Longitudinal In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging of Inflammation: Techniques, Applications, and Optimization for Preclinical Research

Longitudinal in vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) has emerged as a powerful non-invasive technology for monitoring inflammatory processes in real-time within living organisms.

Longitudinal In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging of Inflammation: Techniques, Applications, and Optimization for Preclinical Research

Abstract

Longitudinal in vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) has emerged as a powerful non-invasive technology for monitoring inflammatory processes in real-time within living organisms. This comprehensive review explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, optimization strategies, and validation approaches for BLI in inflammation research. We examine how BLI enables researchers to track spatial and temporal dynamics of immune responses, distinguish between acute and chronic inflammation phases, and evaluate therapeutic efficacy in disease models ranging from infectious diseases to cancer and autoimmune disorders. By synthesizing current methodologies and addressing common technical challenges, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical insights for implementing robust BLI protocols in preclinical studies, ultimately facilitating more efficient therapeutic development and reducing animal usage through longitudinal study designs.

Understanding Bioluminescence Imaging: Core Principles and Biological Basis of Inflammation Monitoring

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) has become an indispensable tool for longitudinal in vivo studies of inflammatory processes, enabling non-invasive monitoring of biological phenomena in live animal models. This technology relies on the enzymatic reaction between luciferase enzymes and their substrates (luciferins) to produce light without the need for external excitation. Unlike fluorescence imaging, BLI offers near-zero background, superior signal-to-noise ratio, and high sensitivity for deep-tissue imaging, making it particularly valuable for tracking inflammation over time [1] [2]. The fundamental principle involves luciferase-catalyzed oxidation of luciferin, requiring oxygen and sometimes co-factors like ATP, resulting in an excited-state intermediate that emits light upon returning to its ground state [3] [1]. This application note details the core mechanisms, optimized protocols, and practical implementation of BLI for inflammation research, providing scientists with the foundational knowledge needed to design robust longitudinal studies.

Fundamental Reaction Mechanisms and Systems

Core Biochemical Reaction

The bioluminescence reaction is a biochemical process where luciferase catalyzes the oxidation of a luciferin substrate, leading to photon emission. The general reaction requires three key components: the enzyme luciferase, the substrate luciferin, and molecular oxygen (O₂). Some systems additionally require cofactors such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and Mg²⺠ions [3] [1] [4]. The reaction mechanism proceeds through several key steps:

- Activation: Luciferin is adenylated by ATP in the active site of luciferase, forming luciferyl-adenylate.

- Oxidation: The adenylated intermediate reacts with molecular oxygen, forming a high-energy, cyclic dioxetanoine intermediate.

- Light Emission: The decomposition of this intermediate produces excited-state oxyluciferin, which emits light as it returns to its ground state [3] [5].

The color of the emitted light is determined by the structure of the oxyluciferin and the specific luciferase enzyme, with emission spectra ranging from blue to red [5].

Major Bioluminescence Systems and Their Characteristics

While numerous bioluminescent systems exist in nature, a few have been optimized and are widely used in biomedical research. The table below summarizes the key features of the primary systems applied in inflammation imaging.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Bioluminescence Systems

| System | Luciferase Source | Luciferin | Cofactors Required | Peak Emission Wavelength | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly (Fluc) | Photinus pyralis (Firefly) | D-Luciferin | ATP, Mg²âº, Oâ‚‚ | 550-620 nm (pH-dependent) [3] [1] | High quantum yield; glow-type kinetics; ideal for deep-tissue imaging due to yellow-red light [3] [1]. |

| Click Beetle | Pyrophorus plagiophthalamus | D-Luciferin | ATP, Mg²âº, Oâ‚‚ | 537-593 nm [3] | Tolerant to broad pH range; engineered variants emit different colors for multiplexing [3]. |

| Renilla (Rluc) | Renilla reniformis (Sea pansy) | Coelenterazine | Oâ‚‚ | ~480 nm [3] [1] | Small, cytosolic enzyme; flash-type kinetics; does not require ATP [3] [1]. |

| Gaussia (Gluc) | Gaussia princeps (Copepod) | Coelenterazine | Oâ‚‚ | ~480 nm [3] [1] | Naturally secreted; very bright; high thermostability; flash-type kinetics [3] [1]. |

| NanoLuc (Nluc) | Oplophorus gracilirostris (Shrimp) | Furimazine (engineered coelenterazine) | Oâ‚‚ | ~460 nm [3] | Small size (19 kDa); exceptionally bright; high stability; useful for protein-protein interaction studies [3]. |

Diagram 1: Core luciferase-luciferin reaction pathway leading to light emission.

Quantitative Data and Kinetics for Experimental Design

Understanding the kinetic properties of different luciferase systems is critical for designing sensitive and reproducible experiments, especially for quantifying inflammatory responses over time.

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters and Operational Characteristics for Experimental Planning

| Luciferase | Reaction Kinetics | Optimal Substrate Administration for In Vivo Imaging | Signal Peak & Duration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly (Fluc) | Glow-type [1] | Intraperitoneal (IP) injection of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg) [1] | Peaks at ~10 min; stable for ~30 min [1] | Signal is ATP-dependent; light output can be used to monitor cellular metabolic activity [3]. |

| Renilla (Rluc) / Gaussia (Gluc) | Flash-type [1] | Intravenous (IV) injection of coelenterazine [1] | Peaks within seconds; rapid decay [1] | Imaging must be performed immediately after substrate injection. Coelenterazine has poor aqueous solubility [1]. |

| NanoLuc (Nluc) | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Very high brightness and stability; uses a synthetic furimazine substrate [3]. |

The firefly luciferase reaction follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The reaction rate and final light output are dependent on the concentrations of enzyme, substrate (D-luciferin), and essential co-factors (ATP, Mg²âº, Oâ‚‚) [4] [6]. It is important to note that the firefly luciferase reaction can be subject to product inhibition, where the accumulation of oxyluciferin or other byproducts can reduce light output over time [4]. Furthermore, ionizing radiation has been shown to affect the reaction rate, primarily by eliminating dissolved oxygen, with a dose constant for oxygen removal of approximately 70 Gy [4].

Application Protocol: Imaging Caspase-8 in Programmable Cell Death

Inflammation research often involves monitoring programmed cell death (e.g., apoptosis, pyroptosis). This protocol details the use of a Caspase-8-activated bioluminescence probe for sensitive in vivo imaging of this key inflammatory process [2].

Principle

The probe, Ac-IETD-Amluc, is designed to be "off" until it encounters activated Caspase-8, a key regulator of apoptosis and pyroptosis. The probe consists of:

- A tetrapeptide substrate (Ac-IETD) recognized and cleaved specifically by Caspase-8.

- A D-Aminoluciferin (Amluc) motif, which is a substrate for firefly luciferase (fLuc) but is caged and non-emissive in the intact probe.

Upon cleavage by Caspase-8, the Amluc motif is released. In cells expressing fLuc, the free Amluc is oxidized, producing a bioluminescence signal that reports the location and activity of Caspase-8 [2].

Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Caspase-8 Activation Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Ac-IETD-Amluc Probe | Caspase-8-activated bioluminescent probe; the core diagnostic agent. |

| Firefly Luciferase (fLuc) | Reporting enzyme; can be expressed in cells via stable or transient transfection. |

| Cisplatin or other apoptogens | Chemical inducer of apoptosis (positive control). |

| D-Luciferin | Native substrate for firefly luciferase; used for background signal comparison. |

| In Vivo Imager | System equipped with a sensitive CCD camera for detecting low-light bioluminescence. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Line Preparation: Use a cell line (e.g., 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cells) stably expressing firefly luciferase (fLuc-4T1) [2].

- Apoptosis Induction: Treat fLuc-4T1 cells with cisplatin (e.g., 20 µM for 12 hours) to trigger Caspase-8-mediated apoptosis [2].

- In Vitro Validation:

- Incubate the Ac-IETD-Amluc probe (200 µM) with recombinant Caspase-8 (5 µg/mL) in reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM DTT, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.5) at 37°C for 1-2 hours [2].

- Confirm cleavage and light emission using a luminometer or imager.

- In Vivo Imaging:

- Establish tumors in animal models by injecting fLuc-4T1 cells.

- Induce apoptosis in vivo via systemic administration of cisplatin.

- Inject the Ac-IETD-Amluc probe intravenously into the subject.

- Acquire bioluminescence images using an in vivo imaging system. The signal generated is specific to the sites of Caspase-8 activation.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

The bioluminescence signal from the Ac-IETD-Amluc probe shows a linear relationship with Caspase-8 concentration (Y = 1.163 + 2.107X, R² = 0.96), with a calculated detection limit of 0.082 µg/L for Caspase-8 [2]. This quantitative relationship allows for longitudinal monitoring of changes in programmed cell death activity in response to therapeutic interventions.

