LC-MS/MS Analysis of Lipid Peroxidation Products in Inflammation: Biomarkers, Methods, and Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of LC-MS/MS in analyzing lipid peroxidation products as biomarkers of oxidative stress in inflammatory conditions.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Lipid Peroxidation Products in Inflammation: Biomarkers, Methods, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of LC-MS/MS in analyzing lipid peroxidation products as biomarkers of oxidative stress in inflammatory conditions. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we detail the analysis of key biomarkers including isoprostanes, malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, and oxidized sterols across biological matrices. The article provides methodological insights into sample preparation, derivatization strategies, and analytical workflows while addressing troubleshooting for matrix effects and sensitivity challenges. Through comparative validation against traditional methods and examination of clinical correlations in diabetes, neurodegeneration, and occupational health, this resource serves researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust lipid peroxidation analysis in inflammatory disease research.

Lipid Peroxidation in Inflammatory Pathways: From Basic Mechanisms to Disease Biomarkers

Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in Inflammation

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemically reactive molecules formed from incomplete oxygen reduction, serving as central mediators in the progression of inflammatory disorders [1] [2]. Under physiological conditions, ROS function as critical signaling molecules that modulate various biological processes, including inflammatory responses [3]. However, at excessive concentrations, ROS exert toxic effects by directly oxidizing biological macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, further exacerbating inflammatory responses and causing tissue injury [1] [2]. The professional phagocytes, particularly polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), generate substantial ROS at inflammation sites, leading to endothelial dysfunction and tissue damage through oxidation of crucial cellular signaling proteins [1].

The major ROS involved in inflammatory processes include superoxide anion (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), hydroxyl radical (OH•), and hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [1]. Additionally, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as peroxynitrite (ONOOâ») are generated when superoxide rapidly combines with nitric oxide, adding to the pro-inflammatory burden [1]. The interplay between these reactive species and cellular components creates a complex inflammatory microenvironment that can either resolve or perpetuate disease processes.

Analytical Approaches for ROS and Oxidation Biomarkers

LC-MS/MS-Based Detection of Uric Acid Oxidation Metabolites

Uric acid (UA) serves as an essential water-soluble antioxidant in human bodily fluids, reacting with various ROS and RNS to form specific metabolites that can be utilized as biomarkers for oxidative stress in inflammation [4]. The analytical methodology for detecting these metabolites involves sample preparation, chromatographic separation, and mass spectrometric detection, with optimized parameters for each analyte.

Table 1: Uric Acid Metabolites as Specific Markers for Reactive Species

| UA Metabolite | Reactive Species | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Product Ion (m/z) | Significance in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allantoin (AL) | Free radicals (•OH, RO•) | 157 | 114 | Marker of free radical formation; increases immediately after LPS stimulation |

| Oxaluric Acid (OUA) | Singlet oxygen (¹O₂) | 131 | 59 | Specific for ¹O₂ detection; increases 3h post-LPS and persists up to 48h |

| Triuret (TU) | Peroxynitrite (ONOOâ») | 145 | 42 | Indicator of peroxynitrite; detected 1h after LPS, increasing up to 7h |

| CAPD | Hypochlorite (ClOâ») | 183 | 96 | Marker for hypochlorite formation via myeloperoxidase pathway; detected at 4h post-LPS |

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Collect blood samples using heparin as an anticoagulant

- Centrifuge at 2,330 × g for 10 minutes to obtain plasma

- Add double volume of water followed by double volume of methanol to plasma samples

- Shake vigorously and centrifuge at 26,200 × g for 10 minutes to separate insoluble precipitate

- Inject 5 μL of supernatant into LC-MS/MS system

LC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions:

- Column: Develosil C30-UG (5 μm, 2.0 mm × 250 mm)

- Mobile Phase: Aqueous formic acid (pH 3.0)

- Flow Rate: 0.2 mL/min

- Ionization: Electrospray probe with negative ionization at -3.2 kV

- Detection: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

Method Validation Parameters:

- Recovery: 40-110% depending on metabolite

- Coefficients of variation: Within 7%

- Sample stability: Stable at -80°C for at least 4 weeks

- Detection capability: Picomolar levels

Advanced LC-MS/MS Methods for Lipid Peroxidation Products

Lipid peroxidation generates a wide variety of oxidation products that serve as reliable biomarkers for oxidative stress in inflammation research [5] [6]. The analytical challenges include their low abundance, matrix effects, and instability, which can be addressed through recent advancements in LC-MS/MS techniques.

Table 2: Key Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Inflammation Research

| Biomarker Class | Specific Analytes | Analytical Challenges | Recent LC-MS/MS Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Free MDA, protein adducts | High reactivity, artifactual formation | Derivatization approaches, simpler procedures to reduce errors |

| Isoprostanes | F₂-isoprostanes, IsoPGF₂α | Low abundance, complex matrix | Improved sensitivity through advanced ionization techniques |

| Oxidized Sterols | 7-ketocholesterol, cholestan-3β,5α,6β-triol | Complex extraction, ionization efficiency | Matrix effect management, robust extraction protocols |

| 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) | HNE-histidine adducts, Michael adducts | Protein binding, secondary modifications | Specific MRM transitions, enzymatic release from adducts |

Sample Preparation Workflow for Lipid Peroxidation Products:

- Lipid Extraction: Use Folch's solution (chloroform:methanol, 2:1 v/v) for comprehensive lipid extraction

- Saponification: For total malondialdehyde measurement, subject samples to alkaline hydrolysis

- Derivatization: Employ derivatizing agents such as 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine for carbonyl compounds

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Utilize C18 or specialized cartridges for cleanup and preconcentration

- Reconstitution: Redissolve in MS-compatible solvent for injection

LC-MS/MS Instrumental Parameters:

- Analytical Column: C18 reverse-phase column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8-2.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Methanol or acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient Program: Optimized for each biomarker class (typically 5-95% B over 10-20 minutes)

- Ion Source Parameters: ESI voltage: ±3.5-4.5 kV, vaporizer temperature: 300-400°C, sheath gas pressure: 40-60 psi

Experimental Models for Studying ROS in Inflammation

LPS-Induced Pseudo-Inflammation in Human Blood

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of human blood provides a robust ex vivo model for studying the temporal dynamics of ROS formation and oxidative stress during inflammatory responses [4].

Protocol for LPS-Induced Inflammation Model:

- Blood Collection: Draw fresh blood from healthy human volunteers using heparin as an anticoagulant

- Sample Allocation: Divide approximately 20 mL of blood into two aliquots

- LPS Treatment: Add LPS dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline to one aliquot at a final concentration of 2.5 μg/mL

- Incubation: Incubate both treated and control blood samples at 37°C with gentle agitation

- Time-Course Sampling: Remove 500 μL of blood at hourly intervals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 24, 48h)

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge samples at 26,200 × g for 5 minutes and collect supernatant as plasma

- Sample Storage: Freeze plasma immediately at -80°C until analysis

Time-Course of ROS-Specific Metabolite Formation:

- Immediate (0-1h): Allantoin formation indicates free radical generation

- Early Phase (1-4h): Triuret detection signifies peroxynitrite formation

- Middle Phase (3-8h): Oxaluric acid appearance confirms singlet oxygen production

- Late Phase (4-48h): CAPD detection demonstrates hypochlorite generation via myeloperoxidase

Detection of Intracellular Superoxide Anion

Accurate measurement of intracellular superoxide anion (O₂•â») is crucial for understanding its role in oxidative stress during inflammation [7]. The LC/MS-based method using hydroethidine (HE) as a probe provides specific detection of the superoxide-specific product 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-Eâº).

Experimental Protocol for Intracellular Superoxide Detection:

- Cell Culture: Maintain rat cardiovascular epithelial cells (RACEs) in appropriate medium

- Stimulation: Treat cells with menadione (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 mM) to induce superoxide production

- Probe Incubation: Load cells with 50 μM HE for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Cell Lysis: Use RIPA Lysis Buffer for protein extraction

- Protein Precipitation: Add methanol with 3% MS-grade formic acid (1:1 ratio)

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes

- LC-MS Analysis: Inject supernatant and analyze 2-OH-E⺠using LC-MS

LC-MS Conditions for 2-OH-E⺠Detection:

- Column: C18 reverse-phase column

- Mobile Phase: Methanol/water gradient with 0.1% formic acid

- Detection: Positive ion mode with MRM transition 316.1 → 287.1 for 2-OH-Eâº

- Quantification: Use standard curve generated from authentic 2-OH-Eâº

Validation Parameters:

- Proportionality confirmed between Xanthine/XOD-generated O₂•⻠and 2-OH-E⺠formation

- Linear range: 0.01-0.6 mM menadione stimulation

- Specificity: No interference from ethidium (Eâº) due to chromatographic separation

ROS Signaling Pathways in Inflammation

The molecular mechanisms by which ROS mediate inflammatory responses involve complex signaling pathways that regulate cellular responses. The diagram below illustrates key ROS signaling pathways in inflammatory processes.

