Mouse Peritonitis Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Evaluating Inflammatory Responses in Preclinical Research

This article provides a systematic overview of mouse peritonitis models, essential tools for studying inflammatory responses, sepsis, and evaluating novel therapeutics.

Mouse Peritonitis Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Evaluating Inflammatory Responses in Preclinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic overview of mouse peritonitis models, essential tools for studying inflammatory responses, sepsis, and evaluating novel therapeutics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational pathophysiology of peritonitis, details established and novel methodologies like fecal-induced peritonitis (FIP) and cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), and addresses critical troubleshooting for model standardization. It further explores validation techniques, including robust sepsis scoring systems and comparative analyses of model translatability, offering a complete framework for designing, executing, and interpreting preclinical studies in inflammatory diseases.

Understanding Peritonitis Pathophysiology and Model Selection Criteria

The Clinical Significance of Peritonitis in Human Disease

Peritonitis is a serious medical condition characterized by inflammation of the peritoneum, the thin layer of tissue that lines the inner wall of the abdomen and covers the abdominal organs [1] [2]. This condition typically arises from bacterial or fungal infections but can also be triggered by chemical irritation from fluids that leak into the peritoneal cavity from damaged organs [2]. Peritonitis represents a medical emergency that requires immediate intervention, as it can rapidly progress to life-threatening systemic infection (sepsis), organ failure, and death if left untreated [1] [2].

The clinical significance of peritonitis extends across multiple medical specialties, including emergency medicine, surgery, gastroenterology, and nephrology. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the pathophysiology of peritonitis is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies. Mouse models of peritonitis have become indispensable tools for investigating the inflammatory responses, immune mechanisms, and potential treatments for this condition [3] [4] [5].

Classification and Etiology

Peritonitis is clinically classified into different types based on its underlying cause and mechanism. The table below summarizes the main classifications and their characteristics.

Table 1: Classification and Causes of Peritonitis

| Type | Underlying Causes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP) [1] [2] | Liver cirrhosis, kidney disease, ascites from congestive heart failure or cancer [1] [2] | Primary infection without an obvious source of contamination; common in patients with advanced liver disease and ascitic fluid buildup. |

| Secondary Peritonitis [1] [2] | Perforated appendix, stomach ulcer, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, traumatic injury, pancreatitis, surgical complications [1] [2] | Caused by a hole/rupture in an abdominal organ or direct contamination; most common form. |

| Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated [1] | Contamination during dialysis procedures (poor hygiene, tainted equipment) [1] | Infection related to peritoneal dialysis catheters; a major complication of this treatment modality. |

| Chemical Peritonitis [2] | Leakage of sterile fluids (bile, stomach acid, pancreatic enzymes) [2] | Inflammation triggered by non-infectious irritants before potential secondary bacterial infection. |

Pathophysiology and Inflammatory Mechanisms

The pathophysiology of peritonitis involves a complex cascade of immune responses initiated when pathogens or irritants breach the peritoneal cavity. Macrophages play a pivotal role as the first line of defense, recognizing pathogens and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [4]. This cytokine storm recruits neutrophils and other immune cells to the site of infection, leading to the hallmark inflammation of the peritoneum [4].

Recent research has uncovered novel molecular mechanisms driving this excessive inflammation. The transcription factor IKZF1 has been identified as a key regulator that exacerbates the inflammatory response in macrophages during acute peritonitis [3] [4]. Mechanistically, IKZF1 directly represses Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex Iron Sulfur Subunit B (SDHB) by recruiting histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to deacetylate SDHB. This epigenetic silencing disrupts mitochondrial function, leading to reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, reduced ATP production, and succinate buildup, which in turn amplifies pro-inflammatory signaling [3] [4]. This IKZF1/HDAC3-SDHB-succinate axis represents a promising therapeutic target for modulating the inflammatory response in peritonitis.

Figure 1: Inflammatory Signaling Pathway in Peritonitis. The diagram illustrates the key molecular and cellular events triggered by bacterial infection or chemical irritation, culminating in systemic inflammation.

Concurrently, transcriptomic analyses of blood from murine peritonitis models have revealed systemic changes in gene expression. Studies using LPS-induced peritonitis have identified 290 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with 242 upregulated and 48 downregulated [5]. Activated pathways include NOD-like receptor signaling, Toll-like receptor signaling, apoptosis, and phagocytosis, while pathways involved in adaptive immunity, such as Th1/Th2 cell differentiation and T-cell receptor signaling, are suppressed [5]. This systemic immunosuppressive state often follows the initial hyperinflammatory phase and contributes to the vulnerability to secondary infections.

Established Mouse Models of Peritonitis

Mouse models are fundamental for studying the inflammatory responses in peritonitis. The table below summarizes the key quantitative findings from recent studies utilizing different models.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes from Mouse Peritonitis Models

| Model Type | Key Experimental Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) | IKZF1 expression significantly upregulated in macrophages; Lenalidomide treatment attenuated inflammatory responses and lung injury. [3] [4] | Liu et al., 2025 |

| LPS-Induced | 290 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in blood: 242 up-regulated, 48 down-regulated. [5] | Li et al., 2025 |

| MSSA Lethal Peritonitis | 6-times lavage with PD solution significantly reduced 24-h mortality and prevented rough fur, intraabdominal adhesion, and pus formation. [6] | PMC, 2025 |

| IL-1β-Induced | Peritoneal cells harvested 3 hours post intraperitoneal injection of 25 ng IL-1β in 200 µL PBS. [7] | Grieshaber-Bouyer et al. |

Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) Model

The Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) model is a widely used and clinically relevant polymicrobial model that mimics human perforated appendicitis or diverticulitis [3] [4].

Protocol:

- Anesthesia: Induce anesthesia in mice (e.g., 8-week-old male WT) via isoflurane inhalation [4].

- Laparotomy: Perform a midline abdominal incision to exteriorize the cecum.

- Ligation: Ligate the cecum below the ileocecal valve without causing intestinal obstruction.

- Puncture: Puncture the ligated cecum once with a 22-gauge needle to extrude a small amount of feces [4].

- Closure: Return the cecum to the abdominal cavity and close the abdominal wall in layers.

- Resuscitation: Administer subcutaneous saline (e.g., 0.3 mL) for fluid resuscitation immediately after surgery [4].

- Sham Control: For sham-operated controls, perform the same surgical procedure without ligation and puncture.

LPS-Induced Peritonitis Model

The intraperitoneal injection of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall, provides a model for studying the initial systemic inflammatory response [5].

Protocol:

- Animals: Use male C57BL/6 mice (6-8 weeks old) [5].

- Preparation: Prepare an LPS solution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Injection: Administer LPS (e.g., 10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection [5].

- Control Group: Inject control mice with an equal volume of sterile PBS.

- Sample Collection: Euthanize mice at the desired time point (e.g., 3-24 hours post-injection) to collect blood, peritoneal lavage fluid, or tissues for analysis.

IL-1β-Induced Peritonitis Model

This model involves direct injection of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β to study specific aspects of the cytokine-driven inflammatory response [7].

Protocol:

- Injection: Inject mice (e.g., male WT, 8 weeks old) intraperitoneally with 25 ng of IL-1β in 200 µL of PBS [7].

- Harvesting: Euthanize the mice 3 hours post-injection.

- Cell Collection: Harvest peritoneal cells from the peritoneum by lavage with 5 mL of cold PBS [7].

