Nuclear Fraction Isolation for NF-κB Translocation Assays: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to nuclear fraction isolation techniques specifically optimized for NF-κB translocation assays.

Nuclear Fraction Isolation for NF-κB Translocation Assays: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to nuclear fraction isolation techniques specifically optimized for NF-κB translocation assays. Covering foundational principles through advanced applications, we detail traditional fractionation protocols and cutting-edge imaging methods that enable precise quantification of NF-κB subcellular localization. The content addresses critical troubleshooting scenarios for common isolation challenges and offers systematic validation approaches to ensure assay reliability. By comparing method advantages and limitations across different research contexts, this resource serves as an essential reference for studying NF-κB signaling in immune response, inflammation, and disease mechanisms, with direct relevance to drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Understanding NF-κB Biology and Translocation Fundamentals

Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) represents a family of transcription factors that serve as master regulators of inducible gene expression in eukaryotic cells. First identified in 1986 as a nuclear protein binding to the immunoglobulin kappa light chain enhancer in B cells, NF-κB has since been established as a pivotal controller of diverse cellular processes including immune responses, inflammation, cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [1] [2]. The NF-κB pathway is characterized by its rapid-response capability, allowing cells to quickly adapt to environmental stimuli such as pathogens, stress signals, and inflammatory cytokines without requiring new protein synthesis [1].

NF-κB signaling has direct screening applications for drug discovery across multiple therapeutic areas, most notably inflammatory diseases and cancer [3]. In pathological conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, hematological malignancies, and triple-negative breast cancer, dysregulated NF-κB activation drives disease progression through persistent expression of pro-inflammatory mediators and anti-apoptotic factors [2] [4]. Consequently, measuring NF-κB activation, particularly through nuclear translocation assays, has become an essential methodology for both basic research and pharmaceutical development.

Structural Diversity of NF-κB Family Members

Classification and Domain Architecture

The mammalian NF-κB family comprises five structurally related proteins categorized into two distinct classes based on their structural features and processing requirements [1] [5]:

Class I: Precursor Proteins

- NF-κB1 (p105/p50): Synthesized as the p105 precursor that undergoes proteasomal processing to generate the mature p50 subunit.

- NF-κB2 (p100/p52): Synthesized as the p100 precursor that undergoes regulated processing to produce the mature p52 subunit.

Class II: Transactivating Subunits

- RelA (p65): Contains a C-terminal transactivation domain.

- RelB: Contains a C-terminal transactivation domain and requires an N-terminal leucine zipper for full activity.

- c-Rel: Contains a C-terminal transactivation domain.

All NF-κB family members share a conserved approximately 300-amino acid Rel homology domain (RHD) at their N-terminus [5] [6]. This domain mediates several critical functions including DNA binding, dimerization between family members, interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins, and contains the nuclear localization signal (NLS) that controls subcellular trafficking [5]. The structural diversity beyond the RHD determines the functional specificity of each subunit, particularly regarding their transcriptional activation potential.

Comparative Structural and Functional Features

Table 1: Structural and Functional Properties of NF-κB Family Members

| Protein | Precursor | Transactivation Domain | DNA Binding | Key Dimerization Partners | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p50 | p105 | No | Yes | p65, c-Rel, p50 | Transcriptional repression as homodimer; activation as heterodimer |

| p52 | p100 | No | Yes | RelB, p65 | Lymphoid organ development; B-cell maturation |

| RelA (p65) | None | Yes | Yes | p50, p52, c-Rel | Primary transcriptional activator; inflammatory responses |

| RelB | None | Yes | Yes | p50, p52 | Non-canonical pathway; lymphoid organogenesis |

| c-Rel | None | Yes | Yes | p50, p65 | Immune cell proliferation; anti-apoptotic genes |

The Class II subunits (RelA, RelB, and c-Rel) contain C-terminal transactivation domains (TADs) that enable them to directly activate transcription of target genes [5] [6]. In contrast, the Class I subunits (p50 and p52) lack intrinsic transactivation capacity and primarily function as DNA-binding components that must heterodimerize with TAD-containing partners to activate transcription [1]. When forming homodimers, p50 and p52 can actually repress transcription by competing for κB binding sites or recruiting transcriptional repressors [5].

The NF-κB dimerization repertoire is extensive, with up to 15 different homo- and heterodimeric combinations possible [5]. The p50-RelA heterodimer represents the most abundant and well-characterized combination, found in almost all cell types and often referred to as "canonical" NF-κB [5]. Different dimer combinations exhibit preferences for specific κB binding sites and regulate distinct subsets of genes, providing a layer of regulatory specificity to the NF-κB response [5].

NF-κB Signaling Pathways

NF-κB activation occurs primarily through two distinct signaling cascades—the canonical and non-canonical pathways—that respond to different extracellular stimuli and regulate specific aspects of immune function and development [2] [6]. Both pathways ultimately control the subcellular localization of NF-κB dimers by regulating their release from inhibitory proteins.

The Canonical NF-κB Pathway

The canonical pathway is activated by a diverse array of stimuli including pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (LPS, viral RNA), and antigen receptor engagement [2] [6]. This pathway centers on the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, composed of two catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit NEMO/IKKγ [1] [2].

The activation mechanism involves:

- Receptor Proximal Signaling: Ligand binding to receptors (TNFR, TLR, TCR/BCR) recruits adaptor proteins (TRADD, TRAF, CARD) that ultimately activate the kinase TAK1 [2].

- IKK Complex Activation: TAK1 phosphorylates IKKβ within the IKK complex, enhancing its kinase activity [2].

- IκB Phosphorylation and Degradation: Activated IKK phosphorylates IκBα at specific serine residues (Ser32/Ser36), targeting it for K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [1] [2].

- Nuclear Translocation: Degradation of IκBα exposes the nuclear localization sequence on NF-κB dimers (typically p50-RelA), allowing their import into the nucleus via the importin-α/β system [2].

- Target Gene Activation: Nuclear NF-κB dimers bind to κB enhancer elements (consensus: 5′-GGGRNWYYCC-3′) and recruit co-activators such as CBP/p300 to initiate transcription of target genes [2].

The canonical pathway operates rapidly, with NF-κB nuclear translocation typically occurring within minutes of stimulation [3]. This pathway primarily activates p50-RelA heterodimers and regulates genes involved in immediate inflammatory and immune responses [6].

The Non-Canonical NF-κB Pathway

The non-canonical pathway responds to a more limited set of stimuli including lymphotoxin-β, B-cell activating factor (BAFF), and CD40 ligand [6]. This pathway functions independently of NEMO/IKKγ and instead relies on NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) and IKKα homodimers [2] [6].

Key steps in non-canonical activation include:

- NIK Stabilization: Receptor engagement prevents NIK degradation, allowing its accumulation.

- IKKα Activation: NIK phosphorylates and activates IKKα homodimers.

- p100 Processing: Activated IKKα phosphorylates p100, triggering its partial proteasomal processing to p52.

- Nuclear Translocation: The processing liberates RelB-p52 heterodimers for nuclear translocation.

The non-canonical pathway operates with slower kinetics (hours rather than minutes) and is particularly important for lymphoid organ development, B-cell maturation, and adaptive immunity [2] [6].

Methodologies for NF-κB Translocation Analysis

The critical step of NF-κB activation—nuclear translocation—can be quantified using multiple methodological approaches. The choice of technique depends on the specific research requirements, including throughput needs, quantitative precision, and available instrumentation.

Comparative Analysis of NF-κB Translocation Assays

Table 2: Methodologies for Assessing NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

| Method | Principle | Key Output Parameters | Throughput | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immuno-fluorescence Microscopy | Fluorescent antibody staining of p65 and nuclear counterstain | Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio; Translocation difference | Medium | Single-cell resolution; Accessible instrumentation | Lower throughput; Operator-dependent analysis |

| High-Content Screening (HCS) | Automated fluorescence microscopy with computational image analysis | Multiple translocation metrics; Morphological parameters | High | High-content data; Statistical robustness | Specialized equipment; Complex optimization |

| ImageStream Cytometry | Flow cytometry with imaging capability | Similarity score (pixel correlation coefficient) | High | Large cell numbers; Objective quantification | Specialized instrument requirement |

| Western Blot (Nuclear Fractions) | Subcellular fractionation with immunodetection | Nuclear p65 protein levels | Low | Protein size confirmation; Familiar technique | No single-cell resolution; Population average only |

| Gel Shift Assay (EMSA) | Electrophoretic mobility shift of nuclear extracts | DNA-binding activity | Low | Functional assessment of DNA binding | Radioactive materials; Technical complexity |

Detailed Protocol: Quantitative NF-κB Translocation Assay Using Immunofluorescence and Image Analysis

This protocol adapts methodology from multiple sources [3] [7] [8] to provide a robust approach for quantifying NF-κB nuclear translocation in adherent cell cultures.

