Molecular Mechanisms of Cytokine Storm in Multiple Organ Failure: From Pathogenesis to Targeted Therapies

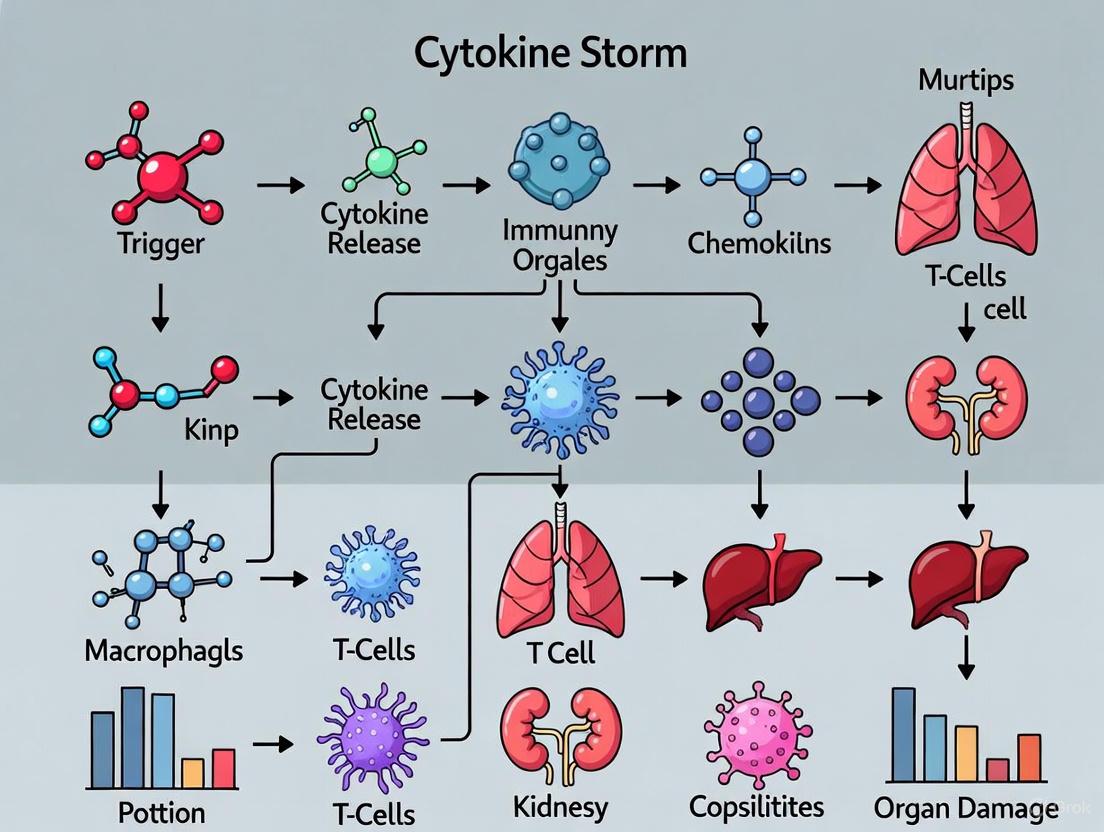

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiology linking cytokine storm (CS) to multiple organ failure (MODS), a life-threatening condition in sepsis, COVID-19, and immunotherapies.

Molecular Mechanisms of Cytokine Storm in Multiple Organ Failure: From Pathogenesis to Targeted Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiology linking cytokine storm (CS) to multiple organ failure (MODS), a life-threatening condition in sepsis, COVID-19, and immunotherapies. We detail the molecular basis of CS, focusing on key signaling pathways like JAK/STAT and Toll-like receptors, and the critical role of inflammatory cell death (PANoptosis). For researchers and drug development professionals, the review explores current and emerging therapeutic strategies, including cytokine antagonists, JAK inhibitors, and extracorporeal therapies. It also covers diagnostic biomarkers, comparative treatment efficacy, and future directions in precision immunomodulation, offering a foundational resource for developing novel interventions.

Unraveling the Molecular Basis of Cytokine Storm and Systemic Inflammation

Cytokine storm (CS) represents a life-threatening systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by excessive immune cell activation and dramatically elevated circulating cytokine levels. This pathophysiological process is implicated in the development of multi-organ failure across diverse clinical conditions, including severe infections, autoimmune disorders, and novel immunotherapies. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of CS-defining clinical syndromes, traces the historical evolution of the concept, delineates underlying molecular mechanisms with a focus on critical signaling pathways, summarizes current experimental models and methodologies, and reviews emerging therapeutic strategies targeting specific components of the dysregulated immune response. The synthesis of current research presented herein aims to facilitate advanced mechanistic research and therapeutic development for this highly lethal condition.

The term "cytokine storm" first appeared in published medical literature in 1993, when James Ferrara used it to describe the engraftment syndrome associated with acute graft-versus-host disease (aGvHD) following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [1] [2]. However, recognition of this hyperinflammatory state predates the terminology, with references to an "influenza-like syndrome" in 1958 describing exaggerated immune responses following systemic viral infections [1]. The conceptual foundation was further established in 1991 when the term "cytokine release syndrome" (CRS) was coined to characterize the inflammatory state and hypercytokinemia following muromonab-CD3 infusion [1].

The cytokine storm concept gained significant traction during the 2005 avian H5N1 influenza pandemic, where it helped explain the severe pathology observed in infected patients [3]. Historical analyses suggest that cytokine storms were likely responsible for the disproportionate number of healthy young adult deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed approximately 50 million people worldwide [2]. Similarly, preliminary research from Taiwan indicated cytokine storm as the probable mechanism for many deaths during the SARS epidemic in 2003 [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the clinical significance of cytokine storms, with many fatal cases attributed to this dysregulated immune response [4] [2].

The evolution of CS as a defined pathological entity has been paralleled by developments in targeted therapeutic approaches. One of the earliest targeted therapies was the anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab, developed in the 1990s for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease [3]. A pivotal moment in CS management came in 2012 when tocilizumab was successfully used to rescue a 6-year-old patient experiencing a severe cytokine storm following CAR T-cell therapy, leading to its subsequent FDA approval for this indication [4].

Defining Clinical Syndromes and Biomarkers

Clinical Syndromes Associated with Cytokine Storm

Cytokine storm represents a severe systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by excessive immune cell activation and significantly increased circulating cytokine levels [1] [5]. This pathological process is implicated in numerous life-threatening conditions, which can be broadly categorized into three main groups:

Table 1: Clinical Syndromes Associated with Cytokine Storm

| Syndrome Category | Specific Conditions | Primary Driving Cells | Key Pathogenic Cytokines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen-Induced | Sepsis (bacterial/viral), COVID-19, Influenza, SARS | Heterogenous immune cells | TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β [6] |

| Autoinflammatory/Monogenic | Primary HLH, Secondary HLH, MAS, CAPS, FMF | CD8+ T cells, Myeloid cells | IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-18 [6] |

| Therapy-Induced | CAR T-cell CRS, ICANS, aGvHD, BiTE therapy | CAR T cells, T cells, Myeloid cells | IL-6, IL-1 [1] [6] |

Cytokine storm syndrome encompasses a diverse set of conditions that can result in this hyperinflammatory state. These include familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), Epstein-Barr virus-associated HLH, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), NLRC4 macrophage activation syndrome, cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and sepsis [2]. While the term "cytokine storm" is often used interchangeably with CRS, it more precisely represents a severe episode of CRS or a component of another disease entity such as macrophage activation syndrome [2].

Clinical Manifestations and Biomarkers

The clinical presentation of cytokine storm includes acute systemic inflammatory symptoms, organ dysfunction, and potentially mortality [1]. Constitutional symptoms often include fever, headache, fatigue, and anorexia. Multi-organ system involvement manifests as confusion and delirium (nervous system); nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (gastrointestinal system); anemia, cytopenia, and coagulopathy (vascular/lymphatic system); hypotension and arrhythmias (cardiac); pneumonitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (pulmonary); hepatomegaly and liver failure (hepatic); and acute kidney injury (renal) [6].

Multiple biomarkers have been identified that correlate with CS severity and prognosis. A meta-analysis of severe COVID-19 cases identified several key biomarkers: lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated levels of interleukin-6, ferritin, D-dimer, aspartate aminotransferase, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, neutrophils, and leucocytes [7]. Elevated IL-6 and hyperferritinemia are particularly notable as red flags for systemic inflammation and poor prognosis [7]. More recent studies have identified CXCL13 as a potential biomarker for predicting patient response to siltuximab in Castleman disease [4].

