Mathematical Modeling of Inflammatory Marker Dynamics: From Bench to Bedside in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mathematical modeling frameworks for inflammatory biomarker dynamics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mathematical Modeling of Inflammatory Marker Dynamics: From Bench to Bedside in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mathematical modeling frameworks for inflammatory biomarker dynamics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of quantitative inflammation modeling, including key biomarkers like TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP. The review delves into methodological approaches such as Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) and Delay Differential Equations (DDEs), and their application in translational research, from LPS challenge studies to clinical sepsis and organ-specific inflammation. It further addresses critical challenges in model calibration, stability, and optimization, and concludes with a comparative analysis of model validation techniques across experimental and clinical settings, synthesizing key takeaways for future biomedical research.

Core Principles and Quantitative Foundations of Inflammatory Biomarker Dynamics

Biomarker Profiles and Clinical Significance

Inflammatory biomarkers are critical for diagnosing, prognosticating, and guiding therapeutic interventions across numerous pathological conditions. The dynamic interplay between these mediators can be quantitatively analyzed through mathematical modeling to predict disease trajectories and treatment responses. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of five key inflammatory biomarkers.

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Biomarkers: Characteristics and Clinical Associations

| Biomarker | Full Name | Primary Source | Key Biological Functions | Peak Concentration Timeline | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha | Macrophages, T cells [1] | Master regulator of inflammation; upregulates other cytokines; induces fever and apoptotic cell death [1] | 90-120 minutes post-stimulus [2] | Sepsis severity, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease [1] [3] |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 | Macrophages, T cells [1] | Pro-inflammatory; stimulates acute phase protein production (e.g., CRP); B and T cell recruitment [1] [4] | 90-120 minutes post-stimulus [2] | Strong predictor of 30-day mortality; correlates with stroke severity and infarct volume; reduced benefit from nutritional therapy at high levels [2] [4] |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 | Macrophages, other immune cells [1] | Potent chemokine; recruits neutrophils, basophils, and T cells to site of inflammation [1] | Information Not Specified in Search Results | Infection response, particularly to S. aureus [1] [5] |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 | Macrophages, T cells [1] | Anti-inflammatory; inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6); critical for immune regulation and homeostasis [1] | Information Not Specified in Search Results | Regulation of immune responses; prevention of host damage during infection [1] |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein | Liver (in response to IL-6) [2] | Acute-phase protein; activates complement system; promotes phagocytosis [2] [4] | 1-2 days post-initial trigger [2] | Rapid elevation post-stroke aids diagnosis; levels >100 mg/L associated with diminished response to nutritional therapy [2] [4] |

Mathematical Modeling of Inflammatory Dynamics

Mathematical models provide a powerful framework for understanding the complex, non-linear dynamics of inflammatory biomarker interactions and their systemic effects. Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) are commonly used to simulate the concentration changes of these mediators over time.

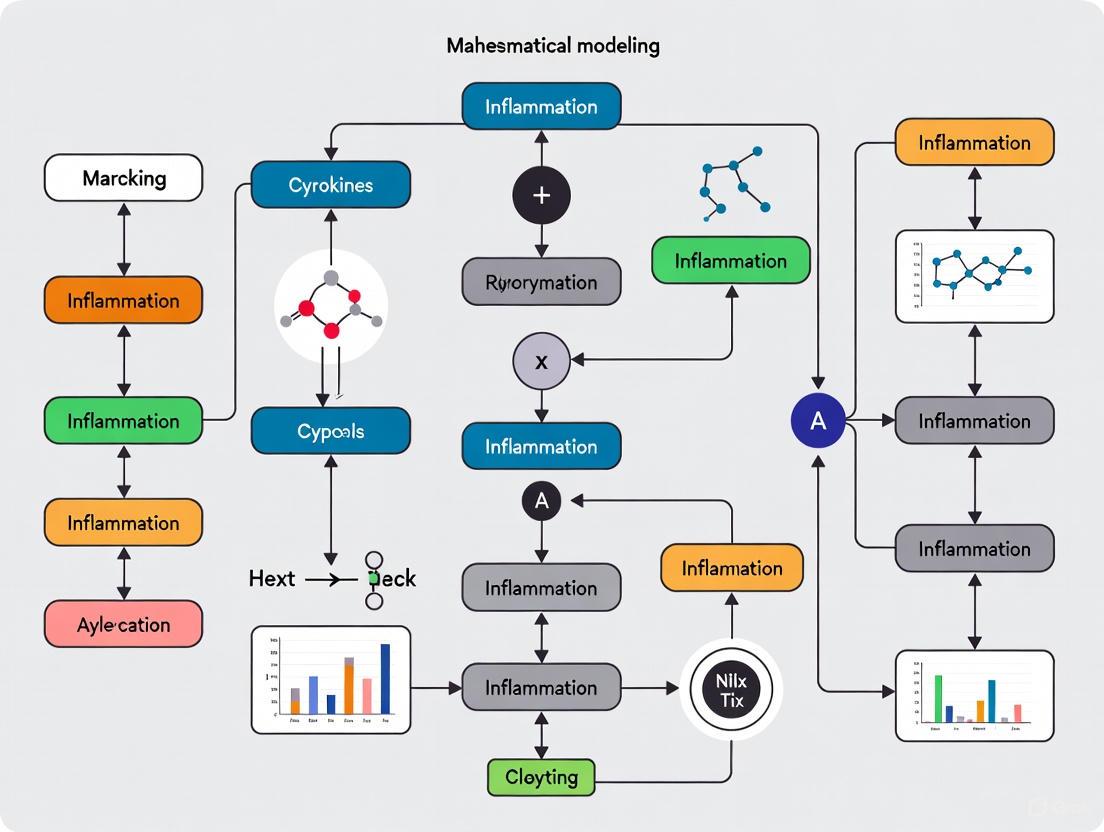

The core interactions between the featured biomarkers, immune cells, and systemic outputs can be conceptualized as a dynamic network. The following diagram illustrates these key regulatory pathways, including both stimulatory and inhibitory relationships.

Figure 1: Inflammatory Biomarker Regulatory Network. Diagram shows the cascade from initial stimulus (LPS) to immune cell activation, cytokine release, and systemic effects, including IL-10's inhibitory feedback.

Formulating a Core ODE Model

Mathematical models often use a system of ODEs to represent the rate of change for each biomarker concentration. The general form for the concentration of a cytokine ( C_i ) can be expressed as:

[ \frac{dC_i}{dt} = \text{Production} - \text{Decay} + \text{Stimulated Release} - \text{Inhibited Release} ]

A simplified, conceptual ODE system for key mediators illustrates these interactions [6]:

[ \begin{align} \frac{d[\text{TNF-α}]}{dt} &= k_{\text{TNF,prod}} \cdot \text{Stimulus} - k_{\text{TNF,decay}} \cdot [\text{TNF-α}] - k_{\text{IL10,inhib}} \cdot [\text{IL-10}] \cdot [\text{TNF-α}] \ \frac{d[\text{IL-6}]}{dt} &= k_{\text{IL6,prod}} \cdot \text{Stimulus} - k_{\text{IL6,decay}} \cdot [\text{IL-6}] - k_{\text{IL10,inhib}} \cdot [\text{IL-10}] \cdot [\text{IL-6}] \ \frac{d[\text{IL-10}]}{dt} &= k_{\text{IL10,prod}} \cdot \text{Stimulus} + k_{\text{IL10,stim}} \cdot [\text{TNF-α}] - k_{\text{IL10,decay}} \cdot [\text{IL-10}] - k_{\text{auto,inhib}} \cdot [\text{IL-10}]^2 \ \frac{d[\text{CRP}]}{dt} &= k_{\text{CRP,prod}} \cdot [\text{IL-6}] - k_{\text{CRP,decay}} \cdot [\text{CRP}] \end{align} ]

Where ( k_{x} ) are rate constants, and "Stimulus" represents an inflammatory trigger like LPS [6]. The term ( k_{\text{auto,inhib}} \cdot [\text{IL-10}]^2 ) represents a negative feedback loop to prevent uncontrolled IL-10 increase [6].