Cell Culture and Stimulation

- Cell Preparation: Plate appropriate cell type (e.g., primary macrophages, HeLa cells) on glass coverslips at 2×10^5 cells/coverslip and culture until 60-80% confluent.

- Stimulation: Treat cells with NF-κB activator (e.g., TNF-α at 10-50 ng/mL, IL-1α at 10-50 ng/mL, or LPS at 100 ng/mL - 1 μg/mL) for predetermined optimal time (typically 15-45 minutes).

- Inhibition Controls: Include control samples pre-treated with NF-κB pathway inhibitors (e.g., IKK inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors) for 1-2 hours prior to stimulation.

- Fixation: Immediately fix cells with 3.7-4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

Immunofluorescence Staining

- Permeabilization: Incubate fixed cells with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Blocking: Apply blocking buffer (3-10% serum in PBS) for 30-60 minutes to reduce non-specific binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with anti-RelA/p65 antibody (e.g., Santa Cruz C-20, 1:50-1:200 dilution) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Apply fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 546, or 633, 1:200-1:1000 dilution) for 45-60 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Nuclear Counterstaining: Incubate with DNA stain (DAPI, Hoechst, or DRAQ5) for 5-10 minutes.

- Mounting: Mount coverslips on glass slides using anti-fade mounting medium.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

- Image Capture: Acquire fluorescence images using confocal or widefield fluorescence microscopy with consistent exposure settings across samples.

- Nuclear Segmentation: Create binary mask from nuclear stain channel to define nuclear regions of interest (ROI).

- Cytoplasmic Definition: Subtract nuclear mask from cell mask (defined by p65 staining or brightfield) to generate cytoplasmic ROI.

- Intensity Quantification: Measure mean fluorescence intensity in nuclear and cytoplasmic ROIs for each cell.

- Translocation Calculation: Compute translocation metrics:

- Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (Nuc/Cyt Ratio)

- Difference metric (Cyto-Nuc Difference)

- Similarity score (pixel correlation coefficient between p65 and nuclear stain)

Validation and Quality Control

- Positive Controls: Include TNF-α-stimulated cells as positive translocation control.

- Negative Controls: Include unstimulated cells and isotype control antibodies.

- Specificity Controls: Verify specificity with siRNA knockdown or inhibitor treatments.

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze minimum of 200-500 cells per condition across multiple biological replicates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NF-κB Translocation Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NF-κB Translocation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Stimuli | TNF-α, IL-1α/β, LPS, Pam3CSK4 | Induce canonical NF-κB pathway activation | Titrate concentration for optimal response |

| Pathway Inhibitors | IKK inhibitors (e.g., BAY-11-7082), Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) | Block NF-κB activation; Negative controls | Confirm specificity for interpretation |

| Primary Antibodies | Anti-RelA/p65 (e.g., Santa Cruz C-20), Anti-p50, Anti-phospho-p65 | Detect NF-κB subunits and activation states | Validate for immunofluorescence applications |

| Secondary Antibodies | Fluorophore-conjugated (e.g., Alexa Fluor series) | Signal amplification and detection | Match to microscope filter sets |

| Nuclear Stains | DAPI, Hoechst 33342, DRAQ5 | Nuclear segmentation and localization reference | Consider compatibility with fixation |

| Cell Lines | HeLa, THP-1, Primary macrophages | Model systems for NF-κB studies | Primary cells may show donor variability |

| Contezolid | Contezolid, CAS:1112968-42-9, MF:C18H15F3N4O4, MW:408.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MX1013 | MX1013 (Z-VD-fmk)|Potent Caspase Inhibitor | MX1013 is a potent, irreversible dipeptide pan-caspase inhibitor for apoptosis research. This product is for research use only and is not intended for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Therapeutic Targeting

The quantitative assessment of NF-κB nuclear translocation has become increasingly important in drug discovery and development, particularly for diseases characterized by dysregulated NF-κB signaling.

High-Throughput Screening Applications

Advanced image analysis algorithms enable high-content screening for modulators of NF-κB translocation [3] [9]. These systems can automatically extract multiple translocation parameters including:

- Number of translocation peaks within a time course

- Time to reach peak nuclear localization

- Amplitude of each translocation event

- Oscillation kinetics in single cells

Such detailed kinetic profiling allows identification of compounds that subtly modulate NF-κB dynamics rather than simply inhibiting or activating the pathway, providing more sophisticated intervention strategies [9].

Therapeutic Targeting of NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

Recent advances in NF-κB targeted therapies include the development of specific inhibitors that prevent nuclear translocation rather than upstream signaling events. For example, the small molecule CRL1101 was designed to bind specifically to RelA and disrupt its nuclear localization signal, thereby sequestering NF-κB in the cytoplasm [4]. This approach has shown promising results in triple-negative breast cancer models, where constitutive NF-κB activation drives tumor growth and therapy resistance [4].

The strategy of blocking nuclear translocation of transcription factors represents a novel approach in cancer drug development that may overcome limitations associated with upstream pathway inhibitors while maintaining specificity compared to broad-acting anti-inflammatory agents.

The NF-κB transcription factor family exemplifies the sophisticated integration of structural diversity and functional specialization in cellular signaling systems. The distinct composition of NF-κB dimers, coupled with their regulation through multiple activation pathways, enables precise control over diverse gene expression programs fundamental to immune function, inflammation, and cell survival.

Methodologies for quantifying NF-κB nuclear translocation, particularly advanced imaging approaches, continue to evolve toward higher throughput, greater quantitative precision, and single-cell resolution. These technical advances, combined with growing understanding of NF-κB structural biology, are enabling new therapeutic strategies that target specific aspects of NF-κB regulation. As research continues to unravel the complexity of NF-κB signaling networks, the measurement of nuclear translocation remains a cornerstone methodology for both basic research and drug discovery applications focused on this pivotal transcriptional regulatory system.

The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) family of transcription factors serves as a critical regulator of immune responses, inflammation, cell survival, and proliferation. The canonical (or classical) NF-κB pathway is a prototypical proinflammatory signaling pathway activated by diverse stimuli including proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-1 (IL-1), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) like bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement [10] [11] [12]. This pathway is characterized by the rapid, inducible nuclear translocation of specific NF-κB dimers, predominantly the p50/RelA heterodimer, which controls the expression of genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and anti-apoptotic factors [10] [11]. Given its central role in inflammation and immunity, precise measurement of NF-κB nuclear translocation through nuclear fraction isolation is fundamental for research in immunology, cancer biology, and drug development.