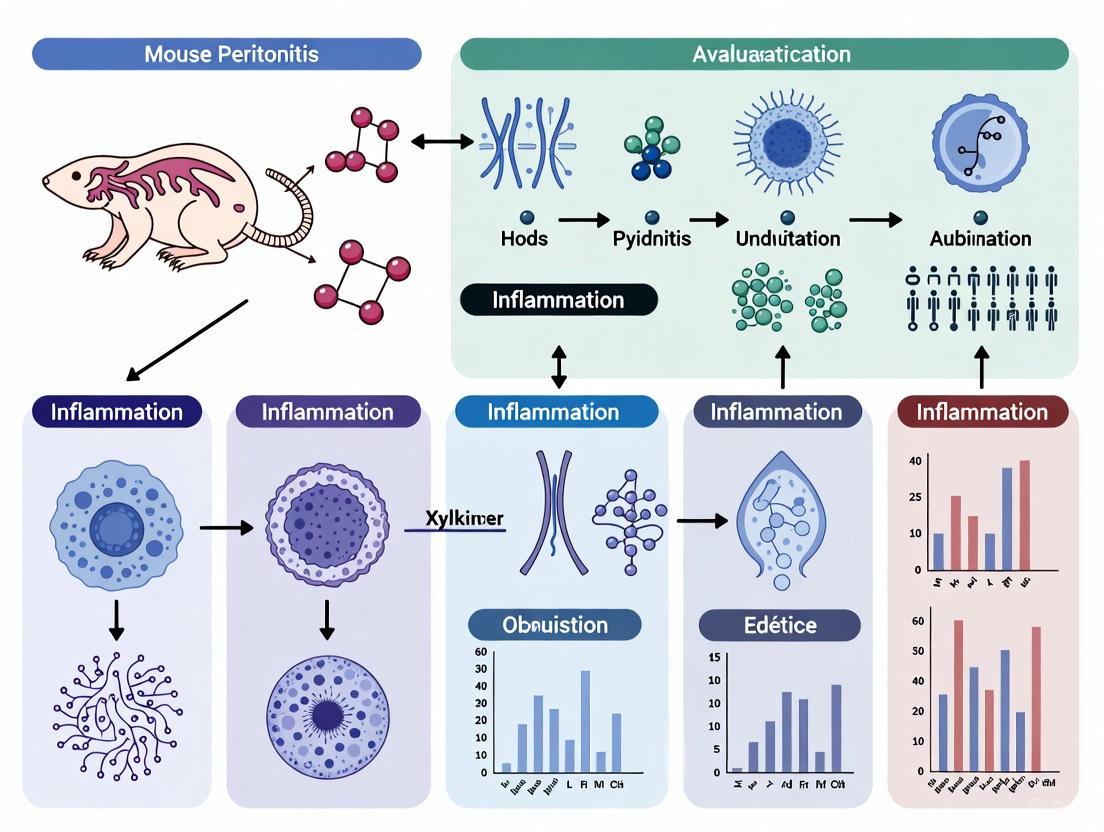

Figure 2: Mouse Peritonitis Model Workflow. The diagram outlines the primary experimental models used in peritonitis research and their main applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in peritonitis research, facilitating experimental reproducibility for scientists and drug developers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Peritonitis Models

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lenalidomide [3] [4] | IKZF1 inhibitor used to attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation and mitigate lung injury. | Administered to assess effects on inflammatory response. |

| Thioglycollate Broth [4] | Elicitant for recruiting macrophages to the peritoneal cavity prior to isolation. | 3% (w/v), injected intraperitoneally 3 days before cell harvest. |

| Low GDP Neutral pH PD Solution [6] | Biocompatible solution for peritoneal lavage; used to study efficacy of lavage monotherapy. | e.g., Midpeliq 135. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) [5] | Endotoxin used to induce sterile, Gram-negative bacterial-like inflammatory response. | 10 mg/kg, administered intraperitoneally. |

| Recombinant IL-1β [7] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine used to induce specific acute inflammatory response. | 25 ng in 200 µL PBS, injected intraperitoneally. |

| MSSA JCM 2413 [6] | Bacterial strain for creating lethal peritonitis models to test therapeutic interventions. | Methicillin-Susceptible S. aureus, e.g., 1x10^10 CFU for LD100 in rats. |

| Antibodies for ELISA [4] | Quantification of cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) in lavage fluid or serum. | e.g., LEGEND MAX Mouse ELISA Kits. |

Therapeutic Insights and Future Directions

Current treatment for peritonitis in humans primarily involves broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care with IV fluids to prevent shock and correct fluid imbalances [2]. Surgical intervention is often required to address the underlying cause, such as repairing a perforated organ [1] [2]. For patients on peritoneal dialysis, strict hygiene protocols are critical for prevention [1].

Research from animal models is driving the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The identification of the IKZF1/HDAC3-SDHB axis suggests that targeting IKZF1 with drugs like lenalidomide or enhancing acetylation with agents like acetate could represent promising adjunct therapies to control excessive inflammation [3] [4]. Furthermore, studies demonstrating that peritoneal lavage with biocompatible PD solution significantly reduces mortality and severity in a lethal peritonitis model, even without antibiotics, challenge current clinical guidelines and suggest a potential role for mechanical cleansing in severe cases [6].

The translation of findings from mouse models to human applications is strengthened by integrated approaches. Validation of hub genes identified in mouse blood transcriptomics (e.g., LDLR, ZAP70) against single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets from human sepsis patients confirms conserved expression patterns and enhances the clinical relevance of these targets [5]. This multi-scale research strategy, combining animal models, omics technologies, and computational biology, provides a powerful framework for uncovering the complex mechanisms of peritonitis and developing more effective, targeted treatments.

Peritonitis, an inflammatory condition of the peritoneal lining, represents a life-threatening clinical challenge with mortality rates remaining as high as 20-35% despite advances in management protocols [8]. This condition arises from diverse etiologies including gastrointestinal perforation, chemical irritation, bacterial contamination, and catheter-related infections [4] [8]. The peritoneal membrane consists of a single layer of mesothelial cells overlying a vascular, lymph-rich sub-mesothelial matrix, functioning as both a physical barrier and an active immune sentinel [8]. Upon insult, resident macrophages and mesothelial cells initiate a robust inflammatory response, releasing cytokines and chemokines that recruit additional immune cells to the infection site [4] [8].

In experimental settings, mouse models of peritonitis have proven invaluable for dissecting the underlying molecular mechanisms. The most commonly employed models include lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced peritonitis, cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), and more recently, meconium slurry-induced peritonitis [5] [3] [9]. These models replicate key aspects of human disease and have identified three central inflammatory pathways that drive disease progression: cytokine signaling, Toll-like receptor (TLR)/NF-κB activation, and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. Understanding the interplay between these pathways provides crucial insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for this devastating condition.

Key Inflammatory Pathways in Peritonitis

Cytokine Signaling Network

Cytokines serve as crucial molecular messengers that coordinate the immune response during peritonitis. Upon peritoneal injury or infection, resident macrophages and mesothelial cells rapidly release pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) [4] [8]. These cytokines function in an orchestrated cascade to amplify the inflammatory response, inducing fever, pain, vasodilation, and endothelial activation that facilitates immune cell infiltration [10] [11]. IL-1β induces the expression of genes that control fever, pain threshold, vasodilatation, and hypotension, while IL-6 serves as a potent inducer of acute phase proteins including C-reactive protein (CRP) [10] [8]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that IL-6 and IL-8 are massively elevated in the ascites of infants with meconium peritonitis, suggesting their potential utility as therapeutic targets [9].

The cytokine network exhibits both synergistic and regulatory interactions during peritonitis progression. For instance, TNF-α can stimulate the production of other cytokines including IL-1β and IL-6, creating an inflammatory amplification loop [11]. Simultaneously, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 are upregulated to counterbalance this pro-inflammatory response and prevent excessive tissue damage [4]. The dynamic equilibrium between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines ultimately determines disease severity and clinical outcomes, with persistent elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines correlating with progression to sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction [4].

TLR/NF-κB Signaling Pathway

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway represents the primary signaling cascade that initiates the inflammatory response in peritonitis. TLRs are pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect conserved microbial components known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, as well as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from injured host cells [12] [10]. In peritonitis, LPS binding to TLR4 activates downstream signaling adaptors including myeloid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88) and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK), ultimately leading to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB [12] [11].

Once in the nucleus, NF-κB functions as a master transcriptional regulator that upregulates the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, and adhesion molecules [10] [11]. Additionally, the TLR/NF-κB pathway provides the essential "priming signal" (Signal 1) for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inducing the transcription of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β [12] [10] [11]. Transcriptomic analyses of blood from LPS-induced peritonitis models have confirmed significant activation of TLR signaling pathways, along with simultaneous suppression of adaptive immunity pathways such as Th1/Th2 cell differentiation and T-cell receptor signaling [5].

NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that serves as a critical platform for caspase-1 activation and subsequent maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 in response to microbial infection and cellular damage [12] [10]. The NLRP3 protein contains three domains: an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD), a central NACHT domain that mediates oligomerization, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain [12] [13]. In peritonitis, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated through a meticulously regulated two-step process: priming (Signal 1) and activation (Signal 2) [12] [10] [11].