Application: Predicting Nutritional Therapy Response

A secondary analysis of the EFFORT trial utilized mathematical models to demonstrate that high baseline inflammation alters treatment efficacy. Patients with elevated IL-6 (≥11.2 pg/mL) had a 3.5-fold increased 30-day mortality risk (adjusted HR 3.5, 95% CI 1.95–6.28, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the mortality benefit from individualized nutritional therapy was attenuated in these high-inflammatory patients (HR 0.82) compared to those with lower inflammation (HR 0.32) [2]. This quantitative evidence is critical for developing personalized treatment algorithms that stratify patients based on inflammatory status.

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Analysis

Protocol: Quantifying Cytokines in Human Plasma using MSD U-PLEX Assay

This protocol details the measurement of IL-6, TNF-α, and other cytokines from human plasma samples, as employed in recent clinical research [2].

1. Principle The MESO SCALE DISCOVERY (MSD) U-PLEX assay is an electrochemiluminescence-based immunoassay that allows for the multiplexed quantification of multiple cytokines from a single small-volume sample.

2. Key Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytokine Analysis via MSD U-PLEX Assay

| Reagent / Material | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| MSD U-PLEX Assay Kits | Multiplexed capture and detection of specific cytokines. | U-PLEX Human IL-6 Assay; U-PLEX Human TNF-α Assay [2]. |

| MSD Multi-Spot Plates | Solid substrate pre-coated with capture antibodies. | Allows simultaneous measurement of multiple analytes per well [2]. |

| MSD Read Buffer | Triggers electrochemiluminescence reaction. | Contains tripropylamine (TPA) for signal generation. |

| Luminescence Detector | Measures signal intensity for analyte quantification. | MSD MESO QuickPlex SQ 120 or compatible instrument. |

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Thaw EDTA-plasma samples on ice. Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove precipitates. Dilute samples 1:1 with provided diluent [2].

- Step 2: Plate Preparation. Load the U-PLEX linkers coupled with capture antibodies into the desired wells of the MSD Multi-Array plate. Incubate with shaking for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT).

- Step 3: Assay Execution. Add 50 µL of standards or prepared samples to each well. Seal the plate and incubate with shaking for 2 hours at RT. Wash the plate 3 times with PBS-T wash buffer. Add 50 µL of detection antibody solution to each well. Incubate with shaking for 1 hour at RT. Wash 3 times as before.

- Step 4: Signal Detection & Analysis. Add 150 µL of MSD GOLD Read Buffer to each well. Read the plate immediately on an MSD instrument. Calculate cytokine concentrations using a 5-parameter logistic curve fit generated from the standard concentrations.

4. Data Analysis

- Fit a standard curve for each analyte.

- Interpolate sample concentrations from the standard curve.

- Perform quality control checks against known controls.

The workflow for this multiplexed immunoassay is straightforward, as shown in the following protocol diagram.

Figure 2: MSD U-PLEX Assay Workflow. The process involves sequential plate preparation, sample incubation, washing, detection, and signal reading steps.

Protocol: LPS-Induced Experimental Endotoxemia Model

The administration of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to human volunteers is a established model for studying acute inflammatory responses and calibrating mathematical models [6].

1. Principle Intravenous LPS administration activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on innate immune cells, triggering a transient, reproducible cytokine cascade (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10) and clinical symptoms like fever, thereby mimicking acute systemic inflammation.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Subject Screening. Recruit healthy volunteers following strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Obtain informed consent.

- Step 2: LPS Administration. Prepare a certified LPS lot (e.g., E. coli LPS) in sterile, endotoxin-free saline. Administer a standardized dose (e.g., 2 ng/kg body weight) as an intravenous bolus injection.

- Step 3: Blood Sampling. Collect blood via an indwelling catheter at predefined time points: pre-dose (baseline), and at 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240 minutes post-injection. Process plasma immediately and freeze at -80°C for subsequent batch analysis.

- Step 4: Clinical Monitoring. Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, temperature) throughout the experiment.

- Step 5: Data Integration. Measure cytokine levels in the serial plasma samples. Use the time-concentration profiles of cytokines and vital signs to calibrate and validate mathematical models of the inflammatory response [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful research in inflammatory biomarker dynamics requires a suite of specialized reagents, assays, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Inflammatory Biomarker and Modeling Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Product/Assay | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Immunoassays | MSD U-PLEX Assays [2] | Simultaneously quantify multiple cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-10) from low-volume samples with high sensitivity. |

| ELISA Kits | High-Sensitivity CRP ELISA | Precisely measure low concentrations of C-reactive protein in serum/plasma. |

| Inflammatory Stimuli | Ultrapure LPS from E. coli | Standardized trigger for innate immune activation in in vitro cell cultures or in vivo endotoxemia models [6]. |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary Human Monocytes/Macrophages | Ex vivo systems to study cytokine release and signaling pathways in response to stimuli [1]. |

| Computational Tools | MATLAB, R, Python (with SciPy) | Platforms for coding, calibrating, and simulating systems of ODEs for mathematical models [6] [3]. |

| Modeling Software | Copasi, SimBiology | Specialized software for biochemical system modeling and simulation. |

| Biospecimens | Human EDTA-Plasma | Standard sample matrix for clinical biomarker measurement from patients or volunteers [2]. |

The Role of LPS Challenge Studies as a Controlled Model for Human Inflammatory Response

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge studies represent a well-established controlled experimental paradigm for investigating the human inflammatory response in vivo. As the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, LPS acts as a potent agonist for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), initiating a cascade of innate immune signaling events [7]. These studies provide a valuable framework for clinical pharmacology, enabling the characterization of inflammatory pathways and the evaluation of potential anti-inflammatory therapeutics under controlled conditions [7] [8]. Unlike uncontrolled clinical infections, LPS models allow for precise dosing and timing of inflammatory triggers, making them particularly useful for quantifying inflammatory dynamics and validating mathematical models of immune response [6] [8].

The utility of LPS challenges extends across multiple research domains, from basic immunology to drug development. Experimental human endotoxemia involves administering LPS to healthy volunteers either systemically (intravenously) or locally (e.g., intradermally), eliciting a transient, measurable inflammatory response without the ethical concerns associated with inducing actual infection [7] [6]. This approach has proven instrumental in delineating the complex temporal relationships between inflammatory mediators and clinical signs of inflammation, providing critical data for computational modeling efforts aimed at understanding dysregulated immune responses in conditions such as sepsis [6].

LPS Signaling Pathways and Inflammatory Mechanisms

Molecular Recognition and Initial Signaling

The inflammatory response to LPS begins with its recognition by the innate immune system. LPS binding to TLR4 on myeloid cells triggers intracellular signaling through both MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways [7] [9]. The MyD88-dependent pathway leads to rapid activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) [9]. Simultaneously, the TRIF-dependent pathway activates IRF3 and IRF7 transcription factors, driving type I interferon production [9]. This coordinated signaling cascade initiates the clinical and biochemical manifestations of inflammation observed in challenge studies.

Cellular and Cytokine Responses

LPS challenge induces a characteristic cellular response marked by rapid neutrophil influx followed by recruitment of various monocyte subsets and dendritic cells [7]. The cytokine profile is dominated by an acute release of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF, followed by subsequent production of IL-1β, IL-10, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [7]. This carefully orchestrated sequence of immune activation results in a self-limiting inflammatory response that typically resolves within 24-48 hours, making it particularly suitable for controlled experimental settings [7] [10]. The precise temporal pattern of cytokine release provides valuable quantitative data for mathematical modeling of inflammatory dynamics [6] [8].

Quantitative Inflammatory Response Profiles

LPS challenge elicits a consistent, measurable inflammatory response characterized by specific temporal patterns in cytokine production and cellular recruitment. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from human LPS challenge studies.

