Macrophage Polarization in Chronic Inflammation: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms governing macrophage polarization and its pivotal role in chronic inflammatory diseases.

Macrophage Polarization in Chronic Inflammation: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms governing macrophage polarization and its pivotal role in chronic inflammatory diseases. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on the M1/M2 spectrum, key signaling pathways (JAK/STAT, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt), and immunometabolic reprogramming. The content explores cutting-edge methodological approaches for modulating polarization, including natural compounds, nanomaterials, and repurposed drugs, with applications in oncology, autoimmune disorders, and metabolic diseases. It further addresses challenges in therapeutic targeting and offers comparative validation of strategies across disease contexts, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on translating mechanistic insights into novel clinical interventions for restoring immune homeostasis.

Decoding the Macrophage Polarization Spectrum: From Basic Biology to Inflammatory Dysregulation

Macrophages, pivotal cells of the innate immune system, exhibit remarkable functional plasticity, allowing them to respond dynamically to microenvironmental cues [1]. This plasticity is exemplified by their ability to polarize into distinct functional phenotypes, a process critical for orchestrating immune responses in health and disease [2]. The M1/M2 paradigm provides a foundational framework for understanding these polarization states, mirroring the Th1/Th2 nomenclature of T helper cells [3]. Classically activated M1 macrophages typically initiate and sustain pro-inflammatory responses, while alternatively activated M2 macrophages promote immunoregulation, tissue repair, and resolution of inflammation [4] [1]. Although this classification represents a simplified continuum of activation states rather than discrete entities, it remains an essential utilitarian shorthand for discussing the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory extremes of macrophage function [4]. In chronic inflammatory diseases such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and tumor microenvironments, the balance between M1 and M2 polarization significantly influences disease progression, making understanding of this paradigm therapeutically relevant [5] [2].

Historical Foundation and Conceptual Evolution

The conceptual foundation of macrophage polarization emerged from parallel investigations in immunology during the late 20th century. In 1986, Mosmann and colleagues established the Th1/Th2 dichotomy for T helper cells, which provided the conceptual groundwork for analogous macrophage categorization [3]. The term "macrophage activation" was introduced earlier by Mackaness in the 1960s within infection contexts, describing antigen-dependent enhancement of microbicidal activity against intracellular pathogens [3]. Subsequent research revealed that Th1-derived interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) promoted this classical activation, while Th2 cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13 induced a different activation pattern characterized by high endocytic activity and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, termed "alternative activation" by Stein, Doyle, and colleagues [3].

The specific M1/M2 terminology originated from investigations of macrophage arginine metabolism by Mills and colleagues, who observed that macrophages from mouse strains with Th1 and Th2 backgrounds metabolized arginine through divergent pathways—M1 macrophages produced toxic nitric oxide (NO), while M2 macrophages produced trophic polyamines [3]. Mantovani and colleagues later expanded this classification, grouping polarization stimuli into a continuum between two polarized states: M1 (induced by IFN-γ combined with LPS or TNF) and M2 (with subgroups M2a induced by IL-4, M2b induced by immune complexes, and M2c induced by IL-10 or glucocorticoids) [3]. This categorization acknowledged the diversity of macrophage activation while providing a structured framework for investigation.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in M1/M2 Paradigm Development

| Year | Key Discovery | Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Concept of "macrophage activation" | Mackaness | Described enhanced microbicidal activity against intracellular pathogens |

| 1986 | Th1/Th2 dichotomy | Mosmann et al. | Established functional T helper cell subsets providing conceptual basis for macrophage polarization |

| 1990s | Alternative activation | Stein, Doyle et al. | Defined IL-4/IL-13-induced activation state with distinct receptor expression and cytokine profile |

| 2000 | M1/M2 terminology | Mills et al. | Introduced M1/M2 classification based on arginine metabolism pathways in different mouse strains |

| Early 2000s | Expanded polarization states | Mantovani et al. | Categorized M2 subgroups (M2a, M2b, M2c) based on different inducing stimuli |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

M1 Polarization Signaling Cascades

Classical M1 macrophage polarization is primarily triggered by IFN-γ alone or in combination with microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [1]. The binding of IFN-γ to its receptor (IFNGR) activates Janus kinase (JAK) adapters, leading to phosphorylation and activation of signal transducer and transcription activator 1 (STAT1) [1]. Activated STAT1 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it induces expression of pro-inflammatory genes including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II, IL-12, and NOS2 [1].

Simultaneously, LPS recognition by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activates two distinct signaling adapters: TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) and myeloid differentiation response 88 (MyD88) [1]. The TRIF-dependent pathway activates interferon-responsive factor 3 (IRF3), driving type I interferon production, while MyD88 signaling activates nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) via MAPK pathways [1]. These transcription factors collectively promote expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1β, IL-12), chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL11), co-stimulatory molecules, and antigen-processing proteins that characterize the M1 phenotype [1].

M2 Polarization Signaling Cascades

Alternative M2 macrophage polarization is primarily induced by IL-4 and IL-13, which signal through the IL-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Rα) chain [1]. Receptor engagement activates JAK1 and JAK3, leading to phosphorylation and activation of STAT6 [1]. Activated STAT6 translocates to the nucleus and cooperates with other transcription factors including IRF4 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) to drive expression of characteristic M2 markers [6] [1]. These include arginase 1 (Arg1), chitinase-like proteins (Ym1), resistin-like-α (Fizz1), CCL17, and the macrophage mannose receptor (CD206) [1].

IL-10 represents another potent M2-inducing cytokine that signals through its receptor (IL10R), leading to activation of STAT3 [1]. STAT3 induces expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), which inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling pathways, thereby reinforcing the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [1]. Glucocorticoids also promote M2 polarization through binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GR), which translocate to the nucleus and either directly bind DNA to transcribe anti-inflammatory genes like IL-10 or interact with transcription factors like NF-κB to inhibit inflammatory gene expression [1].

Table 2: Key Transcription Factors in Macrophage Polarization

| Transcription Factor | Primary Inducers | Target Genes | Polarization Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | IFN-γ, IFN-α/β | MHC II, IL-12, NOS2, SOCS1 | Master regulator of M1 polarization |

| NF-κB | LPS (via TLR4/MyD88), TNF-α | TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, CXCL chemokines | Drives pro-inflammatory gene expression |

| STAT6 | IL-4, IL-13 (via IL-4Rα) | Arg1, Ym1, Fizz1, CCL17, CD206 | Master regulator of IL-4-induced M2 polarization |

| PPARγ | IL-4, fatty acids | Arg1, CD36, FABP4 | Enhances M2 gene expression and metabolic reprogramming |

| STAT3 | IL-10 | SOCS3, IL-10, IL1-R2 | Promotes anti-inflammatory M2 polarization |

| IRF4 | IL-4, IL-13 | CCL17, CCL22, CD206 | Cooperates with STAT6 for M2 gene expression |

Metabolic Reprogramming in Polarized Macrophages

Distinct Metabolic Signatures

M1 and M2 macrophages exhibit fundamentally different metabolic programs that support their divergent functions [6]. M1 polarization is characterized by a shift toward glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and fatty acid synthesis, even under normoxic conditions [6] [7]. This metabolic reprogramming is driven by stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1α), which promotes expression of glycolytic enzymes and pro-inflammatory genes [7]. The glycolytic shift provides rapid ATP generation and generates metabolic intermediates that support inflammatory functions, while also producing lactate which can itself exert immunomodulatory effects [6].

In contrast, M2 macrophages primarily utilize oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) for energy production [6] [7]. This metabolic phenotype supports the longevity and tissue remodeling functions of M2 macrophages. IL-4 signaling promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and enhances electron transport chain activity, making M2 macrophages dependent on intact tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle function [7]. Additionally, M2 polarization increases dependence on fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, with PPARγ playing a key role in regulating these metabolic pathways [6].

Advanced Metabolic Imaging Techniques

Recent advances in metabolic imaging have enabled non-invasive classification of macrophage polarization states. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) of the intrinsic fluorophores NAD(P)H and FAD+ provides quantitative metrics of cellular metabolic states [7]. NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetime parameters differ between M1 and M2 macrophages due to their distinct metabolic programs: M1 macrophages exhibit FLIM signatures consistent with enhanced glycolysis, while M2 macrophages show parameters indicative of active oxidative phosphorylation [7].