Table 2: Key Biomarkers in Cytokine Storm Syndromes

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarkers | Association with CS Severity | Potential Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ | IL-6 > 19.5 pg/mL associated with severe disease [8] | Prognostic stratification, treatment guidance |

| Acute Phase Reactants | Ferritin, C-reactive protein, Procalcitonin | Hyperferritinemia, elevated CRP | Disease monitoring, early diagnosis of SIRS |

| Hematological Parameters | Lymphopenia, Thrombocytopenia, Neutrophilia | Degree of cytopenia correlates with severity | Rapid assessment, risk stratification |

| Organ Function Markers | AST, ALT, LDH, Creatinine, D-dimer | Elevation indicates organ damage | Monitoring multi-organ dysfunction |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Key Signaling Pathways in Cytokine Storm

The pathogenesis of cytokine storm involves multiple interconnected signaling pathways that drive excessive cytokine production and inflammatory cell death.

JAK/STAT Pathway

The JAK/STAT pathway represents a highly conserved signaling cascade that plays a significant role in cytokine storm pathogenesis [1]. This pathway consists of three main structural components: transmembrane receptors, receptor-associated JAKs (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2), and STATs (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6) [1]. Multiple cytokines, including ILs, IFNs, and growth factors, participate in JAK/STAT signaling.

IL-6 triggers the JAK/STAT3 pathway through classical cis-signaling, trans-signaling, and trans-presentation mechanisms [1]. IL-6 can interact with both membrane-bound IL-6 receptor (mIL-6R) on immune cells and soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R), forming a complex that activates gp130 and initiates the JAK/STAT3 signaling cascade [1]. This IL-6/IL-6R/JAK/STAT3 activation results in systemic hyperinflammatory response and secretion of various mediators including IL‑1β, IL‑8, CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, GM-CSF, and VEGF [1]. TNF and IFN-γ also activate JAK family kinases, particularly JAK1, leading to phosphorylation and activation of STAT proteins that promote expression of inflammation-related genes [1].

The overactivation of the JAK/STAT pathway has been identified as a key factor in cytokine release and inflammatory disturbances across various diseases, including HLH, aGvHD, CAR-T therapy complications, COVID-19, and fulminant myocarditis [1]. In HLH, elevated levels of various cytokines including IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, TNF, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF primarily activate JAK/STAT pathways, leading to excessive proinflammatory cytokine production [1].

Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) and NF-κB Pathway

Toll-like receptors represent a primitive category of pattern recognition receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns [1]. These receptors are present on various immune cells and tissue cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, serving as detectors of pathogen incursion [1]. TLR activation plays a critical role in the development of infectious diseases and CS progression [1].

Upon recognition of PAMPs, TLRs initiate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and orchestrate immune responses to protect cells from harm [1]. TLR activation leads to production of antiviral cytokines such as type I IFNs, IL-1ß, and IL-6, which directly impede viral replication [1]. However, this release of pro-inflammatory factors may also have deleterious effects, contributing to the cytokine storm phenomenon.

Recent research on jellyfish envenomation syndrome has identified NF-κB p65 subunit activation as central to cytokine storm induction [9]. Transcriptomic analyses in a mouse model of delayed jellyfish envenomation syndrome revealed significant perturbation of the NF-κB signaling pathway following envenomation [9]. Knockdown of p65 in macrophages reduced cytokine production and improved cell viability, demonstrating its crucial role in this process [9].

Inflammatory Cell Death (PANoptosis)

Recent studies have elucidated positive feedback loops between cytokine release and cell death pathways, wherein certain cytokines, PAMPs, and DAMPs can activate inflammatory cell death, leading to further cytokine secretion [6]. This synergistic crosstalk between pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis pathways is referred to as PANoptosis [6].

PANoptosis is regulated by the PANoptosome, a molecular scaffold that enables key molecules from all three cell death pathways to engage contemporaneously [6]. Studies have shown that cytokines are intricately linked to these cell death mechanisms in a positive feedback loop whereby cytokine release causes inflammatory cell death that facilitates further pathogenic cytokine release through membrane pores and cell lysis, culminating in a cytokine storm that drives severe, life-threatening damage to host tissues and organs [6].

Systemic inflammation, tissue damage, multi-organ failure, and mortality in cytokine storm syndromes are prevented by combined treatments with TNF and IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies, which block cytokine-mediated inflammatory cell death in murine models [6]. The identification of cell death-associated molecules, primarily caspase-8, Z-DNA-binding protein 1, transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase, and receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1, as master switches of inflammasome activation and PCD pathways has further established the concept of cytokine-mediated inflammatory cell death [6].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Established Experimental Models for Cytokine Storm Research

Jellyfish Envenomation Syndrome Model

A novel mouse model of delayed jellyfish envenomation syndrome (DJES) has been established to study cytokine storm mechanisms [9]. In this model, mice are injected with tentacle extract from Nemopilema nomurai jellyfish via the tail vein [9]. The venom contains predominantly metalloproteinases and other toxic components such as staphylococcal toxins, coagulation factors, peroxiredoxins, and phospholipases [9].

Experimental Protocol:

- Animals: Laboratory mice (specific strain should be selected based on research objectives)

- Venom Preparation: Tentacle extract obtained from live Nemopilema nomurai jellyfish, purified and standardized

- Administration: Intravenous injection via tail vein at concentrations ranging from 0.7 to 2.29 mg kg−1

- Monitoring: Observation period of 12-48 hours with detailed recording of symptom progression and time to death

- Endpoint Analysis: Histopathological examination of heart, liver, and kidneys; biochemical analysis of organ function markers; cytokine profiling

This model replicates human DJES characterized by acute multi-organ failure and significant upregulation of over 20 pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL2, and CCL4) in the heart, liver, and kidneys [9]. The LD50 decreases from 1.9 to 0.7 mg kg−1 when observation time extends from 12 to 48 hours [9].

In Vitro Macrophage Model

To understand how jellyfish envenomation induces inflammatory cytokine storm, RAW 274.6 macrophages are treated with tentacle extract and examined in vitro [9].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Line: RAW 274.6 macrophages

- Treatment: Tentacle extract at varying concentrations

- Cytotoxicity Assessment: CCK8 assay to determine IC50 (reported as 17.39 µg mL−1 after 6 hours)

- Binding Studies: Immunofluorescence to confirm TE binding to macrophage membrane

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing to identify differentially expressed genes and pathway enrichment

Transcriptomic analysis of TE-treated macrophages identified 51 differentially expressed genes that overlapped with those found in the heart, liver, and kidneys of TE-treated DJES mice [9]. Similar to the in vivo model, the top enriched pathways in treated macrophages were related to inflammation, with NF-κB signaling emerging as a central pathway [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cytokine Storm Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Models | RAW 274.6 macrophages, Primary macrophages, Dendritic cells | In vitro cytokine production studies | Response to PAMPs/DAMPs, cytokine secretion profiling [9] |

| Cytokine Detection | ELISA kits (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ), Multiplex immunoassays, LEGENDplex | Cytokine quantification in serum/tissue | Biomarker identification, pathway activation monitoring [7] [9] |

| Pathway Inhibitors | JAK inhibitors (Ruxolitinib), NF-κB inhibitors, Dexamethasone | Mechanistic studies, therapeutic screening | Target validation, pathway interrogation [1] [9] |

| Transcriptomic Tools | RNA sequencing kits, Microarrays, PCR arrays | Gene expression profiling | Pathway identification, biomarker discovery [9] |

| Histological Reagents | H&E staining kits, Immunofluorescence antibodies | Tissue pathology assessment | Organ damage evaluation, cellular infiltration analysis [9] |

Therapeutic Strategies and Research Directions

Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Current management of cytokine storm typically necessitates a multidisciplinary team strategy encompassing removal of abnormal inflammatory or immune system activation, preservation of vital organ function, treatment of the underlying disease, and provision of life supportive therapy [1]. Several targeted approaches have emerged:

Cytokine-Targeted Therapies:

- IL-6 Inhibition: Tocilizumab (anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody) was one of the earliest targeted therapies developed for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease and has since been approved for CRS associated with CAR T-cell therapy [3] [4].

- IL-1 Inhibition: Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) has demonstrated efficacy in autoinflammatory CS conditions [1].

- IFN-γ Inhibition: Emerging therapies targeting IFN-γ show promise for HLH and other CS conditions [1].

- TNF Inhibition: Anti-TNF agents have been explored for acute graft-versus-host disease and other CS conditions [1].

Intracellular Signaling Inhibitors:

- JAK/STAT Pathway: JAK inhibitors including ruxolitinib have shown promising efficacy in COVID-19, CAR-T associated CRS, and other CS conditions [1]. Inhibition of JAK1 has been shown to reduce CRS associated with CAR-T therapy [1].

- NF-κB Pathway: Dexamethasone, a broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory agent that inhibits NF-κB, effectively suppresses cytokine storm, mitigates multi-organ failure, and improves survival in mouse models of jellyfish envenomation syndrome [9].