Table 1: Temporal Cytokine Response Profile to Intradermal LPS Challenge (5 ng dose) [7]

| Cytokine | Peak Concentration Time (hours) | Relative Increase vs. Saline | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | 3-6 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Pro-inflammatory, pyrogenic |

| IL-6 | 6-10 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Pro-inflammatory, induces CRP |

| IL-8 | 6-10 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Neutrophil chemotaxis |

| IL-1β | 10-24 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Pro-inflammatory, pyrogenic |

| IL-10 | 10-24 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Anti-inflammatory feedback |

| IFN-γ | 10-24 | Significant (p<0.0001) | Immune cell activation |

Table 2: Cellular Recruitment Following Intradermal LPS Challenge [7]

| Cell Type | Peak Infiltration Time (hours) | Primary Function in Response |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | 6-10 | First responders, phagocytosis |

| Classical Monocytes (CD14+ CD16-) | 10-24 | Differentiate to macrophages |

| Non-classical Monocytes (CD14+ CD16+) | 10-24 | Patrol functions, cytokine production |

| Dendritic Cells | 10-24 | Antigen presentation, T cell activation |

Table 3: Clinical Signs and Resolution Timeline [7] [6]

| Parameter | Onset (hours) | Peak (hours) | Return to Baseline (hours) | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema | 1-3 | 6-10 | 48 | Multispectral imaging |

| Perfusion | 1-3 | 6-10 | 48 | Laser speckle contrast imaging |

| Temperature | 1-3 | 6-10 | 48 | Thermography |

| Systemic Symptoms (IV LPS) | 1-2 | 3-4 | 6-8 | Clinical assessment |

Experimental Protocols for LPS Challenge Studies

Intradermal LPS Challenge Protocol

The intradermal LPS challenge model provides a localized inflammatory response with minimal systemic effects, making it particularly suitable for proof-of-pharmacology studies of anti-inflammatory compounds [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- LPS from Escherichia coli, serotype O55:B5 (Sigma Chemicals)

- Sterile saline (0.9% sodium chloride)

- Tuberculin syringes (1 mL) with 27-30 gauge needles

- Multispectral imaging system (Antera 3D, Miravex)

- Laser speckle contrast imager (PeriCam PSI System, Perimed)

- Thermography camera (FLIR X6540sc)

- Biopsy punch (3 mm)

- Suction blister device

Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Healthy male volunteers (18-45 years) after overnight fast. Exclusion criteria include immune disorders, recent infections, or medication use.

- LPS Administration: Prepare LPS solution at concentration of 5 ng/50 μL saline. Administer intradermally to volar forearm using 2-4 injections per subject with saline control.

- Non-invasive Assessments:

- Record baseline measurements before injection

- Assess erythema, perfusion, and skin temperature at 3, 6, 10, 24, and 48 hours post-administration

- Standardize imaging conditions and subject positioning

- Invasive Sampling:

- Suction Blisters: Induce over injection site at predetermined time points

- Biopsy Collection: Obtain 3-mm punch biopsies from injection sites

- Sample Processing:

- Collect blister exudate in sodium citrate/PBS solution

- Centrifuge at 2000g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Aliquot supernatant for cytokine analysis (Meso Scale Discovery)

- Process cell pellet for flow cytometry with antibody panel

Intravenous LPS Challenge Protocol

Intravenous administration models systemic inflammation and enables correlation of cytokine dynamics with clinical signs [11] [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- LPS (NIH Clinical Center Reference Endotoxin)

- Normal saline for injection

- Emergency equipment for anaphylaxis

- Intravenous catheter

- Blood collection tubes (EDTA, heparin, serum)

Procedure:

- Pre-study Screening: Comprehensive medical evaluation and laboratory tests

- LPS Preparation: Reconstitute according to manufacturer instructions, verify endotoxin content

- Administration: Inject 2 ng/kg body weight LPS as intravenous bolus

- Monitoring: Continuous vital sign monitoring for 6 hours, hourly for 8 hours, then regularly until 24 hours

- Blood Sampling: Collect at baseline, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours post-administration

- Clinical Assessment: Document symptoms using standardized scales

Mathematical Modeling of Inflammatory Dynamics

Modeling Approaches for LPS Challenge Data

Mathematical modeling of LPS-induced inflammatory dynamics enables quantitative prediction of host response and facilitates drug development. Several modeling frameworks have been successfully applied to LPS challenge data:

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models: A recently developed multiscale ODE model comprises 15 equations describing processes at both cellular and organism levels [6]. This model simulates immune cell activation, cytokine release (TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β), and clinical signs including body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure. The model structure incorporates negative feedback loops, particularly the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression by IL-10, representing important regulatory mechanisms [6].

Delay Differential Equation (DDE) Models: DDE frameworks effectively capture delayed biomarker responses in LPS challenges [8]. These models estimate time delays for cytokine secretion (TNF-α: 0.924h, IL-6: 1.46h, IL-8: 1.48h) and CRP response relative to IL-6 (4.2h delay) [8]. The LPS kinetics are described by a one-compartment model with first-order elimination, with estimated clearance of 35.7 L/h and volume of distribution of 6.35 L [8].

Parameter Identification: Sensitivity analysis has identified six key parameters for model calibration: three compounded scaling parameters (sTNF, sIL6, sIL10) and three mRNA half-life parameters (kTNFmRNA, kIL6mRNA, kIL10mRNA) [6]. Profile likelihood analysis confirms these parameters are uniquely identifiable using calibration data [6].

Integration with Experimental Data

Mathematical models are calibrated using both in vitro and in vivo data, enabling simulation of both acute bolus and prolonged LPS exposures [6]. The models can replicate the dose-response behavior across different LPS administration protocols and have been validated against human experimental endotoxemia data [6] [8]. This integration allows for prediction of cytokine dynamics and correlation with clinical signs, providing a valuable tool for designing and interpreting LPS challenge studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for LPS Challenge Studies

| Reagent/Assay | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| LPS Source | E. coli O55:B5 (Sigma) | TLR4-specific ligand for controlled inflammation |

| Cytokine Analysis | Meso Scale Discovery Multi-array | Multiplex quantification of TNF, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IFN-γ |

| Flow Cytometry Panel | CD14, CD16, CD66b, HLA-DR, CD4, CD8, CD56, CD19, CD20 | Immune cell phenotyping and quantification |

| LAL Assay | QCL-1000 kit (Lonza) | Determination of LPS biological activity |

| LC/MS/MS | 3-hydroxymyristate quantitation | Direct measurement of LPS mass in biological samples |

| Imaging Systems | Antera 3D (Miravex), PeriCam PSI (Perimed), FLIR X6540sc | Non-invasive assessment of local inflammatory signs |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

LPS challenge models serve multiple critical functions in pharmaceutical research and development:

Proof-of-Pharmacology Studies: Intradermal LPS challenge provides a robust platform for demonstrating target engagement and pharmacological activity of anti-inflammatory compounds [7]. The localized nature of the response allows for simultaneous testing of multiple compounds or doses in a single subject, with saline and untreated sites serving as internal controls.

TLR4-Focused Drug Development: Unlike broader inflammatory stimuli such as UV-killed E. coli, LPS specifically activates the TLR4 pathway, enabling precise evaluation of TLR4-targeted therapeutics [7]. This specificity is particularly valuable for mechanism-of-action studies.

Biomarker Validation: LPS challenges facilitate the qualification of novel inflammatory biomarkers, including cellular populations, cytokine profiles, and imaging endpoints [7] [12]. The well-characterized temporal response patterns enable assessment of biomarker kinetics and dynamic range.

Cross-Species Translation: Quantitative modeling of LPS responses supports translation between preclinical models and human subjects [8]. Model-based interspecies extrapolation helps bridge efficacy assessments from animal studies to human trials.

Limitations and Considerations

While LPS challenge models offer significant advantages, several important limitations warrant consideration:

Model Specificity: The TLR4-focused response may not fully capture inflammation mediated through other pathways relevant to specific disease contexts [7].

Temporal Dynamics: Bolus LPS administration generates acute, transient inflammation that differs from the prolonged exposure typical of natural infections [6]. Continuous infusion models address this limitation but are more complex to implement.

Immunological Reprogramming: Repeated LPS exposure induces tolerance or altered responses in both systemic and central nervous system immunity [11] [9]. This phenomenon necessitates careful consideration in study designs involving multiple challenges.

Individual Variability: Despite standardized protocols, inter-individual differences in LPS response occur, requiring appropriate sample sizes and stratification in clinical studies [8].

LPS challenge studies provide a controlled, reproducible model for investigating human inflammatory responses and their mathematical modeling. The standardized protocols, quantitative response data, and well-characterized kinetics make this approach particularly valuable for drug development and translational immunology research. Integration of experimental LPS data with computational modeling frameworks continues to enhance our understanding of inflammatory dynamics and supports the development of novel therapeutic strategies for inflammatory disorders.