When combined with machine learning algorithms such as random forests, 2P-FLIM can classify human macrophage polarization with excellent accuracy (ROC-AUC value of 0.944) based on metabolic parameters [7]. This non-destructive methodology enables temporal monitoring of polarization states and responses to therapeutic interventions without requiring fixation or staining, making it particularly valuable for dynamic studies of macrophage plasticity in chronic inflammation [7].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Established Polarization Protocols

In vitro polarization of human macrophages typically begins with isolation of monocytes from peripheral blood or utilization of monocytic cell lines like THP-1 [6] [7]. THP-1 cells are differentiated into macrophages (M0) using phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 24 hours, followed by polarization induction [6]. For M1 polarization, cells are treated with IFN-γ (typically 20-100 ng/mL) combined with LPS (10-100 ng/mL) for 24 hours to 4 days to achieve full polarization [6]. For M2 polarization, IL-4 (10-20 ng/mL) is administered for the same duration [6]. Similar protocols apply to primary human monocyte-derived macrophages, which are generated by culturing CD14+ monocytes with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) for 5-7 days before polarization induction.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Macrophage Polarization Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Typical Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 Inducers | IFN-γ, LPS (from E. coli or Salmonella), TNF-α | Activate classical M1 polarization signaling pathways | IFN-γ: 20-100 ng/mL; LPS: 10-100 ng/mL |

| M2 Inducers | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, M-CSF, glucocorticoids | Promote alternative M2 polarization | IL-4: 10-20 ng/mL; IL-13: 10-20 ng/mL; IL-10: 10-50 ng/mL |

| Signaling Inhibitors | MEK inhibitors (e.g., U0126, trametinib), HDAC inhibitors, PI3K inhibitors | Block specific polarization pathways for mechanistic studies | Varies by inhibitor potency and specificity |

| Metabolic Probes | 2-NBDG (glucose analog), MitoTracker, NAAD(P)H FLIM | Assess metabolic reprogramming during polarization | Manufacturer recommended concentrations |

| Polarization Markers | Antibodies against CD86, CD80, MHC II (M1); CD206, CD163, Arg1 (M2) | Identify and validate polarization states by flow cytometry or immunofluorescence | Manufacturer recommended dilutions |

Validation and Characterization Methods

Comprehensive characterization of polarized macrophages requires multimodal assessment of surface markers, cytokine secretion, gene expression, and metabolic profiles. Well-established M1 markers include surface proteins CD80, CD86, and MHC II; cytokines IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-1β; and enzymes iNOS (NOS2) [6] [1]. Prototypical M2 markers include surface receptors CD206 (mannose receptor), CD163, and CD209; cytokines IL-10, TGF-β, and CCL17; and enzymes Arg1, Ym1/2, and Fizz1 [6] [1].

Global quantitative proteomic analyses have identified approximately 7,900 proteins differentially expressed between M1 and M2 macrophages, with M2 macrophages showing upregulated MRC1, TGM2, FABP4, CCL24, and CCL26, while M1 macrophages express high levels of IDO1, FAM26F, CXCL9, and CXCL10 [6]. Time-course phosphoproteomic analyses during the first 24 hours of polarization have revealed dynamic phosphorylation events and kinase activation patterns that differ between M1 and M2 polarization, with MEK/ERK signaling identified as particularly important for M2 polarization [6].

Beyond the Dichotomy: Limitations and Refinements

While the M1/M2 paradigm provides a valuable conceptual framework, it represents a simplified view of macrophage biology that requires refinement in several aspects [3] [4]. The classification's primary limitation is its inability to fully capture the heterogeneity and plasticity of macrophage activation states observed in vivo [4]. Single-cell RNA sequencing studies have revealed multiple distinct macrophage subpopulations in tissues and tumors that don't align neatly with the M1/M2 dichotomy [8]. For example, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) include subsets such as C1Q+ macrophages in hepatocellular carcinomas and FN1+ TAMs in gliomas that exhibit unique transcriptional programs beyond traditional M1/M2 classification [8].

The polarization process exists along a spectrum rather than representing discrete endpoints, with macrophages often exhibiting mixed or intermediate phenotypes [4]. This continuum is influenced by complex combinations of signals in specific tissue microenvironments overlaid with temporal fluctuations [4]. Furthermore, the M1/M2 system may be inappropriate for describing the behavior of certain tissue-resident macrophage populations, such as alveolar macrophages, which minimally express many canonical M1 markers even in pro-inflammatory conditions [4].

Despite these limitations, the M1/M2 paradigm remains a useful heuristic tool for describing the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory extremes of macrophage function, particularly in the context of chronic inflammatory diseases where shifts along this spectrum have therapeutic implications [5] [4]. Ongoing research aims to develop more comprehensive classification systems that incorporate spatial, temporal, and functional heterogeneity while acknowledging the contextual nature of macrophage activation.

Therapeutic Implications and Targeting Strategies

The M1/M2 balance has significant implications for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment [5] [2]. In osteoarthritis, synovial macrophages polarized toward the M1 phenotype promote chronic inflammation and tissue destruction, while M2 macrophages facilitate tissue repair and resolution of inflammation [5] [2]. Similarly, in tumor microenvironments, M1-like TAMs generally exert antitumor effects, while M2-like TAMs promote angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and metastasis [8].

Therapeutic strategies targeting macrophage polarization include:

Inhibition of protumorigenic M2-like TAMs using CSF-1R inhibitors, CCL2 antagonists, or CD47-blocking antibodies to disrupt recruitment or survival pathways [8].

Reprogramming TAMs from M2 to M1 phenotype using nanoparticle-mediated delivery of IFN-γ or TLR agonists to stimulate antitumor immunity [8].

Targeting metabolic pathways such as MEK/ERK signaling or PPARγ-induced retinoic acid signaling that are critical for specific polarization states [6].

Epigenetic modulation using histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors that can selectively block M2 polarization without inhibiting M1 polarization [6].

These therapeutic approaches highlight the translational potential of targeting macrophage polarization in chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer, though challenges remain due to macrophage plasticity and heterogeneity across disease contexts [2] [8].

The M1/M2 paradigm of macrophage activation provides a foundational framework for understanding the remarkable functional plasticity of these immune cells. While representing a simplification of in vivo complexity, the classification remains valuable for conceptualizing the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory extremes of macrophage function in health and disease. The continuing refinement of this paradigm through single-cell technologies, spatial transcriptomics, and advanced metabolic imaging will enhance our understanding of macrophage biology in chronic inflammation and support the development of novel therapeutic strategies that target macrophage polarization states.

Macrophage polarization is a dynamic process whereby macrophages adopt distinct functional phenotypes in response to signals within their microenvironment [9]. This process is crucial for their diverse roles in immunity, tissue homeostasis, and repair [10]. The historical classification of macrophages into classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) types represents an oversimplification of a much more complex biological reality [11] [10]. Emerging research reveals that macrophage phenotypes exist along a continuous spectrum of activation states, with the M2 category encompassing several functionally distinct subtypes—M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d—each playing unique roles in chronic inflammatory processes [12] [13] [14].

Understanding this continuum is paramount for chronic inflammation research, as the imbalance and plasticity of these macrophage populations contribute significantly to disease pathogenesis [11] [14]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the macrophage polarization spectrum, with a detailed focus on the characteristics, regulatory mechanisms, and functions of M2 subtypes, providing researchers with the conceptual framework and methodological tools needed to advance therapeutic development.

