direction (pro- or anti-inflammatory) of its relationship with inflammatory biomarkers.

Step 6: Energy Adjustment (for E-DII) - To account for variations in total energy intake, the Energy-adjusted DII (E-DII) can be calculated using the energy density method (dietary intake per 1000 calories) [32] [33].

Step 7: Summation for Overall DII - All food parameter-specific DII scores are summed to create the overall DII score for each participant. A higher composite score indicates a more pro-inflammatory diet, while a lower (more negative) score indicates a more anti-inflammatory diet [28].

The following diagram illustrates this sequential computational workflow:

Diagram: DII Computational Workflow from FFQ data to final score

Comparative Analysis of Dietary Inflammatory Indices

Key Dietary Inflammatory Indexes and Their Characteristics

While the DII is widely used, several dietary indexes have been developed to assess the inflammatory potential of diet. A recent scoping review identified 43 food-based indexes categorized into four groups: dietary patterns, dietary guidelines, dietary inflammatory potential, and therapeutic diets [34]. The following table compares three prominent indexes specifically designed to assess dietary inflammatory potential:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Dietary Inflammatory Indexes

| Feature | Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP) | Energy-Adjusted DII (E-DII) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derivation Approach | Literature-derived (a priori) [31] | Data-driven, hypothesis-oriented (a posteriori) [31] | Modified from DII [33] |

| Components Basis | Primarily nutrients (35 of 45 components) [31] | Exclusively food groups (18 components) [31] [34] | Nutrients and foods, adjusted for energy [33] |

| Component Count | 45 total (9 pro-inflammatory, 36 anti-inflammatory) [31] | 18 total (9 pro-inflammatory, 9 anti-inflammatory) [31] | Varies based on available FFQ data [32] |

| Scoring Method | Sum of literature-derived inflammatory effect scores [25] [29] | Weighted sum based on regression coefficients from RRR [31] | Standardized per 1000 calories intake [32] [33] |

| Influence of Supplements | Yes [31] | No [31] | Depends on underlying DII data |

| Key Applications | Chronic disease risk prediction across populations [4] [29] | Predicting plasma inflammatory markers [31] | Research requiring energy intake adjustment [33] |

Predictive Performance Against Inflammatory Biomarkers

Multiple validation studies have tested the ability of these indexes to predict circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers. The following table synthesizes key comparative findings from major studies:

Table 2: Index Performance in Predicting Inflammatory Biomarkers (% Difference Highest vs. Lowest Quintile)

| Inflammatory Index | CRP | IL-6 | TNFαR2 | Adiponectin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDIP (Women) | +60% [31] | +23% [31] | +7% [31] | -21% [31] |

| EDIP (Men) | +38% [31] | +14% [31] | +9% [31] | -16% [31] |

| DII (Women) | +49% [31] | +21% [31] | +4% [31] | -14% [31] |

| DII (Men) | +29% [31] | +24% [31] | +5% [31] | -4% (NS) [31] |

| E-DII (Older Adults) | +12% (OR for elevated CRP) [35] | +11% (OR for elevated IL-6) [35] | Not reported | Not reported |

Note: CRP = C-reactive protein; IL-6 = Interleukin-6; TNFαR2 = Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Receptor 2; NS = Not Significant

A 2017 comparative study in the Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study concluded that while both DII and EDIP assess dietary inflammatory potential, EDIP showed a greater ability to predict concentrations of plasma inflammatory markers, potentially because it was derived specifically based on circulating inflammatory markers [31]. The correlations between the scores were modest (r=0.29 for women, r=0.21 for men), suggesting they capture related but distinct aspects of dietary inflammatory potential [31].

A 2022 cross-sectional comparative analysis in a middle- to older-aged Irish population further found that while higher diet quality (assessed by DASH, MD, DII, and E-DII) was generally associated with lower concentrations of various inflammatory biomarkers including CRP, neutrophils, and IL-6, the DASH score demonstrated the most consistent relationships after correcting for multiple testing [33].