Defining Compartmental and Indirect Response (IDR) Modeling Frameworks

Mathematical modeling of biological processes is indispensable in pharmacological research and drug development. Compartmental modeling provides a framework for characterizing the time-course of substances as they distribute between physiological compartments, while Indirect Response (IDR) modeling specifically describes delayed pharmacological effects mediated through the inhibition or stimulation of underlying physiological processes. These modeling frameworks are particularly powerful for analyzing the dynamics of inflammatory markers, a critical aspect of understanding sepsis, immune responses, and related therapeutic interventions [13] [14]. This note delineates the theoretical foundations of these frameworks, provides protocols for their application in inflammatory research, and visualizes their core structures and workflows.

Theoretical Foundations

Core Principles of Indirect Response (IDR) Models

IDR models are applied when a time lag exists between plasma drug concentrations and the observed pharmacological response, not due to distributional delays, but because the drug acts by inhibiting or stimulating the production or loss of factors controlling the measured response [13]. The foundational IDR structure describes the turnover of a response variable ( R ):

[ \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} - k{out} \cdot R ]

At steady state (baseline, with no drug present), ( R0 = k{in} / k{out} ) [13] [15]. Drug effects are introduced by modulating ( k{in} ) or ( k_{out} ) via inhibitory or stimulatory functions, leading to four basic model variants.

Table 1: The Four Basic Indirect Response (IDR) Models [13]

| Model | Drug Action Mechanism | Differential Equation | Typical Response Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Inhibition of production | ( \displaystyle \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} \cdot \left(1 - \frac{I{max} \cdot Cp}{IC{50} + Cp}\right) - k{out} \cdot R ) | Response decreases, then returns to baseline |

| Model II | Inhibition of loss | ( \displaystyle \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} - k{out} \cdot \left(1 - \frac{I{max} \cdot Cp}{IC{50} + Cp}\right) \cdot R ) | Response increases, then returns to baseline |

| Model III | Stimulation of production | ( \displaystyle \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} \cdot \left(1 + \frac{S{max} \cdot Cp}{SC{50} + Cp}\right) - k{out} \cdot R ) | Response increases, then returns to baseline |

| Model IV | Stimulation of loss | ( \displaystyle \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} - k{out} \cdot \left(1 + \frac{S{max} \cdot Cp}{SC{50} + Cp}\right) \cdot R ) | Response decreases, then returns to baseline |

- ( Cp ): Plasma drug concentration; ( I{max} ): Max. fractional inhibition (0–1); ( S{max} ): Max. stimulation factor (≥0); ( IC{50}/SC_{50} ): Conc. for 50% effect.

Figure 1: Fundamental Structure of an Indirect Response Model. The drug modulates the production or dissipation of the response variable, introducing a mechanistic delay.

A key characteristic of IDR models is that the time of maximum response ((t{Rmax})) shifts with dose, occurring later as the dose increases. This contrasts with effect-compartment models, where (t{Rmax}) remains constant, providing a critical tool for discriminating between mechanisms [16].

Compartmental Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling

Compartmental models describe the body as a series of interconnected compartments where a drug distributes and is eliminated. A one-compartment model with intravenous bolus administration is often sufficient for initial PK/PD linking, described by:

[ C_p(t) = \frac{Dose}{V} \cdot e^{-(CL/V) \cdot t} ]

where ( C_p(t) ) is plasma concentration at time ( t ), ( V ) is volume of distribution, and ( CL ) is clearance [13] [14]. More complex multi-compartment or non-linear models are used when the pharmacokinetics require it. The output of the PK model serves as the input driving the pharmacodynamic response in the IDR model.

Application to Inflammatory Marker Dynamics

The host inflammatory response to infection or challenge involves complex, dynamic interactions between mediators, making it an ideal application for IDR modeling. The controlled setting of a human endotoxemia study, where lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is administered to healthy volunteers, provides high-quality data for model development [6] [14].

Modeling Cytokine and CRP Dynamics

Quantitative models have been developed to characterize inflammatory biomarkers like TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and CRP in response to LPS. The relationship between LPS and cytokine dynamics can be captured by an IDR model with a delayed, concentration-dependent stimulation of production [14]:

[ \frac{dC{cytokine}}{dt} = k{in} \cdot \left(1 + S{LPS} \cdot C{LPS}(t - \tau)\right) - k{out} \cdot C{cytokine} ]

Here, ( S_{LPS} ) is a stimulatory function, and ( \tau ) is a delay time accounting for the lag between LPS exposure and cytokine release [14]. Similarly, CRP production is stimulated by IL-6, also with an associated delay [14].

Table 2: Example Model Parameters for Inflammatory Biomarkers from Human Endotoxemia Studies [14]

| Biomarker | Stimulus | Baseline (R₀) | Estimated Delay (τ, h) | Half-life (t₁/₂, h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | LPS | At steady state | 0.92 | Derived from kout |

| IL-6 | LPS | At steady state | 1.46 | Derived from kout |

| IL-8 | LPS | At steady state | 1.48 | Derived from kout |

| CRP | IL-6 | At steady state | 4.2 | ~19 h (from literature) |

Figure 2: Inflammatory Signaling and Feedback. LPS activates immune cells, leading to transcription and translation of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, which cause clinical signs. Anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 provide negative feedback.

Experimental Protocol: IDR Model Development for an Inflammatory Inhibitor

This protocol details the steps for developing a PK/IDR model to characterize a novel drug candidate designed to inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α release.

Study Design and Data Collection

Materials:

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS): E. coli O:113 standard for inflammatory challenge.

- Investigational Drug: Small molecule inhibitor of TNF-α production.

- Healthy Volunteers: Adults aged 18-50, following ethical approval.

- LC-MS/MS System: For quantitation of plasma drug concentrations.

- ELISA Kits: High-sensitivity for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10.

- Modeling Software: NONMEM, Monolix, or similar PK/PD software with ODE/DDE solving capability.

Procedure:

- Pre-Study Baseline: Obtain a minimum of three baseline measurements of inflammatory biomarkers (TNF-α, IL-6) prior to any drug/LPS administration to establish a reliable ( R_0 ) [15].

- Pharmacokinetic Phase:

- Administer the investigational drug intravenously or orally according to the study design.

- Collect dense serial blood samples for drug assay (e.g., pre-dose, 5, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 h post-dose).

- Inflammatory Challenge & Pharmacodynamic Phase:

- Administer a standardized intravenous LPS bolus (e.g., 2 ng/kg) at a predetermined time post-drug dose (e.g., 1 h) [14].

- Collect serial blood samples for biomarker analysis (e.g., pre-LPS, 30, 60, 90 min, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 h post-LPS).

- Data Preparation: Combine plasma drug concentration-time data and biomarker time-course data into a single dataset for PK/PD analysis.

Model Development Workflow

Figure 3: PK/IDR Model Development Workflow. A stepwise approach for building an integrated model.

- Develop Base Pharmacokinetic Model: Fit the plasma concentration-time data to determine structural PK model (e.g., 1- or 2-compartment) and estimate parameters (CL, V). This provides the ( C_p(t) ) driver for the PD model [14].

- Select Preliminary IDR Model Structure: Based on the drug's known mechanism (inhibition of TNF-α production), start with IDR Model I. The differential equation is: [ \frac{dR}{dt} = k{in} \cdot \left(1 - \frac{I{max} \cdot Cp}{IC{50} + Cp}\right) - k{out} \cdot R ]

- Handle Baseline Response: The initial condition ( R(0) = R_0 ) can be fixed to the average pre-dose baseline measurement or estimated as a parameter. For data normalized to baseline, the modified differential equations must be used to avoid biased parameter estimates [15].

- Incorporate a Delay Mechanism: If the TNF-α response lag after LPS is not fully captured, introduce a Delay Differential Equation (DDE), where the stimulatory effect of LPS on ( k_{in} ) is a function of ( LPS(t - \tau) ) [14].

- Parameter Estimation: Simultaneously fit the PK and IDR models to the concentration and TNF-α time-course data using an appropriate estimation algorithm (e.g., SAEM in NONMEM) to obtain final parameter estimates (( k{in}, k{out}, I{max}, IC{50}, \tau )).