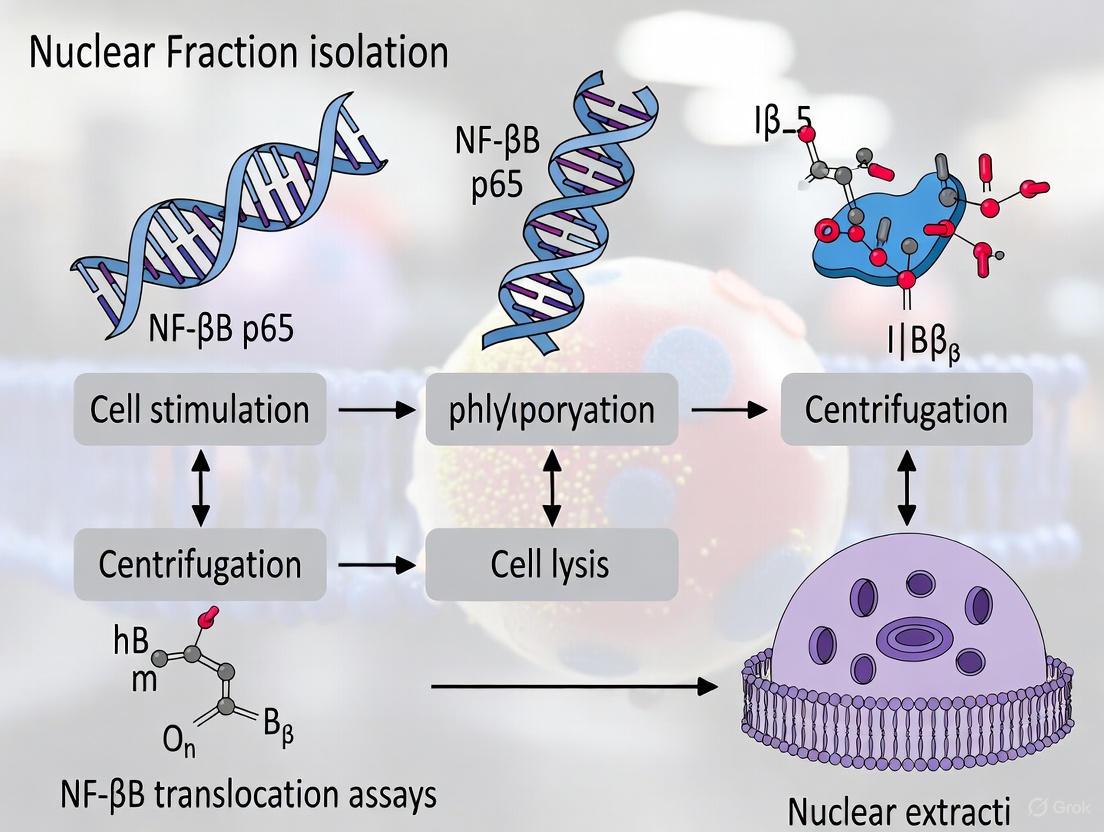

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the canonical NF-κB activation pathway, from receptor stimulation to target gene transcription:

Key Molecular Events in Canonical NF-κB Activation

Cytoplasmic Sequestration and IKK Complex Activation

In unstimulated cells, NF-κB dimers (primarily p50/RelA) are sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory proteins of the IκB family, with IκBα being the major inhibitor [10] [11]. The IκB proteins mask the nuclear localization signals (NLS) of NF-κB proteins through their ankyrin repeat domains, preventing nuclear translocation and maintaining the transcription factor in an inactive state [1] [10]. Upon cellular stimulation through receptors such as TNFR, IL-1R, or TLRs, a signaling cascade is triggered that converges on activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex [11] [12]. This complex consists of two catalytic subunits, IKKα (IKK1) and IKKβ (IKK2), and a regulatory subunit IKKγ (NEMO) [10] [11]. For canonical signaling, IKKβ and NEMO are essential, while IKKα plays a minor role [11].

IκBα Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and Degradation

Activated IKK complex phosphorylates IκBα at two critical N-terminal serine residues (Ser32 and Ser36 in human IκBα) [10] [11]. This phosphorylation event serves as a recognition signal for E3 ubiquitin ligases, which then conjugate lysine-linked polyubiquitin chains to IκBα [1]. The ubiquitinated IκBα is subsequently targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome [10] [11]. This degradation process is rapid and typically occurs within minutes of stimulation, representing a critical point of regulation in the canonical pathway.

NF-κB Nuclear Translocation and DNA Binding

With the degradation of IκBα, the NF-κB dimers are freed from cytoplasmic retention and their nuclear localization signals are exposed. The liberated NF-κB complexes, predominantly p50/RelA, then translocate to the nucleus through the nuclear pore complex [13] [1]. Once in the nucleus, these dimers bind to specific DNA sequences known as κB enhancer elements (with a consensus sequence of 5'-GGGRNWYYCC-3') in the regulatory regions of target genes [14]. The p50 subunit is responsible for DNA binding, while the RelA subunit contains a transactivation domain that recruits transcriptional co-activators and the basal transcription machinery to initiate gene expression [1] [10].

Quantitative Data of Canonical NF-κB Activation

Table 1: Key Temporal and Structural Parameters of Canonical NF-κB Activation

| Parameter | Value/Range | Biological Context | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| IκBα Degradation Onset | 5-10 minutes | Macrophages stimulated with LPS [13] | Western Blot |

| NF-κB Nuclear Translocation | 15-40 minutes | TNFα-stimulated fibroblasts [15] | Immunofluorescence |

| Peak Nuclear NF-κB | 30-60 minutes | TLR-activated macrophages [13] | High-content imaging |

| NF-κB-DNA Binding Affinity | ~10-100 nM Kd | p50/RelA heterodimer to consensus κB site [14] | EMSA |

| IκBα Resynthesis | 60-120 minutes | Negative feedback loop [1] [14] | Western Blot, qPCR |

| Estimated κB Sites in Human Genome | ~300,000 | Only fraction occupied in specific contexts [14] | ChIP-seq, ENCODE |

Table 2: NF-κB Family Members and Their Roles in Canonical Signaling

| NF-κB Subunit | Precursor | Transactivation Domain | Primary Dimers in Canonical Pathway | Function in Canonical Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RelA (p65) | None | Yes | p50/RelA, p65/p65 | Primary transcriptional activator; recruits coactivators |

| p50 | p105 | No | p50/RelA, p50/p50 | DNA binding; nuclear localization |

| c-Rel | None | Yes | p50/c-Rel | Alternative transcriptional activator |

| IκBα | None | N/A | N/A | Major cytoplasmic inhibitor; negative feedback |

Research Reagent Solutions for NF-κB Translocation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NF-κB Nuclear Translocation Assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | RAW 264.7 G9 (macrophages), HeLa, HEK293, primary dermal fibroblasts | Model systems for studying NF-κB activation | RAW G9 cells stably express GFP-RelA for live imaging [13] [15] |

| Activation Stimuli | LPS (TLR4 agonist), TNFα, IL-1β | Induce canonical NF-κB pathway activation | Typical concentrations: LPS 10-100 ng/mL, TNFα 10-20 ng/mL [13] [15] |

| Nuclear Stains | Hoechst 33342, DAPI, NucBlue Live | Nuclear counterstain for imaging and normalization | Essential for defining nuclear region in image analysis [13] [15] |

| Fixation Reagents | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Preserve cellular architecture and protein localization | Freshly prepared PFA recommended for best results [13] |

| Permeabilization Agents | 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Saponin, 0.05% NP-40 | Enable antibody access to intracellular epitopes | Concentration critical for membrane integrity [15] [16] |

| NF-κB Antibodies | Anti-RelA/p65 (Santa Cruz sc-109), Anti-acetylated NF-κB (CST 3045) | Detect endogenous NF-κB for immunostaining | Validate for specific applications (WB, ICC, ChIP) [13] [15] |

| Fractionation Detergents | NP-40 (0.1-0.5%), Tween-20 | Selective membrane permeabilization for fractionation | Lower concentrations (0.1%) preserve nuclear integrity [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring NF-κB Translocation

Image-Based Measurement of NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

The following protocol describes a method for quantifying NF-κB activation through nuclear translocation in macrophages, adaptable to other adherent cell types, using either stable expression of GFP-tagged RelA or immunodetection of endogenous RelA [13] [15].

Materials Required:

- Cells: RAW 264.7 G9 macrophages stably expressing RelA-GFP or primary cells

- Culture medium appropriate for cell type

- Activation stimulus: LPS, TNFα, or other relevant activator

- Fixation: 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS

- Nuclear stain: Hoechst 33342 or DAPI

- Permeabilization buffer: PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% saponin

- Blocking solution: 5% BSA in PBS

- Primary antibody: Anti-RelA/p65 (e.g., Santa Cruz sc-109)

- Secondary antibody: Fluorescently-labeled (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488)

- Clear-bottom 96-well or 384-well plates for imaging

- High-content imaging system or fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed 10,000 cells per well in a clear-bottom black 96-well plate in 100 μL culture medium.

- Incubate overnight at 37°C, 5% CO₂ to reach 80-90% confluence.

Cell Stimulation:

- Prepare fresh dilutions of stimulus (e.g., LPS at 110 ng/mL in culture medium).

- Remove culture medium and add stimulus-containing medium.

- Incubate for appropriate time points (typically 15-60 minutes) at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Cell Fixation:

- Add 200 μL of pre-warmed 4% PFA directly to wells for a final concentration of approximately 2%.

- Incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes.

- Aspirate PFA and wash once with 500 μL PBS.

Immunostaining (for endogenous NF-κB):

- Permeabilize cells with 200 μL permeabilization buffer for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Aspirate and add blocking solution (5% BSA) for 30-60 minutes.

- Incubate with primary antibody diluted in blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3 times with PBS.

- Incubate with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Wash 3 times with PBS.

Nuclear Staining and Imaging:

- Add nuclear stain (Hoechst or DAPI) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Seal plate with clear film and proceed to imaging.