ROS Signaling in Inflammation Pathways

The signaling pathways illustrate how ROS, particularly Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, function as second messengers in inflammatory processes by oxidizing critical cysteine residues in protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and PTEN, leading to their inactivation [3]. This oxidation results in sustained activation of MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, promoting inflammatory gene expression and cell survival. Concurrently, excessive ROS can trigger lipid peroxidation, leading to ferroptosis - an iron-dependent form of cell death implicated in inflammatory tissue damage [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ROS and Inflammation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Inducers | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Menadione, Xanthine/Xanthine Oxidase | Induce controlled ROS production in experimental models | LPS: 2.5 μg/mL for blood models; Menadione: 0.01-0.6 mM for cellular studies |

| Specific Inhibitors | Apocynin (NOX inhibitor), VAS2870 (NOX inhibitor), Ferrostatin-1 (Ferroptosis inhibitor) | Target specific ROS-generating systems or oxidative death pathways | Ferrostatin-1: 1-10 μM for ferroptosis inhibition; Apocynin: 100-500 μM for NOX inhibition |

| Detection Probes | Hydroethidine (O₂•â»), MitoSOX (mitochondrial O₂•â»), Hâ‚‚DCFDA (general ROS) | Specific detection of different ROS types in cellular systems | Hydroethidine: 50 μM loading for 30 min; Specific detection requires LC-MS separation of 2-OH-E⺠|

| Antioxidant Enzymes | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase, Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) | Scavenge specific ROS; used to confirm ROS involvement in pathways | SOD: Converts O₂•⻠to H₂O₂; Catalase: Degrades H₂O₂ to H₂O and O₂ |

| LC-MS Standards | 2-OH-Ethidium, Allantoin, Triuret, 4-HNE, 8-iso-PGF₂α, MDA derivatives | Quantitative reference standards for accurate biomarker measurement | Critical for method validation and absolute quantification; use stable isotope-labeled analogs for best accuracy |

| Sample Preparation | Methanol with formic acid, RIPA Lysis Buffer, Folch's solution (chloroform:methanol) | Protein precipitation, cell lysis, lipid extraction | Methanol with 3% formic acid: 1:1 sample:precipitant ratio; Folch's solution: 2:1 chloroform:methanol |

| Malabaricone C | Malabaricone C, CAS:63335-25-1, MF:C21H26O5, MW:358.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Malaoxon | Malaoxon|Purity |Research Use Only | Malaoxon is the bioactive oxon metabolite of Malathion, an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Concluding Remarks

The integration of advanced LC-MS/MS methodologies with robust experimental models of inflammation provides powerful approaches for quantifying ROS-mediated oxidative stress in inflammatory processes. The protocols and analytical strategies outlined in this application note enable researchers to accurately measure specific biomarkers of oxidative damage, unravel complex ROS signaling pathways, and evaluate potential therapeutic interventions targeting oxidative stress in inflammatory diseases. The continued refinement of these techniques, particularly through improved sensitivity and specificity of LC-MS/MS platforms, promises to further enhance our understanding of the intricate relationships between ROS, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

Lipid peroxidation is a fundamental redox process wherein oxidants attack lipids containing carbon-carbon double bonds, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cellular membranes [5]. This process generates a diverse array of oxidation products that function as crucial signaling mediators in physiological processes but can also contribute to pathological oxidative damage and inflammation when dysregulated [5] [10]. Within the context of inflammation research, comprehensive profiling of lipid peroxidation products using LC-MS/MS provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions [11] [6]. Lipid peroxidation proceeds through two primary mechanistic routes: non-enzymatic autoxidation driven by free radicals and enzymatic peroxidation catalyzed by specific oxidoreductases [9] [12]. This application note delineates the distinct mechanisms, key products, and advanced analytical strategies for investigating these pathways in inflammatory disease models, providing researchers with detailed protocols for implementing these analyses in drug discovery and development workflows.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Lipid Peroxidation

The Lipid Peroxidation Chain Reaction

The classical chain reaction of lipid peroxidation comprises three distinct phases: initiation, propagation, and termination [9] [5]. In the initiation phase, a reactive oxygen species abstracts a hydrogen atom from a bis-allylic carbon in a PUFA side chain, forming a carbon-centered lipid radical (L•) [9]. During propagation, this radical rapidly reacts with molecular oxygen to form a lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•), which can subsequently abstract a hydrogen atom from an adjacent PUFA, generating a lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) and propagating the chain reaction [9] [5]. The termination phase occurs when radical species interact with each other or with radical-trapping antioxidants such as vitamin E, forming stable non-radical products [9] [5] [12]. The susceptibility of PUFAs to peroxidation increases with the number of bis-allylic positions, making docosahexaenoic acid (22:6) and arachidonic acid (20:4) particularly vulnerable to oxidative attack [9] [13].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Enzymatic versus Non-enzymatic Lipid Peroxidation Pathways

| Characteristic | Non-enzymatic Pathway | Enzymatic Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Initiators | hydroxyl radical (HO•), hydroperoxyl radical (HO₂•), peroxyl radicals [5] | Lipoxygenases (LOX), Cyclooxygenases (COX), Cytochrome P450 (CYP) [9] |

| Iron Dependence | Required (Fenton chemistry) [9] [12] | Iron present in active site of LOX/COX enzymes [9] |

| Site Specificity | Non-specific, targets all available PUFAs [13] | Highly specific regio- and stereoselective oxidation [9] |

| Primary Products | Lipid hydroperoxides with diverse isomeric profiles [13] | Specific hydroperoxide regioisomers (e.g., 5-HETE, 15-HETE) [9] |

| Secondary Products | MDA, 4-HNE, isoprostanes with complex isomeric mixtures [5] [13] | Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, lipoxins, hepoxilins [9] [5] |

| Biological Context | Predominantly pathological oxidative stress [9] [10] | Physiological signaling and regulated inflammation [9] [5] |

| Inhibitors | Radical-trapping antioxidants (Vitamin E) [9] [12] | Enzyme-specific inhibitors (COX inhibitors, LOX inhibitors) [9] |

Non-enzymatic Lipid Peroxidation

The non-enzymatic pathway, also termed non-enzymatic phospholipid autoxidation, is predominantly an iron-dependent process [12]. Within biological systems, redox-active iron (Fe²âº) reacts with hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) via the Fenton reaction to generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (HO•) [9]. These radicals initiate peroxidation by abstracting hydrogen atoms from PUFAs [9] [12]. The resulting carbon-centered radicals (L•) undergo molecular oxygen addition, forming lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•) that propagate the chain reaction [12]. Critically, lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) themselves can participate in Fenton-type reactions, undergoing reductive cleavage by Fe²⺠to generate highly reactive alkoxyl radicals (LO•) that further amplify peroxidation cascades [9]. This autocatalytic propagation continues until termination occurs via radical-radical reactions or antioxidant intervention [12]. Non-enzymatic peroxidation generates complex mixtures of regio- and stereoisomers including bioactive secondary products such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), and isoprostanes [5] [13]. These electrophilic species can form adducts with cellular proteins and DNA, potentially disrupting function and propagating inflammatory signaling [5] [10].

Enzymatic Lipid Peroxidation

Enzymatic lipid peroxidation is catalyzed by three major enzyme families: lipoxygenases (LOX), cyclooxygenases (COX), and cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes [9]. These metalloenzymes catalyze the highly regio- and stereospecific oxidation of PUFAs to produce defined hydroperoxide products that serve as precursors for potent lipid mediators [9] [5]. LOX enzymes insert molecular oxygen specifically at carbon positions 5, 12, or 15 of arachidonic acid, generating corresponding hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs) that are further metabolized to leukotrienes, lipoxins, and hepoxilins [9] [5]. The COX pathway transforms arachidonic acid into prostaglandin endoperoxides that are subsequently converted to various prostaglandins and thromboxanes [9]. The CYP enzymes, particularly those in the CYP4A family, can directly oxidize fatty acids or function as P450 oxidoreductases (POR) that generate Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to support non-enzymatic peroxidation [9]. Unlike the non-specific products of autoxidation, enzymatically-derived oxylipins typically function as potent signaling molecules at nano- to picomolar concentrations, regulating inflammation, vascular tone, and immune responses through specific receptor-mediated pathways [5] [11].