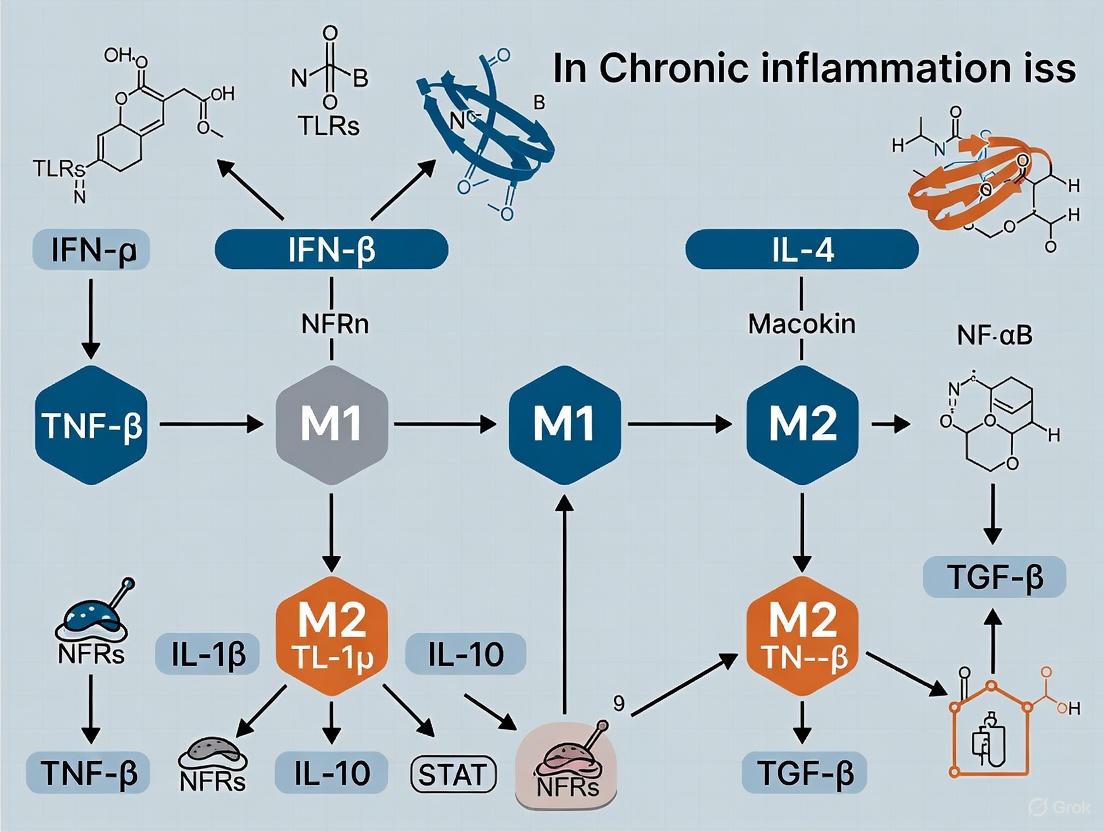

Beyond M1 and M2: The Continuum of Macrophage Activation

The M1/M2 dichotomy, originating from in vitro studies, has provided a valuable but limited framework for understanding macrophage biology [10]. In vivo, macrophages display a spectrum of phenotypic states that do not conform to this binary model [9]. Transcriptomic and epigenetic analyses have uncovered at least nine distinct directions of human macrophage activation, with numerous intermediate phenotypes existing between the M1 and M2 extremes [9]. This continuum is characterized by several key principles, as illustrated in the diagram below.

- Plasticity and Reversibility: Macrophage polarization states are not "terminally differentiated" but can change or reverse in response to evolving microenvironmental cues [9]. This plasticity is a critical feature in the transition from inflammation to resolution.

- Tissue-Specific Profiles: Tissue-resident macrophages exhibit unique transcriptional profiles shaped by their microenvironment, creating a diverse ecosystem of macrophage identities and functions throughout the body [11] [9].

- Coexistence of Phenotypes: Multiple macrophage phenotypes frequently coexist in tissues, with unique or hybrid phenotypes emerging in response to complex signal combinations [9] [10].

The M2 Subtypes: Detailed Characterization and Functional Profiles

The M2 category encompasses at least four distinct subtypes (M2a, M2b, M2c, M2d), each induced by specific stimuli and exhibiting unique marker expression and functional profiles [12] [13] [14].

M2 Subtypes: Inducing Factors, Key Markers, and Primary Functions

Table 1: Comprehensive Profile of M2 Macrophage Subtypes

| Subtype | Inducing Factors | Key Surface Markers | Secreted Cytokines & Mediators | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2a | IL-4, IL-13 [12] [14] | CD206, MHCII, Arg1, Dectin-1, DC-SIGN (CD209) [11] [12] | IL-10, TGF-β, IGF, Fibronectin, CCL17, CCL22 [12] [14] | Wound healing, tissue repair and fibrosis, allergy and anti-parasitic responses [12] [10] |

| M2b | Immune Complexes + TLR agonists or IL-1R agonists [12] [14] | CD86, MHCII, MR (CD206) [12] [14] | High IL-10, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL1 [12] [14] | Immunoregulation, regulation of inflammation, promotion of Th2 activation [12] |

| M2c | IL-10, TGF-β, Glucocorticoids [12] [14] | CD163, MR (CD206), MerTK [12] [14] | IL-10, TGF-β, CCL16, CCL18, MMPs [12] [13] [14] | Acquired deactivation, phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, immunosuppression, tissue remodeling [12] [10] |

| M2d | TLR antagonists + A2R agonists, IL-6 [12] [14] | (Similar to TAMs) [12] | High IL-10, VEGF, TGF-β, low IL-12 [12] | Angiogenesis, tumor progression (often referred to as TAMs) [12] [13] |

M2 Subtype-Specific Cytokine and Chemokine Profiles

Table 2: Quantitative Secretion Profiles of M2 Macrophage Subtypes

| Secreted Factor | M2a | M2b | M2c | M2d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | Moderate [12] | High [12] | High [12] | High [12] |

| IL-12 | Low [12] | Low [12] | Low [12] | Low [12] |

| TNF-α | Low | High [12] | Low | Low |

| IL-1β | Low | High | Low | Low |

| IL-6 | Low | High [12] | Low | Low |

| TGF-β | High [12] | Low | High [12] | High [12] |

| VEGF | Low | Low | Low | High [12] |

| CCL1 | Low | High [12] | Low | Low |

| CCL17/22 | High [12] | Low | Low | Low |

| CCL18 | Low | Low | High [13] [14] | Low |

Signaling Pathways Governing M2 Subtype Polarization

The differentiation of macrophages into specific M2 subtypes is controlled by distinct signaling pathways and transcription factors, as shown in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocols for M2 Subtype Analysis

In Vitro Generation of Human M2 Macrophage Subtypes

Protocol Objective: To generate and characterize human M2 macrophage subtypes from monocyte-derived macrophages.

Materials and Reagents:

- Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or isolated CD14+ monocytes

- Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (50 ng/mL)

- M2a Polarization Cocktail: IL-4 (20 ng/mL) + IL-13 (20 ng/mL) for 48 hours [12]

- M2b Polarization Cocktail: Immune complexes (IgG/ovalbumin) + LPS (10 ng/mL) or IL-1R agonists for 48 hours [12]

- M2c Polarization Cocktail: IL-10 (20 ng/mL) for 48 hours [12]

- M2d Polarization Cocktail: IL-6 (20 ng/mL) + adenosine A2A receptor agonist for 48 hours [12]

Procedure:

- Monocyte Isolation: Isolate CD14+ monocytes from PBMCs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS).

- Macrophage Differentiation: Culture monocytes with M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 6 days to generate M0 macrophages.

- M2 Polarization: On day 6, stimulate M0 macrophages with the appropriate polarization cocktail for 48 hours.

- Validation: Harvest cells for flow cytometry analysis of surface markers (see Table 1) and collect supernatant for cytokine analysis by ELISA.

Technical Notes: For M2b polarization under low serum conditions (as described in [15]), reduce serum concentration to 1% during polarization to enhance immunosuppressive characteristics, including increased expression of B7-H1, FasL, and TRAIL.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of M2 Subtypes

Panel Design:

- M2a Identification: CD206+ (high), CD86- (low), IL-10+ (moderate)

- M2b Identification: CD86+ (high), CD206+ (moderate), IL-10+ (high), TNF-α+

- M2c Identification: CD163+ (high), CD206+ (moderate), IL-10+ (high)

- M2d Identification: VEGF+ (high), IL-10+ (high), CD206+ (variable)

Instrument Setup: Configure flow cytometer (e.g., BD FACSCanto II, BD LSRFortessa) using BD FACSDiva Software with application settings for consistent resolution of macrophage populations [16]. Perform daily quality control with CS&T Research Beads to ensure optimal performance.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for M2 Macrophage Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, M-CSF) | Direct polarization of M2 subtypes in vitro | M-CSF for monocyte to macrophage differentiation; IL-4/IL-13 for M2a polarization [12] |

| Immune Complexes (IgG/OVA) | Induction of M2b phenotype | Combined with low-dose LPS for M2b polarization [12] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (anti-CD206, CD163, CD86, CD80) | Identification and quantification of M2 subtypes | Multicolor flow panel to distinguish M2a (CD206+ CD86-) from M2b (CD206+ CD86+) [16] [14] |

| ELISA Kits (IL-10, TGF-β, TNF-α, VEGF) | Quantification of subtype-specific cytokine secretion | Confirm M2b phenotype via high IL-10/TNF-α secretion; M2d via VEGF detection [12] |

| BD FACSDiva Software | Flow cytometer setup, acquisition, and analysis | Automated performance tracking and index sorting for single-cell analysis [16] |

| TLR Agonists/Antagonists (LPS, A2AR agonists) | Modulation of polarization pathways | M2d generation using TLR antagonists with A2AR activation [12] |

Research Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

The precise characterization of M2 subtypes opens promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Potential strategies include:

- Metabolic Reprogramming: Targeting metabolic pathways (e.g., arginine metabolism) that differentially regulate M1/M2 polarization [9].

- Epigenetic Modulation: Using inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) or histone modifiers to shift macrophage polarization states [11].