Diagram 2: Caspase-8 probe activation pathway for imaging cell death.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of bioluminescence imaging relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential solutions for the field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioluminescence Imaging

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| D-Luciferin (synthetic) [7] | Substrate for firefly and click beetle luciferases; essential for in vivo imaging with Fluc. |

| Coelenterazine (native & analogs) [1] | Substrate for Renilla, Gaussia, and NanoLuc luciferases. Analogs like Viviren and Enduren offer higher stability or sensitivity. |

| Caspase-8 Activated Probe (e.g., Ac-IETD-Amluc) [2] | Smart probe for specific detection of apoptosis/pyroptosis in vivo. |

| Recombinant Luciferases (Fluc, Rluc, Gluc, Nluc) [3] | Enzymes for in vitro assay development, probe validation, and standardization. |

| Stable Luciferase-Expressing Cell Lines | Ready-to-use cellular models for studying inflammation, cancer progression, and drug efficacy in vivo. |

| Bioluminescence-Compatible Matrigel | Medium for housing cells during subcutaneous tumor implantation, ensuring reliable bioluminescence signal development. |

| Methscopolamine bromide | Methscopolamine bromide, CAS:155-41-9, MF:C18H24BrNO4, MW:398.3 g/mol |

| Methylthiouracil | Methylthiouracil|Antithyroid Agent|CAS 56-04-2 |

The fundamental mechanisms of luciferase-luciferin reactions provide a powerful foundation for sensitive optical imaging in live animal models of inflammation. The D-luciferin-dependent firefly system remains a cornerstone for deep-tissue imaging due to its favorable emission wavelength and glow-type kinetics, while coelenterazine-dependent systems like NanoLuc offer exceptional brightness for highly sensitive applications. The development of activatable probes, such as the Caspase-8-sensitive Ac-IETD-Amluc, exemplifies how these fundamental principles can be leveraged to create specific molecular tools for monitoring key inflammatory processes like programmed cell death. By adhering to optimized protocols and understanding the kinetic properties of these systems, researchers can robustly apply bioluminescence imaging to longitudinally track disease progression and therapeutic responses in vivo, thereby accelerating drug development for inflammatory diseases.

Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) represents a pivotal coordinator of innate and adaptive immune responses, functioning as a master regulator of inflammation and a critical molecular target in cancer biology. Initially identified in B lymphocytes, NF-κB is activated by a diverse range of stimuli including proinflammatory cytokines, bacterial and viral products, and cellular stresses [8] [9]. The reciprocal activation between NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines creates a fundamental signaling loop that drives inflammation-associated cancer development [8]. In cancer biology, NF-κB activation promotes cell survival, proliferation, and resistance to anticancer therapies, making it a promising target for therapeutic intervention [8] [9]. This application note details advanced methodologies for investigating NF-κB activation pathways and tracking immune responses, with particular emphasis on longitudinal in vivo bioluminescence imaging techniques that enable real-time monitoring of inflammatory processes in live animal models.

Molecular Composition and Activation Pathways of NF-κB

NF-κB Protein Family and Regulatory Components

The NF-κB signaling system consists of a sophisticated network of proteins and regulatory elements that collectively control its transcriptional activity:

NF-κB Transcription Factor Family: Five members form this family: p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, p50/p105 (NF-κB1), and p52 (NF-κB2). These proteins contain a Rel homology domain (RHD) responsible for dimerization, DNA binding, and association with inhibitory IκB proteins. The p65, RelB, and c-Rel subunits possess C-terminal transactivation domains (TAD) that interact with transcriptional machinery, while p50 and p52 homodimers lacking TADs can function as transcriptional repressors [8] [9].

IκB Inhibitor Family: Seven known members (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBγ, IκBε, BCL-3, and precursor proteins p105 and p100) sequester NF-κB dimers in the cytoplasm through ankyrin repeat domains that mask nuclear localization signals. IκB proteins undergo signal-induced phosphorylation and degradation to activate NF-κB signaling [8] [9].

IKK Kinase Complex: The IκB kinase complex contains two catalytic subunits (IKKα/IKK1 and IKKβ/IKK2) and a regulatory subunit (IKKγ/NEMO). IKKβ serves as the primary catalytic subunit for the canonical pathway, while IKKα mediates the non-canonical pathway [8] [9].

NF-κB Activation Pathways

NF-κB activation occurs through distinct signaling pathways that respond to different extracellular stimuli:

Figure 1: NF-κB Activation Pathways. The diagram illustrates the canonical, non-canonical, and atypical NF-κB activation mechanisms in response to various stimuli.

Canonical (Classical) Pathway: This major activation route involves IKKβ-catalyzed phosphorylation of IκB proteins, particularly in response to proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and cellular stresses. TNF-α binding to its receptor recruits IKK to the TNFR1 signaling complex through TRAF2 and RIP1. K63 ubiquitination of RIP by E3 ubiquitin ligases cIAP-1 and cIAP-2 creates a platform for IKK recruitment and activation via MEKK3 or TAK1-mediated phosphorylation. Activated IKKβ phosphorylates IκB at serine residues 32 and 36, triggering polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This process exposes nuclear localization signals on p65 and p50, enabling nuclear translocation and activation of target genes [8] [9].

Non-canonical Pathway: Activated by specific TNF receptor family members (CD40, LTβ, BAF) and viral proteins such as Epstein-Barr virus LMP-1, this pathway depends on NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)-mediated activation of IKKα. Activated IKKα triggers phosphorylation and processing of p100 to p52, which then forms a transcriptionally active complex with RelB that translocates to the nucleus. Interestingly, cIAP proteins that promote the canonical pathway negatively regulate the non-canonical pathway by triggering NIK ubiquitination and degradation [8].

Atypical Pathways: Certain stimuli activate NF-κB through IKK-independent mechanisms. Short-wavelength UV light induces casein kinase 2 (CK2)-mediated phosphorylation and calpain-dependent IκB degradation, while hydrogen peroxide activates NF-κB through tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB at Tyr42 via c-Src or Syk kinases [8].

Quantitative Assessment of NF-κB Pathway Activity

Signal Transduction Pathway Activity Profiling

Recent technological advances enable quantitative measurement of NF-κB signaling activity in immune cells. The Simultaneous Transcriptome-based Activity Profiling of Signal Transduction Pathways (STAP-STP) technology simultaneously measures activity of nine relevant signal transduction pathways (including NF-κB) in immune cells based on mRNA analysis of target genes [10].

Table 1: Signal Transduction Pathway Activity in Resting vs. Activated Immune Cells

| Immune Cell Type | Activation State | NF-κB Pathway Activity | PI3K-FOXO Activity | JAK-STAT3 Activity | Key Activators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cells | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| CD4+ T cells | Activated (Th1) | High | High | High | Anti-CD3/CD28, IL-12 |

| CD8+ T cells | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| CD8+ T cells | Activated | Moderate | High | Moderate | Antigen-specific activation |

| B cells | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| B cells | Activated | High | High | Moderate | Anti-IgM |

| Monocytes | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| Monocytes | Activated | High | Moderate | High | TNF-α, IFN-α2a, IFN-γ |

| Macrophages | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| Macrophages | Activated | High | Moderate | High | LPS (100 ng/mL) |

| Natural Killer cells | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| Natural Killer cells | Activated | Moderate | High | High | IFN-α (1-100 ng/mL) |

| Dendritic cells | Resting | Low | Low | Low | - |

| Dendritic cells | Activated | High | Moderate | High | Newcastle Disease Virus |

This methodology reveals that each immune cell type displays a characteristic signal transduction pathway activity profile (SAP) that reflects both cell lineage and activation status. Analysis of rheumatoid arthritis patients using this technology demonstrated increased TGFβ pathway activity in whole blood samples, highlighting its clinical utility for monitoring immune dysfunction in inflammatory diseases [10].

Bioluminescence Imaging for NF-κB Activity Monitoring

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) provides a noninvasive approach for longitudinal monitoring of NF-κB activation in live animal models. This technology utilizes transgenic mice carrying luciferase reporter genes under the control of NF-κB-responsive elements, enabling real-time assessment of inflammatory responses through in vivo imaging systems [11] [12].

Table 2: Bioluminescence Signal Intensity in Mouse Models of Inflammation

| Disease Model | Baseline Bioluminescence (photons/sec) | Peak Inflammation Bioluminescence (photons/sec) | Fold Increase | P-value | Imaging Time Post-Induction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primed Mycobacterial Uveitis (PMU) | 1.47×10ⴠ| 1.46×10ⵠ| 9.9 | 0.01 | Day 2 |

| Endotoxin-Induced Uveitis (EIU) | 1.09×10ⴠ| 3.18×10ⴠ| 2.9 | 0.04 | 18 hours |

| Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis (EAU) | Not significant | Not significant | - | NS | Days 15-21 |

| Autoimmune Disease Model | Variable baseline | Significant increase in diseased organs | - | <0.05 | Preclinical phase |

The sensitivity of NF-κB bioluminescence imaging enables detection of subclinical disease activity before onset of clinical symptoms and autoantibody production. In autoimmune models, bioluminescence signals emerge from secondary lymphoid organs, inflamed intestines, skin lesions, and arthritic joints, correlating with disease progression and permitting evaluation of anti-inflammatory interventions [11].