Novel Immunomodulatory Approaches:

- Sphingosine Analogues: Targeting sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors have shown potential for controlling virus-induced cytokine storm by downregulating production of IFN-α, CCL2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ [3].

- PPAR Agonists: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors agonists such as gemfibrozil, pioglitazone, and rosiglitazone downregulate inflammatory response to virus-induced lung inflammation [3].

Future Research Directions

Despite therapeutic advances, the overall mortality rate of cytokine storm resulting from underlying diseases remains high [1]. Several key research directions warrant further investigation:

Biomarker Discovery and Validation: Implementation of biomarker tests to inform personalized treatment approaches is crucial [4]. Proteins such as CXCL13 show promise for predicting patient response to specific therapies like siltuximab [4]. Research should focus on validating these biomarkers across different CS syndromes and developing rapid clinical assays.

Personalized Immunomodulation: A personalized approach to treatment based on biomarkers and comorbidities offers significant potential for improving outcomes [8]. This requires better understanding of individual host responses and proper administration timing of immunomodulatory therapies [3].

Combination Therapies: Given the complexity and redundancy of cytokine networks, combination therapies targeting multiple pathways simultaneously may be necessary. Research should explore optimal combinations that maximize efficacy while minimizing immunosuppressive complications.

Novel Molecular Targets: Continued investigation into the molecular mechanisms of CS, including the role of neutrophil extracellular traps, NLRP3 inflammasome, and other signaling pathways may reveal new therapeutic targets [1]. Better understanding of PANoptosis and its regulation may provide opportunities for novel interventions [6].

Cytokine storm represents a complex, life-threatening systemic inflammatory syndrome with diverse clinical manifestations and etiologies. Understanding its historical context, defining clinical syndromes, elucidating molecular mechanisms through appropriate experimental models, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies are crucial for improving patient outcomes. Continued research into the intricate networks of immune activation, inflammatory cell death, and biomarker discovery will enable more precise diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for this highly lethal condition. As research progresses, personalized immunomodulation strategies based on individual patient biomarkers and underlying pathophysiology offer the greatest potential for advancing the management of cytokine storm syndromes.

Cytokine storm (CS) is a life-threatening systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by hyperactivation of immune cells and elevated levels of circulating cytokines, driving the pathogenesis of multiple organ failure [1]. This maladaptive immune response represents a critical juncture in the progression of severe infections, autoimmune disorders, and certain treatment modalities, with high mortality rates stemming from associated complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and fulminant myocarditis [1] [10]. Understanding the precise initiating stimuli and their downstream consequences is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of three principal CS categories—pathogen-induced, autoinflammatory, and therapy-associated—framed within contemporary research on cytokine storm and multi-organ failure mechanisms. We synthesize current knowledge on underlying molecular pathways, diagnostic biomarkers, and experimental approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with essential tools for advancing therapeutic innovation in this critical field.

Pathogen-Induced Cytokine Storm

Mechanisms and Key Pathways

Pathogen-induced cytokine storm represents a dysregulated host response to infectious agents, characterized by excessive activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and subsequent hyperinflammation [11] [10]. The innate immune system detects pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) through various receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) [11]. This recognition triggers downstream signaling cascades, notably NF-κB and AP-1, which upregulate pro-inflammatory gene programs, leading to massive cytokine production [10].

SARS-CoV-2 infection provides a well-characterized model of pathogen-induced CS. The viral spike glycoprotein engages host receptors including ACE2, initiating intracellular signaling that activates multiple PRR pathways [11]. Importantly, SARS-CoV-2 proteins induce mitochondrial damage, resulting in mitochondrial DNA (mitDNA) release that activates the cGAS-STING pathway, contributing to IFN-β expression and vascular damage in severe COVID-19 [11]. Viral evasion strategies, particularly inhibition of IFN-I/III production, further contribute to immune dysregulation [11].

In sepsis, the cytokine storm is driven by uncontrolled systemic inflammation in response to bacterial or other pathogens [10]. PAMPs and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) activate PRRs on innate immune cells, triggering inflammasome formation and activating caspase-1, which processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms [10]. Inflammatory cell death pathways—pyroptosis, necroptosis, and their integration as panoptosis—create a self-amplifying circuit wherein PAMPs, DAMPs, and pro-inflammatory cytokines perpetuate immune dysfunction and tissue injury [10].

Signalling Pathways in Pathogen-Induced Cytokine Storm

The following diagram illustrates key signalling pathways in pathogen-induced cytokine storm, integrating PRR activation, downstream signalling cascades, and cytokine production.

Quantitative Biomarkers and Clinical Parameters

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in Pathogen-Induced Cytokine Storm

| Biomarker | Physiological Role | Association with CS | Cut-off Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; induces acute phase proteins | Primary driver of CRS; correlates with mortality | >19.5 pg/mL predicts severe COVID-19 [8] |

| sCD163 | Scavenger receptor on macrophages; marker of activation | Macrophage activation syndrome; disease severity | Elevated in severe COVID-19 [12] |

| HGF | Tissue repair and anti-inflammatory regulation | Predictor for ICU admission/fatal outcome in COVID-19 | Combined with CXCL13 predicts outcome [12] |

| Pentraxin 3 | Acute phase protein; innate immunity regulation | Predicts COVID-19 disease severity | Elevated in severe cases [12] |

| Serum Amyloid A | Acute phase reactant; modulates innate immunity | Reflects systemic inflammation intensity in sepsis | 1000-fold increase in septic shock [10] |

| Monocyte Distribution Width | Monocyte size heterogeneity | Early sepsis detection in emergency settings | >23.5 optimal cutoff [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathogen-Induced CS

Protocol 1: In Vitro Macrophage Activation Assay

- Objective: To quantify macrophage activation and cytokine production in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

- Materials: Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) or THP-1 cell line; ultrapure LPS (TLR4 agonist); poly(I:C) (TLR3 agonist); cell culture reagents; ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β.

- Procedure:

- Differentiate THP-1 cells into macrophages using 100 nM PMA for 48 hours or isolate MDMs from human blood.

- Seed cells in 24-well plates at 2×10^5 cells/well and allow to adhere overnight.

- Stimulate with LPS (100 ng/mL) or poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL) for 6-24 hours.

- Collect culture supernatants and measure cytokine levels via ELISA.

- Analyze cells for surface activation markers (e.g., CD86, HLA-DR) by flow cytometry.

- Applications: Screening of immunomodulatory compounds; mechanistic studies of PRR signaling [11] [10].

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Biomarker Profiling in Clinical Samples

- Objective: To establish temporal cytokine profiles correlating with disease severity.

- Materials: Serial serum/plasma samples from infected patients; multiplex bead-based array (e.g., Luminex) measuring 50+ analytes; clinical severity scoring system (e.g., SCODA score for COVID-19).

- Procedure:

- Collect blood samples at predetermined intervals (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14 post-admission).

- Process samples within 1 hour of collection; store at -80°C.

- Measure analyte concentrations using validated multiplex panels.

- Correlate analyte levels with daily clinical severity scores using multivariate statistical models.

- Applications: Identification of prognostic biomarkers; patient stratification for targeted therapy [12].

Autoinflammatory Cytokine Storm

Mechanisms and Key Pathways

Autoinflammatory cytokine storm arises from dysregulated innate immunity in the absence of external pathogens, characterized by uncontrolled activation of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) family cytokines and type I interferon (IFN) responses [13]. This category encompasses systemic autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Sjögren's syndrome (SS), where loss of immune self-tolerance leads to aberrant attacks on host tissues [13]. The pathogenesis involves complex interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and breakdown of immune regulatory mechanisms.

The JAK/STAT signaling pathway plays a central role in autoinflammatory CS, transducing signals from multiple cytokine receptors to regulate immune cell differentiation and function [1]. In SLE, enhanced type I IFN signaling creates a positive feedback loop that promotes autoantibody production by B cells and dendritic cell activation [13]. Similarly, in RA, synovial fibroblasts exhibit constitutive activation of STAT3, driving production of pro-inflammatory mediators including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α that perpetuate joint inflammation and destruction [1] [13].

Inflammasome activation represents another critical mechanism in autoinflammatory CS. The NLRP3 inflammasome, activated by various DAMPs, processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, initiating potent inflammatory responses [1]. Gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis further amplifies inflammation by releasing additional DAMPs and cytokines, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of tissue damage and immune activation [10].

Signalling Pathways in Autoinflammatory Cytokine Storm

The following diagram illustrates key signalling pathways in autoinflammatory cytokine storm, focusing on JAK/STAT signalling and inflammasome activation.