- Acquire images using 20× or 40× objective on high-content imager or fluorescence microscope.

- For GFP-RelA expressing cells, skip immunostaining steps and proceed directly to fixation and nuclear staining.

Image Analysis:

- Use image analysis software to identify nuclei based on nuclear stain.

- Define cytoplasmic ring around each nucleus.

- Measure mean fluorescence intensity of NF-κB signal (GFP or immunostain) in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments.

- Calculate nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio for each cell: N/C Ratio = Mean Nuclear Intensity / Mean Cytoplasmic Intensity.

- Analyze at least 100-200 cells per condition for statistical power.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental steps from cell preparation to data analysis:

REAP Method for Rapid Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Fractionation

The REAP (Rapid, Efficient, And Practical) method is a quick, non-ionic detergent-based technique for subcellular fractionation that minimizes protein degradation and maintains protein interactions, ideal for tracking rapid changes in NF-κB localization [16].

Materials:

- Ice-cold PBS

- 0.1% NP-40 in PBS (ice-cold)

- Tabletop centrifuge

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Laemmli sample buffer

Procedure:

- Wash cells in ice-cold PBS and scrape from culture dishes on ice.

- Collect cells in 1 mL PBS in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge for 10 seconds at maximum speed in tabletop microcentrifuge.

- Resuspend cell pellet in 900 μL ice-cold 0.1% NP-40 in PBS.

- Triturate 5 times using p1000 micropipette.

- Remove 300 μL as "whole cell lysate" and add 100 μL 4× Laemmli buffer.

- Centrifuge remaining 600 μL for 10 seconds.

- Remove 300 μL supernatant as "cytosolic fraction" and add 100 μL 4× Laemmli buffer.

- Discard remaining supernatant and wash pellet with 1 mL 0.1% NP-40 in PBS.

- Centrifuge for 10 seconds, discard supernatant.

- Resuspend pellet in 180 μL 1× Laemmli buffer as "nuclear fraction."

- Sonicate nuclear fraction and whole cell lysate twice for 5 seconds each.

- Boil all samples for 1 minute before Western blot analysis.

Western Blot Analysis:

- Use antibodies against NF-κB p65/RelA for tracking translocation.

- Verify fraction purity with markers: lamin A/C or nucleoporin for nuclear fraction; pyruvate kinase or α-tubulin for cytoplasmic fraction.

- Typical results show NF-κB predominantly in cytoplasmic fraction of unstimulated cells, shifting to nuclear fraction after stimulation.

Technical Considerations and Applications in Drug Development

The methods described for monitoring NF-κB nuclear translocation have significant applications in basic research and drug development. When implementing these protocols, several technical considerations are essential for obtaining reliable results. The choice of detection method depends on the specific research question: high-content imaging provides single-cell resolution and reveals population heterogeneity, while biochemical fractionation offers quantitative protein data suitable for subsequent analysis like Western blotting [13] [16] [14]. For screening applications, the GFP-RelA system in a multi-well format enables higher throughput [13].

In drug development, these assays are invaluable for screening therapeutic compounds that modulate NF-κB activity, particularly for inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancer [10] [11]. Many natural products and synthetic drugs with anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties have been shown to inhibit NF-κB signaling [10]. When interpreting results, researchers should consider the dynamic and oscillatory nature of NF-κB activation, which can exhibit different activation states including transient "high-ON" states in acute inflammation and persistent "low-ON" states in chronic inflammation and cancer [14]. The integration of NF-κB translocation assays with other methods such as electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and transcriptome analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of NF-κB activity from translocation to target gene regulation [13] [14].

Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) represents a family of inducible transcription factors that serve as pivotal regulators of immunity, inflammation, and cell survival. First identified in 1986 by Ranjan Sen and David Baltimore as a nuclear protein binding to the immunoglobulin κ light-chain enhancer in B cells, NF-κB has since been recognized as a master coordinator of gene expression programs in response to diverse immunological challenges [2] [17]. The NF-κB system operates through sophisticated molecular mechanisms that allow cells to mount precise transcriptional responses to environmental stimuli, including pathogens, cytokines, and cellular stress signals. When dysregulated, NF-κB signaling contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancers, making it a compelling therapeutic target for drug development [18] [10] [17].

The mammalian NF-κB transcription factor family comprises five structurally related members: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p105/p50), and NF-κB2 (p100/p52). These proteins share a conserved Rel homology domain (RHD) that mediates DNA binding, dimerization, and interaction with inhibitory proteins [2] [10]. The subunits form various homo- and heterodimers, with the p50/RelA heterodimer representing the most abundant and extensively studied combination. RelA, RelB, and c-Rel contain C-terminal transactivation domains that enable them to directly stimulate transcription, while p50 and p52 homodimers lacking these domains can function as transcriptional repressors [10] [17]. This combinatorial complexity allows NF-κB to regulate diverse gene sets with precise context-dependent specificity.

NF-κB Signaling Pathways

Cells activate NF-κB through two principal signaling routes: the canonical (or classical) and non-canonical (or alternative) pathways. These pathways differ in their activation mechanisms, kinetics, and biological functions, yet they exhibit significant crosstalk that enables integrated cellular responses [18] [12].

The Canonical NF-κB Pathway

The canonical NF-κB pathway responds to a broad range of stimuli, including ligands of cytokine receptors (e.g., TNFR, IL-1R), pattern-recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs), antigen receptors (TCR, BCR), and various stress signals [18] [2]. This pathway mediates rapid but transient NF-κB activation, typically within minutes of stimulation. In resting cells, canonical NF-κB dimers (primarily p50/RelA and p50/c-Rel) are sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins, particularly IκBα [18] [10].

Upon cell stimulation, a signaling cascade converges on the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, composed of two catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit (NEMO/IKKγ). Activation of the IKK complex, particularly through phosphorylation of IKKβ by upstream kinases such as TAK1, leads to site-specific phosphorylation of IκBα [2] [17]. Phosphorylated IκBα undergoes K48-linked polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome, liberating the NF-κB dimers [2]. The exposed nuclear localization sequences enable NF-κB nuclear translocation, DNA binding to κB enhancer elements, and transcriptional activation of target genes [2] [10].

The canonical pathway regulates the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1), adhesion molecules, and enzymes such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [18]. This pathway also stimulates the resynthesis of IκBα, creating an auto-regulatory feedback loop that terminates NF-κB activity and restores cellular homeostasis [10].

The Non-Canonical NF-κB Pathway

The non-canonical NF-κB pathway responds to a more limited set of stimuli, primarily ligands of specific TNF receptor superfamily members including BAFFR, CD40, LTβR, and RANK [18] [10]. This pathway operates with slower kinetics (hours rather than minutes) and depends on the inducible processing of the NF-κB2 precursor protein p100 into mature p52 [18].

Activation of the non-canonical pathway centers on NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), which phosphorylates and activates IKKα homodimers [2] [10]. Activated IKKα then phosphorylates p100, triggering its partial ubiquitination and proteasomal processing to p52. This processing event removes the C-terminal IκB-like domain of p100, allowing nuclear translocation of the predominant non-canonical dimer p52/RelB [18] [10]. The non-canonical pathway plays crucial roles in lymphoid organ development, B cell maturation, and adaptive immunity [2] [12].

Diagram 1: NF-κB Signaling Pathways. The canonical pathway (top) responds to diverse stimuli and activates IKK complex-mediated IκBα degradation, leading to p50/RelA nuclear translocation. The non-canonical pathway (bottom) responds to specific TNF receptor family members and involves NIK-mediated p100 processing to p52, enabling p52/RelB nuclear translocation.

NF-κB in Immune Regulation and Inflammation

NF-κB in Innate Immunity and Inflammation

NF-κB serves as a master regulator of innate immune responses, particularly in myeloid cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. These cells express pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), leading to NF-κB activation and subsequent inflammatory gene expression [18]. In macrophages, NF-κB activation through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) drives polarization toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, characterized by production of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12), chemokines, and additional inflammatory mediators [18].

The critical role of NF-κB in coordinating inflammatory responses is exemplified by its regulation of numerous genes encoding pro-inflammatory molecules. TLR4 activation by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) initiates signaling through both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways, both converging on NF-κB activation [18]. The MyD88-dependent pathway involves IRAK kinases and TRAF6, leading to TAK1 activation and subsequent IKK stimulation. The TRIF-dependent pathway activates NF-κB through RIP1, providing an alternative route to inflammation [18]. This sophisticated regulatory network ensures robust inflammatory responses to diverse microbial challenges while maintaining signaling specificity.