- Nanoparticle Targeting: Designing nanocarriers that specifically deliver therapeutic agents to distinct macrophage subsets based on their surface markers and physiological environments [17].

- Signaling Pathway Manipulation: Developing drugs that target key signaling nodes (STAT6, IRF4, PPARγ) to promote beneficial M2 functions or inhibit pathological ones [1] [9].

In chronic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, where an increased M1/M2 ratio drives pathology, promoting a shift toward M2b or M2c phenotypes could ameliorate inflammation [14]. Conversely, in tumor environments, reprogramming M2d-like tumor-associated macrophages toward an M1 phenotype could enhance anti-tumor immunity [10].

The macrophage activation spectrum extends far beyond the traditional M1/M2 dichotomy, encompassing a continuum of phenotypes with the M2 category containing at least four functionally distinct subtypes. Understanding the specific inducing signals, marker profiles, and functional capabilities of M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d macrophages provides a critical foundation for developing targeted therapies for chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. As single-cell technologies and spatial transcriptomics continue to reveal the complexity of macrophage biology in vivo, researchers and drug development professionals must adopt this nuanced spectrum model to advance the next generation of immunomodulatory treatments.

In the realm of immunology and chronic inflammation research, macrophages emerge as master regulators of tissue homeostasis, defense, and repair. Their remarkable functional plasticity, particularly their ability to polarize into distinct functional phenotypes, is orchestrated by a complex interplay of intracellular signaling pathways. Among these, three pathway families stand out as critical molecular switches: the Janus kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, the Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway, and the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway. These signaling cascades transduce extracellular signals into nuanced transcriptional programs that ultimately determine macrophage polarization states and functional outcomes in health and disease.

The significance of these pathways extends beyond fundamental biology to therapeutic applications, as their dysregulation underpins numerous chronic inflammatory diseases, autoimmune conditions, and cancer [18] [19] [20]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these pivotal signaling pathways, framed within the context of macrophage polarization in chronic inflammation research. We explore their molecular architectures, activation mechanisms, crosstalk, and experimental approaches for their investigation, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for advancing our understanding of immune regulation and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

Architectural Framework and Activation Dynamics

The JAK-STAT pathway serves as a paradigm for signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus, operating with remarkable architectural simplicity despite its diverse biological functions [18]. This pathway comprises three core components: cytokines and their cognate receptors, Janus kinases (JAKs), and Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STATs). The JAK family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases includes four members: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, which are differentially expressed across various cell types and play distinct roles in cytokine signaling [19]. The STAT family consists of seven transcription factors (STAT1-4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6) that serve as both signal transducers and transcription factors [20].

Pathway activation initiates when extracellular cytokines bind to their corresponding transmembrane receptors, inducing receptor dimerization or multimerization. This conformational change brings associated JAKs into proximity, enabling their trans-phosphorylation and activation. The activated JAKs then phosphorylate tyrosine residues on the receptor cytoplasmic tails, creating docking sites for STAT proteins via their Src homology 2 (SH2) domains. Once recruited, STATs are phosphorylated by JAKs on conserved tyrosine residues, leading to their dimerization, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding to regulate gene transcription [18].

Role in Macrophage Polarization and Inflammation

The JAK-STAT pathway is a critical determinant of macrophage polarization, primarily through its responsiveness to key cytokines in the microenvironment. STAT1 activation, triggered by IFN-γ and IL-12 signaling, drives polarization toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype [20]. These macrophages produce high levels of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and exhibit enhanced microbicidal and tumoricidal activity [21] [20].

Conversely, STAT6 and STAT3 activation promotes the alternative M2 activation program. IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation activates STAT6, while IL-6 signaling primarily activates STAT3, both leading to expression of anti-inflammatory and tissue-reparative genes including IL-10, TGF-β, and arginase 1 (Arg1) [20]. This M2 polarization supports Th2 responses, tissue remodeling, and inflammation resolution [21].

Table 1: JAK-STAT Pathway Components in Macrophage Polarization

| Pathway Component | Role in M1 Polarization | Role in M2 Polarization |

|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | Master regulator; induced by IFN-γ/IL-12 | Generally suppressed |

| STAT3 | Can be activated but context-dependent | Primary driver; activated by IL-6, IL-10 |

| STAT6 | Not involved | Primary driver; activated by IL-4, IL-13 |

| JAK1/JAK2 | Mediates IFN-γ signaling | Mediates IL-4/IL-13 signaling |

| TYK2 | Participates in IL-12 signaling | Limited role |

The JAK-STAT pathway's involvement in inflammatory and stress-related diseases extends to neuroinflammatory disorders, with pathway activation detected in brain regions such as the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum in conditions like Parkinson's disease [19]. The effectiveness of JAK inhibitors (Jakinibs) in chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis has expanded the therapeutic applications of targeting this pathway [19].

Experimental Analysis of JAK-STAT Signaling

Investigating JAK-STAT signaling in macrophage polarization requires a multi-faceted approach. Essential methodologies include:

- Phospho-flow Cytometry: Enables quantification of phosphorylated STAT proteins at single-cell resolution, allowing researchers to correlate STAT activation with surface markers of macrophage polarization.

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): Assesses STAT DNA-binding activity using nuclear extracts and radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing STAT-binding sequences.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Determines STAT occupancy at specific genomic loci in polarized macrophages, providing insights into transcriptional regulation.

- Luciferase Reporter Assays: Utilize STAT-responsive promoters to monitor pathway activity in response to polarizing stimuli or pharmacological inhibition.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for JAK-STAT Pathway Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| JAK Inhibitors | Tofacitinib (JAK1/3), Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2), Filgotinib (JAK1-selective) | Functional pathway blockade; therapeutic assessment |

| STAT Phosphorylation Antibodies | Anti-pSTAT1 (Y701), Anti-pSTAT3 (Y705), Anti-pSTAT6 (Y641) | Western blot, flow cytometry for activation monitoring |

| Cytokines for Polarization | IFN-γ (M1), IL-4/IL-13 (M2) | Macrophage polarization induction |

| STAT Knockdown Tools | siRNA, shRNA constructs | Loss-of-function studies |

Diagram 1: JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Polarization. This diagram illustrates the core JAK-STAT activation mechanism and its role in directing macrophage polarization toward M1 (pro-inflammatory) or M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes.

The NF-κB Signaling Pathway

Canonical and Non-Canonical Activation Cascades

NF-κB transcription factors serve as pivotal regulators of immunity, inflammation, and cell survival. The mammalian NF-κB family comprises five members: NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), RelA (p65), RelB, and c-Rel, which form various homo- and heterodimers with distinct transcriptional functions [22] [23]. These dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins in unstimulated cells [23].

The canonical NF-κB pathway is typically activated by proinflammatory stimuli such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [23] [24]. This pathway involves the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, consisting of catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ and the regulatory subunit NEMO (IKKγ) [22]. Upon activation, IKKβ phosphorylates IκBα, leading to its K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This process liberates predominantly RelA:p50 dimers for nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of target genes [23] [24].

The non-canonical pathway is activated by a more limited set of receptors, including CD40, lymphotoxin beta receptor, and B-cell activating factor (BAFF) receptor [24]. This pathway depends on NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)-mediated activation of IKKα, which phosphorylates p100, leading to its partial proteolytic processing to p52. The resulting RelB:p52 dimers translocate to the nucleus to regulate genes involved in lymphoid organ development and adaptive immunity [23] [24].

Inflammatory Gene Regulation and Macrophage Polarization

NF-κB is often described as a "master switch" for pro-inflammatory gene expression, playing an indispensable role in M1 macrophage polarization [20]. TLR engagement on macrophages by ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activates the canonical NF-κB pathway through either the MyD88-dependent or TRIF-dependent pathways, resulting in nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65/p50 complexes [20]. These dimers bind to κB enhancer elements in promoters of pro-inflammatory genes, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2, thereby amplifying inflammatory signals and reinforcing the M1 polarization state [23] [20].

The relationship between NF-κB and other polarization pathways is complex and involves significant crosstalk. STAT1 has been shown to activate NF-κB transcriptional activity, while STAT3 and NF-κB engage in mutual regulation to maintain M1/M2 homeostasis [20]. This intricate interplay creates a sophisticated regulatory network that fine-tunes macrophage responses to environmental cues.