Quantitative Biomarkers and Clinical Parameters

Table 2: Key Biomarkers in Autoinflammatory Cytokine Storm

| Biomarker | Associated Conditions | Pathogenic Role | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I Interferons | SLE, Sjögren's syndrome | Initiate autoimmune activation; enhance antigen presentation | Anti-IFN therapies in development [13] |

| IL-6 | Rheumatoid arthritis, adult-onset Still's disease | Promotes Th17 differentiation; acute phase response | Tocilizumab (IL-6R inhibitor) approved for RA [1] [13] |

| TNF-α | Rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis | Drives synovitis; bone and cartilage destruction | TNF inhibitors established therapy [13] |

| IL-1β | Autoinflammatory syndromes (CAPS), Still's disease | Pyrogenic; activates endothelium; neutrophil recruitment | Anakinra (IL-1Ra) effective in autoinflammatory diseases [1] [13] |

| Autoantibodies | SLE (anti-dsDNA), RA (RF, anti-CCP) | Form immune complexes; activate complement | B-cell depletion therapies [13] |

| CXCL13 | SLE, rheumatoid arthritis | B-cell chemoattractant; lymphoid neogenesis | Marker of disease activity [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Autoinflammatory CS

Protocol 1: JAK/STAT Signaling Inhibition Assay

- Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors in suppressing cytokine signaling in autoimmune models.

- Materials: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients or healthy donors; JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib, tofacitinib); recombinant human cytokines (IFN-α, IL-6); phospho-flow cytometry antibodies.

- Procedure:

- Isolate PBMCs using density gradient centrifugation.

- Pre-treat cells with JAK inhibitors (0.1-1000 nM) for 1 hour.

- Stimulate with IFN-α (1000 U/mL) or IL-6 (50 ng/mL) for 15-30 minutes.

- Fix cells with 4% PFA, permeabilize with ice-cold methanol, and stain with anti-pSTAT1 or anti-pSTAT3 antibodies.

- Analyze STAT phosphorylation by flow cytometry.

- Applications: Screening JAK inhibitor potency; personalized medicine approaches for autoimmune diseases [1] [13].

Protocol 2: Inflammasome Activation and Inhibition Assay

- Objective: To measure NLRP3 inflammasome activation and test inhibitory compounds.

- Materials: Human or murine macrophages; NLRP3 activators (ATP, nigericin, uric acid crystals); caspase-1 inhibitor (VX-765); IL-1β ELISA; FLICA caspase-1 assay kit.

- Procedure:

- Prime macrophages with ultrapure LPS (100 ng/mL) for 3 hours.

- Pre-treat with test compounds for 1 hour.

- Activate NLRP3 with ATP (5 mM) or nigericin (10 μM) for 1 hour.

- Measure mature IL-1β in supernatant by ELISA.

- Assess caspase-1 activation using FLICA reagent followed by flow cytometry.

- Applications: Mechanistic studies of autoinflammatory diseases; screening NLRP3 inhibitors [1] [10].

Therapy-Associated Cytokine Storm

Mechanisms and Key Pathways

Therapy-associated cytokine storm represents a significant challenge in modern medical treatments, particularly in immunotherapy. The most characterized form is cytokine release syndrome (CRS) following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, with an incidence ranging from 37% to 93% depending on the construct and malignancy [1]. CRS typically manifests within days of infusion, characterized by excessive activation of CAR-T cells and endogenous immune cells, leading to massive cytokine production including IL-6, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF [1].

The JAK/STAT pathway is critically implicated in therapy-associated CS. Appropriate JAK/STAT activation enhances antitumor activity of CAR-T cells, whereas overactivation contributes to CRS [1]. Inhibition of JAK1 has been shown to reduce CRS severity without completely abrogating CAR-T cell function, suggesting a potential therapeutic approach [1]. Additionally, monocytes and macrophages are now recognized as primary producers of key cytokines like IL-6 and IL-1 during CRS, activated by contact with CAR-T cells or through IFN-γ signaling [1].

Another therapy-associated CS occurs in acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, where donor T cells recognize host antigens, triggering inflammatory cascades [1]. The JAK/STAT pathway mediates pro-GVHD effects of natural killer cells, with STAT1 and STAT3 playing essential roles in cytokine production and regulatory T cell fate determination [1].

Signalling Pathways in Therapy-Associated Cytokine Storm

The following diagram illustrates key signalling pathways in therapy-associated cytokine storm, focusing on CAR-T cell and therapeutic antibody responses.

Quantitative Biomarkers and Clinical Parameters

Table 3: Key Biomarkers in Therapy-Associated Cytokine Storm

| Biomarker | Therapeutic Context | Kinetics | Intervention Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | CAR-T therapy, aGVHD, IT | Peaks within 1-2 days post-infusion | Tocilizumab administration at grade ≥2 CRS [1] |

| IFN-γ | CAR-T therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors | Early rise (within 24 hours) | Predictive marker for severe CRS [1] |

| GM-CSF | CAR-T therapy | Early elevation | Target for prevention (e.g., lenzilumab) [1] |

| sCD163 | CAR-T therapy, aGVHD | Marker of macrophage activation | Correlates with severe neurotoxicity [1] |

| IL-2 | aGVHD, T-cell engaging therapies | Early elevation | Target for inhibition (daclizumab) [1] |

| Angiopoietin-2 | CAR-T therapy | Endothelial activation | Associated with severe CRS and vascular leakage [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Therapy-Associated CS

Protocol 1: In Vitro CRS Model with CAR-T Cells

- Objective: To recapitulate CRS in vitro and test prophylactic or therapeutic interventions.

- Materials: CAR-T cells (CD19-targeting or other specificity); target tumor cell lines; human PBMCs or monocyte-derived macrophages; cytokine measurement platform.

- Procedure:

- Co-culture CAR-T cells with target tumor cells at various effector:target ratios (e.g., 1:1 to 10:1).

- Add PBMCs or macrophages to the system (CAR-T:tumor:PBMC ratio of 1:1:2).

- Collect supernatants at 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours for cytokine analysis (IL-6, IFN-γ, GM-CSF).

- Test JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib) or monoclonal antibodies (tocilizumab) added at time of co-culture or after cytokine elevation.

- Applications: Preclinical assessment of CRS risk for novel CAR constructs; screening mitigation strategies [1].

Protocol 2: JAK Inhibitor Efficacy in Humanized Mouse Models

- Objective: To evaluate JAK inhibition for managing therapy-associated CS in vivo.

- Materials: NSG mice; human PBMCs (for GVHD model) or CAR-T cells plus tumor cells (for CRS model); ruxolitinib; monitoring equipment.

- Procedure:

- For GVHD: Inject human PBMCs intravenously to create xenogeneic GVHD model.

- For CRS: Establish tumor xenografts followed by CAR-T cell infusion.

- Administer ruxolitinib (30-60 mg/kg twice daily) prophylactically or therapeutically.

- Monitor mice for clinical scores, weight loss, and survival.

- Measure human cytokine levels in serial blood samples using species-specific ELISA.

- Applications: In vivo validation of JAK inhibitors for CS management; dose optimization studies [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cytokine Storm Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| JAK/STAT Inhibitors | Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2), Tofacitinib (JAK1/3) | Pathogen-induced, autoinflammatory, and therapy-associated CS | Suppresses cytokine signaling; reduces inflammatory gene expression [1] [15] |

| Cytokine Monoclonal Antibodies | Tocilizumab (anti-IL-6R), Anakinra (IL-1Ra) | All CS categories | Neutralizes specific cytokines or blocks their receptors [1] [14] |

| Multiplex Cytokine Arrays | Luminex xMAP Technology, MSD U-PLEX | Biomarker discovery and profiling | Simultaneous quantification of multiple cytokines in limited sample volumes [12] |

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry | Anti-pSTAT1, pSTAT3, pSTAT5 antibodies | Signaling pathway analysis | Measures activation status of intracellular signaling pathways in immune cell subsets [1] |

| Inflammasome Activators | ATP, Nigericin, Monosodium Urate Crystals | Autoinflammatory CS models | Activates NLRP3 inflammasome for mechanistic studies and inhibitor screening [10] |

| Humanized Mouse Models | NSG mice with human immune system | Therapy-associated CS (CAR-T, GVHD) | In vivo modeling of human-specific immune responses and therapeutic efficacy [1] |

Concluding Perspectives

This technical guide has systematically delineated the key initiating stimuli, molecular mechanisms, and research methodologies for investigating cytokine storm across three principal categories. The intricate interplay between pathogen recognition, autoimmune dysregulation, and therapeutic interventions reveals both unique and shared pathways that culminate in uncontrolled systemic inflammation. Critical examination of the JAK/STAT pathway, inflammasome activation, and inflammatory cell death mechanisms across these contexts provides a framework for understanding the fundamental principles governing CS pathogenesis.