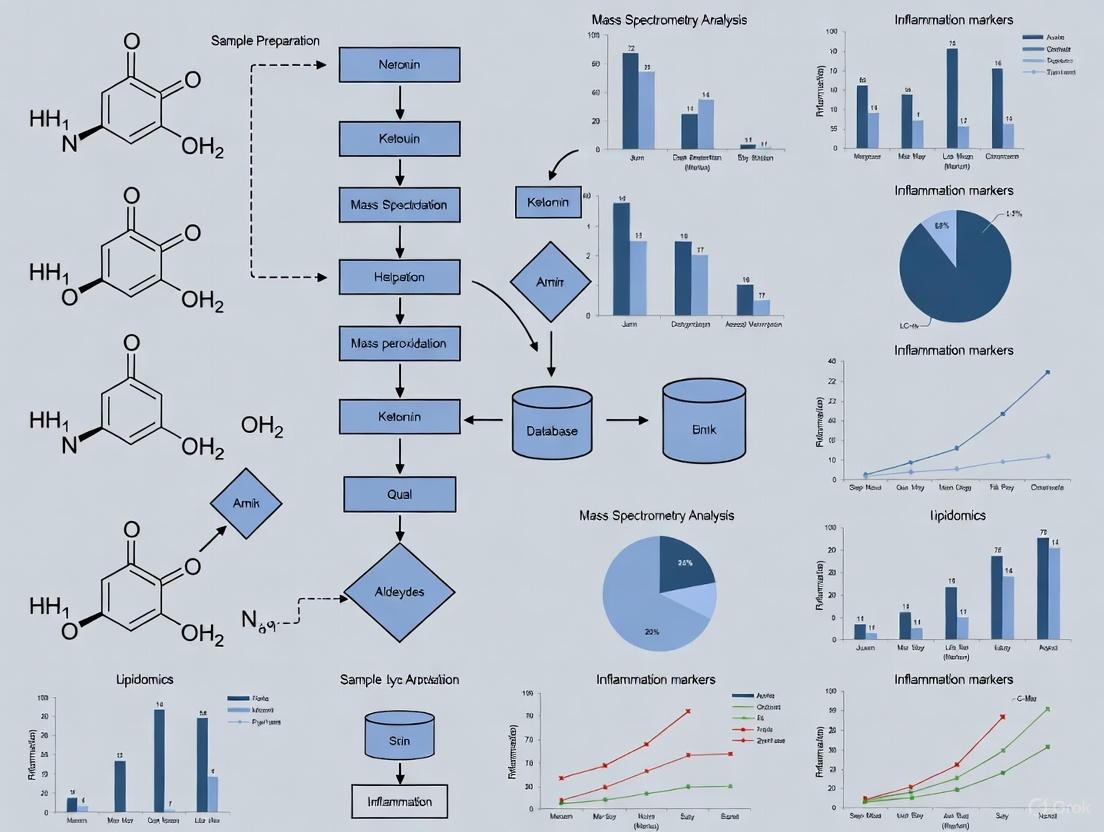

Diagram 1: Integrated Pathways of Lipid Peroxidation. The diagram illustrates both non-enzymatic (yellow) and enzymatic (green) initiation mechanisms, propagation phases, and termination via antioxidants (blue).

Analytical Protocols for LC-MS/MS Analysis of Lipid Peroxidation Products

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Protocol: Solid-Phase Extraction of Oxylipins from Biological Matrices

Principle: This protocol describes a robust method for extracting lipid peroxidation biomarkers from plasma, tissue homogenates, or cell lysates prior to LC-MS/MS analysis, ensuring efficient recovery while minimizing artificial oxidation during sample processing [13] [6].

Reagents:

- Methanol (LC-MS grade)

- Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade)

- Water (LC-MS grade)

- Formic acid (Optima LC-MS grade)

- Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in ethanol (0.1% w/v)

- Isotopically labeled internal standards (dâ‚„-15-HETE, dâ‚„-PGEâ‚‚, d₈-5-HETE, dâ‚„-LTBâ‚„, dâ‚â‚-11(12)-EET)

Equipment:

- C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges (50 mg/1 mL)

- Vacuum manifold for SPE

- Nitrogen evaporator

- Refrigerated centrifuge

- Sonicator

Procedure:

- Sample Stabilization: Add 10 μL of BHT solution (0.1%) and 10 μL of antioxidant mixture (containing 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM glutathione) to 1 mL of plasma or tissue homogenate to prevent ex vivo oxidation [6].

- Internal Standard Addition: Spike 50 μL of working internal standard solution (containing 10 ng of each deuterated oxylipin) into 1 mL of biological sample [6].

- Protein Precipitation: Add 4 mL of ice-cold acetonitrile:methanol (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid to the sample. Vortex vigorously for 1 minute and incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes [6].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant to a clean tube.

- SPE Cartridge Preparation: Condition C18 SPE cartridge with 2 mL methanol followed by 2 mL water containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Sample Loading: Load the supernatant onto the conditioned SPE cartridge at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

- Washing: Wash cartridge with 2 mL of water containing 0.1% formic acid, followed by 2 mL of hexane.

- Elution: Elute oxylipins with 2 mL of methyl formate into a collection tube containing 5 μL of 30% glycerol in methanol to prevent complete evaporation.

- Evaporation: Evaporate the eluent under a gentle stream of nitrogen at room temperature until approximately 50 μL remains.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the sample in 100 μL of methanol:water (1:1, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Quality Control:

- Process quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations in duplicate with each batch.

- Monitor extraction efficiency by comparing peak areas of internal standards across samples.

- Include a method blank to monitor background contamination.

LC-MS/MS Analytical Conditions

Protocol: Targeted Quantification of Oxylipins by Reverse-Phase LC-MS/MS

Principle: This method enables simultaneous quantification of >70 oxylipins derived from enzymatic and non-enzymatic peroxidation pathways using reversed-phase chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [11] [6].

LC Conditions:

- Column: Acquity UPLC BEH C18 (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile:isopropanol (90:10, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 10 μL

- Column Temperature: 50°C

- Gradient Program:

- 0 min: 25% B

- 2 min: 25% B

- 10 min: 80% B

- 15 min: 95% B

- 17 min: 95% B

- 17.5 min: 25% B

- 20 min: 25% B

MS/MS Conditions:

- Instrument: Triple quadrupole mass spectrometer

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray ionization (ESI) negative mode

- Ion Source Temperature: 500°C

- Ion Spray Voltage: -4500 V

- Nebulizer Gas: 50 psi

- Heater Gas: 60 psi

- Curtain Gas: 35 psi

- Collision Gas: Medium (8-10 psi)

- MRM Transitions: Monitor at least two transitions per analyte for confident identification

Table 2: Characteristic MRM Transitions for Key Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers

| Analyte Class | Specific Analyte | Q1 Mass (m/z) | Q3 Mass (m/z) | Collision Energy (V) | Retention Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic COX Products | PGEâ‚‚ | 351.2 | 271.2 | -18 | 8.2 |

| PGDâ‚‚ | 351.2 | 271.2 | -20 | 8.5 | |

| Thromboxane Bâ‚‚ | 369.2 | 169.0 | -22 | 7.9 | |

| Enzymatic LOX Products | 5-HETE | 319.2 | 115.0 | -18 | 13.1 |

| 12-HETE | 319.2 | 179.1 | -16 | 13.5 | |

| 15-HETE | 319.2 | 175.1 | -18 | 13.3 | |

| LTBâ‚„ | 335.2 | 195.1 | -16 | 10.8 | |

| Non-enzymatic Products | 8-iso-PGF₂α | 353.2 | 193.1 | -22 | 9.1 |

| 5-iPF₂α-VI | 353.2 | 113.1 | -25 | 9.4 | |

| 4-HNE | 155.1 | 137.0 | -12 | 6.3 | |

| CYP Products | 14,15-EET | 319.2 | 219.1 | -14 | 12.9 |

| 20-HETE | 319.2 | 245.1 | -16 | 13.7 |

Data Processing and Quantification

Protocol: Validation and Quantification of Oxylipin Profiles

Calibration Standards: Prepare calibration curves using authentic standards spanning 0.01-100 ng/mL in methanol:water (1:1, v/v). Include at least eight concentration points with linear regression weighting of 1/x² [6].

Identification Criteria:

- Match retention time (±0.2 min) to authentic standards

- Monitor two MRM transitions per analyte with ion ratio within ±20% of standard

- Signal-to-noise ratio ≥10:1 for the quantifying transition

Quantification: Use peak area ratios of analytes to their corresponding deuterated internal standards for quantification. For analytes without specific internal standards, use structurally similar analogs (e.g., dâ‚„-15-HETE for other HETEs) [6].