Experimental Protocols for NF-κB Imaging and Immune Cell Tracking

Protocol: Longitudinal NF-κB Bioluminescence Imaging in Transgenic Mice

Purpose: To monitor NF-κB activation in real-time using transgenic mice with NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporters.

Materials:

- NF-κB-luciferase transgenic mice (FVB background)

- D-luciferin potassium salt (15 mg/mL in PBS)

- In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS Spectrum, PerkinElmer)

- Isoflurane anesthesia system

- Heating pad or IVIS warming stage

- Depilatory cream for hair removal

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize mice using isoflurane (2.5-3% induction, 1.5-2% maintenance). Apply ophthalmic ointment to prevent corneal drying. Remove hair from imaging area using depilatory cream to minimize light absorption.

- Substrate Administration: Inject D-luciferin intraperitoneally (150 mg/kg body weight) using sterile technique. Alternatively, intravenous injection via tail vein provides brighter initial signal with more rapid decay.

- Image Acquisition: Place animals in IVIS chamber maintained at 37°C. Position animals to ensure optimal orientation for region of interest. Acquire images 10-15 minutes post-injection for peak signal intensity using field of view "A," subject height 1.5 cm, with medium binning for 5-minute exposure periods.

- Image Analysis: Quantify bioluminescence signal using Living Image software or similar platform. Draw regions of interest (ROI) around signal areas and calculate total flux (photons/second). Normalize values to baseline measurements.

- Longitudinal Timing: Perform imaging at consistent time points post-intervention. For acute inflammation models (EIU, PMU), image at 18-48 hours. For chronic models (EAU), monitor weekly for 3-4 weeks.

Technical Considerations:

- Intraperitoneal luciferin injection provides more stable signal than IV with peak at 10-15 minutes post-injection.

- Consistent positioning is critical for reproducible ROI analysis.

- Background subtraction using control regions ensures accurate quantification [13] [11] [14].

Protocol: Immune Cell Migration and Tracking Analysis

Purpose: To quantify immune cell migration dynamics using advanced computational tracking methods.

Materials:

- Time-lapse microscopy system with environmental control

- celltrackR R package (available on CRAN and GitHub)

- Immune cells of interest (T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages)

- Appropriate culture media and migration chambers

- Fluorescent labeling reagents (optional)

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup: Prepare immune cells in appropriate migration assay system (Boyden chamber, collagen matrix, or similar). Maintain constant temperature (37°C) and CO₂ (5%) throughout imaging.

- Image Acquisition: Capture time-lapse images at 30-60 second intervals for 2-4 hours using 10-20× objectives. Ensure adequate resolution for single-cell tracking while minimizing phototoxicity.

- Cell Tracking: Import image sequences into celltrackR package. Pre-process images to correct for drift and background noise. Use automated tracking algorithms to generate cell trajectories.

- Quality Control: Implement package quality control measures to identify and exclude tracking artifacts. Filter tracks based on duration and displacement thresholds.

- Migration Analysis: Calculate migration parameters including mean velocity, persistence, turning angle distribution, and confinement ratio. Compare experimental conditions using statistical methods provided in package.

- Data Visualization: Generate rose plots, displacement graphs, and track overlays to visualize migration patterns. Perform cluster analysis to identify distinct migration phenotypes.

Technical Considerations:

- celltrackR supports both 2D and 3D migration analysis

- The package includes simulation tools for modeling cell migration

- Method corrects for common imaging artifacts and biases [15]

Protocol: Assessment of Host-Biomaterial Interactions via NF-κB Imaging

Purpose: To evaluate inflammatory responses to implanted biomaterials using NF-κB bioluminescence imaging.

Materials:

- NF-κB-luciferase transgenic mice

- Biomaterial of interest (e.g., genipin-cross-linked gelatin conduit)

- Sterile surgical instruments

- D-luciferin substrate

- IVIS imaging system

Procedure:

- Biomaterial Preparation: Sterilize biomaterial implants according to established protocols. For infection modeling, immerse materials in LPS solution (100 ng/mL) for endotoxin exposure.

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize mice and perform aseptic implantation of biomaterials in subcutaneous dorsal pockets. Close incisions with sterile sutures or wound clips.

- Longitudinal Imaging: Image mice pre-implantation for baseline and at regular intervals post-implantation (days 1, 3, 7, 14). Follow standard bioluminescence imaging protocol with D-luciferin injection.

- Histological Correlation: Following final imaging time point, euthanize animals and harvest implant sites for histological analysis. Process tissues for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry using antibodies against luciferase and inflammatory markers.

- Data Correlation: Compare bioluminescence signals with histological evidence of inflammation (immune cell infiltration, tissue damage). Statistical analysis should correlate imaging data with conventional inflammation metrics.

Applications: This protocol enables real-time assessment of host-biomaterial interactions, evaluation of biocompatibility, and screening of anti-inflammatory biomaterial coatings [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NF-κB and Immune Cell Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Products/Specifications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) | Primary bioluminescent reporter for in vivo imaging | VivoGlo Luciferin, In Vivo Grade | ATP-dependent; peak emission 562 nm; ideal for tumor models |

| NanoLuc (NLuc) | Small, bright ATP-independent reporter | Nano-Glo Fluorofurimazine In Vivo Substrate (FFz) | 19kDa size; blue light (460 nm); better for surface imaging |

| Akaluc/AkaLumine | Red-shifted variant for enhanced tissue penetration | Akaluc/AkaLumine system | Improved tissue penetration; higher signal intensity |

| Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) | Multiplexing with other reporters | ViviRen In Vivo Renilla Luciferase Substrate | Coelenterazine substrate; blue light (480 nm); minimal cross-reactivity |

| NF-κB Transgenic Mice | In vivo model for inflammation imaging | NF-κB-RE-luciferase transgenic mice | FVB background; responsive to inflammatory stimuli |

| IVIS Imaging System | In vivo bioluminescence detection | PerkinElmer IVIS Spectrum | Cooled CCD camera; sensitive photon detection |

| celltrackR Software | Immune cell migration analysis | celltrackR R package | Open-source; 2D/3D track analysis; quality control features |

| LPS | Toll-like receptor agonist for inflammation induction | Lipopolysaccharide from E. coli | Typical concentration 100 ng/mL for in vitro studies |

| Recombinant Cytokines | Immune cell activation | TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ | Concentration-dependent NF-κB activation |

| Methicillin | Methicillin, CAS:61-32-5, MF:C17H20N2O6S, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Metioprim | Metioprim, CAS:68902-57-8, MF:C14H18N4O2S, MW:306.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Emerging Imaging Technologies for Immunology Research

The field of immune imaging continues to evolve with several emerging technologies showing particular promise:

Multiplexed Bioluminescence Imaging: Simultaneous tracking of multiple biological processes using spectrally distinct luciferase reporters (e.g., FLuc and NLuc combination) enables more comprehensive understanding of immune responses. The key advantage lies in absent substrate cross-reactivity between these systems. Applications include monitoring CAR-T cell activity while simultaneously tracking tumor response, providing integrated assessment of immunotherapeutic efficacy [14].

Nanoparticle-Enhanced Imaging: Novel nanoparticle approaches are being developed to improve immune cell tracking precision. These systems facilitate monitoring of how immune cells target and attack cancer cells, particularly when combined with dendritic cell therapies that train the immune system to recognize cancer-specific antigens. Clinical trials are currently evaluating these approaches for boosting cancer immunotherapy [16].

Advanced Computational Analysis: New computational tools beyond celltrackR are emerging for deeper analysis of immune cell behavior. These include machine learning approaches for classifying cell migration patterns and predicting immune cell functions based on dynamic behavior. Integration with transcriptomic data (such as STAP-STP profiles) provides multidimensional insights into immune cell states [10] [17] [15].

Therapeutic Implications and Translational Applications

The methodologies described herein have significant implications for drug development and therapeutic assessment:

Cancer Therapeutics: NF-κB imaging enables evaluation of chemotherapeutic efficacy and resistance mechanisms. Since constitutive NF-κB activation blunts anticancer therapy effectiveness, these imaging approaches permit real-time assessment of NF-κB inhibitory compounds as potential chemosensitizers [8] [9].

Autoimmune Disease Monitoring: The capability to detect NF-κB activation before clinical symptom onset provides valuable opportunities for early therapeutic intervention in autoimmune conditions. This approach facilitates evaluation of anti-inflammatory drugs in preclinical models with enhanced translational potential [11].