NF-κB in Adaptive Immunity

In adaptive immunity, NF-κB regulates multiple aspects of T cell and B cell biology. Canonical NF-κB members, particularly RelA and c-Rel, play central roles in mediating T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and naive T cell activation [18] [12]. NF-κB activation in T cells involves the CBM signalosome (composed of CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1), which recruits TRAF6 and TAK1 to activate the IKK complex [12].

NF-κB signaling influences T helper cell differentiation, particularly the development of inflammatory Th1 and Th17 subsets, and regulates T cell survival through induction of anti-apoptotic genes [18] [12]. In B cells, NF-κB activation is essential for development, survival, and antibody responses. The non-canonical pathway specifically regulates B cell maturation and lymphoid organogenesis through receptors such as BAFFR [10] [12]. Dysregulated NF-κB activation in lymphocytes contributes to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases by promoting aberrant T cell activation and inflammatory cytokine production [18].

NF-κB in Human Disease

Dysregulated NF-κB activation is a hallmark of numerous pathological conditions, including chronic inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. The pathogenic mechanisms involve constitutive NF-κB activation that perpetuates inflammatory responses, promotes cell survival, and drives pathological tissue remodeling [18] [10].

In rheumatoid arthritis, persistent NF-κB activation in synovial fibroblasts and immune cells drives production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6), matrix metalloproteinases, and adhesion molecules that collectively mediate joint destruction [2] [10]. In inflammatory bowel diseases, NF-κB activation in intestinal epithelial and immune cells disrupts mucosal barrier function and amplifies inflammatory cascades [10]. Psoriasis represents another NF-κB-driven disorder, with recent research identifying the c-Rel subunit as a critical regulator of TLR7-induced inflammation in dendritic cells that exacerbates disease pathology [19].

In cancer, NF-κB contributes to multiple aspects of tumorigenesis, including cancer cell proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, angiogenesis, metastasis, and therapy resistance [10] [17]. Constitutively active NF-κB is observed in various hematological malignancies, including Hodgkin's lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma, as well as in solid tumors [2] [10]. The transcription factor promotes tumor development through induction of anti-apoptotic genes (e.g., BCL-2, XIAP), cell cycle regulators, and pro-angiogenic factors [2].

Table 1: NF-κB in Human Disease Pathogenesis

| Disease Category | Specific Disorders | NF-κB Involvement | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Inflammatory Diseases | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Constitutive activation in synovium [2] [10] | Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6), matrix metalloproteinases [2] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Activation in epithelial and immune cells [10] | Disruption of mucosal barrier, amplification of inflammation [10] | |

| Psoriasis | c-Rel-dependent inflammation [19] | TLR7-mediated activation in dendritic cells, skin inflammation [19] | |

| Autoimmune Diseases | Multiple Sclerosis | Dysregulated activation [10] | Inflammation, demyelination [10] |

| Cancer | Hematological Malignancies | Constitutive activation [2] [10] | Promotion of cell survival, proliferation, chemoresistance [2] |

| Solid Tumors | Aberrant activation [10] [17] | Anti-apoptotic gene expression, angiogenesis, metastasis [10] | |

| Metabolic Diseases | Atherosclerosis | Chronic activation [10] | Vascular inflammation, plaque formation [10] |

Quantitative Assessment of NF-κB Activation

Accurate measurement of NF-κB activation is essential for both basic research and drug discovery. The subcellular localization of NF-κB subunits, particularly the nuclear translocation of RelA/p65, serves as a key indicator of pathway activation [3] [7] [8]. Various methodological approaches have been developed to quantify this translocation event, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Immunofluorescence microscopy combined with image analysis provides a sensitive approach for quantifying NF-κB nuclear translocation at the single-cell level. This method typically involves immunostaining for NF-κB subunits (e.g., p65) combined with nuclear counterstains (e.g., DAPI, Hoechst), followed by computational analysis to determine nuclear-to-cytoplasmic distribution [3] [7]. Automated image analysis algorithms calculate translocation metrics such as the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio or difference in intensity, enabling quantitative assessment of NF-κB activation [3]. This approach has been successfully applied in primary human macrophages, revealing LPS-induced NF-κB translocation with precise temporal resolution [7].

ImageStream cytometry combines the high-content information of microscopy with the statistical power of flow cytometry, allowing quantitative analysis of NF-κB translocation in thousands of individual cells [8]. This technology uses an algorithm that calculates a "similarity score" based on the pixel intensity correlation between NF-κB and nuclear staining, providing a robust metric for nuclear translocation that correlates well with Western blot and microscopy data [8]. This method is particularly valuable for detecting heterogeneity in NF-κB activation within cell populations and for analyzing suspension cells such as leukemic cell lines [8].

Table 2: Methods for Assessing NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunofluorescence Microscopy + Image Analysis | Quantifies nuclear vs. cytoplasmic intensity using algorithms [3] [7] | Single-cell resolution, accessible image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) [7] | Lower throughput, limited statistical power with small cell numbers [8] |

| ImageStream Cytometry | Flow cytometry with imaging capabilities; calculates similarity score [8] | High-throughput, statistical robustness, detects population heterogeneity [8] | Requires specialized instrumentation [8] |

| Western Blot of Nuclear Fractions | Detects NF-κB subunits in nuclear extracts [8] | Standard molecular biology technique | No single-cell information, masks population heterogeneity [8] |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | Measures DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts [7] | Direct assessment of functional activity | Low sensitivity, requires large cell numbers, radioactive materials [7] |

Protocol: NF-κB Translocation Assay in Human Macrophages

This protocol describes a quantitative immunofluorescence method for assessing NF-κB nuclear translocation in primary human macrophages, adapted from established methodologies [7]. The approach utilizes confocal microscopy and ImageJ software analysis, providing researchers with an accessible method for quantifying this key signaling event.

Sample Preparation and Stimulation

- Isolation and differentiation of primary human macrophages: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors by density-gradient centrifugation. Seed PBMCs on 13mm glass coverslips at 2×10ⵠcells/coverslip and allow monocytes to adhere for 1 hour. Remove non-adherent cells and culture adherent monocytes for 6 days in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum and 20 ng/mL M-CSF to generate macrophages [7].

- Cell stimulation: Stimulate macrophages with ultrapure LPS (10-100 ng/mL) or other NF-κB agonists (e.g., Pam3CSK4, TNF-α) for appropriate time periods (typically 15-60 minutes). Include unstimulated controls and specific inhibitors (e.g., polymyxin B for LPS neutralization) as experimental controls [7].

- Cell fixation: Fix cells with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes [7].

Immunofluorescence Staining

- Antibody staining: Incubate fixed cells with blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum) for 30 minutes. Apply primary antibody against RelA/p65 (e.g., rabbit polyclonal C-20 antibody, 2 μg/mL) diluted in blocking buffer and incubate overnight at 4°C. After washing, apply fluorescent secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated F(ab')₂ goat anti-rabbit IgG, 4 μg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature [7].

- Nuclear counterstaining: Counterstain nuclei with DAPI (2 μg/mL) for 5 minutes. Mount coverslips using hard-set mounting medium [7].

- Image acquisition: Acquire fluorescence images using a confocal microscope with appropriate laser lines and emission filters. Capture 5 or more high-power fields per condition, selecting fields based on DAPI staining to avoid bias. Use consistent acquisition settings (laser power, gain, offset) across all samples [7].

Image Analysis with ImageJ

- Image processing: Open images in ImageJ and split channels. Apply a median filter (3×3 pixel radius) to reduce noise. Create binary masks for nuclear (DAPI) and NF-κB staining using automatic thresholding (Isodata algorithm) [7].

- Region of interest (ROI) definition: Use the DAPI mask to define nuclear ROIs. Subtract the nuclear mask from the NF-κB mask to create cytoplasmic ROIs. Apply these ROIs to the original NF-κB images to separate nuclear and cytoplasmic signals [7].

- Quantification: Measure mean fluorescence intensity for NF-κB in nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Calculate translocation metrics: Nuclear-to-Cytoplasmic Ratio = Mean Nuclear Intensity / Mean Cytoplasmic Intensity; or Cyto-Nuc Difference = Mean Cytoplasmic Intensity - Mean Nuclear Intensity [3] [7]. Analyze at least 500 cells per condition to ensure statistical power [7].