Method Validation:

- Accuracy: 85-115% of nominal values

- Precision: ≤15% relative standard deviation

- Recovery: ≥70% for most analytes

- Matrix Effects: Evaluate by post-extraction addition and normalize using internal standards

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Peroxidation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant Inhibitors | Vitamin E (α-tocopherol), Ferrostatin-1, Liproxstatin-1 | Radical-trapping antioxidants that terminate lipid peroxidation chain reactions; used to investigate ferroptosis and oxidative damage mechanisms [9] [12] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor), Zileuton (5-LOX inhibitor), Baicalein (12/15-LOX inhibitor) | Selective inhibition of enzymatic oxylipin pathways; used to dissect contributions of specific enzymatic routes to inflammatory responses [9] |

| Iron Chelators | Deferoxamine, Deferiprone, 2,2'-Bipyridyl | Chelate redox-active iron to suppress Fenton chemistry and non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation; used to validate iron-dependent peroxidation mechanisms [9] |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | d₄-15-HETE, d₄-PGE₂, d₈-5-HETE, d₄-LTB₄, d₄-4-HNE, d₈-isoP | Isotope-labeled analogs of oxylipins and LPO products; essential for stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS quantification to ensure accuracy and precision [6] |

| Activity Assay Kits | Lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) assay kit, Glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) activity assay, 4-HNE ELISA kit | Colorimetric or fluorometric quantification of specific lipid peroxidation parameters; used for high-throughput screening and validation of MS-based findings [13] |

| Oxidized PL Standards | POVPC, PGPC, PEIPC, KOdiA-PC | Defined oxidized phospholipid species for method development and as reference standards; critical for investigating macrophage activation and inflammatory signaling [13] |

| Malonganenone A | Malonganenone A|Cas 882403-69-2 | Inhibitor | Malonganenone A is a marine alkaloid that selectively inhibits plasmodial Hsp70s for antimalarial research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Manidipine dihydrochloride | Manidipine dihydrochloride, CAS:89226-75-5, MF:C35H40Cl2N4O6, MW:683.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Inflammation Research and Drug Development

The distinct molecular signatures generated by enzymatic versus non-enzymatic peroxidation pathways provide valuable insights for inflammatory disease research and therapeutic development [11] [10]. In neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, elevated levels of non-enzymatic peroxidation products like Fâ‚‚-isoprostanes and 4-HNE in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma correlate with disease progression and oxidative damage severity [11] [14]. Conversely, specific shifts in enzymatic oxylipin patterns, particularly elevated 5-LOX and COX-2 products, are observed in chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory skin disorders, and metabolic syndrome [11] [10]. LC-MS/MS-based oxylipin profiling enables researchers to discriminate between these pathways, facilitating identification of specific molecular targets for therapeutic intervention [11] [6]. This approach is particularly valuable in clinical trials for target engagement assessment, where demonstrating modulation of specific oxylipin pathways provides compelling evidence of pharmacological activity [14]. The integration of lipid peroxidation biomarkers into drug development pipelines supports mechanism-based stratification of patients and rational design of combination therapies targeting multiple nodes in inflammatory networks [10] [14].

Diagram 2: LC-MS/MS Workflow for Oxylipin Analysis. The schematic outlines key steps from sample collection to data interpretation for comprehensive lipid peroxidation product profiling.

Lipid peroxidation is a core molecular pathway in inflammatory processes, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes and lipoproteins [15]. This non-enzymatic reaction generates a diverse array of bioactive oxidation products that serve as reliable biomarkers for quantifying oxidative stress in pathological conditions [15] [16]. Among these products, isoprostanes, malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), and oxidized sterols have emerged as clinically significant indicators that are mechanistically involved in disease pathogenesis rather than being mere bystanders [17] [18] [16]. Their measurement provides critical insights into the intensity of inflammatory processes, with implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring in cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic diseases [17] [15] [18].

The analysis of these biomarkers presents significant analytical challenges due to their low concentrations, structural diversity, and susceptibility to ex vivo oxidation [19]. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has become the gold standard methodology, offering the specificity, sensitivity, and multiplexing capability required for accurate quantification in complex biological matrices [19]. This application note details the biological significance, analytical protocols, and research applications of these key biomarker classes within the framework of inflammation research, with particular emphasis on robust LC-MS/MS methods suitable for preclinical and clinical investigation.

Biomarker Classes: Biological Significance and Analytical Characteristics

Isoprostanes

Biological Significance: Isoprostanes are prostaglandin-like compounds formed primarily through the free radical-mediated peroxidation of arachidonic acid, independent of cyclooxygenase enzymes [17] [20]. These compounds are esterified in membrane phospholipids before being released by phospholipases into circulation [17]. Beyond their utility as biomarkers of oxidative stress, certain isoprostanes exhibit potent biological activities mediated largely through the thromboxane A2 prostanoid (TP) receptor, including vasoconstriction, platelet activation, and amplification of inflammatory responses [17] [20]. F2-isoprostanes, particularly 8-iso-PGF2α, are the most extensively studied due to their stability and have been implicated in cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury [17] [16] [20].

Malondialdehyde (MDA)

Biological Significance: MDA is a low-molecular-weight terminal product formed during the peroxidation of PUFAs containing three or more double bonds [15]. It reacts readily with proteins, DNA, and phospholipids, forming stable adducts such as malondialdehyde–lysine in proteins [15]. These adducts accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques and are implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders [15] [16]. While historically popular due to simple spectrophotometric assays (TBARS), MDA measurement lacks specificity unless determined using chromatographic methods [16].

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE)

Biological Significance: 4-HNE is the most toxic and extensively studied aldehyde product of lipid peroxidation, generated primarily from ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic and linoleic acid [18]. Its high reactivity stems from three functional groups: a carbonyl group, a C=C double bond, and a hydroxyl group, enabling it to form Michael adducts with cysteine, histidine, and lysine residues in proteins [18]. 4-HNE functions as an important signaling molecule, influencing numerous pathways including MAPK, Jnk, p38, PKC, Nrf2, and NF-κB, thereby affecting cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [18] [21]. Elevated 4-HNE levels are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetic complications [18].

Oxidized Sterols

Biological Significance: Oxysterols are oxidized derivatives of cholesterol generated through enzymatic activity or ROS-mediated oxidation [18]. Prominent examples include 7-ketocholesterol, 7β-hydroxycholesterol, and epoxycholesterol, which accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques and promote inflammatory responses, apoptosis, and cytotoxicity [18]. These compounds serve as sensitive indicators of cholesterol oxidation under conditions of oxidative stress and are implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, and age-related diseases [18].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers

| Biomarker Class | Precursor Molecule | Primary Formation Mechanism | Biological Activities | Associated Pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprostanes | Arachidonic acid | Free radical peroxidation | Vasoconstriction, platelet activation, inflammation | CVD, atherosclerosis, asthma, COPD [17] [20] |

| MDA | PUFAs (3+ double bonds) | Peroxidation fragmentation | Protein/DNA adduction, atherogenesis | Atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer [15] [16] |

| 4-HNE | ω-6 PUFAs | Peroxidation fragmentation | Protein adduction, cell signaling, apoptosis | Neurodegeneration, cancer, CVD [18] [21] |

| Oxidized Sterols | Cholesterol | Enzymatic/ROS oxidation | Inflammation, apoptosis, cytotoxicity | Atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration [18] |

Table 2: Analytical Considerations for LC-MS/MS Measurement

| Biomarker | Sample Matrices | Sample Preparation | Key Analytical Challenges | Recommended Internal Standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprostanes | Plasma, urine, tissues | Solid-phase extraction, phospholipase hydrolysis | Low basal levels, ex vivo formation, matrix effects | d4-8-iso-PGF2α, d11-8-iso-PGF2α |

| MDA | Plasma, serum, tissues | Derivatization with DNPH, LLE | Sample storage stability, specificity | d8-MDA, MDA-dinitrophenylhydrazone |

| 4-HNE | Plasma, tissues, cells | Derivatization with DNPH, LLE | Protein binding, chemical instability | d3-4-HNE, 4-HNE-dinitrophenylhydrazone |

| Oxidized Sterols | Plasma, LDL, tissues | LLE, saponification, SPE | Autoxidation during processing, low levels | d7-7-ketocholesterol, d6-7β-hydroxycholesterol |

Signaling Pathways in Inflammation

Lipid peroxidation products function not merely as biomarkers but as active mediators in inflammatory signaling cascades. Understanding these pathways is essential for contextualizing their measurement in disease states.