- Model Validation: Validate the final model using techniques like visual predictive checks or bootstrap analysis to ensure it robustly captures the observed data and provides reliable simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for IDR Modeling in Inflammation

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Standardized inflammatory challenge; TLR4 agonist. | Inducing a controlled, transient inflammatory response in human endotoxemia studies [14]. |

| Multiplex Cytokine ELISA | Quantifies multiple cytokine proteins simultaneously from a single sample. | Generating high-density time-course data for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 for model fitting [6]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Gold-standard for bioanalysis; quantifies drug concentrations in biological matrices. | Determining the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of the investigational drug [14]. |

| NONMEM | Industry-standard software for non-linear mixed effects modeling. | Developing population PK/PD models and estimating parameters with inter-individual variability [14]. |

| Monolix | User-friendly software for non-linear mixed effects modeling. | An alternative to NONMEM for PK/PD model development and parameter estimation. |

| PEtab Format | Standardized format for specifying parameter estimation problems. | Ensuring model, data, and optimization problem reproducibility and reusability [17]. |

{ document }

Capturing Temporal Dynamics: The Importance of Time Delays and Biomarker Half-Lives

The accurate prediction of inflammatory disease progression and treatment response relies on a fundamental understanding of temporal dynamics, particularly the time delays inherent in biological systems and the half-lives of key molecular biomarkers. This application note details the critical importance of integrating these temporal parameters into mathematical models of inflammation. We provide a comprehensive reference of quantitative kinetic data for major inflammatory biomarkers and present detailed experimental protocols for quantifying these dynamics in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we illustrate the application of these data in constructing ordinary differential equation (ODE) models capable of simulating both acute and prolonged inflammatory responses, supported by ready-to-use diagrammatic representations of model structures and workflows. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the methodological tools to enhance the predictive power of their computational models in inflammation research.

Inflammatory responses are not instantaneous; they unfold over time through a complex sequence of molecular and cellular events characterized by inherent time delays and differential persistence of signaling molecules. The failure to account for these temporal dynamics represents a significant limitation in many traditional models, reducing their predictive accuracy for real-world clinical scenarios such as sepsis or chronic inflammatory diseases [6]. Time delays arise from multi-stage processes, such as the transcription of messenger RNA (mRNA) and the subsequent translation of proteins following an inflammatory stimulus. Biomarker half-lives—the time required for the concentration of a substance to reduce by half—determine the duration of a molecule's biological activity and shape the overall temporal profile of the inflammatory response.

Mechanism-based mathematical modeling, particularly using ODEs, provides a powerful framework for integrating these kinetic parameters. However, the development of such models is often hampered by a lack of consolidated, quantitative data and standardized methods for parameter estimation. This document addresses this gap by synthesizing critical data and methodologies. We focus on a clinically validated, multiscale ODE model of the human inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [6], which effectively captures responses to both acute bolus injections and prolonged LPS infusions, and bridges cellular-level events with organism-level vital signs. The following sections provide the essential data and protocols to implement and adapt such models for a variety of research applications.

Quantitative Dynamics of Key Inflammatory Biomarkers

Incorporating accurate kinetic parameters is the first step in building a physiologically realistic model of inflammation. The table below summarizes the half-lives of critical molecular species as utilized in a foundational human inflammatory response model [6].

Table 1: Half-Lives of Key Inflammatory Biomarkers and mRNA Species

| Molecular Species | Reported Half-Life | Biological Role & Modeling Significance |

|---|---|---|

| TNF mRNA | 0.25 hours [6] | A pro-inflammatory cytokine; short mRNA half-life enables rapid response termination and tight control of protein production. |

| IL-6 mRNA | 1.00 hour [6] | A pro-inflammatory cytokine and key driver of acute phase response; half-life influences the peak and decline of IL-6 serum levels. |

| IL-10 mRNA | 1.50 hours [6] | A critical anti-inflammatory cytokine; longer half-life supports sustained production for effective negative feedback on pro-inflammatory signals. |

| TNF Protein | 0.50 hours [6] | Short protein half-life confines TNF signaling to a localized and brief timeframe, preventing uncontrolled systemic inflammation. |

| IL-6 Protein | 2.25 hours [6] | Longer half-life than TNF allows IL-6 to act as a systemic messenger, coordinating distant organ responses like fever and hepatic CRP production. |

| IL-10 Protein | 1.00 hour [6] | Half-life balances its role in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines without completely shutting down the necessary immune response. |

These half-life values are crucial for setting the rate constants in ODE models. For instance, the degradation rate constant ((k{deg})) in a model can be calculated from the half-life ((t{1/2})) using the formula: (k{deg} = \frac{\ln(2)}{t{1/2}}). The inclusion of mRNA dynamics, with their distinct and often shorter half-lives, introduces a necessary time delay between immune cell activation and the appearance of mature cytokines in the plasma, significantly improving the model's dynamical behavior [6].

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

Protocol: Estimating mRNA and Protein Half-LivesIn Vitro

This protocol outlines a standard method for determining the half-lives of inflammatory mediators using in vitro cell stimulation systems, forming the basis for parameter estimation in computational models [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for In Vitro Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A potent pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) used to stimulate a robust and synchronized inflammatory response in immune cells. |

| Primary Immune Cells or Cell Lines | Biological substrate; primary human monocytes or macrophages are preferred for their physiological relevance. |

| Transcription Inhibitor (e.g., Actinomycin D) | Halts all novel RNA transcription, allowing researchers to track the decay of existing mRNA pools over time. |

| Protein Synthesis Inhibitor (e.g., Cycloheximide) | Halts novel protein translation, allowing for the measurement of protein stability and decay independent of new synthesis. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality total RNA from cell cultures for subsequent quantitative analysis. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Assay | Quantifies the abundance of specific mRNA transcripts (e.g., TNF, IL-6, IL-10) using reverse transcription and fluorescent probes. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Measures the concentration of specific cytokine proteins (e.g., TNF, IL-6) in cell culture supernatants. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cell Stimulation: Seed primary human immune cells (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells or purified monocytes) in culture plates and stimulate them with a defined concentration of LPS (e.g., 10-100 ng/mL) to induce inflammatory gene expression.

- Inhibitor Addition: After a predetermined stimulation period (e.g., 2-4 hours), add a transcription inhibitor (Actinomycin D) or a translation inhibitor (Cycloheximide) to the culture medium.

- Time-Point Sampling: Immediately before inhibitor addition (t=0) and at multiple sequential time points thereafter (e.g., 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 hours), collect cell samples.

- For mRNA half-life: Collect cell pellets for RNA extraction and qPCR analysis.

- For protein half-life: Collect cell culture supernatants for ELISA analysis.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- For mRNA, use qPCR to determine the relative quantity of the target mRNA at each time point. Normalize data to a housekeeping gene.

- For protein, use ELISA to determine the cytokine concentration at each time point.

- Data Fitting & Calculation: Plot the natural logarithm of the concentration (or relative quantity) against time. The data should approximate a straight line. The half-life is calculated from the slope of the line of best fit ((k)) using the equation: (t_{1/2} = \frac{\ln(2)}{k}).

Protocol: Validating Dynamics via Human Experimental Endotoxemia

In vitro parameters require validation in a whole-organism context. The human experimental endotoxemia model provides a controlled setting for this purpose [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Purified LPS: Licensed for human administration.

- Clinical Grade Sampling Kits: For serial blood collection.

- High-Sensitivity Immunoassays: For quantifying low serum levels of cytokines (e.g., high-sensitivity ELISA or multiplex platforms like Olink PEA [18]).

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Subject Administration: Healthy human volunteers receive an intravenous bolus or continuous infusion of a standardized, low dose of LPS.

- Serial Blood Collection: Blood samples are drawn at baseline and frequently after LPS administration (e.g., every 30-60 minutes for the first 4-8 hours, then at longer intervals up to 24 hours).

- Biomarker Quantification: Serum or plasma is analyzed for a panel of inflammatory biomarkers, including cytokines (TNF, IL-6, IL-10), clinical markers like C-reactive protein (CRP), and physiological variables like core body temperature.

- Model Calibration: The time-series data obtained is used to calibrate the ODE model. Parameters, particularly those for mRNA and protein half-lives as well as production rates, are adjusted within biologically plausible ranges to achieve the best possible fit between the model output and the experimental data. This process ensures the model accurately reflects in vivo human physiology.