Diagram 2: NF-κB Translocation Assay Workflow. The experimental procedure encompasses cell stimulation, fixation, immunofluorescence staining, image acquisition, and quantitative image analysis to determine NF-κB nuclear translocation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for NF-κB Translocation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Primary human monocyte-derived macrophages [7] | Physiologically relevant model for innate immunity studies |

| THP-1 human monocytic cell line [20] | Differentiable to macrophage-like state with PMA/TPA treatment | |

| NF-κB Activators | Ultrapure LPS (TLR4 ligand) [7] [20] | Canonical pathway activation via TLR4 |

| TNF-α (cytokine) [8] | Canonical pathway activation via TNFR1 | |

| CD40L, BAFF (cytokines) [18] [10] | Non-canonical pathway activation | |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-RelA/p65 (C-20) antibody [7] | Immunofluorescence detection of primary NF-κB subunit |

| Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies [7] [8] | Fluorescent detection for microscopy/imaging | |

| Nuclear Stains | DAPI, Hoechst, DRAQ5 [3] [8] | Nuclear counterstaining for segmentation |

| Inhibitors | IKK inhibitors (e.g., BMS-345541) [17] | Specific pathway inhibition for mechanistic studies |

| Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) [17] | Block IκBα degradation | |

| Natural compounds (e.g., Pinostrobin) [20] | Experimental anti-inflammatory agents |

Therapeutic Targeting of NF-κB

The central role of NF-κB in inflammation and cancer has motivated extensive drug discovery efforts targeting this pathway. Therapeutic strategies include small molecule inhibitors, biological agents, and natural compounds that interfere with specific steps in NF-κB activation [17].

IKK inhibitors represent a direct approach to suppressing NF-κB signaling by preventing IκB phosphorylation and degradation. However, the broad physiological functions of NF-κB necessitate careful consideration of therapeutic windows and potential immunosuppressive side effects [17]. Alternative strategies include proteasome inhibitors that prevent IκB degradation, nuclear translocation inhibitors that block NF-κB nuclear import, and compounds that interfere with NF-κB DNA binding [17].

Natural products with NF-κB inhibitory activity offer promising therapeutic candidates with potentially favorable safety profiles. Recent research has identified pinostrobin, a natural flavonoid, as an effective NF-κB inhibitor that blocks IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, thereby preventing NF-κB nuclear translocation and suppressing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1, CXCL10) in human macrophages [20]. Such compounds may provide templates for developing targeted anti-inflammatory therapies with reduced side effects.

Biologics targeting extracellular NF-κB activators, particularly TNF-α inhibitors, have revolutionized the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease [10] [17]. Additional approaches include receptor-blocking antibodies, antisense oligonucleotides, and gene therapy strategies designed to modulate specific NF-κB components [17]. The future of NF-κB-targeted therapy likely lies in context-specific inhibition, pathway modulation rather than complete blockade, and combination strategies that enhance efficacy while minimizing toxicity.

Nuclear Translocation as a Key Regulatory Checkpoint in NF-κB Activation

Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB) represents a family of transcription factors that function as master regulators of immune and inflammatory responses, controlling the expression of numerous genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and regulators of cell survival and proliferation [13] [1]. The NF-κB family comprises five structurally related proteins: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50), and NF-κB2 (p52), which form various transcriptionally active homo- and heterodimers [13] [1]. Among these, the RelA-p50 heterodimer is considered the prototypical NF-κB complex and has been most extensively studied [13]. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory proteins of the IκB family, which mask the nuclear localization signals of NF-κB proteins and prevent their nuclear import [13] [1]. Upon cellular activation by diverse stimuli including pathogens, cytokines, and stress signals, a well-orchestrated activation cascade is triggered, culminating in the critical regulatory checkpoint of NF-κB nuclear translocation [13] [21].

The translocation of NF-κB from the cytoplasm to the nucleus represents a decisive step in coupling extracellular stimuli to specific genomic responses, serving as a fundamental control point in the inflammatory signaling cascade [3]. This process is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms, including stimulus-dependent inhibitor degradation, post-translational modifications, and feedback control systems [13] [22]. The nuclear translocation checkpoint ensures that NF-κB-dependent gene expression occurs only when appropriate signals are received, thereby preventing aberrant inflammatory responses and maintaining cellular homeostasis. Understanding the dynamics and regulation of this process provides critical insights into both physiological immune responses and pathological conditions involving NF-κB dysregulation, including autoimmune diseases, cancer, and chronic inflammatory disorders [13] [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of NF-κB Activation and Nuclear Import

The Canonical NF-κB Signaling Pathway

The canonical NF-κB activation pathway begins with the recognition of extracellular stimuli through specific cell surface receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), cytokine receptors (e.g., TNFR, IL-1R), and antigen receptors [3] [1]. Receptor engagement triggers the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, composed of two catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit (NEMO/IKKγ) [1]. The activated IKK complex phosphorylates IκB proteins at specific N-terminal serine residues, marking them for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [13] [1]. This degradation process liberates the NF-κB dimer from its cytoplasmic sequestration, exposing its nuclear localization signal and enabling its interaction with the nuclear import machinery [1].

The translocation process is not merely a passive diffusion but an active transport mechanism involving importin proteins that recognize the exposed nuclear localization signals on NF-κB subunits [1]. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB dimers bind to specific κB DNA sequences in the regulatory regions of target genes, recruiting transcriptional co-activators or co-repressors to initiate or suppress gene expression [13]. The activation process is subject to multiple layers of regulation, including post-translational modifications of NF-κB subunits (such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination) that modulate DNA binding affinity, transcriptional activity, and nuclear retention [13] [23].

Feedback Regulation and Termination Mechanisms

The NF-κB signaling pathway incorporates sophisticated feedback mechanisms to ensure appropriate termination of the inflammatory response. One of the primary negative feedback regulators is IκBα, which is itself an NF-κB target gene [22] [1]. Newly synthesized IκBα enters the nucleus, where it binds to NF-κB dimers, displacing them from DNA and facilitating their export back to the cytoplasm through nuclear export sequences, thereby re-establishing the latent state of the pathway [3] [1]. Additional negative regulators include A20/TNFAIP3, a deubiquitinating enzyme that inhibits IKK activation, and various other proteins that interfere at different steps of the signaling cascade [22].

The dynamic balance between positive and negative regulators results in complex temporal patterns of NF-κB nuclear localization, which can exhibit monophasic, oscillatory, or sustained activation profiles depending on cell type, stimulus, and cellular context [22]. In macrophages activated through TLR pathways, NF-κB typically translocates to the nucleus within 20-40 minutes after stimulation, showing nuclear persistence rather than oscillations, which contrasts with the oscillatory behavior observed in fibroblasts in response to TNF-α [13] [22]. These cell-type-specific dynamics contribute to the precise control of gene expression programs appropriate for specific physiological contexts.

Methodological Approaches for Studying NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

Multiple experimental techniques have been developed to monitor and quantify NF-κB activation, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and applications [13]. These methods target different stages of the NF-κB activation cascade, from initial IκB degradation to final transcriptional activation, providing complementary insights into the regulation and dynamics of this critical signaling pathway.

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Assessing NF-κB Activation

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameter | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Translocation Assays | Fluorescence microscopy (live-cell or fixed) [13] [21] | Subcellular localization (cytoplasm to nucleus) | Single-cell resolution, spatial information, kinetic analysis | Requires specialized equipment, image analysis expertise |

| Cell fractionation + Western blot [13] | NF-κB protein in nuclear vs. cytoplasmic fractions | Population average, standard laboratory technique | No single-cell resolution, potential cross-contamination | |

| DNA Binding assays | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) [13] | Protein-DNA binding in vitro | Direct measure of DNA binding activity | Radioactive labels, semi-quantitative, technically challenging |

| No-Shift assay (ELISA format) [13] | Protein-DNA binding in vitro | Quantitative, higher throughput | May not reflect cellular context | |

| Transcriptional Activity | Reporter gene assays (luciferase) [13] | Promoter-driven reporter expression | Functional readout of transcriptional activity | Transfection artifacts, artificial promoter context |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) [13] | Endogenous DNA binding in vivo | Genome-wide mapping (ChIP-seq), endogenous context | Technically demanding, population average | |

| Post-translational Modifications | Western blot with phospho-specific antibodies [13] | Phosphorylation, acetylation status | Information on regulatory modifications | Population average, may not correlate with functional activity |

Image-Based Translocation Assays: Principles and Quantification

Image-based assays for NF-κB nuclear translocation have emerged as particularly powerful approaches due to their ability to provide single-cell resolution, spatial information, and dynamic kinetic data [13] [3]. These techniques typically utilize either stable expression of fluorescent protein-tagged NF-κB subunits (e.g., GFP-RelA) or immunocytochemical detection of endogenous NF-κB proteins combined with fluorescent dyes for nuclear counterstaining (e.g., Hoechst 33342, DAPI) [13] [21].