Biomaterial Compatibility Screening: The noninvasive nature of NF-κB bioluminescence imaging allows efficient screening of biomaterial biocompatibility, accelerating development of medical implants and tissue engineering scaffolds with reduced inflammatory potential [12].

These advanced imaging and analysis protocols provide researchers with powerful tools for investigating inflammatory pathways, immune cell dynamics, and therapeutic interventions in longitudinal study designs that reduce animal usage while increasing data quality - aligning with the 3Rs principles of ethical animal research [13] [14].

In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) is a powerful optical imaging technique that has become indispensable for modern biological research, enabling the non-invasive interrogation of living animals using light emitted from luciferase-expressing bioreporter cells [18]. This technology has been applied to study a wide range of biomolecular functions including gene expression, drug discovery and development, cellular trafficking, protein-protein interactions, tumorigenesis, cancer treatment, and disease progression [18]. Unlike conventional methods that require euthanizing groups of animals at multiple time points, BLI allows investigators to perform longitudinal studies by repeatedly imaging the same cohort of animals over time [19]. This review will focus on the significant advantages of longitudinal BLI for inflammation research, with particular emphasis on how this approach reduces animal numbers while enabling powerful within-subject study designs that account for individual variation and provide more comprehensive data throughout the disease course.

The Principle of Longitudinal Bioluminescence Imaging

Longitudinal BLI involves the repeated monitoring of biological processes in the same living animal over time through the detection of light emitted from luciferase-expressing cells or tissues. The fundamental components of this technology include luciferase enzymes and their respective substrates. When luciferase-expressing cells are introduced into an animal model, either through injection of engineered cells or by using animals carrying a luciferase transgene, subsequent administration of the appropriate substrate enables the visual tracking of biological activities in real time [14].

A key advantage of BLI over fluorescence imaging is that it does not require an external light source for excitation, which results in minimal background autofluorescence and a much higher signal-to-noise ratio [14]. This characteristic is particularly valuable for longitudinal studies as it enables sensitive detection of biological processes even in deep tissues, though signal penetration remains challenging for blue-emitting luciferases [18] [1].

The longitudinal imaging process typically involves several key steps: animal preparation (including anesthesia and potentially fur removal), substrate administration (usually via intraperitoneal or intravenous injection), image acquisition using a sensitive charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, and quantitative analysis of the bioluminescent signal [13] [14]. This workflow can be repeated multiple times in the same animal, allowing researchers to track dynamic biological processes without the need to sacrifice multiple animal cohorts at different time points.

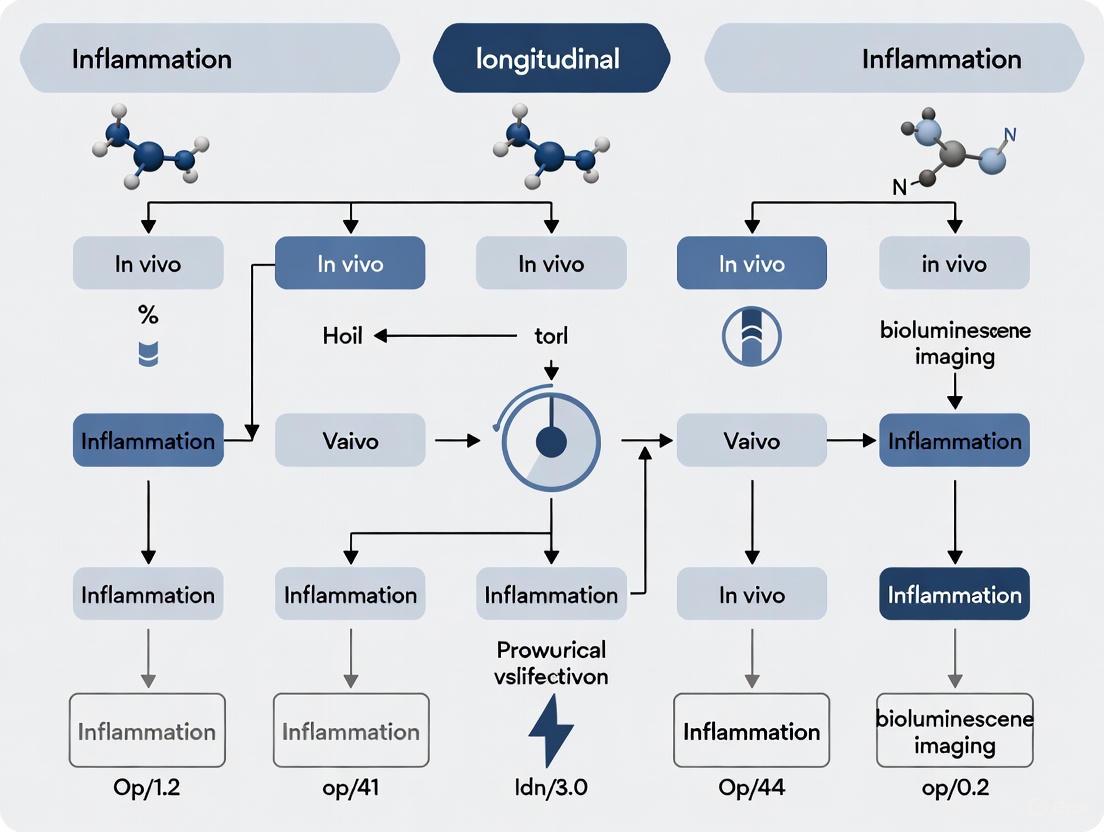

Figure 1: Workflow for longitudinal bioluminescence imaging studies. The same animals proceed through repeated imaging cycles, enabling within-subject monitoring of biological processes over time. IP = intraperitoneal; IV = intravenous; CCD = charge-coupled device.

Key Advantages of Longitudinal Imaging Designs

Reduction in Animal Numbers

Longitudinal BLI significantly reduces the number of animals required for well-powered experiments by enabling each subject to serve as its own control throughout the study duration. Traditional experimental designs necessitate separate animal cohorts for each time point, resulting in exponentially increasing animal requirements as more time points are added to the study [19]. In contrast, longitudinal imaging allows investigators to follow disease progression and therapeutic response in the same animals from baseline through peak response and resolution phases.

This approach directly aligns with the "3Rs" principle of animal research - Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement [14]. By reducing variability through within-subject comparisons and decreasing the total number of animals required, longitudinal BLI enhances both the ethical standards and statistical power of preclinical studies. The ability to monitor biological processes without euthanizing animals at intermediate time points has been particularly valuable in studies of dynamic processes such as inflammatory responses, where the timing of peak response may vary between individuals [13] [20].

Monitoring Dynamic Biological Processes

Longitudinal BLI provides unique insights into the temporal dynamics of disease progression and treatment response that would be impossible to capture with terminal endpoints. This capability is especially valuable in inflammation research, where immune responses evolve over time with distinct phases of activation, peak inflammation, and resolution.

In studies of uveitis, an inflammatory eye disease, researchers have successfully used longitudinal BLI to monitor intraocular inflammation in animal models over time. For example, one study demonstrated that bioluminescence signals in endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU) peaked at 18 hours post-induction and returned to near baseline levels by 48 hours, providing a quantitative measure of inflammatory dynamics that correlated with clinical observations [13]. Similarly, in primed mycobacterial uveitis (PMU) models, bioluminescence imaging detected significant increases in photon flux at peak inflammation (1.46 × 10^5 photons/second) compared to baseline (1.47 × 10^4 photons/second, P = 0.01) [13].

The ability to track these dynamic processes in individual animals allows researchers to identify unexpected patterns of disease progression or treatment response that might be missed when analyzing separate cohorts at predetermined time points [19]. This feature is particularly important for understanding complex inflammatory conditions where response timing may vary substantially between individuals.

Enhanced Data Quality Through Within-Subject Controls

Longitudinal imaging designs enhance data quality by using each animal as its own control, thereby reducing inter-animal variability and increasing statistical power. Traditional between-subject designs are confounded by inherent biological variation between individuals, requiring larger sample sizes to detect significant effects. In contrast, within-subject comparisons minimize this variability by tracking changes relative to baseline measurements in the same animal [18].

This advantage was demonstrated in a study of cell-type-specific inflammation in uveitis, where researchers generated transgenic mouse lines expressing luciferase in specific immune cell populations (myeloid cells, T cells, and B cells) [20]. By performing serial bioluminescence imaging for 35 days following uveitis induction, they were able to document distinct temporal patterns of immune cell infiltration: acute inflammation (day 2) was predominantly neutrophilic, followed by a T cell-dominated phase (day 7), and later B cell involvement (day 28 onward) [20]. This sophisticated characterization of immune dynamics would have been extremely challenging with terminal endpoints, requiring substantially more animals to achieve the same temporal resolution.