Table 3: NF-κB Family Members and Their Roles in Signaling

| NF-κB Member | Structural Features | Primary Dimerization Partners | Role in Macrophage Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| RelA (p65) | Contains TAD | p50, c-Rel | Master driver of M1 polarization; pro-inflammatory gene transcription |

| p50/p105 | Lacks TAD; processed precursor | RelA, c-Rel, p50 | Transcriptional activator with TAD partners; repressor as homodimer |

| c-Rel | Contains TAD | p50, p65 | Enhances pro-inflammatory gene expression |

| RelB | Contains TAD | p52, p50 | Predominantly non-canonical pathway; lymphoid development |

| p52/p100 | Lacks TAD; processed precursor | RelB | Non-canonical pathway; B-cell maturation |

Experimental Approaches for NF-κB Pathway Analysis

Key methodologies for investigating NF-κB signaling in macrophage polarization include:

- IKK Kinase Assays: Measure IKK activity through in vitro kinase reactions using IκBα as substrate, often combined with immunoprecipitation of the IKK complex.

- Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Fractionation: Followed by Western blotting for NF-κB subunits to monitor nuclear translocation.

- EMSA with κB Probes: Assesses NF-κB DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts.

- NF-κB Reporter Cell Lines: Lentiviral transduction with κB-driven luciferase constructs enables dynamic monitoring of pathway activity in living macrophages.

- ChIP-Seq: Provides genome-wide mapping of NF-κB binding sites under different polarization conditions.

Diagram 2: NF-κB Canonical and Non-canonical Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates both the canonical (left) and non-canonical (right) NF-κB activation pathways, highlighting their distinct triggers, signaling components, and biological outcomes.

The PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

Metabolic Regulation and Signal Transduction

The PI3K/Akt pathway serves as a central regulator of cellular metabolism, growth, survival, and proliferation, integrating signals from extracellular growth factors, cytokines, and nutrients [25] [26]. This pathway begins with activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks), which are classified into three categories (I, II, and III) based on structure and substrate specificity [26]. Class I PI3Ks, particularly relevant in macrophage signaling, consist of a catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, p110γ, or p110δ) and a regulatory subunit (e.g., p85) [26].

Upon activation by receptor tyrosine kinases or G protein-coupled receptors, PI3K phosphorylates the membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3). This lipid second messenger recruits Akt (also known as PKB) and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) to the plasma membrane through their pleckstrin homology (PH) domains. PDK1 phosphorylates Akt at Threonine 308, while mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) phosphorylates Akt at Serine 473, resulting in full Akt activation [26]. The pathway is negatively regulated by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which dephosphorylates PIP3 back to PIP2, and by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylates Akt [26].

Role in Macrophage Polarization and Immunometabolism

The PI3K/Akt pathway exerts complex, context-dependent effects on macrophage polarization, influencing both M1 and M2 phenotypes through regulation of metabolic pathways and transcription factors. Akt activation generally promotes an M2-like polarization state through several mechanisms:

- mTORC1 Activation: Akt inhibits the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/2), leading to activation of mTORC1, which promotes translation of M2-associated genes and regulates cellular metabolism toward glycolytic and biosynthetic pathways supportive of M2 functions [26].

- FOXO Inhibition: Akt phosphorylates Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors, promoting their cytoplasmic sequestration and degradation, thereby relieving FOXO-mediated suppression of M2 gene expression [26].

- GSK3β Inhibition: Akt-mediated phosphorylation inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which normally suppresses M2 polarization, thus permitting alternative activation [26].

Despite this general pro-M2 bias, the PI3K/Akt pathway also contributes to specific aspects of M1 polarization, particularly in regulating inflammatory cytokine production and metabolic reprogramming to aerobic glycolysis. This apparent paradox highlights the pathway's complex, context-dependent functionality in macrophage biology.

Table 4: PI3K/Akt Pathway Components and Their Functions

| Pathway Component | Subtypes/Forms | Function in Pathway | Role in Macrophage Polarization |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K Catalytic Subunits | p110α, p110β, p110γ, p110δ | Phosphorylates PIP2 to PIP3 | p110α/β most relevant; initiates Akt signaling |

| Akt | Akt1, Akt2, Akt3 | Serine/threonine kinase; main effector | Generally promotes M2 polarization |

| PTEN | - | PIP3 phosphatase; pathway brake | Suppresses M2 polarization when active |

| PDK1 | - | Phosphorylates Akt at T308 | Required for partial Akt activation |

| mTORC2 | - | Phosphorylates Akt at S473 | Required for full Akt activation |

Experimental Methodologies for PI3K/Akt Pathway Investigation

Comprehensive analysis of PI3K/Akt signaling in macrophage polarization requires integrated experimental approaches:

- Lipid Blotting and Mass Spectrometry: Quantify PIP3 levels and other phosphoinositides in response to polarizing stimuli.

- Akt Activity Assays: Measure Akt kinase activity using immunoprecipitated Akt and recombinant substrates like GSK3 fusion proteins.

- Metabolic Profiling: Assess glycolytic flux, oxidative phosphorylation, and nutrient utilization using Seahorse extracellular flux analyzers and metabolic tracer studies.

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Utilize isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors (e.g., BYL719 for p110α, TGX221 for p110β), pan-PI3K inhibitors (e.g., LY294002, wortmannin), and Akt inhibitors (e.g., MK-2206) to dissect pathway requirements.

- Genetic Approaches: Employ conditional knockout mice (e.g., myeloid-specific PTEN deletion) or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to manipulate pathway components in primary macrophages.

Diagram 3: PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Polarization. This diagram illustrates PI3K/Akt activation and its downstream effectors, showing the pathway's predominant role in promoting M2 macrophage polarization while contributing to selected M1 functions.

Pathway Crosstalk in Macrophage Polarization

Integrated Signaling Networks

The signaling pathways governing macrophage polarization do not operate in isolation but rather form an intricate network of synergistic, antagonistic, and compensatory interactions. Understanding this crosstalk is essential for comprehending the robustness and plasticity of macrophage responses in chronic inflammation.

JAK-STAT and NF-κB Crosstalk: Multiple points of integration exist between these pathways. STAT1 can activate NF-κB transcriptional activity, creating positive feedback that amplifies M1 polarization [20]. Simultaneously, STAT3 and NF-κB engage in mutual regulation to maintain M1/M2 homeostasis, with STAT3 often counterbalancing NF-κB-driven inflammation [20]. Additionally, NF-κB induces expression of various cytokines that signal through JAK-STAT pathways, creating autocrine and paracrine reinforcement loops.

PI3K/Akt and NF-κB Interactions: Akt can directly phosphorylate IKKα, enhancing NF-κB activation and potentially reinforcing M1 polarization despite Akt's general pro-M2 bias [26]. This exemplifies the context-dependent nature of pathway crosstalk, where the same molecule can contribute to apparently opposing functional outcomes depending on timing, subcellular localization, and interaction partners.

PI3K/Akt and JAK-STAT Interplay: Akt-mediated regulation of FOXO transcription factors influences STAT signaling, as FOXOs can modulate expression of STAT-dependent genes [26]. Additionally, mTORC1, a key Akt effector, regulates translation of STAT transcripts and proteins, creating another layer of integration between these pathways.

Experimental Framework for Analyzing Pathway Crosstalk

Investigating these complex interactions requires sophisticated experimental designs:

- Multiplex Phosphoprotein Analysis: Simultaneous measurement of phosphorylation states across multiple pathways using phospho-flow cytometry or Luminex arrays.

- Pathway Co-inhibition Studies: Combined pharmacological targeting of two or more pathways to identify synergistic or antagonistic interactions.

- Time-Resolved Activation Mapping: Sequential analysis of pathway activation following polarizing stimuli to establish hierarchical relationships.

- Computational Modeling: Integration of experimental data into mathematical models to predict system behavior under different perturbation conditions.

- Multi-Omics Integration: Correlation of phosphoproteomic data with transcriptomic and epigenomic profiles to connect signaling events with functional outcomes.

Table 5: Pathway Crosstalk in Macrophage Polarization

| Pathway Interaction | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| STAT1 → NF-κB | STAT1 enhances NF-κB transcriptional activity | Enhanced M1 polarization; amplified inflammation |

| STAT3 NF-κB | Mutual regulation; balance maintenance | M1/M2 homeostasis; prevention of excessive polarization |

| Akt → IKK/NF-κB | Akt phosphorylates IKKα | Context-dependent enhancement of NF-κB signaling |

| Akt → FOXO → STAT | Akt inhibits FOXO, modulating STAT-dependent genes | Fine-tuning of M2 polarization programs |

| mTORC1 → STAT | mTORC1 regulates STAT translation | Control of STAT protein levels and activity |

Therapeutic Targeting and Research Applications

Translational Implications for Chronic Inflammation

The pivotal role of JAK-STAT, NF-κB, and PI3K/Akt pathways in macrophage polarization and chronic inflammation has made them attractive therapeutic targets. Several targeting strategies have emerged:

JAK-STAT Targeting: JAK inhibitors (Jakinibs) have demonstrated clinical efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases [19]. Next-generation inhibitors with improved selectivity, such as filgotinib (JAK1-selective) and upadacitinib, offer enhanced therapeutic profiles with reduced off-target effects [19]. Combination therapies pairing Jakinibs with biological agents represent a promising frontier for enhancing specificity and efficacy.