The quantitative analysis of NF-κB translocation relies on computational algorithms that define nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments based on the nuclear stain, then measure the intensity and distribution of the NF-κB signal within these defined regions [3]. Common quantitative parameters include:

- Nuclear-to-Cytoplasmic Ratio (Nuc/Cyt Ratio): The ratio of average NF-κB intensity in the nuclear region to the average intensity in the cytoplasmic region [3].

- Cytoplasmic-to-Nuclear Difference (Cyto-Nuc Difference): The absolute difference in NF-κB intensity between cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments [3].

- Pearson's Correlation Coefficient: A measure of pixel intensity correlation between the NF-κB signal and nuclear stain, with values ≥0.6 typically indicating positive translocation [21].

- Percent Translocation-Positive Cells: The percentage of cells in a population exhibiting translocation above a defined threshold [21].

Advanced high-content screening platforms and automated image analysis have enabled the application of these assays to drug discovery and chemical genomics, allowing for the identification of novel modulators of NF-κB signaling [3] [24]. Furthermore, technological improvements such as image deconvolution algorithms have significantly enhanced the accuracy and statistical power of translocation measurements by reducing out-of-focus light artifacts that can lead to false positives or negatives in standard widefield microscopy [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Live-Cell Imaging of NF-κB Translocation Using GFP-RelA

This protocol describes a method for monitoring NF-κB nuclear translocation dynamics in live macrophages expressing a GFP-tagged RelA fusion protein, enabling real-time kinetic analysis of pathway activation in response to inflammatory stimuli [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Raw 264.7 G9 cells stably expressing RelA-GFP [13]

- Culture medium: DMEM containing 10% FCS, 20 mM HEPES buffer, 4 mM L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin [13]

- Non-treated tissue culture flasks [13]

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- 2 mM EDTA in PBS

- TLR ligands: Ultrapure LPS (1 mg/ml stock) [13]

- Clear bottom, black-walled 96-well or 384-well microplates [13]

- Nuclear stain: Hoechst 33342 or similar cell-permeable DNA dye

- Live-cell imaging system with environmental control (temperature, COâ‚‚)

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Preparation:

- Grow RAW264.7 G9 cells in culture medium in non-treated tissue culture flasks at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂.

- Allow cells to reach 80-90% confluence prior to experimentation.

Cell Seeding:

- Aspirate medium and detach cells by adding cold 2 mM EDTA in PBS for 5 minutes.

- Gently pipette up and down at least 5 times to generate a single-cell suspension.

- Collect cells in a centrifuge tube and add an equivalent volume of culture medium.

- Centrifuge for 5 minutes at 400 × g.

- Resuspend pellet in fresh growth medium and count cells.

- Seed 10,000 cells per well in black, clear-bottom 96-well plates in a total volume of 100 μl.

- Incubate overnight to allow cell attachment and recovery.

Stimulus Preparation and Treatment:

- The following day, prepare working dilutions of TLR ligands in culture medium.

- For LPS stimulation, dilute stock solution (1 mg/ml) to 110 ng/ml in culture medium.

- Replace medium in experimental wells with ligand-containing medium.

Live-Cell Imaging:

- Place microplate in pre-warmed live-cell imaging system maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Define imaging parameters: acquire images using 20× or 40× objective at multiple sites per well.

- Set appropriate exposure times for GFP and nuclear stain channels.

- Establish imaging time course with frequent intervals (e.g., every 5-10 minutes) for several hours to capture translocation dynamics.

Image Analysis:

- Use translocation analysis module in image analysis software.

- Identify nuclei based on Hoechst staining and create nuclear masks.

- Define cytoplasmic region as a ring around the nuclear mask.

- Measure GFP-RelA intensity in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments for each cell.

- Calculate translocation parameters (Nuc/Cyt ratio, Cyto-Nuc difference) for each time point.

- Export data for statistical analysis and visualization.

Protocol 2: Fixed-Cell Immunofluorescence Detection of Endogenous NF-κB

This protocol describes the detection and quantification of endogenous NF-κB nuclear translocation using immunostaining in fixed cells, applicable to various cell types including primary macrophages and HeLa cells [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- HeLa cells or primary macrophages

- Appropriate cell culture medium and supplements

- 96-well black wall, clear bottom microplates

- Fixative: 4% formaldehyde in PBS

- Blocking/permeabilization buffer: PBS + 5% donkey serum + 0.2% Triton X-100 [21]

- Antibody dilution buffer: PBS + 1% donkey serum + 0.02% Triton X-100 [21]

- Stimuli: TNF-α (1500 ng/ml), IL-1α, or other NF-κB inducers

- Primary antibody: Anti-NF-κB RelA/p65 (e.g., ProteinTech cat. #10745-1-AP) [21]

- Secondary antibody: Fluorescently-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488)

- Nuclear counterstain: Hoechst 33342, DAPI, or DRAQ5

- Optional: Phalloidin conjugate for actin staining

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Stimulation:

- Plate cells into black-wall, clear bottom 96-well plates at appropriate density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for HeLa cells).

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 24 hours to allow cell attachment and growth.

- Treat cells with NF-κB stimuli (e.g., TNF-α at 1500 ng/ml) for appropriate time points (0, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes).

- Include unstimulated controls and inhibitor treatments as experimental design requires.

Cell Fixation and Permeabilization:

- After stimulation, wash cells twice with PBS.

- Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash cells three times with PBS.

- Incubate with blocking/permeabilization buffer for 60 minutes.

Immunostaining:

- Incubate cells with primary antibody (anti-RelA, 1:200 dilution) in antibody dilution buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash cells three times with PBS.

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody (1:500 dilution) in antibody dilution buffer for 2 hours at room temperature.

- During the last 30 minutes of secondary antibody incubation, add nuclear stain (Hoechst 33342 at 1 μL/mL).

- Wash cells three times with PBS prior to imaging.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire images using high-content imaging system or fluorescence microscope.

- For improved resolution, use image deconvolution if available [21].

- Acquire multiple fields per well to ensure adequate cell numbers for statistical analysis.

- Analyze images using translocation analysis algorithm as described in Protocol 1.

- Calculate percentage of translocation-positive cells based on Pearson's correlation coefficient (threshold ≥0.6) or Nuc/Cyt ratio.

Quantitative Data and Kinetic Parameters

Temporal Dynamics of NF-κB Nuclear Translocation

The kinetics of NF-κB nuclear translocation vary significantly depending on cell type, stimulus, and specific experimental conditions. Understanding these temporal dynamics is essential for proper experimental design and interpretation of results.

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters of NF-κB Nuclear Translocation in Different Cell Models

| Cell Type | Stimulus | Time to Initial Detection | Peak Translocation | Translocation Half-time | Duration | Dynamic Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAW264.7 Macrophages [13] | LPS (TLR4) | 10-15 min | 30-45 min | ~20 min | 1-3 hours | Monophasic, sustained |

| HeLa Cells [21] | TNF-α (1500 ng/ml) | 5-10 min | 30-45 min | 7-8 min [24] | 45-60 min | Transient, returns to baseline by 60 min |

| Human Chondrocytes [24] | TNF-α or IL-1 | 10-15 min | 30-45 min | 12-13 min [24] | 1-2 hours | Monophasic |

| A549 Epithelial Cells [22] | TNF-α (30 ng/ml) | 10-20 min | 30-60 min | ~15 min | Variable | Monophasic or damped oscillations |

Quantification Metrics and Statistical Analysis

The quantitative analysis of NF-κB translocation generates multiple parameters that can be used to compare experimental conditions and assess statistical significance. Different calculation methods offer complementary information about the translocation process.