Quantitative Data from Longitudinal BLI Studies

Table 1: Representative quantitative data from longitudinal BLI studies in inflammation research

| Disease Model | Measurement Time Points | Baseline Signal (photons/sec) | Peak Signal (photons/sec) | Signal Return to Baseline | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primed Mycobacterial Uveitis (PMU) | Day 0, Day 2 | 1.47 × 10^4 | 1.46 × 10^5 (Day 2) | Not reported | [13] |

| Endotoxin-Induced Uveitis (EIU) | 0, 18, 48 hours | 1.09 × 10^4 | 3.18 × 10^4 (18 hours) | 48 hours | [13] |

| Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis (EAU) | Days 0, 15, 21 | Not reported | Nonsignificant increase | Not applicable | [13] |

| Myeloid Cell Inflammation (PMU model) | Weekly for 35 days | Baseline levels established on Day 0 | Significant increase on Day 2 | Return to baseline by Day 7 | [20] |

| T Cell Inflammation (PMU model) | Weekly for 35 days | Baseline levels established on Day 0 | Significant increase on Day 7 | Sustained through Day 35 | [20] |

| B Cell Inflammation (PMU model) | Weekly for 35 days | Baseline levels established on Day 0 | Significant increase starting Day 28 | Sustained through Day 35 | [20] |

Table 2: Comparison of bioluminescent reporters for longitudinal imaging

| Luciferase Reporter | Origin | Emission Peak | Substrate | Cofactors | Kinetics | Advantages for Longitudinal Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) | Photinus pyralis | 562 nm | D-luciferin | ATP, Mg²âº, Oâ‚‚ | Glow | Stable signal, optimal for longitudinal tracking [18] [21] |

| NanoLuc (NLuc) | Engineered | 460 nm | Furimazine | None | Glow | Small size, brightness, ATP-independent [14] |

| Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) | Renilla reniformis | 480 nm | Coelenterazine | Oâ‚‚ | Flash | Compatible with multiplexing [18] [14] |

| Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) | Gaussia princeps | 480 nm | Coelenterazine | None | Flash | Secreted nature allows detection in blood [22] [21] |

| Bacterial Luciferase (Lux) | Vibrio species | 490 nm | None (autonomous) | NADPH, Oâ‚‚ | Glow | No substrate injection required [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Longitudinal BLI in Inflammation Research

Animal Preparation and Uveitis Induction

This protocol is adapted from established models of uveitis [13] [20] and provides a framework for longitudinal BLI studies of ocular inflammation.

- Animals: C57BL/6 albino mice (6-8 weeks old, female)

- Uveitis Models:

- Primed Mycobacterial Uveitis (PMU): Subcutaneous injection of 100 μg killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra antigen in incomplete Freund's adjuvant, followed 7 days later by intravitreal injection of 3.5-5 μg Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen in 1 μL PBS into the right eye.

- Endotoxin-Induced Uveitis (EIU): Intravitreal injection of 1 μL of 125 ng/μL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in PBS into the right eye.

- Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis (EAU): Subcutaneous injection of 500 μg interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein peptide (IRBP1-20) in complete Freund's adjuvant on day 0, plus intraperitoneal pertussis toxin (0.15 μg) on days 0 and 2.

Bioluminescence Imaging Procedure

- Imaging System: PerkinElmer In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) Spectrum or equivalent

- Substrate Administration:

- Anesthesia: 2-3% isoflurane in oxygen throughout imaging procedure

- Image Acquisition:

- Field of view: "A"

- Subject height: 1.5 cm

- Binning: Medium

- Acquisition time: 1-5 minutes (optimize based on signal strength)

- Imaging time points: Baseline (before uveitis induction), then regularly throughout disease course (e.g., days 1, 2, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35)

- Image Analysis:

- Use Living Image software or equivalent

- Define regions of interest (ROIs) over inflamed eyes and background regions

- Quantify total flux (photons/second) for each ROI

- Subtract background signal from measured values

- Normalize to baseline measurements where appropriate

Validation Methods

- Clinical Scoring: Anterior chamber and posterior chamber inflammation scores according to established criteria [20]

- Optical Coherence Tomography: For objective assessment of ocular structural changes

- Histology: Post-mortem validation of inflammatory cell infiltration

- Flow Cytometry: Characterization of immune cell populations in inflamed tissues [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for longitudinal BLI studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Reporters | Firefly luciferase (FLuc), NanoLuc (NLuc), Renilla luciferase (RLuc) | Engineered into cells or animals to enable bioluminescence detection | Consider emission wavelength, kinetics, and substrate requirements for longitudinal studies [18] [14] |

| Luciferase Substrates | D-luciferin, Furimazine, Coelenterazine | Chemical reactants that generate light when processed by luciferase enzymes | Administration route (IP vs. IV) affects signal kinetics and intensity [14] [1] |

| Imaging Systems | IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer), other CCD-based systems | Detect and quantify bioluminescent signals from living animals | Cooled CCD cameras reduce thermal noise for sensitive detection [18] [13] |

| Animal Models | Transgenic reporter mice, cell line xenografts | Provide context for studying biological processes | Cell-type-specific reporters enable monitoring of specific immune populations [20] [19] |

| Anesthesia Equipment | Isoflurane delivery systems with nose cones | Maintain animal immobilization during imaging | Proper anesthesia is essential for image quality and animal welfare [13] |

| Analysis Software | Living Image Software, other quantification tools | Process and quantify bioluminescence image data | Enable background subtraction and signal quantification in defined ROIs [13] |

| Metoprine | Metoprine, CAS:7761-45-7, MF:C11H10Cl2N4, MW:269.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Metribuzin | Metribuzin Herbicide|Research Grade | Bench Chemicals |

Longitudinal bioluminescence imaging represents a transformative approach for inflammation research that simultaneously advances both scientific rigor and ethical standards in preclinical studies. By enabling researchers to track dynamic biological processes in the same animals over time, this technology reduces inter-animal variability, decreases the number of animals required for statistically powerful experiments, and provides unique insights into disease progression and treatment response that would be impossible to obtain through traditional terminal endpoints. As BLI technology continues to evolve with improvements in luciferase reporters, imaging equipment, and analytical methods, its application in longitudinal study designs will undoubtedly expand, further enhancing our understanding of inflammatory processes and accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) has emerged as a preeminent, non-invasive modality for longitudinal monitoring of biological processes in live animal models of disease and therapy development [1] [23]. This technology leverages the enzymatic reaction between luciferase enzymes and their substrates (luciferins) to produce visible light, enabling real-time visualization of everything from bacterial infection and inflammatory responses to the progression of chronic metabolic diseases [14] [24]. A core advantage of BLI is its capacity for longitudinal study design, allowing researchers to track disease pathogenesis or therapeutic response in the same cohort of animals over time, which enhances statistical power, reduces animal usage, and provides critical insights into dynamic biological timelines [13] [25]. This application note details key biological uses of BLI, supported by specific protocols and quantitative data, framed within the context of inflammation research.

Key Applications of In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging

Monitoring Inflammatory Responses in Uveitis Models

BLI enables direct, longitudinal quantification of intraocular inflammation, as demonstrated in studies of experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU), endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU), and primed mycobacterial uveitis (PMU) [13]. In these models, inflammation is detected via luminol, a substrate that emits light (λmax = 425 nm) upon oxidation by hypochlorous acid, a product of myeloperoxidase activity within activated neutrophils infiltrating the site [13]. This application provides a non-lethal, quantifiable alternative to terminal endpoints like histology.

Table 1: Bioluminescence Signal at Peak Inflammation in Mouse Uveitis Models

| Disease Model | Peak Bioluminescence (photons/second) | Baseline Bioluminescence (photons/second) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primed Mycobacterial Uveitis (PMU) | 1.46 x 10âµ | 1.47 x 10â´ | P = 0.01 |

| Endotoxin-Induced Uveitis (EIU) | 3.18 x 10â´ | 1.09 x 10â´ | P = 0.04 |

| Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis (EAU) | Non-significant increase | - | - |

Source: Data adapted from [13].

Key findings from these studies show that acute models with robust anterior inflammation (PMU and EIU) demonstrate significant changes in bioluminescence corresponding with peak inflammation, while the more indolent posterior uveitis of the EAU model generates a more modest signal [13]. The bioluminescence signal in EIU returned to near-baseline levels by 48 hours, highlighting the utility of BLI for tracking kinetic profiles [13].

Tracking Bacterial Infections and Antibiotic Efficacy

BLI is indispensable for studying bacterial pathogenesis and evaluating novel antimicrobial therapies in vivo. Research commonly employs engineered, bioluminescent bacteria (e.g., E. coli) to establish infections, allowing for real-time monitoring of bacterial load and spatial distribution without sacrificing the animal [25]. This approach was validated in a urinary tract infection (UTI) model, where the bioluminescent signal was strongly correlated with the bacterial burden determined by the traditional serial-plating method (colony-forming units, or CFU) [25].