The priming step typically occurs through TLR/NF-κB signaling, which upregulates the transcription of NLRP3, pro-IL-1β, and pro-IL-18 [10] [11]. This step also involves post-translational modifications of NLRP3 that license it for subsequent activation [11] [13]. The activation step is triggered by diverse stimuli including extracellular ATP, particulate matter, bacterial toxins, and ionic fluxes, which induce NLRP3 oligomerization and recruitment of the adapter protein ASC and procaspase-1 [12] [10]. This complex formation leads to caspase-1 activation, which cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature, biologically active forms [12] [13]. Additionally, activated caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), whose N-terminal domain oligomerizes to form plasma membrane pores that facilitate cytokine release and trigger an inflammatory form of cell death termed pyroptosis [12] [10].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of Major Inflammatory Pathways in Peritonitis

| Pathway | Molecular Components | Function in Peritonitis |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokine Signaling | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18 | Pro-inflammatory mediators that recruit immune cells, induce fever, pain, and acute phase response |

| TLR/NF-κB | TLR4, MyD88, IRAK, NF-κB | Pattern recognition and initiation of inflammatory gene transcription; provides "Signal 1" for inflammasome priming |

| NLRP3 Inflammasome | NLRP3, ASC, Caspase-1, NEK7 | Caspase-1 activation, IL-1β/IL-18 maturation, pyroptosis execution |

| Downstream Effectors | GSDMD, IL-1β, IL-18 | Pore formation in plasma membrane, pro-inflammatory cytokine activity, pyroptosis |

Recent research has identified the critical involvement of the NIMA-related kinase 7 (NEK7) in NLRP3 inflammasome assembly [12] [13]. NEK7 binds to NLRP3 following activation signals and facilitates the structural rearrangement that exposes PYD domains, allowing for NACHT domain oligomerization and subsequent ASC recruitment [12]. The assembled ASC filaments form a macromolecular structure termed the "ASC speck," which serves as the platform for caspase-1 activation [13]. This intricate assembly process ensures that the potent inflammatory mediators IL-1β and IL-18 are released only when appropriate signals are present, preventing excessive inflammation while effectively combating infection.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Established Mouse Models of Peritonitis

Several well-characterized mouse models of peritonitis have been developed to study the inflammatory pathways involved in disease pathogenesis. The LPS-induced peritonitis model involves intraperitoneal administration of lipopolysaccharide, typically at a dose of 10 mg/kg, which triggers a robust but transient inflammatory response characterized by neutrophil infiltration and cytokine production [5]. This model is particularly useful for studying the early innate immune response and TLR4 signaling pathways. The cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model more closely replicates human polymicrobial sepsis secondary to peritonitis [3] [4]. In this surgical model, the cecum is ligated below the ileocecal valve and punctured with a needle to allow leakage of fecal material into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in a progressive and polymicrobial infection [4].

More recently, a neonatal mouse model of meconium peritonitis has been developed using intraperitoneal administration of human meconium slurry (MS) [9]. This model closely reflects the pathology of human neonatal meconium peritonitis, a non-infectious chemical peritonitis that occurs following fetal intestinal perforation. The model has demonstrated dose-dependent mortality, with an LD40 established at 200 µL per pup, and is characterized by substantial hematological and hepatorenal abnormalities along with increased inflammatory gene expression [9]. Importantly, this model has revealed that the pathogenic agent in meconium is primarily digestive enzymes rather than bacterial components, as antibiotic treatment was ineffective while enzymatic inactivation improved survival rates [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Mouse Models of Peritonitis

| Model Type | Induction Method | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS-Induced | Intraperitoneal injection of LPS (10 mg/kg) | Rapid inflammation, neutrophil infiltration, cytokine release | Study of early innate immune responses, TLR4 signaling, neutrophil recruitment |

| Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) | Surgical ligation and puncture of cecum | Polymicrobial infection, progressive sepsis, systemic inflammation | Modeling human sepsis, antibiotic efficacy studies, long-term outcomes |

| Meconium Slurry | Intraperitoneal administration of human meconium slurry | Chemical peritonitis, sterile inflammation, digestive enzyme-mediated damage | Neonatal meconium peritonitis pathophysiology, sterile inflammatory processes |

Protocol: LPS-Induced Peritonitis in Mice

Purpose: To establish a reproducible model of acute sterile inflammation for studying innate immune responses and early cytokine production.

Materials:

- Male C57BL/6 mice (6-8 weeks old)

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS from E. coli, serotype O111:B4)

- Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- 1 mL syringes with 25-gauge needles

- Isoflurane anesthesia system

- Microtainer tubes for blood collection

Procedure:

- Prepare LPS solution by dissolving in sterile PBS to a concentration of 1 mg/mL.

- Anesthetize mice using isoflurane (3% induction, 1.5-2% maintenance in oxygen).

- Administer LPS (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection using a 25-gauge needle with a total volume of 100-200 µL.

- Return mice to cages with free access to food and water.

- Monitor mice every 2 hours for the first 8 hours, then every 6 hours for 48 hours for signs of distress (pilorection, hunched posture, decreased mobility).

- At desired time points (typically 6, 12, 24 hours), euthanize mice by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation.

- Collect blood via cardiac puncture for serum cytokine analysis.

- Perform peritoneal lavage with 3 mL of ice-cold PBS containing 3 mM EDTA for cellular infiltration analysis.

- Process lavage fluid by centrifugation (500 × g for 5 min at 4°C) and collect supernatant for cytokine measurement.

- Analyze immune cell populations in lavage fluid by flow cytometry or cytospin preparation.

Notes: This model produces robust neutrophil infiltration within 6 hours, peaking at 12-18 hours, with parallel increases in TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels [5]. The inflammatory response typically resolves within 48-72 hours.

Protocol: Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) Model

Purpose: To establish a clinically relevant model of polymicrobial sepsis secondary to peritonitis for studying systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction.

Materials:

- Male C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old, 20-25 g)

- Ketamine/xylazine anesthetic (100/10 mg/kg)

- Ophthalmic ointment

- Heating pad

- Sterile surgical instruments (forceps, scissors, needle holder)

- 5-0 silk suture

- 22-gauge needle

- Normal saline for fluid resuscitation

Procedure:

- Anesthetize mice with ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection.

- Apply ophthalmic ointment to prevent corneal drying.

- Shave and disinfect the abdominal area with alternating betadine and 70% ethanol scrubs.

- Make a 1-1.5 cm midline abdominal incision.

- Exteriorize the cecum carefully using sterile forceps.

- Ligate the cecum below the ileocecal valve with 5-0 silk suture without causing bowel obstruction.

- Puncture the cecum once through-and-through with a 22-gauge needle.

- Gently extrude a small amount of feces (approximately 1 mm) through the puncture site.

- Return the cecum to the abdominal cavity.

- Close the abdominal wall in two layers with 5-0 suture.

- Administer 1 mL of warm normal saline subcutaneously for fluid resuscitation.

- Place mice on a heating pad until fully recovered from anesthesia.

- Administer buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) every 12 hours for postoperative analgesia.

Notes: The severity of sepsis can be modulated by varying the needle size (larger for more severe) or the percentage of cecum ligated [3] [4]. This model produces a progressive inflammatory response with significant cytokine production, immune cell infiltration, and organ dysfunction that mimics human sepsis.

Signaling Pathway Visualization

NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Pathway: This diagram illustrates the two-signal mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Signal 1 (priming) through TLR/NF-κB signaling upregulates NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β transcription. Signal 2 (activation) via diverse stimuli triggers NLRP3 oligomerization and NEK7 binding, leading to inflammasome assembly, caspase-1 activation, and subsequent IL-1β/IL-18 maturation and pyroptosis [12] [10] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Peritonitis Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Findings Using Reagent |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLRP3 Inhibitors | MCC950, CY-09, Lenalidomide | Specific inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly | Lenalidomide (IKZF1 inhibitor) attenuates inflammatory responses and mitigates lung injury in CLP [3] |

| Cytokine Antibodies | Anti-IL-1β, Anti-TNF-α, Anti-IL-6 | Neutralization of specific cytokines | IL-1 antagonists reverse inflammation in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes [14] |

| TLR4 Signaling Inhibitors | TAK-242, LPS-RS, CLI-095 | Blockade of TLR4 signaling pathway | Inhibition prevents priming signal for NLRP3 inflammasome [11] |

| Caspase-1 Inhibitors | VX-765, Z-YVAD-FMK | Inhibition of caspase-1 activity | Blocks maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 [10] [13] |

| ROS Scavengers | Mito-TEMPO, N-acetylcysteine | Reduction of mitochondrial ROS | Attenuates NLRP3 activation signal [10] [11] |

| Ion Channel Modulators | Glybenclamide, Nigericin | Modulation of K+ efflux | Glybenclamide inhibits NLRP3 activation; Nigericin activates via K+ efflux [10] [13] |

| Transcriptional Profiling | RNA-seq kits, PCR arrays (e.g., Mouse Inflammatory Cytokines & Receptors) | Gene expression analysis | Identified 290 DEGs (242 up-regulated, 48 down-regulated) in LPS-induced peritonitis [5] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The intricate interplay between cytokine networks, TLR/NF-κB signaling, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation creates a complex inflammatory milieu that drives disease progression in peritonitis. Recent research has revealed novel regulatory mechanisms, including the role of IKZF1 in exacerbating macrophage inflammation through epigenetic modulation of mitochondrial function in CLP-induced peritonitis [3] [4]. IKZF1 expression is significantly upregulated in macrophages during peritonitis, where it directly represses SDHB expression by recruiting HDAC3 to deacetylate SDHB, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and amplified inflammation [4]. This finding establishes an IKZF1/HDAC3-SDHB-succinate axis driving macrophage hyperactivation and identifies IKZF1 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target [3].