The evolving landscape of CS research underscores the importance of precision medicine approaches, leveraging biomarker profiles for early intervention and patient stratification. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the temporal dynamics of cytokine networks, identifying novel checkpoint regulators of immune homeostasis, and developing targeted therapies that mitigate pathological inflammation while preserving protective immunity. Integration of advanced technologies including single-cell multi-omics, computational modeling, and humanized systems immunology will accelerate progress in this critically important field, ultimately reducing the burden of multi-organ failure and mortality associated with cytokine storm syndromes.

Cytokine storm (CS), also referred to as cytokine release syndrome (CRS), is a life-threatening systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by hyperactivation of immune cells and elevated levels of circulating cytokines. This pathological process is implicated in the development of severe conditions including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure (MOF), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), and complications from immunotherapies [1]. The uncontrolled and aberrant inflammatory response, rather than the pathogen itself, can result in unintended complications and multi-organ failure [16]. At the core of this dysregulated immune response are key inflammatory mediators, notably Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), Interleukin-1 (IL-1), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines form a complex signaling network that amplifies inflammation, leading to collateral vital organ damage [16] [1]. This review provides an in-depth examination of these four core mediators, their interconnected signaling pathways, and their collective contribution to the pathogenesis of cytokine storm and subsequent multiple organ dysfunction.

Cytokine Profiles and Pathophysiological Roles

The table below summarizes the core structural and functional characteristics of each key inflammatory mediator.

Table 1: Characteristics and Pathogenic Roles of Core Inflammatory Mediators

| Cytokine | Primary Cell Sources | Main Receptors | Key Signaling Pathways | Major Pathogenic Roles in Cytokine Storm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Macrophages, Monocytes, Lymphocytes | TNFR1, TNFR2 | NF-κB, MAPK | Endothelial damage, vascular permeability, coagulopathy, fever, apoptosis [16] [17] |

| IFN-γ | NK cells, NKT cells, Th1 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells | IFNGR1, IFNGR2 | JAK-STAT | Macrophage activation, MHC upregulation, promotes Th1 polarization, tissue immunopathology [18] [19] |

| IL-1 (IL-1α/IL-1β) | Macrophages, Monocytes (IL-1β);Non-immune cells (IL-1α) | IL-1R1, IL-1RAcP | MyD88/NF-κB, MAPK | Fever, acute phase response, pyroptosis, "alarmin" function (IL-1α), potent pro-inflammatory effects [20] [21] |

| IL-6 | Macrophages, Dendritic cells, Epithelial cells | IL-6R, gp130 | JAK-STAT | Acute phase response, B/T cell differentiation, fever, inflammation amplifier [1] [22] |

Quantitative Cytokine Levels in Clinical Scenarios

The concentration of these cytokines in circulation can provide critical insights into disease severity and prognosis during a cytokine storm.

Table 2: Cytokine Levels in Human Cytokine Storm Conditions

| Cytokine | Baseline Level (Healthy) | Level in Inflammatory Disease | Association with Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | Low or undetectable | - Septic Hyperinflammation: >3 pg/mL defines IFNγ-driven sepsis (IDS) endotype [19].- HLH: Markedly elevated [1]. | High levels with concurrent CXCL9 >2200 pg/mL linked to increased mortality in sepsis [19]. |

| IL-6 | Low (pg/mL range) | - COVID-19 ARDS: Significantly elevated vs. non-ARDS patients [23].- IAV Infection: Correlates with disease severity and poor outcomes [22]. | A predictor of mortality in severe COVID-19; levels increase in non-survivors [23]. |

| TNF-α | Low (pg/mL range) | - COVID-19 ARDS: Elevated in ARDS patients vs. controls [23].- MOF: Transmembrane TNF-α (tmTNF-α) on neutrophils is a potential diagnostic marker for CS [17]. | tmTNF-α expression correlates with liver/kidney damage in MOF mice; better CS diagnostic value than serum TNF-α [17]. |

| IL-1β | Low (pg/mL range) | Elevated in severe inflammatory and autoinflammatory diseases (e.g., CAPS, Still's disease) [20]. | Caspase-1 activity and plasma IL-18 (IL-1 family) correlate with COVID-19 severity [16]. |

Signaling Pathways in Cytokine Storm

The pathogenesis of cytokine storm involves the dysregulation of several key intracellular signaling pathways, which are activated by the core mediators upon binding to their respective receptors.

The JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK-STAT pathway is a highly conserved signaling cascade critical for the cellular responses to numerous cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-6 [1]. The pathway consists of transmembrane receptors, receptor-associated Janus kinases (JAKs), and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) [1].

- IFN-γ Signaling: Binding of IFN-γ to its receptor (IFNGR1/IFNGR2) activates receptor-associated JAK1 and JAK2, which phosphorylate STAT1. Phosphorylated STAT1 forms homodimers (known as gamma-activated factor, GAF), translocates to the nucleus, and drives the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) with diverse pro-inflammatory functions [18] [1].

- IL-6 Signaling: IL-6 binds to its membrane-bound IL-6 receptor (mIL-6R) or soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R), leading to gp130 dimerization and activation of JAK1/JAK2. This primarily results in the phosphorylation and dimerization of STAT3, which translocates to the nucleus to promote the expression of a wide portfolio of inflammatory genes, including IL-1β, IL-8, CCL2, and GM-CSF [1]. This IL-6/IL-6R/JAK/STAT3 activation cascade results in a systemic hyperinflammatory response [1].

The IL-1/TLR Signaling Pathway

The IL-1/TLR pathway is fundamental to innate immunity [20]. The cytosolic segment of each IL-1 receptor family member contains the Toll-IL-1-receptor (TIR) domain, which is also present in Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [20] [21].

- Receptor Activation: IL-1 (IL-1α or IL-1β) first binds to the ligand-binding chain (IL-1R1), followed by recruitment of the coreceptor chain (IL-1RAcP). Similarly, TLRs are activated by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [16] [1].

- Downstream Signaling: The formation of the receptor complex brings the intracellular TIR domains together, enabling the recruitment of the adaptor protein MyD88. This initiates a signaling cascade involving IRAK kinases and TRAF6, ultimately leading to the activation of the IKK complex [20] [21]. The IKK complex phosphorylates the inhibitory protein IκB, targeting it for degradation and thus releasing the transcription factor NF-κB. NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and drives the expression of a large portfolio of inflammatory genes, including the cytokines themselves (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), chemokines, and adhesion molecules [16] [21]. This pathway is a primary driver of the pro-inflammatory gene expression seen in cytokine storm.

The Inflammasome Pathway

The inflammasome pathway is a critical platform for the maturation of key cytokines of the IL-1 family, primarily IL-1β and IL-18 [16] [21].

- Two-Step Process: Activation is typically a two-step process. A priming signal (e.g., from TLRs) induces the expression of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, as well as inflammasome components themselves. A second activation signal (e.g., ATP, viral RNA, ROS) triggers the assembly of the inflammasome complex (e.g., NLRP3) [16].

- Caspase-1 Activation and Pyroptosis: The inflammasome recruits and activates caspase-1. Active caspase-1 then performs two critical functions: 1) It cleaves the pro-forms of IL-1β and IL-18 into their mature, bioactive forms. 2) It cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), generating N-terminal fragments that oligomerize and form pores in the plasma membrane [16] [21]. These pores allow the release of the mature cytokines and also lead to a pro-inflammatory form of lytic cell death called pyroptosis, which further amplifies the inflammatory response by releasing cellular contents [16]. SARS-CoV-2 proteins have been shown to promote activation of inflammasomes such as the NLRP3 inflammasome [16].

Experimental Methodologies for Cytokine Research

Key Assays and Techniques

Studying cytokine storm requires a multifaceted experimental approach to quantify cytokines, characterize immune cell responses, and assess resulting organ damage.