Table 2: Correlation Between BLI Signal and Bacterial Burden

| Imaging Metric | Correlation with CFU | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Light Intensity | Semi-quantitative; affected by depth and tissue properties | Screening for antibiotic efficacy |

| 3D Tomographic Reconstruction (BLt) | Quantitative; enables calculation of CFU mmâ»Â³ in specific organs | Determining in vivo bacterial organ load and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies |

Source: Data adapted from [25].

Advanced tools like InVivoPLOT, which combines a body-conforming animal mold (BCAM) with bioluminescence tomography (BLt) and an organ probability map, now allow for fully automated, operator-independent quantification of bacterial density within deep-set organs like the kidneys [25].

Modeling Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes

In metabolic research, BLI is used to monitor dynamic processes such as pancreatic β-cell mass and function in models of Type 2 diabetes [24]. Transgenic mice, such as the MIP-Luc model, express firefly luciferase under the control of the mouse insulin promoter (MIP), restricting expression to pancreatic β-cells [24]. The bioluminescence signal intensity from the pancreatic region shows a strong positive correlation with β-cell mass, enabling non-invasive tracking of its expansion in response to a high-fat diet or its decline following streptozotocin (STZ)-induced ablation [24].

Interrogating Gene Regulation and Signaling Pathways

Reporter systems where luciferase expression is driven by specific promoter elements (e.g., NF-κB response elements) allow for the in vivo study of signal transduction and gene regulation [26] [1]. For instance, the effect of Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) on HIV-1 LTR-driven transcription was visualized in transgenic reporter mice, revealing organ-specific induction of the NF-κB pathway [26]. Similarly, the activity of specific promoters can be imaged to study processes like stem cell differentiation or the activity of cell signaling pathways in cancer [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Monitoring of Ocular Inflammation

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating uveitis in mouse models [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Luminol Sodium Salt | Chemiluminescent substrate for myeloperoxidase | Sigma Life Science; 200 mg/kg in PBS [13] |

| C57BL/6 Albino Mice | Animal model; absence of melanin reduces light absorption | Jackson Laboratories [13] |

| IVIS Spectrum Imager | Captures and quantifies bioluminescent signal | PerkinElmer [13] |

| Living Image Software | Analyzes total flux (photons/second) | PerkinElmer [13] |

| Inhaled Isoflurane | Anesthesia for animal immobilization during imaging | Veterinary grade [13] |

Methodology:

- Animal Preparation: Induce uveitis in C57BL/6 albino mice (e.g., for EIU, via intravitreal injection of 125 ng LPS). Use albino strains to minimize light absorption by pigment [13].

- Substrate Administration: Ten minutes before imaging, administer an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of luminol sodium salt at a dose of 200 mg/kg [13].

- Anesthesia and Positioning: Anesthetize the animal with inhaled isoflurane. Dilate eyes with topical phenylephrine (2.5%) and apply a lubricating ophthalmic gel to prevent corneal drying. Position the animal in lateral decubitus with the ocular surface directly facing the camera sensor [13].

- Image Acquisition: Capture images using an IVIS Spectrum system with field of view "A," subject height of 1.5 cm, and medium binning. Acquire a sequence of 5-minute images starting 10 minutes post-luminol injection [13].

- Data Analysis: Using Living Image software, define a region of interest (ROI) around the eye. Quantify the signal as total flux (photons/second) and subtract background signal from a reference ROI. Compare longitudinal data to baseline (day 0) measurements [13].

Protocol 2: Firefly Luciferase-Based Tumor Cell Imaging

This is a standard protocol for monitoring tumor growth and metastasis using firefly luciferase-expressing cells [23] [14] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| D-Luciferin, K⺠Salt | Substrate for Firefly luciferase | Promega VivoGlo; 150 mg/kg in PBS [14] [27] |

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) Cells | Reporter cells for tumor burden | Stable expression via lentiviral transduction [23] |

| CCD Camera System | Detects low-light bioluminescence | Cooled CCD camera (e.g., IVIS) [23] [14] |

| Insulin Syringe | For precise substrate injection | Lo-dose B-D 1/2 cc 28G1/2 [23] |

Methodology:

- Cell Implantation: Implant firefly luciferase-expressing tumor cells (e.g., via subcutaneous or orthotopic injection) into immunocompromised or syngeneic mice [23].

- Substrate Administration: Inject D-luciferin intraperitoneally at a standard dose of 150 mg/kg. The IP route is preferred for its ease and signal stability, with peak emission occurring approximately 10 minutes post-injection [14] [27].

- Image Acquisition: Anesthetize mice with isoflurane. Acquire images 10-15 minutes after D-luciferin injection. Use auto-exposure settings or a series of exposures (e.g., 5 seconds to 5 minutes) to ensure signals are within the camera's linear range without saturation [27].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the tumor burden by measuring the total flux (photons/second) within an ROI drawn over the tumor signal. For longitudinal studies, image animals from the same position and at a consistent time after substrate injection to ensure comparability [23] [27].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Endotoxin-Induced NF-κB Activation Pathway

Diagram Title: Endotoxin-Induced NF-κB Activation Pathway

Longitudinal BLI Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Longitudinal BLI Experimental Workflow

In the field of longitudinal in vivo imaging for inflammation research, selecting the appropriate optical imaging technique is paramount for data accuracy and experimental success. This application note provides a detailed comparison between fluorescence imaging and bioluminescence imaging (BLI), focusing on two critical parameters: signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and tissue penetration depth. For researchers tracking inflammatory processes over time, understanding these fundamental differences ensures reliable data collection and interpretation in studies involving animal models of disease, drug efficacy testing, and mechanistic investigations.

Technical Comparison: SNR and Penetration Depth

Fundamental Mechanisms and Their Implications

The core distinction between these modalities lies in their physical mechanisms for light generation, which directly influences their performance.

Fluorescence Imaging requires an external light source to excite fluorescent molecules (fluorophores). The emitted light is then detected to form an image. A significant challenge is that the excitation light can be scattered and absorbed by tissues, and it can also cause autofluorescence from endogenous molecules, generating a substantial background signal that reduces the SNR [28] [14]. Furthermore, the excitation light itself is subject to tissue absorption and scattering, which limits the effective penetration depth [29].

Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) is an auto-illuminating process. It relies on luciferase enzymes (e.g., firefly luciferase) oxidizing a substrate (e.g., D-luciferin). This biochemical reaction produces visible light without the need for external excitation. The absence of exciting light virtually eliminates issues related to autofluorescence and light scattering, resulting in a very high SNR [14]. This makes BLI exceptionally sensitive for detecting low numbers of cells or weak biological signals deep within an animal.

The table below synthesizes key performance characteristics based on current literature and reagent specifications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Fluorescence and Bioluminescence Imaging

| Feature | Fluorescence Imaging | Bioluminescence Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Background Signal | High (due to tissue autofluorescence under external light) [28] | Extremely low (no external excitation, minimal tissue autofluorescence) [14] |

| Typical SNR | Lower; can be enhanced by advanced algorithms (e.g., ~8% increase with lock-in processing) [30] | Inherently very high |

| Penetration Depth | Limited by scattering/absorption of excitation and emission light | Superior for deep-tissue imaging; limited primarily by emission light absorption |

| Key Reporter | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), FITC, others | Firefly Luciferase (FLuc), NanoLuc (NLuc) |

| Emission Peak | Varies by fluorophore (e.g., ~515 nm for FITC) [28] | FLuc: ~562 nm [14]; NLuc: ~460 nm [14] |

| Optimal Wavelength | >600 nm for better penetration | >600 nm for better penetration [14] |

| Substrate/Kinetics | N/A | D-luciferin (for FLuc); time-to-peak and signal duration depend on dose and route [31] |

Table 2: Bioluminescence Reporter Systems

| Reporter | Substrate | Emission Peak | Key Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) | D-luciferin | 562 nm [14] | ATP-dependent, yellow-green light, many pre-engineered cell lines [14] | Tracking tumor progression, ATP-dependent processes [14] |

| NanoLuc (NLuc) | Furimazine (FFz) | 460 nm [14] | Small size (19 kDa), very bright, ATP-independent, short exposure times [14] | Viral reporters, protein fusions, tracking exosomes [14] |

| Akaluc/AkaLumine | AkaLumine | Red-shifted [14] | Engineered FLuc variant for better tissue penetration and higher signal [14] | Deep-tissue imaging where signal intensity is critical [14] |

| Click Beetle Luciferase | D-luciferin | Red (~615 nm) [29] | Naturally red-shifted emission | Enhanced tissue penetration [29] |

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting between fluorescence and bioluminescence imaging for longitudinal inflammation studies.