From a translational perspective, targeting these inflammatory pathways holds significant promise for clinical intervention. The NLRP3 inflammasome, in particular, represents an attractive therapeutic target given its central role in processing and releasing mature IL-1β and IL-18 [12] [13]. Several small molecule inhibitors targeting different stages of NLRP3 inflammasome activation have shown efficacy in preclinical models of inflammatory diseases [13]. These include compounds that inhibit NEK7-NLRP3 interaction, disrupt ASC speck formation, or block caspase-1 activity [12] [13]. Additionally, the discovery that disassembly of the trans-Golgi network serves as a common cellular event triggering NLRP3 activation in response to diverse stimuli provides new opportunities for therapeutic intervention [12].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the cell type-specific roles of NLRP3 in peritonitis pathogenesis. While the NLRP3 inflammasome is well-established in myeloid cells, its expression and functionality in non-immune cells, including mesothelial cells, remains controversial [14]. Unbiased transcriptome data sets often report the absence of NLRP3 inflammasome-related transcripts in non-myeloid cells, despite numerous experimental studies reporting NLRP3 expression and activity in these cells [14]. Resolving this discrepancy will require sophisticated cell type-specific knockout models and single-cell transcriptomic analyses of peritoneal tissues during inflammation. Additionally, further investigation is needed to understand the inflammasome-independent functions of NLRP3, such as its role in regulating TGF-β signaling and fibrosis, which may contribute to long-term complications of peritonitis including adhesion formation [14].

In conclusion, the inflammatory pathways in peritonitis represent a complex but orchestrated response to peritoneal injury and infection. A comprehensive understanding of these pathways, particularly the two-signal mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, provides valuable insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. The integration of biomarker profiling with mechanistic studies promises a new era of precision medicine in secondary peritonitis, enabling risk-adapted interventions and improved patient outcomes.

Peritonitis, the inflammation of the peritoneal membrane, initiates a complex cellular response crucial for host defense and tissue repair. The pathophysiology involves a tightly coordinated interaction between immune cells and stromal components, primarily driven by macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts [15] [16]. In mouse models of peritonitis, understanding the roles and interactions of these cells is fundamental for evaluating inflammatory responses and screening potential therapeutic interventions. Macrophages act as central orchestrators of the immune response, neutrophils are the first responders that infiltrate the site of injury, and fibroblasts are the key effectors of tissue remodeling and fibrosis [15] [16] [17]. The dysregulation of these cellular processes can lead to persistent inflammation and peritoneal fibrosis, a serious complication that can cause ultrafiltration failure and necessitate the discontinuation of peritoneal dialysis (PD) [15]. This application note details the mechanisms, protocols, and analytical tools for studying these cellular players in the context of a mouse peritonitis model.

Detailed Cellular Roles and Mechanisms

Macrophages: Orchestrators of Inflammation and Fibrosis

Macrophages exhibit remarkable plasticity, allowing them to adopt different functional phenotypes—or polarization states—in response to microenvironmental signals. This plasticity is central to their role in peritonitis and its outcomes [15].

Activation and Polarization: Macrophages are broadly categorized into classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) phenotypes.

- M1 Macrophages are induced by Th1 cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). They express Toll-like receptors (TLR) 2 and 4, CD80, CD86, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). They secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23, and produce nitric oxide (NO) to combat pathogens [15]. The LPS/TLR4 signaling pathway is a crucial trigger for M1 polarization, leading to the activation of NF-κB and IRF3 and driving the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [15].

- M2 Macrophages are induced by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and TGF-β. They are identified by markers like the mannose receptor (CD206) and CD163 and are further subdivided into M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d subtypes based on the inducing stimuli and specific functions. M2 macrophages are generally involved in tissue repair, angiogenesis, and immunoregulation through the production of IL-10, TGF-β, and various chemokines [15].

Role in Fibrosis: In prolonged peritoneal dialysis, macrophage infiltration and polarization are key contributors to pathology. They show a strong correlation with the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells and directly drive the fibrotic process [15]. M2 macrophages, particularly, are implicated in the production of pro-fibrotic factors that stimulate fibroblasts and lead to excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition [15] [16].

Neutrophils: First Responders and Their Dynamics

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in human blood and are among the first immune cells to be recruited to the site of inflammation during peritonitis [17] [5].

- Infiltration and Recruitment: Neutrophil infiltration is a hallmark of peritonitis. This can be experimentally induced by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of inflammatory agents like CXCL1 or TNF-α [17]. Upon stimulation, neutrophils are rapidly recruited from the bone marrow into the circulation and then to the peritoneal cavity.

- Circulating Dynamics: Recent advancements using in vivo flow cytometry (IVFC) have allowed for the non-invasive, real-time monitoring of circulating neutrophils (LysM-EGFP+ cells) in mouse models. Studies show a significant increase in circulating neutrophils within 20 minutes of TNF-α challenge, accompanied by their concurrent recruitment to the peritoneum and emigration from the bone marrow [17].

- Adhesion and Migration: The adhesion molecule CD18 is critical for neutrophil recruitment from the vasculature into the inflamed peritoneum. Blockade of CD18 was shown to double the number of circulating neutrophils, indicating its essential role in neutrophil extravasation during peritonitis [17].

Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts: Effectors of Tissue Remodeling

The generation and activity of myofibroblasts are central events in the induction of peritoneal fibrosis [16].

- Origin and Activation: Myofibroblasts in the peritoneum can originate from various sources, including resident fibroblasts and mesothelial cells that undergo EMT. These cells are instructed by a network of signals from both stromal resident cells and recirculating immune cells [16].

- ECM Production: Activated myofibroblasts are the primary cells responsible for the abnormal production and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as collagen. This leads to the progressive thickening and scarring of the submesothelial compact zone, a characteristic feature of peritoneal fibrosis [16].

- Cross-talk with Immune Cells: The persistence of myofibroblasts and the progression of fibrosis are fueled by a cross-talk with macrophages. For instance, M2 macrophages secrete TGF-β, a potent pro-fibrotic cytokine that activates fibroblasts and promotes EMT, creating a feed-forward loop that perpetuates fibrosis [15] [16].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research on cellular mechanisms in mouse peritonitis models.

Table 1: Transcriptomic Profile in LPS-Induced Peritonitis Mouse Model

| Parameter | Measurement | Details/Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | 290 Total | 242 upregulated, 48 downregulated [5] |

| Activated Pathways | NOD-like receptor, Toll-like receptor, Apoptosis, Phagocytosis | Bioinformatics analysis of RNA-seq data [5] |

| Inhibited Pathways | Th1/Th2 cell differentiation, T cell receptor signaling | Bioinformatics analysis of RNA-seq data [5] |

| Identified Hub Proteins | 8 Proteins | LDLR, FNBP1L, SNX18, FAM20C, INPP5F, PACSIN1, ZAP70, SYNJ2; structural stability confirmed via 300 ns molecular dynamics [5] |

Table 2: Neutrophil Dynamics in TNF-α-Induced Mouse Peritonitis Model

| Parameter | Measurement | Details/Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Neutrophil Increase | Significant increase | Peaked at ~20 min post i.p. TNF-α injection, monitored by In Vivo Flow Cytometry (IVFC) [17] |

| CD64 Expression on Neutrophils | Significant increase | Measured via flow cytometry and in vivo IVFC with fluorescent antibodies [17] |

| Effect of CD18 Blockade | Doubled circulating neutrophil count | Suggests critical role for CD18 in neutrophil recruitment from vasculature [17] |

Table 3: Macrophage Polarization States and Functions

| Phenotype | Inducing Stimuli | Key Markers | Primary Functions & Secreted Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | IFN-γ, TNF-α, LPS | TLR2/4, CD80/86, iNOS, MHCII | Pro-inflammatory; host defense; secretes TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, NO [15] |

| M2a | IL-4, IL-13 | CD206, CD163, Arg1 | Tissue repair; secretion of CCL17, CCL18, CCL24 [15] |

| M2b | Immune complexes, TLR agonists | CD86, MHC-II | Immunoregulation; secretes IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α [15] |

| M2c | IL-10, TGF-β, glucocorticoids | CD206, CD163, MERTK | Anti-inflammatory, tissue remodeling; secretes IL-10, TGF-β [15] |

| M2d | IL-6, M-CSF, TLR agonists | CD80, CD86, MHC-II | Angiogenesis, immunosuppression; secretes IL-10, TGF-β, CXCL10 [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Circulating Myeloid Cell Dynamics via IVFC

This protocol details the use of in vivo flow cytometry (IVFC) to monitor LysM-EGFP-labeled circulating myeloid cells (primarily neutrophils) in a TNF-α-induced mouse peritonitis model [17].