Mathematical Modeling: From Data to Dynamic Models

The kinetic data gathered from the aforementioned protocols can be integrated into a system of ODEs. A general form for the rate of change of each cytokine concentration can be expressed as:

[\frac{d[Protein]}{dt} = k{translation} \cdot [mRNA] - k{deg_protein} \cdot [Protein]]

Where (k_{deg_protein}) is derived directly from the protein's half-life. Similarly, the equation for its corresponding mRNA is:

[\frac{d[mRNA]}{dt} = k{transcription} \cdot (Stimulus) - k{deg_mRNA} \cdot [mRNA]]

Here, (k_{deg_mRNA}) is derived from the mRNA half-life, and the "Stimulus" term often includes the inhibitory effect of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, creating a negative feedback loop that is essential for model stability and biological fidelity [6]. This core structure can be scaled to simulate a full inflammatory network.

Diagram 1: Inflammatory Network with Half-Lives.

Application Note: Implementing a Clinically Validated Inflammatory Response Model

This section provides a concrete example of how to implement the principles and data described above, based on a published model that simulates the human inflammatory response to LPS [6].

Background: The model is a 15-equation ODE system that integrates cellular activation, mRNA dynamics, cytokine production, and physiological responses. Its key advantage is the ability to simulate both acute and prolonged inflammatory stimuli without becoming unstable, making it suitable for studying real infections.

Key Features and Workflow:

Diagram 2: Model Implementation Workflow.

Implementation Steps:

- Define Model Scope: Determine the key components to be modeled (e.g., specific cytokines, cell types, physiological outputs).

- Formulate Equations: Write a system of ODEs based on the structure in Section 4. Explicitly include terms for production, degradation (using rate constants from Table 1), and regulatory interactions (e.g., IL-10 inhibition).

- Set Initial Conditions: Define the baseline (pre-stimulus) state for all variables, typically a state of homeostasis.

- Parameter Estimation: Use the half-lives from Table 1 to fix degradation parameters. Calibrate other unknown parameters (e.g., production rates) against experimental data [6] using optimization algorithms.

- Simulation and Validation: Solve the ODE system numerically. Validate the model by comparing its output against independent datasets not used for calibration, such as data from prolonged LPS infusions or different patient cohorts [19] [18].

The conscious integration of temporal dynamics—specifically time delays and biomarker half-lives—is a prerequisite for developing mathematical models that are not just descriptive but truly predictive of inflammatory disease trajectories. The quantitative data, experimental protocols, and model implementation framework provided in this application note offer a foundational toolkit for researchers. By adopting these principles, scientists can enhance the physiological relevance of their models, thereby improving their utility in drug development, biomarker discovery, and the creation of digital patient twins for personalized medicine. Future efforts should focus on expanding the library of kinetic parameters for a wider range of biomarkers and patient populations to further refine these powerful computational tools.

In the realm of inflammatory marker dynamics research, quantitative modeling serves as a foundational pillar for transforming complex biological observations into predictive, actionable knowledge. Mathematical modeling is defined as the process of creating mathematical representations of systems' input/output behaviors, often involving the analysis of interacting parts within a system [20]. In the specific context of inflammatory responses, these models provide a structured framework to characterize biological variability and optimize experimental design, ultimately accelerating therapeutic development for inflammatory conditions including sepsis, metabolic diseases, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

The critical importance of quantitative modeling is particularly evident in sepsis research, where dysregulated inflammatory responses contribute significantly to global mortality, accounting for approximately 20% of all deaths worldwide [6]. Through sophisticated mathematical representations, researchers can decipher the complex interplay between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, predict patient-specific responses to interventions, and design more efficient clinical studies. This application note delineates specific protocols and methodologies for employing quantitative models to characterize biological variability and inform study design in inflammatory marker research.

Key Objectives and Their Applications

Characterizing Biological Variability

Quantitative models excel at capturing and explaining the substantial heterogeneity observed in inflammatory responses across individuals and experimental conditions. By developing mathematical representations that account for diverse sources of variability, researchers can move beyond simple averages to understand the full spectrum of biological responses.

In recent investigations of Malnutrition-Inflammation-Atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome in dialysis patients, mathematical approaches were essential for characterizing variability in inflammatory marker dynamics [21]. Researchers collected longitudinal data on C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) at multiple time points (baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months), revealing significant inter-individual variability in both baseline levels and trajectory of change [21]. Quantitative models successfully captured this heterogeneity by incorporating patient-specific factors including dialysis modality, nutritional status, and comorbidities.

Similarly, in the development of a mechanistic mathematical model of the inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure, researchers implemented parameter sensitivity and identifiability analyses to determine which biological parameters contributed most significantly to variability in system outputs [6]. This approach identified six key parameters (including three compounded scaling parameters and three mRNA half-life parameters) that primarily drove variability in cytokine production dynamics, enabling more focused characterization of inter-individual differences in inflammatory responsiveness [6].

Informing Study Design

Quantitative models provide powerful tools for optimizing experimental protocols and clinical trial designs in inflammatory research. Through in silico simulations, researchers can evaluate different sampling strategies, intervention timing, and endpoint selection before conducting costly empirical studies.

In the feasibility analysis of composite inflammatory biomarkers across multiple energy restriction trials, quantitative modeling informed study design by identifying optimal biomarker combinations and sampling protocols [22]. Researchers developed and compared four composite biomarker models with varying constituents and complexity, determining that extended, endothelial, and optimized composite biomarkers (incorporating multiple inflammatory markers beyond the minimal set) provided superior sensitivity for detecting intervention effects compared to simpler models [22]. This modeling approach directly informed the design of subsequent nutritional intervention studies by specifying which biomarkers to measure and when to measure them to maximize detection of treatment effects.

For studies of acute inflammatory responses, mathematical models have been employed to optimize challenge tests and sampling schedules. In the PhenFlex Challenge Test (PFT) used to assess inflammatory resilience, modeling of postprandial inflammatory marker responses informed the timing of blood sample collection at t = 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes after challenge administration [22]. This optimized schedule captured the dynamic response trajectory while minimizing the number of samples required, reducing participant burden and analytical costs.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Inflammatory Marker Dynamics from Recent Studies

| Study Focus | Inflammatory Markers Measured | Key Quantitative Findings | Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIA Syndrome in Dialysis Patients [21] | CRP, IL-6, TNF-α | High-inflammation patients had higher MIA scores (8.7 ± 2.1 vs. 6.4 ± 1.9, P < 0.001); CRP correlated negatively with albumin (r = -0.41) and positively with carotid intima-media thickness (r = 0.36) | Multivariate regression and Cox models |

| Inflammatory Response to LPS [6] | TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β | Model calibrated using 6 key parameters; System captured both acute (bolus) and prolonged (infusion) LPS exposure scenarios | Ordinary differential equations (15 equations, 48 parameters) |

| Composite Biomarker Feasibility [22] | IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, MPO, CRP, SAA | Minimal composite biomarkers (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α) lacked detection ability; Extended models showed significant responses to energy restriction (P < 0.005) | Health space modeling with multiple configurations |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Longitudinal Inflammatory Marker Assessment

Purpose: To collect longitudinal data on inflammatory marker dynamics for quantitative model development and validation in chronic inflammatory conditions.

Materials:

- EDTA plasma collection tubes

- High-sensitivity cytokine detection platforms (e.g., Meso Scale Discovery multiplex immunoassays)

- -80°C freezer for sample storage

- Clinical data collection forms electronic health record access

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll study participants meeting specific inflammatory condition criteria (e.g., dialysis patients for MIA syndrome, obese individuals for metabolic inflammation)

- Baseline Assessment: Collect comprehensive clinical data including demographics, medical history, medication use, and body composition measurements

- Blood Sample Collection: Draw blood samples at predetermined intervals (baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months) following standardized protocols [21]

- Sample Processing: Process blood samples within 2 hours of collection through centrifugation, aliquoting, and storage at -80°C

- Inflammatory Marker Quantification: Analyze samples using validated immunoassays for key inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, etc.) in batch analyses to minimize inter-assay variability

- Data Integration: Combine inflammatory marker data with clinical outcomes for model development

Quality Control:

- Implement standardized sampling protocols across all study sites

- Use uniform sample processing procedures with strict adherence to time limits

- Include quality control samples in each analytical batch

- Perform blinded duplicate measurements for a subset of samples

Protocol for Inflammatory Challenge Studies

Purpose: To characterize dynamic inflammatory responses to standardized challenges for resilience biomarker development.