Optimized Protocol for Longitudinal BLI of Inflammation

This protocol is optimized for sensitivity and reproducibility in monitoring inflammatory processes in the brain, based on the work by Aswendt et al. [31], and can be adapted for other tissues.

Reagent and Material Preparation

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| D-Luciferin | Potassium salt, in vivo grade (e.g., VivoGlo) [14] | Substrate for firefly luciferase (FLuc); oxidized to produce light. |

| Luciferase-Expressing Cells | Stable transfection or transgenic animal (e.g., DCX-Luc mice) [31] | Biological source of the luciferase reporter enzyme. |

| Anesthetic | Isoflurane (e.g., 3% for induction, 1.5-2% for maintenance) [31] | Ensures animal immobility during image acquisition. |

| Sterile PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 | Vehicle for dissolving D-Luciferin substrate. |

| Depilatory Cream | Commercial hair removal cream | Removes fur from the imaging area to minimize light absorption and scattering. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Substrate Injection:

- Prepare a stock solution of D-Luciferin at a concentration of 30 mg/mL in sterile PBS.

- Inject D-Luciferin intraperitoneally (IP) at a dose of 300 mg/kg body weight [31]. Note: Intravenous (IV) injection provides a faster and brighter initial signal but decays rapidly and is more technically challenging [14] [31].

- The higher dose of 300 mg/kg has been shown to provide a significant signal gain (~200%) compared to the standard 150 mg/kg dose for brain imaging, without reaching saturation [31].

Anesthesia Induction:

- Wait for 5 minutes post-injection. This is a critical step, as injecting the substrate before anesthesia induction leads to significantly higher and more stable bioluminescence signals [31].

- After the 5-minute wait, induce anesthesia with 3% Isoflurane in an induction chamber.

Animal Preparation:

- Transfer the animal to the imaging chamber, maintaining anesthesia with 1.5-2% Isoflurane delivered via a nose cone.

- Apply depilatory cream to the skin over the region of interest (e.g., the head for brain imaging). Leave it on for about 1 minute, then gently wipe it off and clean the area with a damp paper towel to ensure no residue remains. This step drastically improves light transmission.

Image Acquisition:

- Position the animal in the bioluminescence imager (equipped with a cooled CCD camera) in a supine or lateral position, depending on the target tissue.

- Begin image acquisition 10-15 minutes after the D-Luciferin injection, as this is typically when the signal peaks for IP administration [31]. Acquire a series of images with exposure times ranging from 1 second to 5 minutes to ensure the signal is within the dynamic range of the camera and not saturated.

- Maintain a constant temperature on the imaging stage (e.g., 37°C) to ensure animal welfare and stable physiological conditions.

Diagram 2: Step-by-step workflow for the optimized in vivo BLI protocol.

Data Analysis and SNR Calculation

- Regions of Interest (ROI): Draw an ROI around the signal source (e.g., the brain) and an identical ROI over a background region (e.g., the shoulder or an area with no expected signal).

- Quantification: Use the imaging software to calculate the total flux (photons/second) or average radiance (p/s/cm²/sr) within each ROI.

- SNR Calculation: Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio using the formula: ( SNR = \frac{\text{Mean Signal}{\text{ROI}} - \text{Mean Background}{\text{ROI}}}{\text{Standard Deviation}_{\text{Background}}} ) This optimized protocol has been demonstrated to lower the detection limit from 6,000 to 3,000 luciferase-expressing cells grafted in the mouse brain, directly due to a gain in the SNR [31].

Advanced SNR Enhancement Techniques for Fluorescence Imaging

For experimental scenarios where fluorescence imaging is necessary (e.g., for high temporal resolution or multiplexing), several advanced techniques can be employed to mitigate its inherent SNR limitations.

- Digital Lock-In Algorithm: This method modulates the light sources (e.g., white and near-infrared) at specific frequencies. The acquired images are then demodulated to separate the signal from the background noise. This technique has been shown to increase the SNR of white light and fluorescent images by 8.2% and 6.7%, respectively, in a fluorescence endoscope system [30].

- Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) and Substrate Optimization: Using microfluidic chips fabricated on silicon-on-insulator (SOI) substrates instead of conventional silicon wafers creates an ultra-flat surface. This minimizes light scattering and angle-dependent filter issues, reducing the fluorescent background signal by ~5 times and improving the SNR for single-molecule detection by more than 18 times [28].

- Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM): FLIM uses the characteristic time a fluorophore remains in its excited state (lifetime) to generate contrast, rather than relying solely on intensity. This lifetime is independent of fluorophore concentration and probe intensity, making it highly sensitive to the molecular microenvironment (e.g., pH, ion concentration) and immune to many artifacts that plague intensity-based measurements. It is particularly powerful when combined with Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) to study protein-protein interactions [32] [33] [34].

The choice between bioluminescence and fluorescence imaging for longitudinal inflammation studies involves a direct trade-off between sensitivity and versatility.

- Bioluminescence Imaging is the superior choice for quantitative, high-sensitivity tracking of specific cell populations or molecular pathways over time in live animals, especially when targets are located in deep tissues. Its inherently low background provides an excellent SNR, which is critical for reliable longitudinal monitoring.

- Fluorescence Imaging is indispensable for studies requiring real-time kinetics, high spatial resolution, or the simultaneous monitoring of multiple targets (multiplexing). While its SNR is generally lower, advanced techniques like FLIM and lock-in processing can significantly enhance its performance.

The optimized BLI protocol outlined here, featuring a higher D-Luciferin dose (300 mg/kg) and pre-anesthesia injection, provides a robust methodological framework for maximizing data quality in preclinical inflammation research and drug development.

Practical Implementation: BLI Protocols for Specific Inflammatory Conditions and Disease Models

Non-invasive bioluminescence imaging (BLI) enables longitudinal assessment of inflammation in live animal models. This application note details the use of two chemiluminescent probes—luminol and lucigenin—to distinguish between acute and chronic inflammatory phases by detecting distinct oxidative burst activities in neutrophils and macrophages. Luminol bioluminescence specifically detects myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity during neutrophil-mediated acute inflammation, whereas lucigenin bioluminescence relies on phagocyte NADPH oxidase (Phox) activity in macrophages during chronic phases. We provide validated protocols, quantitative data, and mechanistic insights to support the application of these probes in preclinical research.

Inflammation is a fundamental biological response involved in a wide range of pathological conditions, including microbial infection, wound healing, diabetes, cancer, and autoimmune diseases [35]. The inflammatory process requires coordinated recruitment and activation of various immune cells, primarily neutrophils in the acute phase and macrophages in the chronic phase [36] [35]. Non-invasive imaging methods that can distinguish between these cellular phases provide powerful tools for quantitative longitudinal assessment of disease progression and therapeutic intervention.

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) with chemiluminescent substrates enables real-time, non-invasive visualization of specific biological processes in live animals. Luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) and lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium nitrate) are two well-characterized probes that react with distinct reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by different phagocyte populations [36] [35]. This technical note details the underlying mechanisms, optimized protocols, and applications of these probes for distinguishing neutrophil-dominated acute inflammation from macrophage-dominated chronic inflammation in vivo.

Background and Mechanisms

The Phagocytic Oxidative Burst in Inflammation

Phagocyte NADPH oxidase (Phox) is the primary source of superoxide production in both neutrophils and macrophages [35]. During phagocytosis, neutrophils assemble the Phox holoenzyme at phagosomal membranes, where it consumes oxygen to produce superoxide anion in a rapid burst known as the "respiratory burst" [35]. The biochemical environment and subsequent reactive oxygen species differ significantly between neutrophil and macrophage phagocytes:

- Neutrophils: Contain high levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO), which constitutes approximately 5% of neutrophil dry weight [37]. MPO catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to highly bactericidal hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [37] [35].

- Macrophages: Have lower MPO expression and assemble Phox primarily at the plasma membrane rather than in phagosomes, producing superoxide at lower levels for regulatory functions [35].