- Mouse Model: LysM-EGFP transgenic mice (12-16 weeks old, both sexes).

- Key Reagents:

- Recombinant TNF-α (0.5 µg in 200 µL PBS for i.p. injection).

- Rhodamine B-labeled dextran (70,000 MW) or PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD64 mAb for in vivo labeling.

- Anesthetics: Ketamine (125 mg/kg) and Xylazine (12.5 mg/kg).

- Procedure:

- Anesthetize the mouse with an i.p. injection of ketamine/xylazine.

- Perform a retro-orbital injection of 20 µL of Rhodamine B-dextran (10 mg/mL) to outline the microvasculature. For CD64 measurement, inject 100 µL of PE-anti-CD64 mAb (50 µg/mL) instead.

- For CD18 blockade experiments, co-inject 100 µg of CD18 blocking mAb with the dye.

- Fix the mouse on the stage of a multi-photon microscope. Use a 20x water immersion objective to image the microvasculature in the mouse ear.

- Perform line scanning on vessels with a diameter of 20-45 µm at ~650-850 Hz for 120 seconds to record traversing LysM-EGFP+ cells. This serves as the baseline (0 min) measurement.

- Administer TNF-α (0.5 µg in 200 µL PBS) or vehicle control via i.p. injection.

- Repeat the IVFC measurement at 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes post-injection.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze line scanning images with FIJI-ImageJ or custom Python code to determine cell diameter, traversing time, and vessel diameter.

- Count the number of fluorescent cells in each recording.

- Confirm cell identity and phenotype using conventional flow cytometry on blood, peritoneal lavage, and bone marrow samples collected at endpoint.

Protocol 2: Induction of Meconium Peritonitis in Neonatal Mice

This protocol describes a non-surgical model of sterile chemical peritonitis using human meconium, which is distinct from infectious sepsis models [18].

- Mouse Model: 4-day-old mouse pups (immunologically equivalent to human preterm infants).

- Key Reagents:

- Human Meconium Slurry (MS): Prepared from sterile meconium from healthy term newborns, suspended in PBS (500 mg/mL), and stored at -80°C.

- Procedure:

- Thaw an aliquot of stock MS and vortex before injection.

- Administer MS intraperitoneally to 4-day-old pups. The LD40 (dose causing 40% lethality) is established at 200 µL per pup. Doses between 100-300 µL can be used for dose-dependent studies.

- Monitor pups daily for health and survival for up to 7 days. Record body weights of survivors daily.

- For validation, subject MS to heat inactivation (70°C or 100°C for 15 min) prior to injection to denature digestive enzymes, which are the primary pathogenic agents.

- Endpoint Analyses:

- Hematology and Biochemistry: At 24 hours post-induction, collect blood via decapitation for complete blood counts (CBC) and analysis of hepatorenal function.

- Immunomodulatory Gene Expression: At 6 hours post-induction, harvest liver tissue, extract RNA, and perform PCR arrays to profile the expression of 84 genes related to innate and adaptive immune responses.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Mouse Peritonitis. This diagram illustrates the primary signaling cascades driving macrophage polarization and neutrophil recruitment in response to inflammatory stimuli like LPS and TNF-α, and their subsequent role in tissue repair and fibrosis [15] [17].

Diagram 2: IVFC Workflow for Neutrophil Dynamics. This workflow outlines the key steps for non-invasive monitoring of circulating myeloid cells in a live mouse model of peritonitis using intravital flow cytometry (IVFC) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Mouse Peritonitis Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Usage in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Induces robust immune response by binding to TLR4; used to establish inflammatory peritonitis. | i.p. injection at 10 mg/kg to induce systemic inflammation and transcriptomic changes in blood [5]. |

| Recombinant TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; used to induce neutrophil recruitment and sterile inflammation. | i.p. injection of 0.5 µg in 200 µL PBS to model TNF-α-driven peritonitis and neutrophil dynamics [17]. |

| LysM-EGFP Transgenic Mice | Genetically modified model where myeloid cells (neutrophils, macrophages) express EGFP for tracking. | Enables real-time IVFC monitoring and flow cytometric identification of circulating and infiltrating myeloid cells [17]. |

| CD18 Blocking Antibody | Inhibits neutrophil adhesion and extravasation; used to study recruitment mechanisms. | Retro-orbital injection of 100 µg to demonstrate the role of CD18 in neutrophil migration to the peritoneum [17]. |

| Human Meconium Slurry (MS) | Sterile, enzyme-rich slurry; induces chemical peritonitis distinct from live bacterial infection. | i.p. administration in neonatal mice (LD40 = 200 µL/pup) to model meconium peritonitis pathology [18]. |

| Fluorescent Conjugated Antibodies | Cell surface and intracellular staining for phenotyping via flow cytometry. | e.g., Anti-Ly6G (neutrophils), Anti-CD64 (activation), Anti-CD206 (M2 macrophages) [17]. |

| Rhodamine B-Dextran | High molecular weight fluorescent tracer; outlines blood vessels for IVFC. | Retro-orbital injection to visualize vasculature during line-scanning IVFC measurements [17]. |

Mouse peritonitis models are indispensable tools in biomedical research, serving as critical early in vivo screening systems for evaluating inflammatory responses and therapeutic efficacy of novel compounds [19] [20]. These models simulate the complex pathophysiology of peritoneal inflammation, enabling researchers to investigate innate immune mechanisms, leukocyte trafficking, and systemic inflammatory cascades. The historical significance of these models is profound, as the mouse peritonitis model was the first experimental animal system used in antibiotic research, demonstrating the efficacy of Prontosil and derivative sulphonamides against Streptococcus pyogenes in 1935 [19]. Since then, these models have evolved to encompass a diverse array of induction methods, each tailored to address specific research questions within immunology, infectious diseases, and drug development.

The utility of mouse peritonitis models stems from several practical advantages: they utilize small, cost-effective animals that are easy to maintain; they produce highly reproducible infections; and they offer straightforward experimental endpoints such as survival monitoring and bacterial quantification [20]. Furthermore, the ability to customize these models through various induction methods, mouse strains, and adjunctive agents makes them exceptionally versatile for studying different facets of inflammatory responses. This application note provides a comprehensive classification and methodological overview of the major mouse peritonitis models, detailing their applications, standardized protocols, and associated analytical approaches to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate system for their investigative needs.

Model Classifications and Comparative Analysis

Mouse peritonitis models can be broadly categorized based on the method of inflammatory induction. The table below summarizes the primary model classifications, their induction agents, key characteristics, and major research applications.

Table 1: Classification of Major Mouse Peritonitis Models

| Model Type | Inducing Agent | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications | Example Strains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Induction [21] [22] [5] | Zymosan, Thioglycollate, LPS | - Non-infectious, sterile inflammation- Highly reproducible & tunable- Peaks within hours | - Study of leukocyte recruitment & migration- Analysis of soluble mediator networks- Screening anti-inflammatory drugs | BALB/c, C57BL/6 |

| Bacterial Induction (Non-Resistant) [23] [24] | Live bacteria (e.g., E. coli, MRSA) | - Mimics natural infection- Allows bacterial load enumeration- Can progress to sepsis | - Evaluation of antimicrobial drug efficacy- Host-pathogen interaction studies- Vaccine research | Kunming, BALB/c |

| Bacterial Induction (Drug-Resistant) [25] [26] | Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, MRSA | - Models difficult-to-treat infections- Often requires virulence enhancers (e.g., mucin)- High mortality rate | - Testing novel antibiotics against MDR pathogens- PK/PD studies for last-resort drugs | BALB/c, ICR |

| Lethal Bacteremia Model [19] [20] | High virulence bacteria (e.g., S. pneumoniae) | - Naturally virulent in mice- Death/survival as primary endpoint- Does not require immunocompromised hosts | - Early-stage in vivo antibiotic screening- Determination of protective/curative doses | Various |

Analysis of Model Selection Criteria

The choice of a specific peritonitis model is dictated by the research objectives. For dissecting fundamental mechanisms of innate immunity and leukocyte biology, chemical induction models are ideal due to their sterility and reproducibility [21] [22]. The zymosan-induced model, for instance, is characterized by a rapid inflammatory response that peaks within a few hours and can be resolved, allowing for the study of both inflammation initiation and resolution phases [21].