NF-κB Pathway Modulation: Therapeutic strategies include IKK inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors (preventing IκB degradation), nuclear translocation inhibitors, and compounds interfering with NF-κB DNA binding [22] [23]. The challenge lies in achieving sufficient pathway suppression for therapeutic benefit while avoiding unacceptable immunosuppression, given NF-κB's fundamental role in host defense.

PI3K/Akt Pathway Inhibition: Isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors such as alpelisib (targeting p110α) are FDA-approved for PIK3CA-mutated cancers and are being investigated for inflammatory applications [25] [27]. Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors and Akt-specific inhibitors are in clinical development, with combination therapies showing promise in overcoming resistance mechanisms [27].

Research Toolkit for Investigating Pathway Roles in Macrophage Polarization

A comprehensive approach to studying these pathways requires well-defined experimental systems and reagents:

Table 6: Essential Research Tools for Signaling Pathway Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Primary human monocyte-derived macrophages, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages, THP-1 human monocytic cell line | Primary cells most physiologically relevant; cell lines offer reproducibility |

| Polarization Inducers | LPS + IFN-γ (M1), IL-4/IL-13 (M2), IL-10 + TGF-β (M2c) | Standardized polarization protocols enable cross-study comparisons |

| Pathway Reporters | Lentiviral STAT-, NF-κB-, or Akt-responsive luciferase constructs | Enable real-time monitoring of pathway activity in live cells |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | JAKi: Tofacitinib; IKKi: BMS-345541; PI3Ki: LY294002; Akti: MK-2206 | Use at validated concentrations; assess selectivity limitations |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 for gene editing, siRNA/shRNA for knockdown, Conditional knockout mice | Enable specific pathway component manipulation |

| Lemildipine | Lemildipine | High-purity Lemildipine for research applications. This calcium channel blocker is for laboratory analysis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Lersivirine | Lersivirine, CAS:473921-12-9, MF:C17H18N4O2, MW:310.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The JAK-STAT, NF-κB, and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways represent fundamental molecular switches that orchestrate macrophage polarization and function in chronic inflammation. While each pathway possesses distinct activation mechanisms and downstream effectors, their extensive crosstalk creates a sophisticated regulatory network that enables precise control of immune responses. Continued elucidation of these signaling circuits, particularly in the context of human diseases, will undoubtedly yield new therapeutic opportunities for managing chronic inflammatory conditions, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. The experimental frameworks and technical approaches outlined in this review provide a foundation for advancing our understanding of these critical molecular switches and their integrated control of immune cell function.

Macrophages, as versatile components of the innate immune system, exhibit remarkable plasticity in response to microenvironmental signals. Their activation state, or polarization, is fundamentally linked to specific metabolic reprogramming that dictates their function in health and disease [28]. In the context of chronic inflammation, such as persistent infections or degenerative diseases, this metabolic switching plays a critical role in either perpetuating or resolving inflammatory responses [29] [30]. The classic dichotomy of macrophage polarization describes pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, each relying on distinct metabolic pathways to fuel their functions [28] [31]. M1 macrophages predominantly utilize glycolysis for rapid energy production, even under aerobic conditions, while M2 macrophages rely primarily on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for efficient ATP generation [31] [32]. This metabolic reprogramming is not merely a consequence of activation but an essential regulatory mechanism that controls macrophage phenotype and function through metabolic intermediates that act as signaling molecules [33] [34]. Understanding the intricate relationship between macrophage polarization and metabolic reprogramming provides crucial insights into the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory conditions and reveals potential therapeutic targets for modulating immune responses.

Metabolic Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

Macrophages utilize five primary metabolic pathways to generate energy and biosynthetic precursors: glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), fatty acid metabolism (including both fatty acid oxidation and synthesis), and amino acid metabolism [29] [30]. The configuration and flux through these pathways vary dramatically between different polarization states, creating a metabolic signature that supports specific immune functions.

Glycolysis occurs in the cytoplasm and involves the breakdown of glucose to pyruvate, with a net gain of two ATP molecules per glucose molecule [33]. Under aerobic conditions, pyruvate typically enters the mitochondria for oxidation in the TCA cycle, but in M1 macrophages, this process is disrupted, and pyruvate is preferentially converted to lactate [29]. The TCA cycle, located in the mitochondrial matrix, normally generates reducing equivalents (NADH and FADH2) that feed into the electron transport chain to support OXPHOS [29] [35]. The PPP branches from glycolysis and produces NADPH for biosynthetic reactions and antioxidant defense, along with pentose sugars for nucleotide synthesis [31]. Fatty acid metabolism encompasses both catabolic (β-oxidation) and anabolic (synthesis) processes, while amino acid metabolism, particularly glutamine metabolism, provides carbon and nitrogen sources for biomass production and TCA cycle intermediates [29].

M1 Macrophages: Glycolytic Metabolism

M1 macrophages, activated by stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), undergo a metabolic shift toward glycolysis, similar to the Warburg effect observed in cancer cells [32] [34]. This metabolic reprogramming supports their pro-inflammatory functions and antimicrobial activity through several interconnected mechanisms.

Enhanced Glycolytic Flux: M1 macrophages increase their expression of glucose transporters (GLUT1 and GLUT6) and glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase (HK1, HK2), phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and the isoform M2 of pyruvate kinase (PKM2) [29] [31]. This increased glycolytic capacity provides rapid ATP generation to meet the energy demands of inflammation and produces metabolic intermediates that support biosynthetic processes. The transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) plays a central role in driving this glycol switch, upregulating glycolytic genes even under normoxic conditions [32].

Disrupted TCA Cycle: In M1 macrophages, the TCA cycle is broken at several points, leading to accumulation of intermediates that serve signaling functions [29] [32]. Citrate is exported from mitochondria and used for fatty acid synthesis and the production of prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO) [32]. Succinate accumulates and stabilizes HIF-1α by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases, further promoting glycolysis and IL-1β production [32]. Itaconate, derived from the TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate, has antimicrobial effects and regulates inflammatory responses [31].

Pentose Phosphate Pathway Activation: The PPP is upregulated in M1 macrophages, generating NADPH that fuels the oxidative burst via NADPH oxidase (NOX2) and supports inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity [31]. This pathway also provides ribose-5-phosphate for nucleotide synthesis, which is necessary for the production of inflammatory mediators.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Enzymes and Their Roles in M1 Macrophages

| Enzyme | Function | Role in M1 Polarization |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | Master regulator of glycolysis | Upregulates glycolytic genes, promotes inflammatory responses [32] |

| PKM2 | Glycolytic enzyme; pyruvate kinase isoform | Regulates inflammasome activation; promotes IL-1β production [31] |

| iNOS | Produces nitric oxide from arginine | Inhibits mitochondrial respiration; promotes bacterial killing [32] |

| PFKFB3 | Synthesis of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate | Allosterically activates PFK-1; drives glycolytic flux [31] |

M2 Macrophages: Oxidative Phosphorylation

In contrast to M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages (activated by IL-4 or IL-13) rely primarily on oxidative metabolism to support their functions in tissue repair, immunoregulation, and parasite clearance [28] [31]. This metabolic phenotype is characterized by intact mitochondrial pathways and efficient energy production.

Oxidative Phosphorylation: M2 macrophages maintain high rates of OXPHOS, generating ATP through the complete oxidation of glucose [31]. This process begins with glycolysis, but unlike in M1 cells, the pyruvate produced enters the mitochondria and is converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase. Acetyl-CoA then feeds into the TCA cycle, producing NADH and FADH2 that drive the electron transport chain to produce substantial ATP yields [35].

Fatty Acid Oxidation: A hallmark of M2 polarization is the increased reliance on fatty acid oxidation (FAO) [29] [30]. Fatty acids are broken down through β-oxidation in the mitochondria, generating acetyl-CoA that fuels the TCA cycle and producing NADH and FADH2 for the electron transport chain. This metabolic pathway supports the longevity and tissue repair functions of M2 macrophages. The transcription factor PPAR-γ and its coactivator PGC-1β are key regulators of FAO in M2 macrophages [28].