Figure 1: Signaling Pathways of Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Inflammation

The pathway illustrates how reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) initiate lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), generating the four biomarker classes [15] [18]. These biomarkers activate distinct signaling mechanisms: isoprostanes primarily signal through the TP receptor to promote vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation [17] [20]; MDA and 4-HNE form adducts with cellular proteins, disrupting function and activating stress-responsive transcription factors including NF-κB and Nrf2 [15] [18] [21]; oxidized sterols directly promote inflammatory responses in vascular and immune cells [18]. Collectively, these pathways converge to amplify the inflammatory cascade, creating a positive feedback loop that sustains oxidative stress and tissue damage.

Experimental Protocols for LC-MS/MS Analysis

Sample Preparation Workflow

Proper sample handling is critical to prevent ex vivo oxidation and maintain biomarker integrity throughout analysis.

Figure 2: Sample Preparation and Analysis Workflow

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Analysis of Isoprostanes

Principle: This method quantifies F2-isoprostanes, particularly 8-iso-PGF2α, in biological fluids using solid-phase extraction and LC-MS/MS with stable isotope dilution [19].

Reagents:

- Internal standard: d4-8-iso-PGF2α or d11-8-iso-PGF2α

- Solid-phase extraction cartridges (C18 or mixed-mode)

- Methanol, water, ethyl acetate (HPLC grade)

- Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 0.005%)

- Formic acid

Procedure:

- Add antioxidant solution (BHT/EDTA) to fresh plasma/serum immediately after collection

- Spike with internal standard (0.1-5 ng depending on expected levels)

- Acidify sample to pH 3 with formic acid

- Extract using C18 SPE cartridge: condition with methanol, equilibrate with water, load sample, wash with water, wash with hexane, elute with ethyl acetate

- Evaporate eluent under nitrogen stream

- Reconstitute in 50-100 μL methanol/water (50:50, v/v)

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS Conditions:

- Column: C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-2.0 μm)

- Mobile phase: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 20% B to 95% B over 10 min, hold 2 min

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection volume: 5-20 μL

- Ionization: ESI negative mode

- MRM transitions: 8-iso-PGF2α: 353→193; d4-8-iso-PGF2α: 357→197

Protocol 2: Analysis of MDA and 4-HNE via Derivatization

Principle: MDA and 4-HNE are simultaneously analyzed after derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to form hydrazone derivatives, improving chromatographic behavior and sensitivity [19].

Reagents:

- Derivatization reagent: 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine in acetonitrile

- Internal standards: d8-MDA, d3-4-HNE

- Phosphoric acid (0.5%)

- Acetonitrile, methanol (HPLC grade)

Procedure:

- To 100 μL plasma/serum, add internal standards and 200 μL DNPH solution

- Incubate at 45°C for 60 min with occasional shaking

- Add 100 μL phosphoric acid (0.5%) to stop reaction

- Extract with hexane to remove excess DNPH

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 min

- Collect aqueous layer and analyze by LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS Conditions:

- Column: C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm)

- Mobile phase: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: acetonitrile

- Gradient: 40% B to 95% B over 12 min

- Flow rate: 0.25 mL/min

- Injection volume: 10 μL

- Ionization: ESI negative mode for MDA-DNPH (235→161), ESI positive mode for 4-HNE-DNPH (367→349)

Protocol 3: Analysis of Oxidized Sterols

Principle: Oxidized sterols are extracted from biological samples following saponification to release protein-bound fractions, then analyzed by LC-MS/MS [18] [19].

Reagents:

- Internal standards: d7-7-ketocholesterol, d7-27-hydroxycholesterol

- Potassium hydroxide in methanol (1M)

- n-Hexane, ethyl acetate (HPLC grade)

- BSTFA + TMCS (for derivatization, optional)

Procedure:

- Add antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (0.005%) to plasma/serum immediately

- Spike with internal standard mixture

- Saponify with methanolic KOH at 37°C for 2 hours

- Extract with hexane:ethyl acetate (9:1, v/v)

- Evaporate organic layer under nitrogen

- Reconstitute in methanol or derivatize with BSTFA + TMCS

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS Conditions:

- Column: C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile phase: A: 0.1 mM ammonium acetate; B: methanol:acetonitrile (90:10)

- Gradient: 70% B to 100% B over 15 min

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Ionization: APCI positive mode

- MRM transitions: 7-ketocholesterol: 401→383, 7β-hydroxycholesterol: 401→383, 27-hydroxycholesterol: 403→385

Table 3: Method Validation Parameters for LC-MS/MS Assays

| Validation Parameter | Isoprostanes | MDA | 4-HNE | Oxidized Sterols |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 5-2000 pg/mL | 10-5000 nM | 1-1000 nM | 0.1-500 ng/mL |

| LOD | 1-2 pg/mL | 2-5 nM | 0.2-0.5 nM | 0.05 ng/mL |

| LOQ | 5 pg/mL | 10 nM | 1 nM | 0.1 ng/mL |

| Precision (RSD%) | <10% | <12% | <15% | <12% |

| Accuracy | 90-110% | 85-115% | 80-110% | 85-115% |

| Recovery | 85-95% | 75-90% | 70-85% | 80-95% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Lipid Peroxidation Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | d4-8-iso-PGF2α, d8-MDA, d3-4-HNE, d7-7-ketocholesterol | Quantification by stable isotope dilution | Essential for accurate LC-MS/MS quantification [19] |

| Antioxidant Preservatives | BHT, EDTA, glutathione | Prevent ex vivo lipid peroxidation | Add immediately during sample collection [16] |

| Derivatization Reagents | 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), BSTFA+TMCS | Enhance detection sensitivity and chromatography | DNPH for carbonyl compounds; BSTFA for sterols [19] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | C18, mixed-mode (C18/SAX, C18/SCX) | Sample clean-up and preconcentration | Reduces matrix effects in LC-MS/MS [19] |

| LC Columns | C18 (1.7-2.0 μm, 100-150 × 2.1 mm) | Chromatographic separation | Sub-2μm particles for improved resolution [19] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Triple quadrupole MS with ESI/APCI | Detection and quantification | MRM mode for specificity in complex matrices [19] |

| Mansonone F | Mansonone F, CAS:5090-88-0, MF:C15H12O3, MW:240.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nod-IN-1 | Nod-IN-1, MF:C18H17NO4S, MW:343.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Disease Research and Drug Development

Measurement of lipid peroxidation biomarkers provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses across multiple pathological conditions.

Cardiovascular Disease: Isoprostanes are significantly elevated in atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and hypertension, where they contribute to endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation [17] [16]. Studies demonstrate that 8-iso-PGF2α levels correlate with atherosclerotic burden and may predict cardiovascular complications [17]. In aspirin-treated patients with CVD, isoprostanes may serve as alternative activators of the TP receptor when thromboxane A2 levels are low [17].

Neurodegenerative Disorders: Elevated levels of 4-HNE and neuroprostanes (isoprostane-like compounds derived from docosahexaenoic acid) are prominent features of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [18] [20]. 4-HNE-protein adducts disrupt proteostasis, mitochondrial function, and synaptic integrity, accelerating disease progression [18].

Metabolic Diseases: In diabetes mellitus, increased lipid peroxidation products correlate with endothelial dysfunction and the development of vascular complications [15]. MDA and 4-HNE levels are elevated in diabetic patients and associated with insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction [15] [18].

Drug Development Applications: These biomarkers serve important roles in the BIPEDS classification system (Burden of disease, Investigational, Prognostic, Efficacy of intervention, Diagnostic, and Safety) for osteoarthritis and other chronic diseases [22]. They can identify patient populations most likely to respond to antioxidant or anti-inflammatory therapies and provide early feedback on target engagement [22].

The quantitative analysis of isoprostanes, MDA, 4-HNE, and oxidized sterols provides a comprehensive assessment of lipid peroxidation in inflammatory processes. LC-MS/MS methodologies offer the specificity, sensitivity, and multiplexing capability required for accurate quantification of these biomarkers in complex biological matrices. When implemented with rigorous attention to sample integrity and analytical validation, these methods yield valuable insights into oxidative stress mechanisms across cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, metabolic, and inflammatory diseases. The continued refinement of these analytical approaches will enhance our understanding of disease pathogenesis and facilitate the development of targeted therapies addressing oxidative stress in human pathology.