Materials:

- PhenFlex Challenge Test (PFT) composition: 75g glucose, 60g fat, 18g protein concentrate [22]

- Multiplex immunoassay platforms capable of measuring multiple cytokines simultaneously

- Timed sample collection equipment

- Clinical monitoring equipment for vital signs

Procedure:

- Pre-Challenge Preparation: Instruct participants to fast for at least 12 hours overnight before the challenge test

- Baseline Sampling: Collect baseline blood samples (t=0) and measure vital signs

- Challenge Administration: Administer standardized PFT drink within 5 minutes under supervision

- Post-Challenge Monitoring: Collect additional blood samples at predetermined time points (t=30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes) [22]

- Clinical Monitoring: Assess vital signs and symptom development throughout the testing period

- Sample Analysis: Measure inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, etc.) using multiplexed immunoassays

- Data Modeling: Calculate composite inflammatory resilience scores using health space modeling approaches

Safety Considerations:

- Obtain ethical approval and informed consent

- Have emergency medications and equipment available

- Exclude participants with contraindications to high-fat challenges

- Monitor for adverse events throughout the procedure

Protocol for Mathematical Model Development and Calibration

Purpose: To develop and calibrate mechanistic mathematical models of inflammatory dynamics.

Materials:

- Computational software for mathematical modeling (MATLAB, R, or Python with appropriate libraries)

- Experimental data for model calibration (from Protocols 3.1 and 3.2)

- High-performance computing resources for complex model simulations

Procedure:

- Model Structure Design: Develop ordinary differential equation models representing key inflammatory pathways based on established biology [6]

- Parameter Identification: Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs

- Model Calibration: Estimate parameter values using experimental data through optimization algorithms

- Identifiability Analysis: Perform profile likelihood analysis to confirm parameters are uniquely identifiable [6]

- Model Validation: Test calibrated models against independent datasets not used in calibration

- Model Application: Use validated models to simulate experimental scenarios and inform study design

Analytical Steps:

- Implement local sensitivity analysis using partial derivatives or direct differential method

- Apply optimization algorithms (e.g., maximum likelihood, Bayesian estimation) for parameter estimation

- Conduct profile likelihood analysis for identifiability assessment

- Perform uncertainty analysis through Monte Carlo methods

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Inflammatory Marker Dynamics Research

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Research Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Immunoassay Panels | Meso Scale Discovery Multiplex Panel Human | Simultaneous quantification of multiple inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, etc.) | Measuring inflammatory mediator responses to challenge tests [22] |

| PhenFlex Challenge Test (PFT) | 75g glucose, 60g fat, 18g protein concentrate | Standardized high-caloric liquid meal challenge for assessing phenotypic flexibility | Evaluating inflammatory resilience in nutritional interventions [22] |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Purified bacterial endotoxin | Experimental inflammatory stimulus for modeling inflammatory responses | Human endotoxemia studies for model calibration [6] |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | MATLAB, R, Python with ODE solvers | Development and simulation of mechanistic models of inflammatory dynamics | Creating ODE models of cytokine responses to LPS [6] |

| Sample Collection System | EDTA plasma tubes, -80°C storage | Standardized biological sample collection and preservation | Longitudinal studies of inflammatory markers [21] |

Visualization of Modeling Workflows

Inflammatory Dynamics Modeling Workflow

Inflammatory Dynamics Modeling Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential process for developing and applying quantitative models of inflammatory marker dynamics, from data collection through to study design applications.

Inflammatory Signaling Pathway Model

Inflammatory Signaling Pathway Model - This diagram represents the key components and interactions in a mechanistic mathematical model of inflammatory signaling, highlighting the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory feedback mechanisms.

Quantitative modeling provides an indispensable framework for characterizing variability and informing study design in inflammatory marker research. Through the application of mechanistic mathematical models, researchers can capture the essential dynamics of inflammatory processes, account for biological heterogeneity, and optimize experimental approaches. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note offer practical guidance for implementing these approaches in both basic and translational research settings.

As the field advances, the integration of quantitative modeling across all stages of research—from initial experimental design to clinical application—will be essential for unlocking deeper insights into inflammatory processes and developing more effective therapeutic strategies for inflammatory conditions. The continued refinement of these modeling approaches promises to enhance both the efficiency and predictive power of inflammatory marker research, ultimately accelerating progress toward improved clinical outcomes.

Methodological Approaches and Translational Applications in Inflammation Research

Mathematical modeling has become an indispensable tool in biomedical research, providing a quantitative framework to understand the complex dynamics of biological systems. In the specific context of inflammatory marker dynamics, these models enable researchers to simulate the nonlinear interactions between cytokines, immune cells, and physiological responses that characterize conditions such as sepsis, autoimmune diseases, and chronic inflammation [6] [23]. The ability to computationally represent these processes allows for hypothesis testing, prediction of therapeutic outcomes, and identification of key regulatory mechanisms that might not be apparent through experimental approaches alone.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of three fundamental modeling frameworks used in inflammation research: Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), Delay Differential Equations (DDEs), and Hybrid Multi-Scale Models. We focus on their practical application in simulating inflammatory marker dynamics, with detailed protocols for model development, calibration, and validation. The content is structured to serve as a practical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to translate quantitative models into biological insights and therapeutic advances.

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models

Framework Fundamentals

ODE models form the cornerstone of dynamic modeling in systems biology, representing the rates of change of system components as functions of their current state. For inflammatory processes, this typically involves modeling concentrations of cytokines, immune cell populations, and physiological indicators over time [6] [23]. A system of ODEs can capture the core dynamics of inflammation, including production, interaction, and degradation of key mediators.

A typical ODE model for inflammatory dynamics takes the form:

[ \frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{x}, t, \mathbf{\theta}) ]

Where (\mathbf{x}) is the vector of state variables (e.g., concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10), (t) is time, and (\mathbf{\theta}) represents model parameters (e.g., production rates, degradation constants).

Application in Inflammation Research

ODE models have been successfully applied to simulate the inflammatory response to various stimuli. A recent mechanistic ODE model of the human inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure exemplifies this approach [6]. This model comprises 15 equations and 48 parameters, simulating processes at both cellular and organism levels:

- Cellular level: Immune cell activation and cytokine release

- Organism level: Changes in body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure

The model incorporates key inflammatory mediators including pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-6, IL-1β) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, which provides negative feedback to regulate the inflammatory response [6]. This negative feedback is crucial for preventing uncontrolled inflammation and is implemented in the model as an inhibitory effect of IL-10 on pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression.

Protocol: Developing an ODE Model for Inflammatory Dynamics

Objective: Create a mechanistic ODE model to simulate inflammatory cytokine dynamics in response to LPS challenge.

Materials and Software:

- ODE-Designer (open-source software for building and simulating ODE models) [24]

- Programming environments: MATLAB, Python with SciPy, or Julia with SciML

- Experimental data for calibration (e.g., cytokine measurements from endotoxemia studies)

Procedure:

Model Formulation

- Define state variables (e.g., resting immune cells, activated immune cells, cytokine mRNA, cytokines in plasma)

- Establish model structure based on known biology (Figure 1)

- Formulate differential equations for each state variable

- Implement negative feedback loops (e.g., IL-10 inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines)

Parameter Estimation

- Compile literature values for known parameters (e.g., cytokine half-lives)

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Estimate sensitive parameters through model calibration to experimental data

- Apply identifiability analysis (e.g., profile likelihood) to ensure unique parameter estimation

Model Simulation and Validation

- Solve ODE system using appropriate numerical solvers (e.g., Runge-Kutta methods)

- Validate model by comparing simulations to independent experimental data

- Test model performance under different conditions (e.g., acute vs. prolonged LPS exposure)

Figure 1: ODE Model Structure for Inflammatory Response to LPS. The diagram illustrates the key components and interactions in a mechanistic model of inflammation, including the negative feedback loop mediated by IL-10.