Complete TCA Cycle Function: Unlike the broken TCA cycle in M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages maintain an intact cycle that efficiently generates energy and precursors [29]. Glutamine metabolism is particularly important in M2 cells, providing α-ketoglutarate that enters the TCA cycle and supports ATP production [29]. Additionally, α-ketoglutarate derived from glutamine catabolism can inhibit M1 polarization by suppressing the NF-κB pathway, thereby reinforcing the M2 phenotype [29].

Table 2: Key Metabolic Enzymes and Their Roles in M2 Macrophages

| Enzyme/Pathway | Function | Role in M2 Polarization |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Oxidation | Mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids | Supports OXPHOS; provides acetyl-CoA for TCA cycle [29] |

| PPAR-γ | Nuclear receptor transcription factor | Upregulates genes for fatty acid uptake and oxidation [28] |

| Arginase-1 | Hydrolyzes arginine to ornithine and urea | Promotes polyamine and proline synthesis for tissue repair [28] |

| Glutamine Metabolism | Provides carbon and nitrogen sources | Sustains TCA cycle via α-ketoglutarate [29] |

Signaling Pathways Regulating Metabolic Reprogramming

HIF-1α Signaling in M1 Macrophages

The hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) pathway serves as a master regulator of the metabolic switch to glycolysis in M1 macrophages, acting as a central node integrating inflammatory and metabolic signals [32].

Figure 1: HIF-1α Signaling in M1 Macrophage Metabolic Reprogramming. This diagram illustrates how LPS and IFN-γ signaling converge on HIF-1α activation to promote glycolysis and inflammation.

PPAR-γ and PGC-1β Signaling in M2 Macrophages

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and its coactivator PGC-1β form a key signaling axis that promotes oxidative metabolism in M2 macrophages [28].

Figure 2: PPAR-γ/PGC-1β Signaling in M2 Macrophage Oxidative Metabolism. This diagram shows the signaling pathway through which IL-4 and IL-13 promote oxidative metabolism in M2 macrophages.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Macrophage Metabolism

Inducing and Validating Macrophage Polarization

M1 Polarization Protocol:

- Isolate human mononuclear cells from peripheral blood or use murine bone marrow-derived progenitors

- Differentiate monocytes into macrophages using 50 ng/mL M-CSF for 6-7 days

- Polarize macrophages toward M1 phenotype using 100 ng/mL LPS + 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 18-24 hours [28] [32]

- Validate polarization by measuring surface markers (CD80, CD86) via flow cytometry and cytokine production (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α) via ELISA [28]

M2 Polarization Protocol:

- Differentiate monocytes as described above

- Polarize macrophages toward M2 phenotype using 20 ng/mL IL-4 or IL-13 for 18-24 hours [28]

- Validate polarization by measuring surface markers (CD206, CD163) via flow cytometry and cytokine production (IL-10, TGF-β) via ELISA [28]

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Extracellular Flux Analysis:

- Seed polarized macrophages in XF96 or XF24 cell culture microplates (40,000-100,000 cells/well)

- Replace culture medium with unbuffered assay medium (XF Base Medium supplemented with 1-10 mM glucose, 1-2 mM glutamine, and 1 mM pyruvate)

- Measure glycolytic rate using the Glycolysis Stress Test:

- Measure oxidative phosphorylation using the Mito Stress Test:

- Baseline measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR)

- Inject 1-2 μM oligomycin to measure ATP-linked respiration

- Inject 0.5-1 μM FCCP to measure maximum respiratory capacity

- Inject 0.5 μM rotenone/antimycin A to measure non-mitochondrial respiration [31]

Metabolomic Profiling:

- Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol/acetonitrile/water solutions

- Extract intracellular metabolites

- Analyze metabolites using:

Research Reagent Solutions for Macrophage Metabolism Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Macrophage Metabolic Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polarization Inducers | LPS (100 ng/mL), IFN-γ (20 ng/mL), IL-4 (20 ng/mL), IL-13 (20 ng/mL) | Induce M1 or M2 macrophage polarization [28] [32] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM), Oligomycin (1 μM), FCCP (0.5-1 μM), Rotenone (0.5 μM), Antimycin A (0.5 μM) | Inhibit specific metabolic pathways for flux analysis and functional studies [31] [32] |

| Metabolic Probes | 2-NBDG (fluorescent glucose analog), MitoTracker dyes, TMRE (mitochondrial membrane potential dye) | Visualize and quantify nutrient uptake and mitochondrial function [32] |

| Antibodies for Validation | Anti-CD86, Anti-CD206, Anti-iNOS, Anti-Arg1 | Confirm macrophage polarization status via flow cytometry or Western blot [28] |

| Cytokine Assays | ELISA kits for IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, TGF-β | Quantify inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion [28] |

Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammation

In chronic infections and inflammatory diseases, the dynamic interplay between M1 and M2 macrophage populations and their metabolic programs plays a crucial role in disease progression and resolution [29] [30]. During early infection, M1 macrophages dominate the immune response, utilizing glycolysis to rapidly produce ATP and inflammatory mediators to combat pathogens [29]. However, as infections persist, many pathogens have evolved mechanisms to manipulate macrophage metabolism to facilitate immune evasion and ensure their long-term survival [29] [30].

In tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the pathogen induces metabolic reprogramming that shuts down glycolysis in infected macrophages, creating a favorable environment for bacterial persistence [31]. Similarly, in obesity-associated chronic inflammation, alterations in macrophage substrate availability (increased fatty acids and glucose) drive polarization toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes, contributing to insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction [36]. The transition from M1 to M2 metabolism during the resolution phase of inflammation is characterized by a metabolic rebalancing, with restoration of the TCA cycle, increased OXPHOS, and enhanced fatty acid oxidation [29]. Failure of this metabolic transition can result in persistent inflammation or fibrosis, highlighting the importance of understanding these processes for therapeutic development.

The metabolic reprogramming of macrophages between glycolytic and oxidative states represents a fundamental mechanism underlying their polarization and function in chronic inflammation. The distinct metabolic signatures of M1 and M2 macrophages not only reflect their activation states but actively regulate their pro-inflammatory versus tissue-repair functions through metabolic intermediates that serve as signaling molecules. The intricate relationship between metabolism and macrophage function reveals numerous potential therapeutic targets for modulating immune responses in chronic inflammatory diseases, including metabolic enzymes, signaling pathways, and substrate availability. Future research focusing on spatiotemporal control of macrophage metabolism and the development of targeted delivery systems for metabolic modulators holds promise for innovative treatments that can precisely manipulate macrophage polarization to resolve chronic inflammation while preserving essential immune functions.

Macrophages, as crucial sentinels of the innate immune system, exhibit remarkable plasticity, allowing them to respond to microenvironmental cues by polarizing into distinct functional phenotypes. This process is central to both the initiation and resolution of inflammation in chronic inflammatory diseases. Beyond their traditional roles as structural components and energy sources, lipids and their bioactive metabolites have emerged as key regulators of macrophage polarization, shaping immune responses and inflammatory outcomes [37]. The application of lipidomics—a subset of metabolomics focused on the systematic identification and quantification of lipids—has begun to unveil the profound complexity of the lipidome and its intricate relationship with macrophage fate [38]. This technical guide explores the role of bioactive lipids and lipidomics in understanding macrophage polarization, framed within the context of chronic inflammation research. By integrating quantitative lipid profiling, detailed experimental protocols, and pathway visualizations, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for investigating lipid-mediated mechanisms in immunometabolic diseases.

Macrophage Polarization: A Spectrum of Functional States

Macrophages exist on a continuum of activation states, broadly categorized into classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) phenotypes, each with distinct functional roles and metabolic characteristics.

- M1 Macrophages (Pro-inflammatory): M1 polarization is typically induced by stimuli such as interferon-gamma (IFNγ) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [39] [40]. These cells express surface markers like CD80, CD86, and MHC-II, and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α [39]. A key metabolic hallmark is their reliance on aerobic glycolysis, with disruptions in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle leading to accumulation of citrate and succinate. They also produce high levels of nitric oxide (NO) via inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which confers microbicidal properties [37] [41].

- M2 Macrophages (Anti-inflammatory/reparative): M2 polarization is driven by cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 [37] [39]. These cells express markers like CD206, CD163, and arginase-1 (Arg1) [39]. They primarily depend on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and feature an intact TCA cycle. Their metabolic program supports roles in immune regulation, tissue repair, and wound healing [37] [41].