When the goal is to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of therapeutic agents, bacterial induction models are more appropriate. For standard pathogens, standard models suffice [23], but for the critical pre-clinical testing of new antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms, specialized models that incorporate clinical isolates of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli or MRSA are essential [25] [24]. A key technical consideration for these models is the frequent use of virulence-enhancing agents. The addition of hog gastric mucin (typically at 3-4% concentration) is a well-established method to overcome the natural resistance of mice to many human pathogens, ensuring consistent and lethal infection necessary for robust therapeutic testing [25] [26] [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Zymosan-Induced Sterile Peritonitis

This protocol induces a sterile, acute inflammatory response, ideal for studying basic immunology and pharmacodynamics of anti-inflammatory compounds [21].

- Animals: Mice (e.g., C57BL/6), 6-8 weeks old.

- Reagents: Zymosan suspension in sterile saline (common doses: 1 mg or 10 mg per mouse) [21].

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Suspend zymosan in sterile, pyrogen-free saline. The concentration should be adjusted so the desired dose (e.g., 1 mg) is delivered in a volume of 200-500 µL.

- Induction: Anesthetize the mouse briefly using inhaled isoflurane. Using a 26-gauge needle, inject the zymosan suspension intraperitoneally (i.p.) in one of the lower abdominal quadrants to avoid internal organs.

- Monitoring: Monitor mice until fully recovered from anesthesia. The inflammatory response peaks within a few hours post-injection.

- Sample Collection: At the desired time point (e.g., 4-24h), euthanize the animal. Inject 5 mL of cold lavage buffer (e.g., HBSS containing 1-5% FBS or EDTA to prevent cell adherence) into the peritoneal cavity. Gently massage the abdomen and then aspirate the peritoneal wash fluid (PWF).

- Analysis: Centrifuge the PWF. The supernatant can be analyzed for cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, MIP-1a) by ELISA, and the cell pellet can be resuspended for leukocyte counting and differentiation by flow cytometry (e.g., identifying PMNs as CD115-Gr-1+ cells and macrophages as CD115+Gr-1- cells) [21].

Protocol 2: Bacterial Peritonitis with Hog Gastric Mucin

This protocol is designed for establishing a lethal infection with drug-resistant clinical isolates, crucial for antimicrobial efficacy testing [25] [26].

- Animals: 6-week-old female BALB/c or ICR mice [25].

- Reagents:

- Procedure:

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain to logarithmic phase in broth. Centrifuge and adjust the bacterial pellet to a concentration of ~1x10⁸ CFU/mL in PBS using spectrophotometry, verifying the count by plating.

- Mucin Preparation: Dissolve hog gastric mucin in PBS to make a 6% (w/v) solution. Sterilize appropriately (e.g., autoclaving).

- Inoculum Preparation: Immediately before injection, mix equal volumes of the adjusted bacterial suspension and the 6% mucin solution. The final challenge dose will be ~10⁷ CFU in 0.2 mL containing 3% mucin [25].

- Infection: Anesthetize mice with isoflurane. Inject the 0.2 mL inoculum intraperitoneally.

- Therapeutic Intervention: Administer the test compound or vehicle control at a predefined time post-infection (e.g., 1 hour) via an appropriate route (intravenous, subcutaneous, etc.).

- Endpoint Analysis: Monitor survival for up to 24-48 hours, checking every 12 hours. For bacterial burden assessment, collect blood via cardiac puncture or peritoneal lavage fluid at set times, serially dilute, and plate on agar to enumerate CFUs [23].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for establishing and analyzing a bacterial peritonitis model.

Protocol 3: LPS-Induced Peritonitis for Transcriptomic Studies

This model is used to study systemic gene expression changes in response to localized inflammation [5].

- Animals: Male C57BL/6 mice, 6-8 weeks old.

- Reagents: Lipopolysaccharide (LPS from E. coli).

- Procedure:

- Induction: Administer LPS (e.g., 10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection. Control mice receive sterile PBS.

- Sample Collection: At the designated time point (e.g., 1-4 hours), anesthetize mice and collect blood via retro-orbital bleeding or cardiac puncture into tubes containing anticoagulant.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Isolate total RNA from whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Perform bulk RNA sequencing. Subsequent bioinformatics analysis can identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and enriched pathways (e.g., NOD-like receptor, Toll-like receptor signaling) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of peritonitis studies requires a standardized set of core reagents and materials. The following table lists critical components for model establishment and analysis.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Mouse Peritonitis Models

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Inducers | Zymosan (from yeast) [21], Thioglycollate [22], Ultrapure LPS [5] | Induces sterile inflammation for studying leukocyte migration and mediator release. |

| Virulence Enhancer | Hog Gastric Mucin (Type III) [25] [26] [24] | Impairs host clearance mechanisms, enabling lethal infection with clinical bacterial isolates. |

| Bacterial Strains | Carbapenem-resistant E. coli, K. pneumoniae [25], MRSA (e.g., NRS71) [24] | Clinical isolates used to model difficult-to-treat human infections for antibiotic testing. |

| Assay Kits | ELISA Kits (for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, etc.) [21] | Quantifies cytokine and chemokine levels in peritoneal wash fluid or serum. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-mouse Ly6G (neutrophils), CD115, Gr-1, CCR3, Siglec-F [21] [17] | Identifies and quantifies infiltrating leukocyte populations (e.g., PMNs, macrophages, eosinophils). |

| Lavage & Culture Media | Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) [22], Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [25], Mueller-Hinton Broth [25] | Used for peritoneal lavage, bacterial culture, and as a vehicle/diluent for injections. |

Analytical Methods and Data Interpretation

A key strength of mouse peritonitis models is the breadth of analytical endpoints that can be measured to quantify the inflammatory response and therapeutic effects.

Cellular and Molecular Analysis

- Leukocyte Quantification: Peritoneal lavage fluid is the primary sample for analysis. Total and differential leukocyte counts are performed using automated hematology analyzers or, more precisely, by flow cytometry. Specific cell populations are identified using surface markers: PMNs as CD115-Gr-1+, macrophages as CD115+Gr-1-, and eosinophils as CCR3+Siglec-F+ [21]. Time-course studies show that total leukocyte infiltration peaks within hours of zymosan injection and declines thereafter [21].

- Cytokine and Chemokine Profiling: The supernatant from peritoneal wash fluid (PWF) or serum is analyzed using ELISA or multiplex immunoassays to measure the concentrations of key inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and MIP-1α [21]. These molecules drive the pathophysiology of peritonitis and are critical biomarkers for assessing the anti-inflammatory activity of test compounds.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Bulk RNA sequencing of blood or peritoneal cells from LPS-induced models can reveal global changes in gene expression. Studies have identified hundreds of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with upregulated pathways including NOD-like and Toll-like receptor signaling, and suppressed pathways involving T-cell receptor signaling and Th1/Th2 differentiation [5]. Advanced techniques like in vivo flow cytometry (IVFC) can non-invasively monitor the dynamics of circulating immune cells, such as LysM-EGFP+ neutrophils, in real-time during TNFα-induced peritonitis [17].

Outcome-Based Analysis

- Bacterial Enumeration: In infection models, the efficacy of an antimicrobial agent is directly assessed by quantifying the bacterial load. Samples of blood and peritoneal fluid are collected, serially diluted, plated on agar, and incubated to count the number of colony-forming units (CFU) [23] [24]. A successful treatment will show a significant reduction in CFU/mL compared to untreated controls.

- Survival Studies: For lethal models, the survival rate over a defined period (e.g., 24-48 hours) is a primary, unambiguous endpoint. Data are often presented using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and statistical comparisons (e.g., Log-rank test) determine the significance of a treatment's protective effect [25] [24]. The 50% effective dose (ED₅₀) of a drug can be calculated from such studies [19].

The signaling pathways activated in peritonitis are complex. The following diagram summarizes the key pathways and cellular responses identified through transcriptomic and molecular analyses.

Mouse models of peritonitis are indispensable tools for investigating the pathophysiology of inflammatory responses and evaluating potential therapeutic interventions. The choice of a specific model is crucial, as it must accurately reflect the research objectives, whether related to infectious peritonitis, sterile chemical inflammation, or the complex interplay between metabolism and immunity. This application note provides a structured comparison of established murine peritonitis models, detailed protocols for their implementation, and guidance for matching scientific questions to the appropriate experimental system.

Selecting the correct peritonitis model is the first critical step in designing a scientifically sound experiment. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of four commonly used models to aid in this selection process.