Experimental Validation Protocols and Data

Standardized Biomarker Validation Methodology

To validate the predictive capacity of DII scores, researchers employ rigorous experimental protocols measuring associations with established inflammatory biomarkers:

Blood Collection and Handling: Participants typically fast for 10-12 hours before venous blood samples (e.g., 10mL) are collected in vacutainer tubes under sterile conditions between 8:30-10:30 am [29]. Serum is obtained through rapid centrifugation and stored at -70°C until analysis.

Biomarker Assessment: Key inflammatory markers are quantified using standardized assays:

- CRP: Measured using high-sensitivity immunoturbidimetric assays or biochip array systems [31] [33].

- IL-6: Quantified using ELISA kits or biochip array systems [31] [28].

- Additional markers: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, fibrinogen, and white blood cell counts may also be assessed depending on the study [29] [33].

Quality Control: Laboratories incorporate blinded quality-control samples with pre-established coefficients of variation (e.g., 2.9-12.8% for IL-6, 1.0-9.1% for CRP) randomly interspersed among participant samples, with batch correction to adjust for potential variability [31].

Statistical Analysis: Multivariable-adjusted linear or logistic regression models test associations between DII scores and biomarker concentrations, typically adjusting for age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity, medication use, and total caloric intake [35] [29].

Key Validation Study Findings

The DII has been validated against inflammatory biomarkers across diverse global populations:

Belgian Population (Asklepios Study): Significant positive associations were observed between DII scores and IL-6 (>1.6 pg/ml: OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.04-1.36) and homocysteine (>15 μmol/l: OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.25-1.94) after adjusting for confounders [25].

Japanese Population (JPHC Study): IL-6 concentrations increased across DII quartiles in Japanese men, validating the DII in an Asian population for the first time [28].

Older Scottish Adults (Lothian Birth Cohort): Higher E-DII scores predicted elevated CRP (>3mg/L) at age 70 (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02-1.24) and elevated IL-6 (>1.6pg/ml) at age 73 (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00-1.23) [35].

Iranian GC Study: Each one-unit increase in DII corresponded with significant increases in hs-CRP (β=0.09), TNF-α (β=0.16), IL-6 (β=0.16), and IL-1β (β=0.10), while anti-inflammatory IL-10 decreased (β=-0.11) [29].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for DII Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment | Validated FFQ (168-item or similar) [32] [29], Standardized portion size visuals, Nutritionist IV software or equivalent | Captures habitual dietary intake for DII calculation |

| Global Reference Database | World mean and standard deviation values for 45 food parameters [25] [29] | Provides standardized reference for Z-score calculation |

| Blood Collection | Vacutainer tubes, Centrifuge, -70°C freezer [29] | Obtains and preserves serum/plasma for biomarker analysis |

| Inflammatory Biomarker Assays | High-sensitivity CRP kits, IL-6 ELISA kits, TNF-α assays, Biochip array systems [29] [33] | Quantifies inflammatory markers for validation |

| Statistical Analysis | SAS, SPSS, R with appropriate regression modeling capabilities | Performs multivariable-adjusted association analyses |

| Pironetin | Pironetin | Pironetin is a potent microtubule polymerization inhibitor that covalently binds α-tubulin. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

| Parbendazole | Parbendazole - CAS 14255-87-9 - Research Compound | Parbendazole for research. Study its potential in AML differentiation therapy. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The DII provides a standardized, literature-based method for translating FFQ data into a quantitative measure of dietary inflammatory potential, with validated calculation methodologies that enable consistent application across diverse populations. While alternative indexes like EDIP may demonstrate stronger predictive capacity for certain inflammatory biomarkers, the DII and its energy-adjusted variant (E-DII) offer well-validated approaches for investigating diet-inflammation-disease relationships. The choice of index should be guided by research objectives, population characteristics, and available dietary data. As research continues to refine these tools, they offer powerful approaches for quantifying how dietary patterns modulate chronic inflammation—a fundamental pathway in many age-related diseases.