Table 1: Characteristics of Macrophage Polarization States

| Feature | M1 (Classically Activated) | M2 (Alternatively Activated) |

|---|---|---|

| Activating Stimuli | IFNγ, LPS [39] [40] | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10 [37] [40] |

| Key Markers | CD80, CD86, MHC-II, iNOS [39] | CD206, CD163, Arg1, FIZZ1 [39] |

| Secreted Factors | IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, NO, ROS [39] | IL-10, TGF-β, Arg1 [39] |

| Primary Metabolism | Aerobic Glycolysis [37] | Oxidative Phosphorylation, Fatty Acid Oxidation [37] |

| Primary Functions | Host defense, Pro-inflammation, Antimicrobial [39] | Tissue repair, Immunoregulation, Anti-inflammatory [39] |

Lipid Metabolism in Macrophage Polarization

Lipid metabolism is a central regulator of macrophage polarization, influencing membrane composition, energy production, and the generation of signaling molecules.

Metabolic Reprogramming of Lipids

- M1 Macrophages: Pro-inflammatory activation is associated with increased fatty acid synthesis (FAS). Citrate, exported from the mitochondria, is converted to acetyl-CoA by ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) in the cytosol. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) then catalyze the de novo synthesis of saturated fatty acids like palmitate [37]. This metabolic shift supports membrane remodeling for phagosome formation and provides precursors for lipid signaling molecules.

- M2 Macrophages: The anti-inflammatory phenotype relies on fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to fuel OXPHOS. M2 macrophages show increased uptake of exogenous fatty acids via receptors like CD36 and utilize the catabolic FAO pathway to generate energy, which supports their long-term tissue repair functions [37] [41].

Bioactive Lipid Signaling

Bioactive lipids, particularly eicosanoids derived from arachidonic acid (AA), are potent mediators that shape macrophage function.

- M1-Associated Signaling: In M1 macrophages, cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) releases AA from membrane phospholipids. Free AA is subsequently metabolized by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) to produce pro-inflammatory prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2) or by 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) to generate leukotrienes (e.g., LTB4), which amplify the inflammatory response [37].

- M2-Associated Signaling: The role of lipid mediators in M2 polarization is an area of active investigation. However, certain lysophospholipids, such as those generated by secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2), have been implicated in processes like phagocytosis [37]. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators (e.g., resolvins, protectins) often derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids like EPA and DHA, are crucial for inflammation resolution, a process in which M2-like macrophages play a key role.

Diagram 1: Lipid signaling pathways in macrophage polarization. M1 and M2 stimuli trigger distinct metabolic programs and enzymatic activities, leading to the production of specialized lipid mediators that dictate functional outcomes.

Lipidomics: Decoding the Macrophage Lipidome

Lipidomics provides a powerful set of analytical techniques for the comprehensive study of lipids in biological systems, enabling the characterization of macrophage polarization states beyond conventional gene and protein markers [42] [38].

Core Lipidomics Workflows

A typical lipidomics analysis involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to data analysis, as outlined below.

Diagram 2: Standard lipidomics workflow. The process involves lipid extraction from biological samples, chromatographic separation (or direct infusion), detection by mass spectrometry, and subsequent data analysis for lipid identification and quantification.

Key Methodologies and Instrumentation

Mass spectrometry (MS) is the cornerstone of modern lipidomics. The choice of MS platform depends on the research goals, whether for untargeted discovery or targeted, quantitative analysis.

Table 2: Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Technologies for Lipidomics

| Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Common Application in Macrophage Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-Triple Quadrupole (LC-QqQ) | High sensitivity and specificity in MRM mode; ideal for targeted quantification of known lipids [42]. | Lower mass resolution than QTOF or Orbitrap; less effective for untargeted discovery [42]. | Targeted profiling of eicosanoids and specific phospholipid classes [43]. |

| LC-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (LC-QTOF) | High mass accuracy and resolution; suitable for untargeted profiling and identification of unknown lipids [42]. | Lower sensitivity than MRM in QqQ; longer run times; higher instrument cost [42]. | Global, untargeted lipidomics to discover novel lipid markers of polarization [38]. |

| Shotgun Lipidomics | High-throughput; no chromatography; reduced analysis time; suitable for limited sample material [38]. | Cannot distinguish isobaric lipids; ion suppression effects in complex mixtures [38]. | High-throughput screening of major lipid classes in macrophage subpopulations [38]. |

| LC-Orbitrap | Very high mass resolution and accuracy; excellent for structural elucidation and complex mixtures [42]. | High cost; longer run times; requires expert operation [42]. | Deep characterization of lipidomes and identification of low-abundance lipid species. |

Quantitative Lipid Profiling in Polarized Macrophages

Lipidomics studies have revealed specific alterations in the lipidome during macrophage polarization. The following table summarizes key quantitative changes observed in human and murine macrophages.

Table 3: Select Lipidomic Changes in Polarized Macrophages from Experimental Studies

| Lipid Class | Observed Change | Experimental Model | Potential Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids (PC, PE, PS, PI) | Shift from saturated/monounsaturated to polyunsaturated species in M1 and M2 vs. monocytes/M0 [43]. | Human THP-1 monocyte cell line. | Increased membrane fluidity and provision of substrates for lipid mediator synthesis. |

| Lysophosphatidylinositol (lysoPI) | Significantly increased in M2 vs. M1 macrophages [43]. | Human THP-1 and mouse RAW264.7 cell lines. | Potential role in M2 polarization and anti-inflammatory processes [43]. |

| Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) | Upregulated in M1 macrophages [43]. | Human THP-1 monocyte cell line. | Association with pro-inflammatory activation. |

| Lysophosphatidylserine (lysoPS) | Decreased in M2 vs. M1 macrophages [43]. | Human THP-1 monocyte cell line. | Potential marker for distinguishing M1 from M2 phenotypes. |

| Arachidonic Acid (AA) in Phospholipids | Increased mobilization in M1 macrophages [40]. | Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). | Provides substrate for pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production. |

| Thromboxane Aâ‚‚ (TXAâ‚‚) | Identified as a specific marker of M1 polarization [40]. | Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). | Contributes to pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic state. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Lipidomics of Polarized Human Macrophages

The following protocol, adapted from published methodologies [40] [43], details the process for generating and analyzing polarized human macrophages.

Monocyte Isolation and Macrophage Differentiation

- Source Cells: Use human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from healthy donors via density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). Isolate monocytes from PBMCs by negative selection using a commercial kit (e.g., Miltenyi Monocyte Isolation Kit II) [40].

- Exclusion Criteria: Consider donor health status. Typical exclusions include fever >101°F in preceding 48 hours, current antibiotic or immunosuppressive therapy, chronic viral infection, or active cancer [40].

- Differentiation: Culture isolated monocytes (e.g., 1.35 x 10ⶠcells/well in a 6-well plate) for 7 days in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 ng/mL recombinant human M-CSF to differentiate them into monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) or M0 macrophages [40]. Allow cells to rest for 24 hours in M-CSF-free medium before polarization.

Macrophage Polarization

Treat differentiated MDMs for 24 hours with specific polarizing stimuli in RPMI medium with 5% FBS [40]:

- M1 Polarization: 20 ng/mL IFNγ + 100 ng/mL ultrapure LPS from E. coli K12.

- M2a Polarization: 20 ng/mL IL-4.

- M2c Polarization: 20 ng/mL IL-10.

- M0 (Resting): Vehicle control.

Lipid Extraction and Sample Preparation

- Extraction Method: Use a modified Folch method for biphasic lipid extraction [40] [38].

- Wash polarized macrophage cells and scrape cell pellets.

- Add 500 μL of 5% HCl and 750 μL of Folch solution (chloroform:methanol, 2:1 v/v, containing an antioxidant like 17 mg/L butylated hydroxytoluene) to the pellet.

- Vortex vigorously and centrifuge briefly (e.g., 15,000 rpm).

- Carefully recover the lower organic phase, which contains the lipids.

- Sample Storage: Dry the organic extracts under a gentle stream of nitrogen or using a vacuum concentrator. Store dried lipid extracts at -80°C until MS analysis [40].

Lipidomic Analysis by Mass Spectrometry

- Instrumentation: Employ liquid chromatography coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-QqQ) operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode for targeted, quantitative analysis [43]. Alternatively, use LC-QTOF for untargeted profiling.

- Chromatography: Utilize reverse-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) with a C18 column for separation based on lipid hydrophobicity. A typical mobile phase system is a gradient of water and methanol or acetonitrile, often with additives like 10 mM ammonium formate to enhance ionization [40] [43].

- Quantification: Use internal standards for precise quantification. A commercial SPLASH Lipidomix standard cocktail, containing stable isotope-labeled or unnatural lipid species representing major lipid classes, is added to each sample prior to extraction. Quantify individual lipid species by comparing their peak areas to the area of the corresponding internal standard [38].

Data Analysis and Validation

- Bioinformatics: Use specialized software (e.g., LipidSearch, MarkerView, or open-source platforms) for peak picking, alignment, and lipid identification based on precursor mass, fragmentation patterns, and retention time [38].