Table 1: Characteristics of Different Mouse Peritonitis Models

| Model Name | Primary Induction Method | Type of Inflammation | Key Research Applications | Key Inflammatory Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cecal Slurry (CS) Model [9] | Intraperitoneal injection of cecal content suspension | Polymicrobial Sepsis, Infectious | Sepsis pathophysiology, antibiotic efficacy testing, immune responses to live bacteria | Survival rates, bacterial load (CFU), plasma cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), hematological parameters [9] |

| Meconium Slurry (MS) Model [9] | Intraperitoneal injection of human meconium | Sterile, Chemical Peritonitis | Neonatal meconium peritonitis, sterile inflammatory cascades, digestive enzyme-mediated pathology | Survival rates, histopathology of peritoneal organs, serum biochemistry (liver/kidney function), inflammatory gene expression (PCR array) [9] |

| Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) [27] | Surgical ligation and puncture of the cecum | Polymicrobial Sepsis, Infectious | Gold-standard for sepsis and septic shock, drug efficacy, immune cell recruitment and function | Cytokine levels in lavage fluid (ELISA), lung injury (histology), immune cell phenotyping, organ failure assessment [27] |

| Hog Gastric Mucin Model [26] | Intraperitoneal co-injection of bacteria with mucin | Monomicrobial, Infectious | Pathogenesis studies of specific clinical isolates (e.g., carbapenem-resistant bacteria), virulence studies | Survival rates, bacterial load (CFU), efficacy of antimicrobial agents [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Meconium-Induced Sterile Peritonitis Model

This protocol generates a neonatal mouse model that closely reflects the pathology of human meconium peritonitis, a life-threatening condition in the perinatal period [9].

A. Reagent Preparation

- Human Meconium Slurry (MS) Stock Solution:

- Collection: Aseptically collect fresh meconium from healthy term human newborns with parental consent.

- Preparation: Add 1.0 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per 500 mg of meconium (500 mg/mL concentration).

- Homogenization: Stir the mixture vigorously and aspirate through a 23-gauge needle.

- Storage: Aliquot into cryovials and store at -80°C.

- Sterility Check: Before use, thaw an aliquot and plate 50 µL on brain/heart infusion (BHI) agar. Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours. Use only stocks with no bacterial growth [9].

B. Animal Model Induction

- Animals: Use 4-day-old mouse pups (e.g., FVB/NJcl strain), which are immunologically equivalent to human preterm infants.

- Injection: Administer the MS stock solution intraperitoneally at a defined dose (e.g., an LD40 of 200 µL per pup).

- Monitoring: Monitor pups daily for health and survival for up to 7 days. Record body weights of survivors daily beginning 24 hours post-injection [9].

C. Data Collection and Analysis

- Survival Analysis: Monitor and record survival rates for 7 days.

- Sample Collection: At desired endpoint (e.g., 24 hours post-induction), sacrifice pups and collect blood via decapitation.

- Hematology & Biochemistry: Perform complete blood counts (CBC) and analyze serum for hepatorenal function markers.

- Molecular Analysis: Extract RNA from tissues (e.g., liver) for PCR array analysis of immunomodulatory gene expression [9].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for establishing and analyzing the meconium peritonitis model.

Protocol: Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) Model

The CLP model is a widely accepted gold standard for studying polymicrobial sepsis and subsequent inflammatory responses [27].

A. Pre-Surgical Preparation

- Animals: Anesthetize mice (e.g., 8-12 week old) via isoflurane inhalation.

- Asepsis: Shave and disinfect the abdominal area.

B. Surgical Procedure

- Incision: Make a midline abdominal incision (approximately 1.5 cm).

- Exteriorization: Gently exteriorize the cecum.

- Ligation: Ligate the cecum below the ileocecal valve without causing intestinal obstruction.

- Puncture: Puncture the ligated cecum once with a 22-gauge needle.

- Replacement: Gently squeeze a small amount of feces through the puncture to ensure patency, then replace the cecum into the abdominal cavity.

- Closure: Close the abdominal wall in layers [27].

C. Post-Operative Care

- Resuscitation: Administer 0.3 mL of saline subcutaneously immediately after surgery.

- Monitoring: Return mice to their cages with free access to food and water; monitor closely.

D. Sample Collection and Analysis

- Peritoneal Macrophage Isolation:

- Elicit macrophages by injecting 3 mL of 3% thioglycollate broth intraperitoneally 3-4 days prior.

- Harvest cells by lavaging the peritoneal cavity with DMEM.

- Plate adherent cells for in vitro assays [27].

- Cytokine Measurement: Collect peritoneal lavage fluid and analyze cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) by ELISA [27].

- Histopathology: Inflate and fix lungs with 4% paraformaldehyde for H&E staining to assess injury [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents used in peritonitis research, along with their specific functions and application contexts.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Peritonitis Research

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Hog Gastric Mucin | Virulence-enhancing factor; inhibits bacterial clearance | Used at 3% concentration mixed with bacterial inoculum to establish monomicrobial infection with clinical isolates [26]. |

| Thioglycollate Broth | Inflammatory eliciting agent | Injected intraperitoneally (3%, w/v) to recruit macrophages for harvesting and subsequent in vitro studies [27]. |

| Lenalidomide | IKZF1 transcription factor inhibitor | Used in CLP models to investigate mechanisms of macrophage-mediated inflammation, e.g., administered to attenuate inflammatory response [27]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic solution for dilutions and lavage | Used as a diluent for meconium slurry preparation and for peritoneal lavage to collect immune cells [9] [27]. |

| Collagenase I | Enzyme for tissue digestion | Used to enzymatically digest the omentum to create single-cell suspensions for single-cell RNA sequencing analysis [28]. |

Signaling Pathways in Peritonitis

Understanding the molecular pathways driving inflammation is key to developing targeted therapies. Recent research highlights the role of the IKZF1/HDAC3-SDHB-succinate axis in macrophage hyperactivation during CLP-induced peritonitis [27].

The following diagram illustrates this key signaling pathway identified in macrophage hyperactivation during peritonitis.

Pathway Description: In macrophages during CLP-induced peritonitis, inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS) lead to upregulation of the transcription factor IKZF1. IKZF1 recruits histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to the promoter of SDHB, a key subunit of mitochondrial complex II. This recruitment results in SDHB deacetylation and subsequent repression of its expression. The loss of SDHB disrupts the mitochondrial electron transport chain, causing succinate accumulation, elevated ROS, and reduced ATP. This metabolic dysfunction amplifies the pro-inflammatory response, leading to increased production of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, and ultimately exacerbating tissue injury, such as in the lungs [27].

Establishing Robust Protocols: From Infectious Agents to Non-Infectious Inducers

Mouse models of peritonitis are indispensable tools for studying the pathophysiology of sepsis and systemic inflammatory responses. Among these, Fecal-Induced Peritonitis (FIP) and Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) represent two widely utilized polymicrobial sepsis models that closely mimic human intra-abdominal infections. These models facilitate the investigation of complex immune pathways, organ dysfunction, and potential therapeutic interventions in a controlled laboratory setting. The FIP model involves the direct intraperitoneal injection of a standardized fecal slurry, creating a reproducible polymicrobial challenge [29]. In contrast, the CLP model combines tissue ischemia and bacterial leakage through surgical ligation and puncture of the cecum, generating a more gradual onset of peritonitis [30] [31]. Both models trigger a systemic inflammatory response characterized by cytokine release, immune cell activation, and eventual organ failure, providing critical platforms for evaluating inflammatory mechanisms and treatment strategies. This protocol outlines standardized methodologies for both approaches, emphasizing practical implementation within the context of preclinical sepsis research.

Model Comparison and Selection

The choice between FIP and CLP depends on the specific research objectives, technical expertise, and desired disease progression characteristics. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these models to guide appropriate experimental selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of FIP and CLP Murine Sepsis Models

| Feature | Fecal-Induced Peritonitis (FIP) | Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Intraperitoneal injection of prepared fecal slurry [29] | Surgical ligation and puncture of the cecum [30] [31] |

| Inflammatory Drivers | Polymicrobial infection without significant tissue necrosis [29] | Polymicrobial infection combined with ischemic/necrotic tissue [30] |

| Key Advantages | High reproducibility; less operator-dependent; minimal surgical trauma; easily standardized for multi-laboratory studies [29] | Clinically relevant progression; includes an ischemic tissue component; established as a gold standard for polymicrobial sepsis [30] [31] |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate (requires slurry preparation) | High (requires survival surgery and aseptic technique) |

| Disease Onset | Rapid, acute | More gradual, subacute |

| Severity Control | Modulating fecal slurry dose (e.g., 0.5-2.5 mg/g) [29] [32] | Modulating ligation length (>1 cm for high severity) and needle gauge (e.g., 19G-27G) [30] [31] |

| Typical Mortality | Adjustable with dose (e.g., 60-89% with 0.75 mg/g) [29] [32] | Adjustable with technique (e.g., 55-100% with 19G needle and long ligation) [31] |

| Recommended Applications | High-throughput therapeutic screening, immunology studies, multi-center trials [29] | Studies of sepsis with ischemic component, long-term survival, and therapeutic timing [30] |

Critical parameters from published studies utilizing these models are consolidated below to inform experimental design and expectation of outcomes.