Characteristics of ODE Models for Inflammation

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ODE Models in Inflammatory Research

| Characteristic | Description | Example in Inflammation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | System of differential equations without delayed terms | 15-equation model for LPS response [6] |

| Typical State Variables | Concentrations of cytokines, immune cell populations | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, activated monocytes |

| Common Parameters | Production rates, degradation constants, activation coefficients | mRNA half-lives, cytokine scaling parameters [6] |

| Strengths | Interpretability, well-established analysis methods, computational efficiency | Clear biological interpretation of parameters and mechanisms |

| Limitations | Cannot inherently represent delays without additional equations | May require many compartments to represent complex biological processes |

| Validation Approaches | Parameter sensitivity analysis, comparison to experimental data | Profile likelihood analysis, dose-response validation [6] |

Delay Differential Equation (DDE) Models

Framework Fundamentals

DDEs extend ODE frameworks by incorporating time delays that explicitly represent the temporal gaps between biological events. In inflammatory processes, these delays naturally occur in processes such as cellular activation, gene expression, and protein synthesis. The general form of a DDE system is:

[ \frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{x}(t), \mathbf{x}(t-\tau1), \mathbf{x}(t-\tau2), ..., t, \mathbf{\theta}) ]

Where (\taui) represents discrete time delays, and (\mathbf{x}(t-\taui)) denotes the state of the system at some previous time.

Application in Inflammation Research

In inflammatory modeling, DDEs can represent the time required for immune cell maturation, transcription and translation of cytokine genes, and the development of clinical symptoms following molecular events. While the search results provided do not contain specific examples of DDE applications in inflammation, this framework is particularly valuable for capturing oscillatory behaviors often observed in cytokine dynamics and for representing the maturation periods of immune cells recruited during inflammatory responses.

Protocol: Implementing a DDE Model for Cytokine Dynamics

Objective: Develop a DDE model to capture delayed feedback in inflammatory cytokine networks.

Materials and Software:

- DDE solvers: MATLAB dde23, Python JiTCDDE, or Julia DelayDiffEq

- Parameter estimation algorithms supporting delayed systems

Procedure:

Identify Biological Delays

- Review literature for time scales of key inflammatory processes

- Determine transcription and translation delays for cytokine production

- Identify immune cell maturation and recruitment timeframes

Model Formulation with Delays

- Incorporate discrete delays for cellular activation and protein synthesis

- Implement delayed negative feedback for regulatory mechanisms

- Include possible delays in physiological responses to cytokines

Numerical Solution and Analysis

- Select appropriate DDE solver (e.g., Runge-Kutta methods for DDEs)

- Analyze stability of steady states considering delay parameters

- Investigate potential for delay-induced oscillations

Parameter Estimation

- Use likelihood-based methods adapted for delay systems

- Employ profile likelihood for joint estimation of kinetic parameters and delays

- Validate estimated delays against experimental measurements

Hybrid Multi-Scale Models

Framework Fundamentals

Hybrid multi-scale models integrate different modeling approaches and spatial-temporal scales to capture the complexity of biological systems. In the context of inflammation research, these frameworks typically combine:

- Mechanistic components based on established biological knowledge

- Data-driven components to represent poorly understood processes

- Multiple biological scales from molecular interactions to organ-level physiology

The Universal Differential Equation (UDE) approach exemplifies this framework by embedding machine learning components within mechanistic ODE structures [25]. This hybrid architecture leverages both prior knowledge and data-driven pattern recognition.

Application in Inflammation Research

Hybrid models are particularly valuable for inflammatory processes where some mechanisms are well-characterized while others remain uncertain. For example, in sepsis pathophysiology, the core inflammatory cascade might be represented mechanistically while the complex interactions with tissue damage and repair are captured using data-driven components [6] [25].

The SINDybrid framework demonstrates another hybrid approach, automatically identifying uncertain components in mechanistic models and compensating for them with sparse, interpretable expressions learned from data [26]. This method is especially useful when epistemic uncertainty (from incomplete knowledge) affects parts of the model structure.

Protocol: Developing a Hybrid Multi-Scale Model for Systemic Inflammation

Objective: Create a hybrid model combining mechanistic inflammation dynamics with data-driven components for uncertain processes.

Materials and Software:

- UDE implementation frameworks (e.g., Julia SciML) [25]

- SINDy algorithms for sparse model identification [26]

- Multi-scale data integration platforms

Procedure:

Model Structure Design

- Identify well-established mechanisms to represent mechanistically (e.g., core cytokine interactions)

- Pinpoint processes with epistemic uncertainty for data-driven components

- Define interactions between mechanistic and data-driven elements

- Establish cross-scale connections (e.g., molecular to physiological)

Implementation of Hybrid Architecture

- Develop mechanistic ODE core based on established biology

- Integrate neural networks or symbolic regression components for uncertain processes

- Implement physical constraints (e.g., mass conservation, non-negative concentrations)

- Set up parallel or serial architecture between model components

Model Training and Regularization

- Employ multi-start optimization to avoid local minima

- Apply regularization to data-driven components (e.g., L2 weight decay)

- Use early stopping to prevent overfitting

- Balance contributions of mechanistic and data-driven elements

Validation and Interpretation

- Test model performance on validation datasets not used for training

- Analyze sensitivity to both mechanistic and data-driven parameters

- Assess physical plausibility of predictions

- Interpret learned data-driven components for biological insights

Figure 2: Hybrid Multi-Scale Model Architecture. The diagram illustrates the integration of mechanistic knowledge and data-driven components within a unified modeling framework.

Hybrid Model Architectures in Biological Applications

Table 2: Comparison of Hybrid Modeling Approaches in Biological Research

| Approach | Key Features | Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) | Combines mechanistic ODEs with artificial neural networks [25] | Flexible incorporation of prior knowledge; handles unmodeled dynamics | Glycolysis modeling; sepsis inflammation dynamics [25] |

| SINDybrid Framework | Automatically identifies uncertain model components; uses sparse regression for corrections [26] | Produces interpretable, symbolic corrections; data-efficient | Chemical process modeling; biological reaction systems [26] |

| Parallel H-ODEs | Runs mechanistic and data-driven components simultaneously [27] | Enhances prediction while maintaining physical interpretability | Biological phosphorus removal in wastewater treatment [27] |

| Serial H-ODEs | Data-driven components feed outputs to mechanistic model [27] | Calibrates mechanistic parameters using sensor data | Autotrophic denitrification process modeling [27] |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Incorporates physical constraints into neural network loss functions [25] | Ensures physical consistency of predictions | Systems biology applications with known constraints |

Research Reagent Solutions for Inflammation Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Experimental Data Generation in Inflammation Modeling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Inflammation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Toll-like receptor 4 agonist; induces inflammatory response [6] | Experimental endotoxemia models to stimulate cytokine production |

| ELISA Kits | Quantitative measurement of cytokine concentrations [28] | Validation of cytokine dynamics predicted by mathematical models |

| Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay | Multiplex quantification of inflammatory biomarkers [28] | Simultaneous measurement of multiple cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α) |

| Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Gold standard for protein quantification [28] | Measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP) and cytokine levels in serum |

| Noninvasive Sampling Kits | Collection of urine, sweat, saliva, exhaled breath, and stool samples [28] | Development of noninvasive biomarkers for inflammatory monitoring |

| Core Body Temperature Sensors | Continuous physiological monitoring [28] | Correlation of inflammatory markers with systemic physiological responses |

Comparative Analysis and Framework Selection

Guidelines for Model Selection

Choosing the appropriate modeling framework depends on the specific research question, available data, and biological processes of interest. The following guidelines support framework selection:

ODE models are most appropriate when:

- The system is well-mixed without significant spatial heterogeneity

- Time delays are not critical to the dynamics of interest

- The goal is mechanistic interpretation with moderate complexity

- Computational efficiency is a priority

DDE models should be considered when:

- Significant biological delays exist in the processes of interest

- Oscillatory behavior is observed in experimental data

- Processes like cellular maturation or gene expression are central to the dynamics

Hybrid multi-scale models are most beneficial when:

- The system combines well-characterized and poorly understood components

- Processes span multiple biological scales

- High-dimensional data is available to train data-driven components

- The goal includes both prediction and mechanistic insight

Integrated Modeling Workflow

Figure 3: Integrated Workflow for Inflammation Model Development. The diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting and implementing mathematical frameworks for inflammatory dynamics research.