Lipid Peroxidation in Neuroinflammatory and Cardiovascular Diseases

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) is a fundamental chain reaction involving the oxidative degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes, initiated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) or non-radical species [23] [24]. This process generates a diverse array of highly reactive carbonyl species (RCS) and advanced lipoxidation end-products (ALEs) that covalently modify proteins, nucleic acids, and phospholipids, leading to cellular dysfunction [23]. The central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular system are particularly vulnerable to LPO damage due to their high oxygen consumption, abundance of PUFAs, and relatively limited antioxidant capacity [24] [23]. In neurological tissues, phospholipids are enriched with arachidonic acid (ARA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which are highly susceptible to peroxidation, generating neurotoxic aldehydes including 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), malondialdehyde (MDA), and acrolein [24] [25]. Similarly, in the cardiovascular system, LPO products contribute to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and the development of atherosclerotic plaques through multiple pro-atherogenic mechanisms [23] [26]. Accurate assessment of LPO products using advanced analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides crucial insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions for neuroinflammatory and cardiovascular pathologies [19] [6].

Key Lipid Peroxidation Products and Their Pathological Roles

Major LPO Products and Their Cellular Effects

Table 1: Key Lipid Peroxidation Products in Neuroinflammatory and Cardiovascular Diseases

| LPO Product | Precursor PUFA | Chemical Properties | Primary Pathological Effects | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) | ARA, DHA, other PUFAs | Reactive dialdehyde | Protein/DNA cross-linking, mutagenic, membrane permeability alteration, endoplasmic reticulum stress | Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's [27] [24] |

| 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) | ω-6 PUFAs (ARA) | α,β-unsaturated alkenal with 3 functional groups | Protein adduct formation via Michael addition, disruption of enzyme function, signal transduction modulation, gene expression alteration | Cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, ALS [23] [24] |

| Isoprostanes (IsoPs) | ARA | Prostaglandin-like compounds from non-enzymatic peroxidation | Inflammation, vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation | Atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's, Oxidative stress biomarker [19] [24] |

| Neuroprostanes (NeuroPs) | DHA | IsoP-like from DHA peroxidation | Neuronal inflammation, membrane dysfunction | Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Traumatic Brain Injury [24] |

| Acrolein | ARA, DHA | Unsaturated aldehyde | Rapid protein adduction, severe cytotoxicity, glutathione depletion | Neurodegenerative diseases, Cardiovascular diseases [24] |

Quantitative Assessment of LPO Products in Disease States

Table 2: Lipid Peroxidation Product Alterations in Pathological Conditions

| Disease Context | MDA Changes | 4-HNE Changes | Isoprostane/Neuroprostane Changes | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Elevated in serum of hypertensive patients [27] | Increased in vascular tissues | Not specified | Human subjects study showing increased TNF-α and MDA with decreased antioxidant power [27] |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Increased in brain tissue and bodily fluids [24] | Elevated protein adducts in affected brain regions | F2-IsoPs and NeuroPs elevated in CSF and brain tissue | Post-mortem brain studies, CSF analysis from patients [24] |

| Atherosclerosis | Contributes to LDL modification and foam cell formation [23] [26] | Accumulates in atherosclerotic plaques, modifies proteins | IsoPs associated with plaque progression and instability | Animal models, human plaque analysis [23] [26] |

| Thermally Oxidized Oil Consumption | Increased plasma levels with prolonged feeding [27] | Generated from n-6 PUFA peroxidation | Not specified | Rat studies showing increased inflammatory markers and MDA [27] |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | Not specified | Not specified | Increased PUFAs including ARA in cerebrospinal fluid [25] | CSF analysis from TBI subjects compared to non-TBI controls [25] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The pathophysiology of both neuroinflammatory and cardiovascular diseases involves complex interactions between LPO products and cellular signaling pathways. In neurodegenerative conditions, the high concentration of PUFAs in neuronal membranes creates a susceptible environment for peroxidation cascades. The resulting reactive aldehydes, particularly 4-HNE, form covalent adducts with key proteins involved in neuronal homeostasis, including mitochondrial enzymes, cytoskeletal proteins, and signal transduction molecules [24] [25]. These modifications lead to impaired mitochondrial function, disrupted calcium homeostasis, and ultimately neuronal apoptosis. Additionally, LPO products activate neuroinflammatory responses through microglial activation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, creating a vicious cycle of oxidative stress and inflammation that propounds neurodegeneration [24].

In cardiovascular diseases, LPO products contribute critically to atherogenesis through multiple mechanisms. The oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles by LPO products generates oxidized LDL (oxLDL), which is no longer recognized by the LDL receptor but instead by scavenger receptors on macrophages, leading to foam cell formation [23] [26]. Additionally, LPO products such as 4-HNE and MDA modify proteins in the vascular wall, creating neoantigens that trigger inflammatory immune responses. These reactive aldehydes also directly affect endothelial function by modulating the activity of key signaling molecules including endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, resulting in increased adhesion molecule expression, monocyte recruitment, and vascular inflammation [23] [27].

Figure 1: Lipid Peroxidation Pathway in Disease. This diagram illustrates the molecular cascade of lipid peroxidation from initiation through propagation to the generation of reactive products that drive neuroinflammatory and cardiovascular pathologies. Key intermediates include lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•) that propagate the chain reaction, ultimately yielding toxic aldehydes including MDA and 4-HNE that disrupt cellular function in neurological and cardiovascular tissues. The pathway highlights potential intervention points for antioxidant systems.

Analytical Workflow for LC-MS/MS Analysis of LPO Products

Sample Preparation and Derivatization Protocols

Comprehensive analysis of LPO products from biological matrices requires meticulous sample preparation to stabilize reactive analytes and minimize artificial oxidation. For brain tissue samples, rapid homogenization in ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and 0.1% EDTA is essential to prevent ex vivo oxidation [19] [28]. Plasma or serum samples should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C with antioxidants prior to analysis. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) using hydrophilic-lipophilic balanced (HLB) cartridges effectively isolates LPO products while removing interfering matrix components [23] [28].

Derivatization enhances detection sensitivity and specificity for certain LPO products. For MDA analysis, derivatization with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) or 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) improves chromatographic behavior and enables sensitive detection [19] [6]. For 4-HNE and other aldehydes, pentafluorobenzyl bromide (PFB-BR) derivatization facilitates electron capture negative chemical ionization in GC-MS analyses, while for LC-MS/MS approaches, hydrazine-based derivatization reagents improve ionization efficiency and enable multiplexed analysis using mass-tagged reagents [23] [28].

LC-MS/MS Instrumental Parameters and Method Optimization

Table 3: LC-MS/MS Conditions for Comprehensive LPO Product Analysis

| Analytical Parameter | Recommended Conditions | Alternative Options | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography System | UHPLC with C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm) | HILIC for polar metabolites | Column temperature: 40-50°C for optimal resolution [28] |

| Mobile Phase A | Water with 0.1% formic acid | 5mM ammonium formate | Additive choice affects ionization efficiency and adduct formation [28] |

| Mobile Phase B | Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid | Methanol with 0.1% formic acid | Acetonitrile provides better peak shape for oxidized lipids [28] |

| Gradient Program | 5-95% B over 15-20 min | 20-100% B over 10 min for faster analysis | Equilibration time critical for retention time stability [19] [28] |

| Mass Analyzer | QqQ for targeted analysis, Q-TOF for untargeted | Orbitrap for high resolution | QqQ enables MRM for superior sensitivity and quantification [19] [6] |

| Ionization Mode | ESI negative for acids, aldehydes | ESI positive for neutral lipids | Polarity switching may be needed for comprehensive profiling [28] |

| Collision Energies | Optimized for each analyte class | Stepped CE for unknown screening | 15-35 eV typical for oxidized lipids [28] |

Identification and Quantification Strategies

Accurate annotation of LPO products requires multiple layers of evidence including retention time matching with authentic standards when available, accurate mass measurement (typically < 5 ppm error), interpretation of MS/MS fragmentation patterns, and correlation with reference databases [28]. For oxidized complex lipids, fragmentation rules have been established that enable determination of modification type and position along the acyl chain. For example, HCD fragmentation of oxidized phosphatidylcholines produces head group-specific ions (m/z 168.0431 and 224.0695 in negative mode), fatty acyl chain fragments, and modification-specific fragments that localize the oxidation site [28].

Quantification typically employs stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) for each class of LPO products to correct for matrix effects and recovery variations. When SIL-IS are unavailable, structural analogues or deuterated compounds can be used as surrogates [19] [6]. For untargeted analysis, relative quantification based on peak area normalization to internal standards and sample protein content provides semi-quantitative data suitable for biomarker discovery [28].