Empirical DII (EDII) Development and Validation Studies

The Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Index (EDII) represents a significant methodological advancement in nutritional epidemiology, shifting from literature-derived indices to data-driven approaches for quantifying diet's inflammatory potential. Unlike a priori indices based on existing scientific knowledge, empirical indices derive their structure from statistical relationships between food intake and inflammatory biomarkers in specific populations [36]. This approach captures the complex interactions between multiple dietary components and inflammation, potentially offering greater predictive power for disease risk assessment [36] [37].

The development of EDII addresses a critical need in nutritional science: the ability to assess whole-diet inflammatory potential in a standardized, reproducible manner across different populations [36]. Chronic inflammation mediates the development of numerous chronic diseases, and diet represents a modifiable factor that can either exacerbate or mitigate this inflammatory state [36] [4]. By empirically deriving dietary patterns linked to inflammatory biomarkers, researchers can create tools that more accurately reflect how diet influences inflammation pathways in human populations.

Comparative Analysis of Major Empirical Dietary Indices

Table 1: Overview of Major Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Indices

| Index Name | Development Population | Biomarkers Used | Food Groups Included | Key Validation Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original EDII [36] | Nurses' Health Study (NHS), n=5,230 | IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2 | 18 food groups (9 pro-inflammatory, 9 anti-inflammatory) | Comparing extreme quintiles in NHS-II: CRP 1.52x higher (95% CI: 1.18-1.97), P-trend=0.002; Adiponectin 0.88x lower (95% CI: 0.80-0.96) |

| EDIP-A (Asian-adapted) [37] | Multi-Ethnic Cohort (Singapore), n=2,720 | hsCRP, GlycA | 40 predefined food groups (specific pro/anti breakdown not provided) | Significantly associated with hsCRP and IL-6 (p<0.05); 1-unit increase associated with 13% higher MetS odds (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02-1.26) |

| eADI-17 [2] | Cohort of Swedish Men, n=4,432 | hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 | 17 food groups (11 anti-inflammatory, 6 pro-inflammatory) | Each 4.5-point increment associated with: 12% lower hsCRP, 6% lower IL-6, 8% lower TNF-R1, 9% lower TNF-R2 |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Validation Studies

| Index | Population Characteristics | Inflammatory Biomarker Associations | Health Outcome Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDII [36] | NHS-II (women, n=1,002) and HPFS (men, n=2,632) | Significant prediction of IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, adiponectin (all p<0.05) | Not specifically reported in source |

| EDIP-A [37] | Multi-ethnic Asian population (Chinese, Indian, Malay) | Significant association with hsCRP and IL-6 (p<0.05) | Higher incidence of metabolic syndrome (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02-1.26) |

| eADI-17 [2] | Older Swedish men (74±6 years) | Spearman correlations: hsCRP (-0.17), IL-6 (-0.23), TNF-R1 (-0.28), TNF-R2 (-0.26) | Not specifically reported in source |

Methodological Framework for EDII Development

Core Statistical Approach: Reduced Rank Regression

The development of empirical dietary inflammatory indices predominantly utilizes Reduced Rank Regression (RRR), a hybrid statistical method that combines elements of both exploratory and hypothesis-driven approaches [36] [37]. RRR identifies linear functions of predictors (food groups) that maximize explained variation in response variables (inflammatory biomarkers) [36]. This methodology advantageously uses information on response variables to derive dietary patterns, unlike purely exploratory methods like principal components analysis that rely solely on the covariance structure of foods [36].

The RRR process begins with predefined food groups entered as predictors. For example, the original EDII development used 39 food groups [36], while the Asian-adapted EDIP-A utilized 40 food groups [37]. These food groups serve as inputs to identify dietary patterns most predictive of predetermined inflammatory markers. The first factor extracted from RRR represents the dietary pattern that explains the maximum possible variation in the specified inflammatory biomarkers [37].

Food Group Selection and Weighting