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols for Cytokine Storm Research

| Methodology | Key Application | Technical Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Quantification of soluble cytokines in serum/plasma. | Uses specific antibodies to capture and detect target cytokines, with colorimetric or chemiluminescent readouts. | Used to measure TNF-α, IL-18, INF-γ, IL-6, IL-4, and CRP in mouse plasma [17] and human serum [23]. |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Analysis of cell surface and intracellular proteins in immune cells. | Uses fluorescently labeled antibodies to detect markers on or in single cells suspended in a fluid stream. | Used to analyze transmembrane TNF-α (tmTNF-α) expression on neutrophils and PBMCs in mouse models of MOF [17]. |

| Histopathology (H&E Staining) | Assessment of tissue damage and immune cell infiltration. | Tissue sections are stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize overall structure and nuclei/cytoplasm. | Used to evaluate liver and kidney tissue damage (sinus congestion, necrosis, inflammatory infiltration) in MOF mice [17]. |

| Animal Models of Cytokine Storm | In vivo study of CS pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. | Models include LPS/D-Galactosamine-induced liver failure/MOF [17] and pathogen-specific infections (e.g., IAV in mice [22]). | The LPS/D-Gal mouse model reproduces key features of human CS, including elevated cytokines and organ dysfunction [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Cytokine Storm Investigation

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines | Used as positive controls, to stimulate cells in vitro, or to create animal models of hyperinflammation. | Recombinant IFNγ is used in studies to restore immune function in immunosuppressed sepsis [19]. |

| Cytokine-Specific Antibodies | Core reagents for detection techniques like ELISA, Flow Cytometry, and Immunohistochemistry. | PE-conjugated anti-mouse TNF-α antibody for flow cytometry [17]; antibody pairs for cytokine-specific ELISA kits [17] [23]. |

| Cytokine Neutralizing Antibodies / Inhibitors | To block cytokine activity in vitro and in vivo, establishing mechanistic causality. | Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) [20] [24]; Bermekimab (anti-IL-1α mAb) [24]; JAK inhibitors (target JAK-STAT pathway) [1]. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | A potent PAMP used to trigger innate immune responses and induce experimental inflammation and endotoxemia. | Used in combination with D-Galactosamine to create a mouse model of acute liver failure and MOF [17]. |

| ELISA Kits | Ready-to-use kits for standardized quantification of specific cytokine concentrations in biological fluids. | Commercial kits used to measure TNF-α, IL-18, INF-γ, IL-6, IL-4, and CRP in mouse plasma [17]. |

| Flow Cytometry Staining Reagents | Antibodies, buffers, and viability dyes for immunophenotyping and intracellular cytokine staining. | Stromatolyser-4DL FFD-201A for lysing RBCs; staining buffers and fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for surface/intracellular markers [17]. |

The core inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1, and IL-6 function as an integrated network, driving the hyperinflammation characteristic of cytokine storm through interconnected signaling pathways like JAK-STAT, IL-1/TLR, and the inflammasome. Their pathogenic role is underscored by clinical data showing elevated levels in severe conditions like COVID-19 ARDS, sepsis, and MOF. Targeting these cytokines and their pathways (e.g., with JAK inhibitors or IL-1 blockers) has demonstrated therapeutic potential, highlighting their centrality in cytokine storm pathology. Future research should focus on further elucidating the temporal dynamics of these mediators and validating novel biomarkers like tmTNF-α to improve diagnostics and personalize immunomodulatory therapy for life-threatening inflammatory syndromes.

Cytokine storms (CS), or cytokine release syndrome, represent a life-threatening hyperinflammatory condition triggered by infections, immunotherapies, and systemic immune dysregulation. Recent research has identified PANoptosis—a unique, inflammatory programmed cell death pathway that integrates components of pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis—as a central driver of this pathological cascade. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms by which PANoptosis initiates and amplifies cytokine storms, creating a vicious cycle of inflammation and cell death that culminates in multi-organ dysfunction. Through analysis of current evidence from viral infections and immunotherapy models, we explore how PANoptosome complexes sense inflammatory cues to coordinate simultaneous activation of multiple cell death pathways. Furthermore, we discuss emerging therapeutic strategies that target PANoptosis to disrupt this lethal loop, offering novel approaches for managing cytokine storms in critically ill patients.

PANoptosis represents a transformative concept in cell death biology, first conceptualized by Kanneganti's team in 2019 as an inflammatory programmed cell death pathway that cannot be fully explained by pyroptosis, apoptosis, or necroptosis alone [25]. This pathway is characterized by the simultaneous activation of key molecules from all three death pathways, organized within sophisticated multiprotein complexes called PANoptosomes [26]. The functional outcome of PANoptosis is lytic cell death driven by caspases and receptor-interacting protein kinases (RIPKs), resulting in the massive release of inflammatory mediators [26].

Cytokine storms represent a state of uncontrolled systemic inflammation characterized by excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-18, TNF-α, and IFN-γ [27]. Clinically, this manifests as fever, hypotension, multi-organ dysfunction, and potentially death. Recent evidence positions PANoptosis as a critical nexus in cytokine storm pathogenesis, creating a self-amplifying loop wherein cell death releases inflammatory molecules that in turn trigger further cell death [27] [28]. This deadly cycle is particularly relevant in the contexts of severe infections (including SARS-CoV-2 and influenza) and immunotherapy-induced toxicity [27].

Understanding the molecular architecture of PANoptosis and its regulatory mechanisms provides unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cytokine storm pathologies. This whitepaper examines the current state of knowledge regarding PANoptosis-driven cytokine storms within the broader context of multiple organ failure mechanisms research.

Molecular Mechanisms of PANoptosis

PANoptosome Complex Architecture

The core executor of PANoptosis is the PANoptosome, a multiprotein complex that serves as a molecular platform for integrating signals from multiple cell death pathways. PANoptosomes typically contain: (1) sensors for pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs); (2) adaptor proteins; and (3) catalytic effectors from pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis pathways [29]. To date, several distinct PANoptosomes have been characterized, each activated by specific triggers and containing unique sensor components.

Table 1: Characterized PANoptosome Complexes and Their Components

| PANoptosome Type | Key Sensor Molecules | Adaptor Proteins | Catalytic Effectors | Primary Activators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBP1-PANoptosome | ZBP1, NLRP3 | ASC, FADD | Caspase-1/3/6/8, RIPK1/3, MLKL | Influenza A virus, viral Z-RNA [25] [26] |

| AIM2-PANoptosome | AIM2, Pyrin, ZBP1 | ASC, FADD | Caspase-1/8, RIPK1/3 | Francisella novicida, HSV-1, cytosolic DNA [25] [26] |

| RIPK1-PANoptosome | RIPK1, NLRP3 | ASC, FADD | Caspase-1/8, RIPK3 | TAK1 inhibition, Yersinia infection [25] [26] |

| NLRP12-PANoptosome | NLRP12, NLRP3 | ASC | Caspase-8, RIPK3 | Heme plus PAMPs, TNF [26] [30] |

The assembly of these complexes is governed by domain-specific homotypic and heterotypic interactions between molecular components, allowing for context-specific activation in response to diverse cellular threats [26]. This modular architecture provides the structural basis for the simultaneous engagement of multiple cell death pathways.

Signaling Pathways and Execution Mechanisms

Upon activation, PANoptosomes coordinate a sophisticated execution program that engages multiple cell death effectors simultaneously:

- Pyroptotic Component: Caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), generating N-terminal fragments that form membrane pores, and processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms [26] [31].

- Apoptotic Component: Caspase-8 activates executioner caspases (caspase-3/7) and cleaves Bid, connecting extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways [26] [30].

- Necroptotic Component: RIPK3 phosphorylates MLKL, leading to membrane disruption and lytic cell death [26].

Recent research has identified NINJ1 (ninjurin 1) as a key executioner protein that operates alongside other pore-forming proteins during PANoptosis-mediated plasma membrane rupture [29]. This comprehensive engagement of death effectors ensures robust elimination of compromised cells while triggering substantial inflammatory signaling.

Figure 1: PANoptosis Signaling Pathway in Cytokine Storm Pathogenesis. This diagram illustrates the sequential activation of PANoptosis components and the self-amplifying loop that drives cytokine storm progression.

PANoptosis in Cytokine Storm Pathogenesis

Establishing the Death-Inflammation Loop

PANoptosis drives cytokine storms through several interconnected mechanisms that create a self-reinforcing inflammatory cascade:

Direct Cytokine Release: PANoptosis activation results in the maturation and release of potent inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-1β and IL-18, through caspase-1-mediated cleavage [25] [31]. These cytokines initiate local and systemic inflammatory responses.

DAMP Amplification: The lytic nature of PANoptosis results in the release of intracellular contents including ATP, HMGB1, and DNA, which function as DAMPs [28]. These molecules engage pattern recognition receptors on neighboring cells, propagating inflammatory signaling and additional rounds of PANoptosis.

Immune Cell Recruitment and Activation: Released cytokines and DAMPs recruit and activate innate immune cells, particularly macrophages and neutrophils, which in turn produce additional inflammatory mediators including TNF-α and IFN-γ [27] [30]. These cytokines can further sensitize cells to PANoptosis, creating a positive feedback loop.