Figure 2: LC-MS/MS Workflow for LPO Product Analysis. This diagram outlines the comprehensive analytical pipeline for identifying and quantifying lipid peroxidation products from biological samples, incorporating sample preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric detection, and data analysis components essential for reliable biomarker quantification.

Research Reagent Solutions for LPO Analysis

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Lipid Peroxidation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant Preservatives | Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), EDTA | Prevent ex vivo oxidation during sample processing | Critical for accurate measurement of endogenous LPO; typically used at 0.1% concentration [23] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Thiobarbituric acid (TBA), DNPH, PFB-Br | Enhance detection sensitivity and chromatographic behavior | TBA for MDA; DNPH for carbonyls; PFB-Br for GC-MS analysis [19] [23] |

| Internal Standards | d8-4-HNE, d4-9-HODE, 8-iso-PGF2α-d4 | Quantification correction for matrix effects and recovery | Isotope-labeled analogs for each LPO class ensure accurate quantification [6] [28] |

| SPE Sorbents | HLB, C18, Silica | Extract and concentrate LPO products from complex matrices | HLB provides broad-spectrum extraction for diverse LPO products [23] [28] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | COX inhibitors (indomethacin), LOX inhibitors (NDGA) | Distinguish enzymatic vs. non-enzymatic LPO pathways | Useful for mechanistic studies in cellular models [9] |

| LC-MS Mobile Phase Additives | Formic acid, ammonium formate | Enhance ionization efficiency and control adduct formation | Concentration optimization critical for sensitivity and reproducibility [28] |

Quality Control and Method Validation

Robust analysis of LPO products requires comprehensive quality control procedures to ensure data reliability. Method validation should establish linearity, sensitivity, precision, accuracy, and recovery for each analyte [19] [6]. Quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations should be analyzed with each batch to monitor performance. For targeted analyses, the use of scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) enhances sensitivity and enables monitoring of numerous transitions in a single chromatographic run [19].

Matrix effects must be carefully evaluated by comparing the response of standards in neat solution versus spiked matrix [6]. Signal suppression or enhancement can be corrected using appropriate internal standards. Stability studies should assess short-term bench top stability, freeze-thaw stability, and long-term storage stability under the employed conditions [28].

For laboratories implementing these methods, participation in inter-laboratory comparison programs and analysis of standard reference materials (when available) provides additional validation of analytical performance. These rigorous quality assurance measures are particularly important when comparing LPO product levels across different studies or when establishing clinical reference ranges [19] [6].

The epilipidome represents an expanded collective of enzymatically or non-enzymatically modified lipids, introducing a new level of structural and functional complexity to biological systems analogous to epigenetic and post-translational modifications of proteins [29] [30]. This diverse landscape of modified lipids includes species generated through oxidation, nitration, sulfation, and halogenation [31] [30]. Among these modifications, lipid oxidation attracts significant attention due to its profound implications in regulating inflammation, cell proliferation, and death programs [9] [28]. The epilipidome is not merely a collection of lipid "waste" but constitutes key players in regulating cellular metabolism, function, and death, with their generation being tightly controlled in response to extra- and intracellular stimuli at defined locations [29] [30].

Lipid peroxidation products (LPPs) demonstrate remarkable structural heterogeneity, ranging from species addition (hydroperoxides, epoxides) to truncated fatty acid cleavage products (alkenals, alkanals, hydroxyalkenals) [32]. These modifications occur at energetically favorable sites of the lipid molecule, with double bonds representing the most susceptible sites to electrophilic addition in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), while allylic and bis-allylic positions are prone to radical attack [31]. The resulting modified lipids actively regulate complex biological processes, making the epilipidome a critical component in understanding cellular physiology and pathology.

Table 1: Major Classes of Lipid Oxidation Products and Their Biological Significance

| Class of Oxidized Lipid | Examples | Formation Pathways | Biological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Aldehydes | Malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) | Non-enzymatic peroxidation of PUFAs | Protein adduct formation, inflammation, cytotoxicity [27] |

| Enzymatically Oxidized Complex Lipids | Oxidized phosphatidylcholines (oxPC), oxidized cholesteryl esters (oxCE) | Lipoxygenases, cyclooxygenases, cytochrome P450 | Signaling mediators, inflammation resolution [28] |

| Headgroup-modified Lipids | N-chloraminated phosphatidylethanolamines | Hypochlorous acid-mediated chlorination | Membrane property alteration, signaling [32] |

Biological Significance in Cell Signaling and Death

Role in Inflammation and Cellular Signaling

Lipid oxidation products demonstrate context-dependent bioactivities, functioning as both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators [33] [28]. During inflammatory processes, oxidized lipids accumulate and induce specific cellular reactions that modulate the inflammatory progression, potentially determining the fate and outcome of the body's reaction in acute inflammation during host defense [33]. The anti-inflammatory actions of oxidized lipids include: (1) induction of signaling pathways leading to the upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes; (2) inhibition of signaling pathways coupled to the expression of proinflammatory genes; and (3) preventing the interaction of proinflammatory bacterial products with host cells [33].

Oxidized lipoproteins and lipid oxidation products recognize and activate a wide range of pattern recognition receptors including macrophage scavenger receptors, Toll-like receptors, CD36, and C-reactive protein [28]. Furthermore, oxidized lipids and their protein adducts can be recognized by natural IgM antibodies and sequestered from circulation, contributing to immune modulation [28]. The inflammation-modulating potential of esterified oxylipins in complex lipids is increasingly recognized as a significant component of endocrine signaling, with characteristic epilipidomic signatures differing dramatically between lean and obese individuals [28].

Role in Regulated Cell Death

Lipid peroxidation is a common feature across multiple modalities of regulated cell death (RCD), including ferroptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and apoptosis [9]. Excessive lipid peroxidation contributes to plasma membrane damage by altering membrane assembly, composition, structure, and dynamics, ultimately triggering cell death programs [9] [34].

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death, features excessive peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-containing membrane phospholipids as its hallmark [9] [34]. In the presence of bioactive iron, membrane phospholipids are converted to phospholipid-hydroperoxides through enzymatic or nonenzymatic lipid peroxidation mechanisms. The continued auto-oxidation of phospholipids increases membrane curvature, stimulates oxidative micellization, pore formation, and subsequent cell membrane damage [9]. Specific lipid peroxidation products, such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), contribute significantly to the progression of various RCD types by forming covalent adducts with proteins, phospholipids, and nucleic acids, thereby disrupting their normal functions [27] [34].

Figure 1: Epilipidome in Cellular Signaling and Fate Decisions. Lipid oxidation products influence cell fate through multiple signaling pathways, leading to either adaptive responses or regulated cell death depending on the extent of oxidation and cellular context.

Analytical Challenges in Epilipidomics

Comprehensive analysis of the epilipidome faces significant technical challenges due to the intrinsic chemical complexity of modified lipids, which presents both analytical and computational obstacles [31]. These challenges include:

Low Abundance: Epilipids generally occur with inherently low abundance and transient nature within biological systems, with absolute amounts/concentrations of lipid oxidation products estimated at only 0.03-3.0 mol % of the total non-oxidized lipidome [31]. This low abundance places significant demands on instrumental sensitivity and requires specialized sample preparation and enrichment strategies.

High Structural Diversity: The remarkable structural diversity of lipids, combined with the large number of potential modification sites and types of possible reactions, creates an enormous number of chemically distinct derivatives [31]. Knowledge-based algorithms estimate possible product spaces with less than 10âµ enumerated structures, still representing substantial analytical complexity [31].

Isomer Complexity: The vast chemical space covered by the epilipidome results in a significant number of isobaric (same nominal mass) and isomeric (same exact mass) species [31]. High-resolution mass spectrometry systems can distinguish isobaric species, but structural isomers with identical exact mass and isotopic patterns require additional separation techniques or fragmentation analysis for confident annotation.

Non-standard Fragmentation: The fragmentation patterns of epilipids often differ significantly from those of parent molecules, complicating library-based identification [31]. Even small modifications in lipid chemical structure can produce substantial differences in MS/MS fragmentation, limiting the utility of conventional lipid MS/MS libraries for epilipid identification.

Nomenclature Inconsistencies: A unified nomenclature scheme for modified lipid species throughout all lipid categories is still lacking, leading to improper annotation and over-reporting in research literature [31]. Different names for the same compound reduce the usability of reference data and complicate unified computational treatment of lipid names.