Probe Specificity and Mechanisms

Table 1: Comparison of Luminol and Lucigenin Specificity

| Parameter | Luminol | Lucigenin |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cellular Target | Neutrophils | Macrophages |

| Key Enzymatic Requirement | Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Phagocyte NADPH Oxidase (Phox) |

| Reactive Species Detected | Hypochlorous acid (HOCl), other MPO-derived oxidants | Superoxide anion (O₂•â») |

| Specificity Evidence | Abolished in MPO-deficient mice despite neutrophil infiltration [37] | Dependent on Phox activity; independent of MPO [36] |

| Optimal Imaging Window | 5-25 minutes post-injection [37] [13] | 1-15 minutes post-injection [35] |

Figure 1: Mechanism of Luminol and Lucigenin Specificity for Neutrophils and Macrophages

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Inflammation Imaging

| Reagent | Composition/Preparation | Storage | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol Sodium Salt | 10 mg/ml in sterile normal saline (0.9% NaCl) [35] | -20°C | MPO-dependent detection of neutrophil activity |

| Lucigenin | 2.5 mg/ml in sterile normal saline [35] | -20°C | Phox-dependent detection of macrophage activity |

| PMA (Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) | 5 mg/ml in DMSO, dilute to 1 mg/ml in PBS before use [35] | -20°C | Potent protein kinase C activator for phagocyte stimulation |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | 1 mg/ml in sterile PBS [35] | -20°C | Toll-like receptor agonist for inflammation induction |

| 4-ABAH (4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide) | 0-500 μM in appropriate buffer [37] | -20°C | Selective MPO inhibitor for specificity controls |

Signal Characteristics and Detection Parameters

Table 3: Quantitative Imaging Parameters for Inflammation Probes

| Parameter | Luminol | Lucigenin |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Dosage | 100-200 mg/kg [13] [35] | 10-25 mg/kg [35] |

| Signal Peak Time | 20-25 minutes post-stimulation [37] | Within 15 minutes post-injection [35] |

| Signal Intensity Range | 30-40-fold over background [37] | Model-dependent |

| Sensitivity | <5 × 10³ phagocytes in 1 μl whole blood [37] | Model-dependent |

| Inhibition IC₅₀ | 4-ABAH: 1.0 ± 0.7 μM (purified MPO), 50 ± 15 μM (whole blood) [37] | Phox inhibitor-dependent |

Application Across Disease Models

Table 4: Probe Performance in Preclinical Inflammation Models

| Disease Model | Luminol Signal | Lucigenin Signal | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Dermatitis | Significant increase at peak inflammation [37] | Not reported | Luminol bioluminescence colocalized with histological inflammation sites [37] |

| Focal Arthritis | Significant increase at peak inflammation [37] | Not reported | MPO-dependent signal abolished in Mpo−/− mice [37] |

| Endotoxin-induced Uveitis (EIU) | 3.18 × 10ⴠp/s at peak vs 1.09 × 10ⴠp/s baseline (P = 0.04) [13] | Not reported | Signal returned to baseline by 48 hours [13] |

| Subcutaneous PMA | Robust acute signal [35] | Limited acute signal [35] | Distinction between acute (luminol) and chronic (lucigenin) phases |

| Subcutaneous LPS | Early acute signal [35] | Sustained chronic signal [35] | Temporal transition from neutrophil to macrophage dominance |

Experimental Protocols

Subcutaneous Inflammation Models

PMA-Induced Inflammation

Figure 2: PMA-Induced Inflammation Model Workflow

PMA Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solution at 5 mg/ml in DMSO. Store at -20°C. Before inoculation, thaw and dilute to 1 mg/ml in PBS [35].

Animal Preparation: Anesthetize mice in an induction chamber with 1-2% isoflurane. Confirm general anesthesia by loss of movement and constant respiratory rate [35].

Injection Procedure:

- Clean and disinfect injection site on left flank with isopropyl alcohol wipe

- Using sterile technique, inject 50 μl of PMA inoculation solution (containing 50 μg of PMA) into subcutaneous space

- Remove excess fluid with isopropyl alcohol pad

- Avoid analgesia as it may affect inflammatory responses [35]

Post-Injection Care:

- Return animal to housing cage and monitor recovery from anesthesia

- Use heating pad to maintain body temperature during recovery [35]

LPS-Induced Inflammation

LPS Solution Preparation: Dissolve lipopolysaccharide (LPS from Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis) in sterile PBS at 1 mg/ml prior to subcutaneous inoculation [35].

Footpad Injection:

- Anesthetize C57BL/6J mice with 1-2% isoflurane

- Clean injection site on left footpad with isopropyl alcohol wipe

- Inject 50 μl of LPS solution (containing 50 μg of LPS) into left footpad

- Remove excess fluid from injection site [35]

Bioluminescence Imaging Protocol

Substrate Administration:

- Anesthetize animal with 1-2% isoflurane

- Intraperitoneally inject either:

- Luminol solution (10 mg/ml, final dosage 100 mg/kg) for acute inflammation imaging, OR

- Lucigenin solution (2.5 mg/ml, final dosage 25 mg/kg) for chronic inflammation imaging [35]

- Note: C57BL/6J strain has lower lucigenin tolerability; consider lower dose (10-15 mg/kg) to avoid toxicity [35]

Imaging Parameters:

- Transfer animal to imaging chamber of bioluminescence imaging system

- Perform sequential imaging at 1 min intervals

- Each imaging step: 1 min acquisition time, f/stop = 1, binning = 16, 0 sec delay

- Program 15 one-minute steps to determine maximal luminescence output [35]

Post-Processing and Analysis:

- Use imaging software to calculate peak total bioluminescent signal through standardized regions of interest (ROI)

- Present images as radiance in photons/sec/cm²/sr with minimal and maximal threshold indicated

- Quantitative data presented as total flux in photons per second per ROI [35]

Specificity Controls and Validation

MPO Inhibition:

- Use 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABAH) at concentrations of 0-500 μM to inhibit MPO activity [37]

- Confirm MPO-dependence with significant signal reduction

Genetic Controls:

- Utilize Mpo−/− mice to verify luminol specificity [37]

- Compare wild-type and knockout responses to confirm MPO-dependent signaling

Cellular Infiltration Validation:

Applications in Disease Models

The luminol/lucigenin imaging approach has been successfully applied across multiple disease models, demonstrating its versatility for inflammatory process assessment:

Ocular Inflammation Models

In endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU), luminol bioluminescence significantly increased at peak inflammation (3.18 × 10ⴠp/s) compared to baseline (1.09 × 10ⴠp/s, P = 0.04), returning to near baseline levels by 48 hours [13]. This rapid kinetics aligns with neutrophil infiltration patterns in acute ocular inflammation.

Longitudinal Monitoring of Inflammation Phases

The combination of luminol and lucigenin enables non-invasive tracking of inflammatory phase transitions. In subcutaneous inflammation models, luminol detects early neutrophil activity (0-48 hours), while lucigenin identifies subsequent macrophage activity (48+ hours), allowing complete longitudinal assessment without sacrificing animals [36] [35].

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Optimize substrate dosage and imaging timing. Luminol typically peaks 20-25 minutes post-stimulation [37]

- Probe Toxicity: Monitor animals for respiratory distress, particularly with lucigenin in C57BL/6J mice [35]

- Signal Specificity: Always include appropriate controls (MPO inhibitors, genetic controls) to verify signal specificity [37]

- Background Signal: Distinguish true inflammatory signal from background by careful ROI selection and background subtraction [13] [20]

The combination of luminol and lucigenin bioluminescence imaging provides researchers with a powerful methodology for non-invasive distinction between acute neutrophil-dominated and chronic macrophage-dominated inflammation. The specific protocols and quantitative data presented herein enable robust application across preclinical models, facilitating longitudinal assessment of inflammatory progression and therapeutic efficacy in live animals.

NF-κB Activation Monitoring in Pulmonary Inflammation Models Using Transgenic Reporter Mice

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a pivotal transcription factor that regulates inflammatory responses and is a major pathogenic feature of various inflammatory diseases, including acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [38] [39]. Monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of NF-κB activation in live animal models is crucial for understanding inflammatory pathogenesis and evaluating anti-inflammatory therapies. Transgenic reporter mice enable non-invasive, longitudinal monitoring of NF-κB activity, providing insights into complex inflammatory processes in pulmonary inflammation models that traditional endpoint measurements cannot capture [38] [40].

This application note details the use of cutting-edge transgenic reporter mice and optimized protocols for monitoring NF-κB activation in preclinical models of pulmonary inflammation, with a focus on LPS-induced lung injury.

Reporter Mouse Models for NF-κB Imaging

The selection of an appropriate reporter mouse model is fundamental to the success of in vivo NF-κB imaging studies. The table below compares the key reporter systems available.

Table 1: Key Features of NF-κB Reporter Mouse Models

| Reporter Model | Detection Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB-Luc (Bioluminescence) [38] | Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) | Expresses luciferase under NF-κB response elements. | Non-invasive, suitable for longitudinal whole-body imaging, high signal-to-noise ratio. | Limited spatial resolution; substrate pharmacokinetics can influence signal. |

| Fluorescent Knockin (e.g., mEGFP-RelA, mScarlet-c-Rel) [40] | Fluorescence Imaging (Flow Cytometry, Microscopy) | Endogenous loci of RelA or c-Rel tagged with fluorescent proteins (e.g., mEGFP, mScarlet). | Single-cell resolution, accurate endogenous expression, enables dynamic live-cell imaging, no substrate needed. | Requires tissue extraction for high-resolution analysis (except intravital imaging). |