Table 2: Key Molecular Mediators in PANoptosis-Driven Cytokine Storms

| Mediator Category | Specific Molecules | Source | Pathogenic Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Cytokines | IL-1β, IL-18 | Caspase-1 cleavage in PANoptosis | Fever, endothelial activation, leukocyte recruitment [27] [31] |

| Pore-Forming Proteins | GSDMD, GSDME, MLKL, NINJ1 | PANoptosis execution | Membrane permeabilization, lytic cell death, DAMP release [26] [29] |

| Cell Death Kinases | RIPK1, RIPK3 | PANoptosome core | Necroptosis signaling, inflammasome regulation [25] [30] |

| Transcriptional Regulators | IRF1 | Upstream signaling | Regulates expression of ZBP1, AIM2, NLRP12 [26] |

Evidence from Disease Models

Research across multiple disease models has established the central role of PANoptosis in cytokine storm pathogenesis:

Viral Infections: In influenza A virus infection, ZBP1-PANoptosome activation triggers PANoptosis with concurrent activation of caspase-1 (pyroptosis), caspase-3/8 (apoptosis), and RIPK3/MLKL (necroptosis) [25] [26]. Inhibition of all three pathways is required to block cell death, demonstrating the functional integration within PANoptosis.

Sepsis: PANoptosis contributes significantly to multi-organ dysfunction in sepsis by promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines that disrupt immune cell homeostasis and exacerbate organ damage [28]. Studies demonstrate that PANoptosis inhibition improves survival in septic models.

Immunotherapy Toxicity: In chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy and other immunotherapies, PANoptosis has been identified as a key contributor to cytokine release syndrome pathology [27]. The extensive tissue damage and immune activation triggered by these therapies creates ideal conditions for PANoptosis initiation.

The feed-forward nature of the PANoptosis-cytokine storm loop explains the rapid clinical deterioration observed in these conditions and underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway.

Experimental Analysis of PANoptosis

Methodologies for PANoptosis Detection

Comprehensive assessment of PANoptosis requires multiparameter experimental approaches that simultaneously evaluate markers across all three cell death pathways:

Table 3: Essential Methodologies for PANoptosis Detection and Characterization

| Methodology Category | Specific Techniques | Key Readouts | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Death Assessment | Time-lapse microscopy, LDH release, propidium iodide uptake | Membrane integrity, lytic cell death | Requires comparison with single pathway inhibitors [26] |

| Protein Activation Analysis | Western blot, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry | Caspase-1/3/8 cleavage, pMLKL, GSDMD cleavage | Multiple markers must be assessed simultaneously [25] [29] |

| Complex Formation Studies | Co-immunoprecipitation, ASC speck formation, proximity ligation | PANoptosome assembly, protein-protein interactions | Cell-type and stimulus specific variations occur [26] |

| Genetic Manipulation | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout, siRNA knockdown, dominant-negative constructs | ZBP1, AIM2, RIPK1, RIPK3, caspase function | Functional redundancy may require multiple knockouts [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PANoptosis Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANoptosis Inducers | Influenza A virus, Francisella novicida, HSV-1, heme + PAMPs | Experimental PANoptosis triggering | Activate specific PANoptosomes (ZBP1, AIM2, NLRP12) [25] [26] |

| Gene Targeting Tools | ZBP1 KO cells, RIPK1 kinase-dead mutants, caspase-8 deficient cells | Pathway necessity testing | Establish genetic requirements for PANoptosis [25] [30] |

| Chemical Inhibitors | VX-765 (caspase-1), Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1), GSK'872 (RIPK3) | Pathway dissection | Inhibit specific death pathways; all three required to block PANoptosis [26] [30] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-pMLKL, anti-GSDMD, anti-cleaved caspase-1 | Pathway activation assessment | Detect specific activation markers of each cell death pathway [25] [29] |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for PANoptosis Investigation. This diagram outlines the key methodological approaches for inducing, inhibiting, and validating PANoptosis in experimental systems.

Therapeutic Targeting of PANoptosis in Cytokine Storms

Strategic Intervention Points

The molecular characterization of PANoptosis has revealed multiple potential intervention points for disrupting the cell death-inflammation loop in cytokine storms:

PANoptosome Assembly Inhibition: Targeting upstream sensors or adaptor proteins required for PANoptosome formation represents a promising strategic approach. ZBP1, AIM2, and NLRP3 inhibitors could prevent the initiation of the PANoptotic cascade in context-specific manners [25] [31].

Key Effector Molecules: Simultaneous inhibition of multiple cell death effectors may be required to effectively block PANoptosis. Combination therapies targeting caspase-1, caspase-8, and RIPK1/3 have shown promise in preclinical models [30].

Cytokine Neutralization: Existing biologic therapies that target key PANoptosis-associated cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18 antagonists, may provide clinical benefit by interrupting the inflammatory amplification loop [27] [31].

Logic-Gated Approaches: Innovative strategies such as "logic-gated" activation of PANoptosis modulators that target specific cell populations could maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity [25].

Clinical Translation and Challenges

Despite promising preclinical data, several challenges remain in therapeutically targeting PANoptosis:

Contextual Specificity: PANoptosome composition and regulation varies by cell type, trigger, and disease state, necessitating careful patient stratification and context-appropriate therapeutic selection [25] [30].

Redundancy and Compensation: The inherent redundancy in cell death pathways may allow for compensatory activation when individual components are inhibited, potentially limiting efficacy of single-target approaches [26].

Therapeutic Window: Given the essential role of regulated cell death in host defense and homeostasis, achieving selective inhibition of pathological PANoptosis without disrupting physiological cell death represents a significant challenge.

Ongoing clinical trials evaluating inflammasome-targeting therapies may provide valuable insights into the translatability of PANoptosis modulation for cytokine storm management [31].

PANoptosis represents a critical pathogenic mechanism bridging cell death and inflammation in cytokine storm syndromes. The integrated nature of this cell death pathway explains why historical approaches targeting individual death mechanisms have shown limited success in controlling hyperinflammatory states. Future research directions should focus on:

- Structural Resolution of additional PANoptosome complexes to enable rational drug design.

- Dynamic Mapping of PANoptosis regulatory networks across different pathological contexts.

- Advanced Therapeutic Delivery systems capable of cell-type-specific targeting of PANoptosis components.

- Biomarker Development to identify patients with active PANoptosis who would benefit from targeted therapies.

As our understanding of PANoptosis continues to evolve, so too will our ability to strategically intervene in this lethal process. The concept of targeting PANoptosis offers a promising avenue for developing innovative treatments for cytokine storms and improving outcomes in patients undergoing immunotherapy or battling severe infections.

Hyperinflammation, a state of exaggerated and dysregulated immune activation, is a central driver of severe pathological conditions including cytokine storm syndromes, sepsis, and multiple organ failure. This maladaptive response is characterized by the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the massive recruitment of immune cells, leading to collateral tissue damage and organ dysfunction. At the molecular heart of hyperinflammation lie three critically interconnected signaling pathways: the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) system, and the inflammasome activation cascade [32] [33] [34]. Individually, each pathway orchestrates specific aspects of the immune response; together, they form a complex network that amplifies inflammatory signaling, often with devastating clinical consequences. Understanding the mechanisms, regulation, and crosstalk between these pathways is not only fundamental to deciphering the biology of cytokine storms but also paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies to curb immune-mediated organ damage without compromising host defense. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of these core signaling axes, framed within the context of modern cytokine storm research.

The JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway in Hyperinflammation

Pathway Architecture and Mechanism

The JAK-STAT pathway serves as a crucial conduit for transmitting signals from extracellular cytokines and growth factors directly to the nucleus, thereby regulating gene expression programs governing immune cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation [35]. This signaling cascade is notable for its comparative simplicity, comprising three core components: cell surface cytokine receptors, Janus kinases (JAKs), and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs). In humans, four JAK family members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2) and seven STAT proteins (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6) have been identified, each with non-redundant functions and specific cytokine affiliations [32] [35].

The canonical activation mechanism begins with the binding of a cytokine to its cognate receptor, which induces receptor dimerization or oligomerization. This conformational change brings the associated JAK proteins into close proximity, leading to their trans-phosphorylation and activation. The activated JAKs then phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor's cytoplasmic tail, creating docking sites for STAT proteins via their Src homology 2 (SH2) domains. Once recruited, STATs are themselves phosphorylated by JAKs on a conserved tyrosine residue. This phosphorylation triggers STAT dimerization, followed by nuclear translocation where the dimers bind to specific regulatory sequences in target gene promoters, thereby initiating transcription [35]. The pathway is tightly regulated by negative feedback mechanisms, including the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins, protein inhibitors of activated STATs (PIAS), and protein tyrosine phosphatases [35].

Role in Cytokine Storm and Organ Damage

In the context of hyperinflammation, the JAK-STAT pathway transitions from a carefully regulated communication channel to a primary driver of pathological cytokine production. Many of the cytokines central to cytokine storm syndromes, such as interferons (IFNs), interleukins (IL-6, IL-12, IL-23), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), signal predominantly through JAK-STAT cascades [36] [35]. Dysregulation in this pathway can therefore lead to severe immunodeficiencies, autoimmune pathologies, and malignancies.