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Data from Preclinical Studies

| Study Focus | Model & Parameters | Key Quantitative Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Development & Multi-lab Variation | FIP (Fecal Slurry: 0.75 mg/g) | • Mortality: 60% (Site 1) vs. 88% (Site 2)• Early Antibiotics (4h): 100% survival• Late Antibiotics (12h): Significant mortality | [29] |

| Aging and Sepsis Susceptibility | FIP (0.75 mg/g in young vs. aged mice) | • Mortality: 42% (Young) vs. 89% (Aged)• Aged mice exhibited increased inflammation and lung injury | [32] |

| Technical Severity Modulation in CLP | CLP (Ligation length and needle size) | • Ligation >1 cm: ~100% mortality in <3 days• Needle 19G (2 punctures): 55-60% survival• Needle 22G: 100% survival | [31] |

| Scoring and Prediction | FIP (90 mg/mL slurry concentration) | • MSS ≥ 3: 100% specificity for predicting death within 24h• Mortality: 75% at 24 hours | [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Fecal-Induced Peritonitis (FIP) Model

Fecal Slurry Preparation

- Source Material: Collect fresh cecal contents from donor animals (e.g., rats or mice) immediately after euthanasia [29] [33].

- Homogenization: Weigh the cecal contents and homogenize in phosphate buffer (e.g., 6 mL/g of content) [29]. Alternatively, normal saline can be used to achieve concentrations of 45-180 mg/mL [33].

- Filtration and Centrifugation: Filter the homogenate through a 70-100 μm cell strainer to remove large particulate matter [29] [33]. Centrifuge the filtered solution at 3000 × g for 25 minutes at 4°C [29].

- Aliquoting and Storage: Resuspend the pellet in a 5% dextrose solution with 10% glycerol to a final concentration of 100 mg/mL. Aliquot (e.g., 1 mL per tube) and store at -80°C [29].

Induction of Sepsis

- Animals: Use 8-13 week old C57BL/6 mice. Acclimatize for at least one week prior to experimentation [29] [32].

- Injection: Thaw an aliquot of slurry and warm to room temperature. Under light isoflurane anesthesia, administer the slurry via intraperitoneal (IP) injection into the lower abdominal quadrant using a 25-gauge needle [29]. The dose should be calculated based on body weight (e.g., 0.75 mg/g for a mid-range mortality model) [29] [32].

- Controls: Inject control mice with the vehicle solution (5% dextrose with 10% glycerol) only [29].

Post-Procedural Care

- Supportive Care: Provide fluid resuscitation with subcutaneous Ringer's lactate (e.g., 200 μL) [29]. Place heating blankets or pads beneath half the cage to allow thermoregulation [29] [32].

- Analgesia: Administer subcutaneous buprenorphine (e.g., 0.01 mg/kg) at 4 hours post-procedure and every 8-12 hours thereafter [29].

- Antibiotics: To mimic clinical practice, administer antibiotics (e.g., piperacillin-tazobactam or imipenem) subcutaneously or IP, typically starting at 12 hours post-FIP induction [29] [32].

Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) Model

Surgical Procedure

- Anesthesia: Induce surgical anesthesia with inhaled isoflurane (3.5-4.5%) or an injectable cocktail like ketamine/xylazine (75/15 mg/kg, IP) [30] [31].

- Preparation: Shave and aseptically prepare the abdominal skin with alternating betadine and 70% alcohol scrubs [30] [31].

- Laparotomy: Perform a 1-2 cm midline incision through the skin and abdominal wall to expose the cecum [30] [31].

- Ligation: Gently exteriorize the cecum. Identify the ileocecal valve and ligate 50-75% of the cecum (approximately 1 cm from the cecal tip) using a 4-0 or 5-0 silk suture, ensuring not to cause intestinal obstruction [30] [31].

- Puncture: Puncture the ligated cecum once with a 19-27 gauge needle. Gently squeeze the cecum to extrude a small amount of fecal material (approximately 1 mm bead) through the puncture site [30] [31].

- Closure: Return the cecum to the peritoneal cavity. Close the abdominal muscle layer with absorbable sutures (e.g., Vicryl) and the skin with wound clips or non-absorbable sutures [30] [31].

- Sham Control: For sham-operated controls, perform the identical procedure including exteriorization of the cecum, but omit the ligation and puncture [30].

Post-Operative Care

- Resuscitation: Immediately after surgery, administer 1 mL of pre-warmed sterile saline subcutaneously [31].

- Analgesia: Provide post-operative analgesia with subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.05-0.2 mg/kg) every 8-12 hours for at least 24 hours [30] [31].

- Supportive Care: Place animals on a heating pad or under a heat lamp until fully recovered from anesthesia. Provide hydrogel and standard chow ad libitum on the cage floor [31].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key decision points and procedures for both the FIP and CLP models.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for FIP and CLP models, highlighting key procedural steps and post-operative care.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for FIP and CLP Models

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Model | Mouse Strain | C57BL/6 (8-12 weeks old) [29] [33] | Standardized genetic background for reproducible immune responses. |

| Anesthesia & Analgesia | Isoflurane | 3.5-4.5% for induction, 1.5-2% for maintenance [30] | Provides stable and reversible surgical anesthesia. |

| Buprenorphine | 0.05-0.2 mg/kg, subcutaneously, q12h [30] [31] | Opioid analgesic for post-operative pain management. | |

| Surgical Materials (CLP) | Suture | 4-0 or 5-0 Silk for cecal ligation [30] [31] | Provides secure ligation of the cecum. |

| Needles | 19-27 gauge for cecal puncture [30] [31] | Controls severity of peritonitis; larger gauge increases lethality. | |

| Wound Clips | 7mm auto-clips [31] | For rapid and consistent skin closure. | |

| Supportive Care | Fluids | Sterile 0.9% Saline or Ringer's Lactate [29] [31] | Fluid resuscitation to counter hypovolemia. |

| Antibiotics | Piperacillin-Tazobactam or Imipenem [29] | Mimics clinical standard of care; timing affects outcomes. | |

| Assessment Tools | Murine Sepsis Score (MSS) | 7-parameter clinical score [33] | Standardized metric for monitoring sepsis severity and predicting outcomes. |

Assessment and Analytical Methods

Clinical Scoring: Murine Sepsis Score (MSS)

The Murine Sepsis Score is a validated clinical assessment tool for monitoring disease progression, with high specificity for predicting mortality [33]. The system evaluates seven parameters: spontaneous activity, response to touch, response to auditory stimulus, posture, respiration rate, respiration quality, and appearance (piloerection). Each parameter is scored from 0 (normal/healthy) to 4 (severely compromised), generating a cumulative score. An MSS ≥ 3 has 100% specificity for predicting death within 24 hours, providing a robust, ethically sound endpoint for intervention or euthanasia [33].

Sample Collection and Analysis

- Blood Collection: Terminal blood collection via cardiac puncture under anesthesia is standard. Plasma/serum can be analyzed for:

- Peritoneal Lavage: Collect by injecting and retrieving sterile PBS from the peritoneal cavity. Analyze for immune cell populations (flow cytometry), cytokine levels, and bacterial load [29] [4].

- Tissue Harvest: Harvest organs (e.g., liver, lungs, spleen, kidney) for:

- Histopathology: Fix in formalin for H&E staining to assess inflammation and damage [4] [33].

- Bacterial Load: Homogenize tissues and plate serial dilutions on agar to quantify Colony Forming Units (CFU) [29] [33].

- Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Assay: Quantifies neutrophil infiltration in tissues [31].

- Gene/Protein Expression: RNA/protein extraction for PCR, western blot, or other molecular analyses [4].

The FIP and CLP models are robust and complementary systems for investigating peritonitis and systemic inflammation. The FIP model offers superior standardization and is ideal for high-throughput studies of immune responses and therapeutic efficacy, while the CLP model provides high clinical relevance with its combination of infection and ischemia. Adherence to the detailed protocols for model induction, post-procedural care, and objective assessment using tools like the MSS is paramount for generating valid, reproducible, and ethically conducted preclinical data. Mastery of these models provides a powerful foundation for advancing our understanding of sepsis and evaluating novel anti-inflammatory strategies.