Table 2: Major Analytical Challenges in Epilipidomics and Potential Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | Potential Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance | Signals near instrumental detection limits; ion suppression effects | LC separation prior to MS; selective enrichment; optimized ionization |

| Structural Diversity | Enormous number of potential analytes; unpredictable modifications | Biological intelligence-driven in silico prediction; targeted methods |

| Isomer Complexity | Confident annotation requires orthogonal separation | High-resolution MS; ion mobility spectrometry; retention time prediction |

| Non-standard Fragmentation | Limited reference libraries; inaccurate identification | Elevated energy HCD; diagnostic fragment mapping; computational prediction |

| Dynamic Range | Wide concentration range of precursors and products | Multi-platform approaches; selective enrichment; sensitivity optimization |

LC-MS/MS Analytical Workflow

Sample Preparation and Liquid Chromatography

Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) currently represents the technique of choice for epilipidome studies due to its ability to reduce ion suppression effects and increase the overall dynamic range for low-abundance analytes [31]. The sample preparation workflow must be optimized to preserve the integrity of oxidized lipids while removing potential interferents. For blood plasma analysis, protein precipitation with cold organic solvents (e.g., methanol or methyl tert-butyl ether) is commonly employed, followed by solid-phase extraction for further cleanup and enrichment of oxidized lipids [28].

Liquid chromatography separation typically employs reversed-phase C18 columns with gradient elution using water and organic modifiers (acetonitrile or methanol), often with acidic additives (formic acid or ammonium formate) to enhance ionization efficiency [28]. The chromatographic conditions must be optimized to resolve the numerous structural isomers present in the epilipidome, potentially requiring longer analytical columns or specialized stationary phases for challenging separations.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

High-resolution mass spectrometry provides the mass accuracy and resolving power necessary for confident elemental composition assignment of oxidized lipids [31] [28]. Both positive and negative ion mode electrospray ionization are typically employed to capture the diverse chemical properties of different oxidized lipid classes. Data-dependent acquisition methods are commonly used, where the most abundant ions in survey scans are selected for fragmentation.

For structural characterization, elevated energy higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) generates informative fragment ions that reveal modification type and position without the need for multistage fragmentation [28]. Stepped normalized collision energy (e.g., 20-30-40 units) has been shown to provide comprehensive fragmentation patterns containing lipid class-specific, molecular species, modification type, and modification position information [28].

Figure 2: LC-MS/MS Workflow for Epilipidomics Analysis. The analytical pipeline encompasses sample preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric analysis, and computational processing for comprehensive oxidized lipid profiling.

Data Processing and Annotation

Accurate annotation of oxidized lipids requires a combination of bioinformatics and LC-MS/MS technologies to support identification and relative quantification in a modification type- and position-specific manner [28]. The data processing workflow includes:

Feature Detection: Using specialized software (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) to extract ion chromatograms and detect features from raw LC-MS data, with careful attention to noise threshold settings to capture low-abundance oxidized lipids [31].

Lipid Identification: Matching accurate mass and fragmentation patterns against in silico predicted epilipidome databases and applying fragmentation rules compiled from oxidized lipid standards and literature data [28]. Diagnostic fragment ions enable determination of modification type and position along acyl chains.

Relative Quantification: Integrating peak areas for identified oxidized lipids across sample groups, typically using internal standards for normalization when available [28].

The development of fragmentation rules for different modification types and positions on oxidized acyl chains provides a framework for high-throughput annotation of oxidized glycerophospholipids, cholesteryl esters, and triglycerides [28]. These rules are continually expanded as new oxidized lipid standards become available and more fragmentation data are accumulated in public repositories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Epilipidomics Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cold Atmospheric Plasma | Pro-oxidant tool to promote LPP formation via controlled reactive species delivery [32] | Gas composition (Ar/Oâ‚‚/Nâ‚‚) adjustable to modulate reactive species profile; enables mechanistic studies |

| Liposome Biomimetic Models | Simplified membrane systems to deconvolute effects on single lipid scale [32] | Composite liposomes (POPC/SM/PE) predict modification outcomes; control membrane composition |

| Heavy Oxygen Isotope (¹â¸O) | Mass spectrometry detectable tracer for studying lipid peroxidation mechanisms [32] | ¹â¸Oâ‚‚ in feed gas or H₂¹â¸O in liquid traces oxygen incorporation; reveals peroxidation pathways |

| Oxidized Lipid Standards | Reference compounds for method development and quantification [28] | Limited commercial availability; in vitro oxidation often required to generate broader standard sets |

| LC-MS/MS with HCD | Analytical platform for separation, detection, and structural characterization [28] | High-resolution instrument essential; stepped collision energy improves fragmentation information |

| K-Ras-IN-1 | K-Ras-IN-1, MF:C11H13NOS, MW:207.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BoNT-IN-1 | BoNT-IN-1|Botulinum Neurotoxin Inhibitor | BoNT-IN-1 is a high-quality small molecule inhibitor of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) for research use. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Applications in Disease Research

Epilipidomics approaches have revealed significant alterations in oxidized lipid profiles in various disease states, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential diagnostic biomarkers. In metabolic disorders, the characteristic epilipidome signature of lean individuals, dominated by modified octadecanoid acyl chains in phospho- and neutral lipids, shifts dramatically toward lipid peroxidation-driven accumulation of oxidized eicosanoids in obese individuals with and without type 2 diabetes [28]. This shift suggests significant alteration of endocrine signaling by oxidized lipids in metabolic disorders.

In cardiovascular diseases, repeated consumption of thermally oxidized cooking oils impairs antioxidant capacity and leads to oxidative stress and inflammation, contributing to hypertension and atherosclerosis [27]. Toxic lipid oxidation products such as malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal activate inflammatory pathways, increasing expression of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) and pro-inflammatory cytokines in vascular tissues [27].

The central nervous system is particularly vulnerable to lipid peroxidation due to its high lipid content and oxygen consumption. Lipid peroxides are recognized as key mediators in neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease, where they contribute to neuronal damage and disease progression [34] [32]. Similarly, in cancer biology, oxidative lipid modifications influence tumor development and progression, with emerging evidence supporting their role in regulating cell death pathways such as ferroptosis, which represents a promising therapeutic avenue for inducing cancer cell death [9] [34].

The growing understanding of epilipidome alterations in human diseases highlights the potential of oxidized lipids as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The development of robust LC-MS/MS workflows for epilipidome analysis will facilitate the translation of these findings into clinical applications, enabling precision medicine approaches based on individual oxlipidomic signatures.

Advanced LC-MS/MS Workflows for Lipid Peroxidation Product Analysis

Sample Preparation Strategies for Different Biological Matrices

Sample preparation is a critical preliminary step in bioanalysis, significantly influencing the accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability of subsequent Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) results. The primary goals are to extract target analytes, remove interfering matrix components, and ensure analyte stability, thereby minimizing matrix effects that can suppress or enhance ion signals [35]. This is particularly crucial for the analysis of lipid peroxidation products, such as lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs), which are unstable, present in low abundances, and exhibit poor ionization efficiency [36]. The complexity of biological matrices—each with a unique composition of proteins, lipids, salts, and other endogenous compounds—demands tailored preparation strategies. This article provides application notes and detailed protocols for preparing various biological matrices within the context of a thesis focused on the LC-MS/MS analysis of lipid peroxidation products in inflammation research.

Biological Matrices: Challenges and Preparation Strategies

The choice of biological matrix directly impacts the sample preparation approach. Each matrix presents distinct challenges and requires specific handling and preparation techniques to accurately profile labile lipid peroxidation biomarkers.

Table 1: Biological Matrices in Bioanalysis: Composition, Challenges, and Preparation Considerations

| Biological Matrix | Key Compositional Features | Primary Challenges for LC-MS/MS Analysis | Sample Preparation Considerations for Lipid Peroxidation Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum/Plasma [35] | Water, proteins, glucose, hormones, minerals, phospholipids. | High protein and phospholipid content causes significant matrix effects. | Deproteinization; phospholipid removal; stabilization of hydroperoxides. |

| Urine [35] | ~95% water, inorganic salts (sodium, phosphate), urea, creatinine. | High salt concentration; variable viscosity and dilution. | Dilution; salt removal; potential enrichment of low-abundance analytes. |

| Tissue [37] [35] | Group of cells (soft: liver, kidney; tough: muscle; hard: bone). | Cellular complexity; heterogeneity; requiring homogenization. | Snap-freezing is preferred over FFPE for labile analytes; homogenization. |

| Saliva/Oral Fluid [38] | Water, bacteria, food particles, additives from collection kits. | Collection buffer additives (preservatives, surfactants) cause matrix effects. | Effective sample clean-up to remove buffer additives is essential. |

| Hair [35] | Keratin, stable and tough matrix. | Low analyte concentration; external contamination. | Washing, digestion, or extraction to incorporate analytes into the analysis. |