The role of JAK-STAT signaling extends beyond classical immune cells to include critical functions within the central nervous system (CNS). Despite modest expression levels in the CNS, the pathway is crucial for functions in the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, making it relevant in conditions like Parkinson's disease and other neuroinflammatory disorders [32]. Furthermore, chronic psychological stress and depression are associated with increased pro-inflammatory states within specific brain regions, and JAK-STAT activation influences serotonin receptors and phospholipase C, with implications for stress and mood disorders [32]. In glial cells such as astrocytes and microglia, JAK-STAT activation assumes a pivotal role in regulating the delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, thereby shaping the neuroinflammatory environment within nervous tissues [32].

Table 1: JAK-STAT Family Members and Their Roles in Hyperinflammation

| Component | Primary Association | Role in Hyperinflammation |

|---|---|---|

| JAK1 | IFN-γ, IL-6 family cytokines | Sustained activation linked to autoimmune pathology; key driver of inflammatory signaling. |

| JAK2 | EPO, TPO, GM-CSF | Gain-of-function mutations (e.g., V617F) cause myeloproliferative neoplasms; crucial in hematopoiesis. |

| JAK3 | γc chain cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, etc.) | Mutations cause SCID; targeted for immunosuppression. |

| TYK2 | Type I IFNs, IL-12, IL-23 | Polymorphisms linked to autoimmune diseases (SLE, Crohn's). |

| STAT1 | IFN-α/β, IFN-γ | Promotes anti-viral and pro-inflammatory responses; excessive activation inhibits IL-17. |

| STAT3 | IL-6, IL-10, IL-23 | Central role in Th17 differentiation; key mediator in chronic inflammation and cancer. |

| STAT5 | Prolactin, GM-CSF, IL-2 | Constitutive activation promotes leukemias; regulates immune cell proliferation. |

Experimental Analysis of JAK-STAT Signaling

Investigating the JAK-STAT pathway in the context of hyperinflammation requires a combination of biochemical, cellular, and genomic approaches.

Protocol 1: Assessing STAT Phosphorylation and Nuclear Translocation

- Cell Stimulation: Stimulate immune cells (e.g., primary monocytes, T cells, or macrophage cell lines like THP-1) with a relevant cytokine (e.g., IFN-γ at 10 ng/mL or IL-6 at 50 ng/mL) for time points ranging from 5 minutes to 2 hours.

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells to obtain total protein extracts. For fractionation, use a cytoplasmic extraction reagent followed by a nuclear extraction reagent to separate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions.

- Western Blotting: Resolve proteins via SDS-PAGE, transfer to a membrane, and probe with antibodies against phosphorylated STATs (e.g., p-STAT1 Tyr701, p-STAT3 Tyr705) and total STAT proteins. Antibodies against nuclear markers (e.g., Lamin A/C) and cytoplasmic markers (e.g., GAPDH) validate the fractionation efficiency.

- Immunofluorescence: Seed cells on coverslips, stimulate, fix, and permeabilize. Stain with anti-STAT antibodies and a fluorescent secondary antibody, then visualize via confocal microscopy to directly observe nuclear translocation.

Protocol 2: Gene Expression Profiling of JAK-STAT Targets

- Treatment: Treat cells with a JAK inhibitor (e.g., Ruxolitinib, Tofacitinib) prior to cytokine stimulation.

- RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR: Extract total RNA and reverse transcribe to cDNA. Perform quantitative PCR using primers for known JAK-STAT target genes (e.g., SOCS3, IRF1, CXCL10).

- Data Analysis: Normalize expression to housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) and analyze using the ΔΔCt method to quantify fold changes in gene expression, thereby assessing the functional impact of pathway activation or inhibition.

Diagram 1: JAK-STAT Pathway Activation. This diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade where cytokine binding induces JAK-mediated STAT phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation to drive target gene expression.

Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) as Gatekeepers of Hyperinflammation

TLR Signaling Cascades

Toll-like receptors are a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that constitute the first line of defense in the innate immune system. They are specialized in recognizing conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms, as well as endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from stressed or dying cells [37] [34]. In humans, ten functional TLRs (TLR1-TLR10) are identified, which are strategically localized on either the plasma membrane (TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6) to sense extracellular threats or within endosomal membranes (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9) to detect nucleic acids from internalized pathogens [34].

TLR activation triggers one of two major signaling cascades: the MyD88-dependent pathway, utilized by all TLRs except TLR3, and the TRIF-dependent pathway (also known as the MyD88-independent pathway), which is primarily engaged by TLR3 and TLR4 [34]. The MyD88-dependent pathway is a rapid-response system. Upon ligand binding, TLRs recruit the adaptor protein MyD88, which then recruits interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs). This complex, known as the "myddosome," ultimately leads to the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). IKK phosphorylates IκB, targeting it for degradation and thereby releasing NF-κB, which translocates to the nucleus to induce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [34]. The TRIF-dependent pathway, initiated by TLR3 and TLR4, leads to the delayed activation of NF-κB and also activates interferon regulatory factors (IRF3 and IRF7), which are critical for inducing type I interferons (IFN-α/β) [37] [34].

TLRs in Sepsis and Cytokine Storm

In hyperinflammatory syndromes like sepsis and cytokine storm, the precise regulation of TLR signaling is lost. While essential for initial pathogen clearance, excessive or prolonged TLR activation becomes a primary engine of the "cytokine storm" [34]. This hyper-inflammatory state is characterized by an overwhelming release of inflammatory mediators that exacerbate tissue damage and can lead to complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury (AKI), and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [34]. For instance, in severe COVID-19, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to activate TLR4 and TLR2, correlating with excessive NF-κB activation and cytokine release [37]. Furthermore, genetic polymorphisms in TLRs, such as those in TLR3 and TLR7, can influence disease severity by modulating the host's antiviral and inflammatory response [37].

Table 2: Key Toll-like Receptors in Hyperinflammation

| TLR | Localization | Ligands (PAMPs/DAMPs) | Role in Hyperinflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 (with TLR1/6) | Cell Surface | Bacterial lipopeptides, Viral proteins (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) | Contributes to neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation; exacerbates inflammatory responses. |

| TLR3 | Endosomal | Viral dsRNA | Rare variants associated with severe COVID-19; generally provides host defense. |

| TLR4 | Cell Surface | LPS (Gram-negative bacteria), SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein | Hyperactivation drives cytokine storm, ARDS, and coagulopathy; key therapeutic target. |

| TLR7/8 | Endosomal | Viral ssRNA | X-chromosome location may contribute to sex-based outcome differences in viral infections. |

| TLR9 | Endosomal | Unmethylated CpG DNA | Activation can contribute to systemic inflammation and autoimmunity. |

Experimental Protocols for TLR Research

Dissecting TLR-specific responses is crucial for understanding their contribution to hyperinflammation.

Protocol 1: TLR-Specific Agonist/Antagonist Studies

- Cell Stimulation: Treat human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or macrophages with specific TLR agonists: LPS (TLR4, 100 ng/mL), Pam3CSK4 (TLR2/1, 1 µg/mL), R848 (TLR7/8, 1 µM), or Poly(I:C) (TLR3, 10 µg/mL). To inhibit signaling, pre-treat cells with specific antagonists like TAK-242 (for TLR4) or chloroquine (for endosomal TLRs).

- Cytokine Measurement: After 6-24 hours, collect cell culture supernatants. Analyze cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-α) using multiplex bead-based immunoassays (e.g., Luminex) or ELISA.

- Pathway Analysis: Lyse cells and perform Western blotting to detect key signaling events, such as phosphorylation of IκBα, p65 (NF-κB), and MAPKs (p38, JNK, ERK).

Protocol 2: Gene Silencing in Primary Immune Cells

- siRNA Transfection: Isolate primary human monocytes or dendritic cells. Transfect with siRNA targeting specific TLRs (e.g., TLR4) or adaptor proteins (e.g., MYD88, TRIF) using non-liposomal transfection reagents optimized for primary cells.

- Efficiency Validation: 48-72 hours post-transfection, assess knockdown efficiency by measuring TLR mRNA levels via qRT-PCR or protein levels by flow cytometry.

- Functional Assay: Challenge the silenced cells with relevant TLR ligands and measure downstream outputs like cytokine production and NF-κB reporter activity to confirm the functional consequence of the knockdown.

Diagram 2: TLR Signaling Pathways. This diagram outlines the two principal signaling branches downstream of TLRs: the MyD88-dependent pathway leading to pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and the TRIF-dependent pathway leading to both NF-κB and type I interferon responses.

Inflammasome Activation: The Inflammatory Executioner