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters for NF-κB Nuclear Translocation Analysis

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Typical Baseline Values (Unstimulated) | Typical Activated Values | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear-to-Cytoplasmic Ratio | Mean nuclear intensity / Mean cytoplasmic intensity | 0.5 - 0.8 | 1.5 - 3.0 | Standard measure of translocation extent |

| Cyto-Nuc Difference | Mean cytoplasmic intensity - Mean nuclear intensity | Positive values | Negative values | Alternative metric for translocation |

| Percent Positive Cells | % cells with Nuc/Cyt ratio > threshold (e.g., 1.2) | 5-15% | 60-90% | Population response assessment |

| Pearson's Correlation Coefficient | Pixel intensity correlation between NF-κB and nuclear stain | <0.3 | ≥0.6 [21] | Objectively defined translocation events |

| Total Nuclear Intensity | Integrated intensity of NF-κB in nucleus | Low | High | Measure of nuclear accumulation |

| Translocation Rate | Slope of Nuc/Cyt ratio over time | Near zero | Peak 0.1-0.3 minâ»Â¹ | Kinetic analysis of activation speed |

Advanced imaging and analysis techniques such as image deconvolution have been shown to significantly improve the statistical quality of translocation data. Studies comparing standard widefield microscopy with deconvolution approaches demonstrate that the latter reduces standard deviations between replicates by 30-50%, thereby increasing statistical power and assay robustness [21]. This improvement is particularly important for detecting subtle phenotypic changes in screening applications or when comparing the efficacy of pharmacological inhibitors.

Successful investigation of NF-κB nuclear translocation requires careful selection of appropriate biological tools, detection reagents, and experimental conditions. The following table summarizes key resources for implementing the described methodologies.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for NF-κB Translocation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | RAW264.7 G9 (GFP-RelA) [13] | Stably expresses GFP-RelA fusion protein | Enables live-cell imaging without staining |

| HeLa cells [21] | Commonly used model for translocation studies | Well-characterized NF-κB response to TNF-α | |

| Primary macrophages [13] | Physiologically relevant innate immune cells | Requires isolation, more variable response | |

| Activation Stimuli | Ultrapure LPS [13] | TLR4 agonist for macrophage activation | Concentration range: 10-100 ng/ml |

| TNF-α [21] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Potent NF-κB inducer in most cell types | |

| IL-1α/IL-1β [3] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Alternative stimulus for NF-κB pathway | |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-RelA/p65 antibodies [21] | Detection of endogenous NF-κB | Multiple commercial sources available |

| Fluorescent secondary antibodies | Signal amplification and detection | Match to microscope filter sets | |

| Hoechst 33342, DAPI [13] [21] | Nuclear counterstain | Cell-permeable (Hoechst) or fixed-cell (DAPI) | |

| Inhibitors/Controls | IKK inhibitors (e.g., BAY-11) | Negative control for inhibition | Confirm specificity of translocation |

| Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) [24] | Blocks IκB degradation | Prevent NF-κB activation | |

| Kinase inhibitors (e.g., K252a) [24] | Broad-spectrum kinase inhibition | IC₅₀ ~0.4 μM for NF-κB inhibition | |

| Instrumentation | High-content imaging systems [3] | Automated image acquisition and analysis | Essential for screening applications |

| Image deconvolution software [21] | Enhanced image resolution | Improves assay accuracy and statistical power |

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Methodological Challenges and Solutions

The accurate measurement of NF-κB nuclear translocation presents several technical challenges that require careful experimental design and appropriate controls. A common issue in image-based assays is the potential for out-of-focus light in widefield microscopy, which can lead to inaccurate quantification of nuclear localization [21]. This problem is particularly pronounced in thicker cells or when using high magnification objectives. Implementation of image deconvolution algorithms can significantly mitigate this issue by computationally removing out-of-focus light, resulting in improved image resolution and more accurate translocation measurements [21]. Comparative studies have demonstrated that deconvolution approaches reduce false-positive and false-negative translocation calls and decrease variability between replicates, thereby enhancing statistical significance [21].

Another significant consideration is the substantial cell-to-cell variability in NF-κB translocation dynamics, even within clonal cell populations [22]. This heterogeneity arises from multiple sources, including differences in cellular geometry, initial concentrations of signaling components, variable IκBα translation rates, and stochastic biochemical events [22]. To address this variability, researchers should ensure adequate sample sizes (typically hundreds of cells per condition) and utilize single-cell analytical approaches rather than relying solely on population averages. Bayesian inference methods incorporating quantitative measurements of cellular geometry and NF-κB concentration have been successfully employed to estimate biophysically realistic parameters and understand the sources of cell-to-cell heterogeneity [22].

Validation and Quality Control

Rigorous validation of NF-κB translocation assays is essential for generating reliable and reproducible data. Key validation steps include:

- Time Course Experiments: Preliminary time course studies should be performed for each new cell type or stimulus to establish optimal measurement time points that capture the peak and dynamics of NF-κB translocation [21].

- Inhibitor Controls: Specific pathway inhibitors (e.g., IKK inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors) should be used to confirm that observed nuclear translocation is dependent on canonical NF-κB activation mechanisms [24].

- Antibody Validation: For immunodetection approaches, antibodies should be validated using appropriate controls including knockout cells, competing peptides, or comparison with alternative detection methods.

- Threshold Determination: Objective thresholds for defining translocation-positive cells should be established based on unstimulated control populations rather than arbitrary values [3].

- Cell Health Assessment: Concurrent assessment of cell viability and morphology should be included to exclude potential confounding effects of cytotoxicity or stress responses.

Statistical quality metrics such as Z'-factor calculations are recommended for assay validation, particularly in screening applications. For NF-κB translocation assays, Z'-factors >0.5 are typically achievable, indicating robust assays suitable for compound screening [3]. Additionally, the use of internal controls on each experimental plate (e.g., unstimulated and fully stimulated wells) facilitates normalization and comparison across multiple experiments.

NF-κB nuclear translocation represents a critical regulatory checkpoint in the inflammatory signaling cascade, serving as a decisive control point that connects extracellular stimuli to specific genomic responses. The methodologies described in this application note, particularly image-based approaches with single-cell resolution, provide powerful tools for investigating this fundamental biological process with high temporal and spatial precision. The quantitative parameters and kinetic data presented here establish benchmarks for experimental design and interpretation across different cellular models and stimulation conditions.

The continued refinement of these methodologies, including advances in live-cell imaging, image analysis algorithms, and deconvolution techniques, promises to further enhance our understanding of NF-κB biology and its regulation. These technical advances, combined with appropriate validation and quality control measures, ensure that NF-κB translocation assays remain invaluable tools for both basic research and drug discovery applications aimed at modulating inflammatory responses in health and disease.

Within the intricate landscape of the eukaryotic cell, the compartmentalization of function between the nucleus and cytoplasm is a fundamental biological principle. The nucleus serves as the command center, housing the genetic material and coordinating vital processes such as DNA replication, RNA synthesis, and gene regulation. The physical separation of the nucleus from the cytoplasm allows for sophisticated control of cellular activities, enabling precise spatial and temporal regulation of signaling events. Isolating nuclear fractions is therefore a critical methodological approach in molecular cell biology, providing a powerful means to study nuclear-specific processes, transcription factor dynamics, and gene regulatory mechanisms free from the obscuring background of the total cellular proteome. This application note details the rationale and protocols for nuclear fractionation, with a specific focus on its indispensable role in investigating the activation dynamics of the Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor, a key regulator of immune and inflammatory responses [13] [7].

The NF-κB pathway exemplifies why nuclear fractionation is a cornerstone of cellular research. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive complex bound to inhibitory proteins known as IκBs [1]. Upon receiving an activating signal—such as from pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNFα or bacterial components like LPS—a conserved signaling cascade is triggered. This leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, unmasking NF-κB's nuclear localization signal (NLS) and allowing its rapid translocation into the nucleus [3] [1]. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB binds to specific κB DNA sequences and initiates the transcription of target genes involved in inflammation, cell survival, and proliferation [13]. Consequently, the translocation of NF-κB from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is a critical, defining step in its activation, and isolating a pure nuclear fraction is essential for accurately measuring this event and understanding the resulting gene expression programs.

The Biological Imperative for Nuclear Isolation

The Nucleus as a Distinct Cellular Compartment

The nucleus is delineated from the cytoplasm by a double-membrane nuclear envelope, which is perforated by nuclear pore complexes that regulate the exchange of macromolecules. This structural segregation means that the nuclear compartment possesses a unique protein and nucleic acid composition distinct from the cytosol or other organelles. Key nuclear components include:

- Chromatin: The complex of DNA and histone proteins.

- Nucleoli: Sites of ribosomal RNA synthesis and assembly.

- The Nuclear Matrix: A proteinaceous scaffold that provides structural organization.

- Transcription Factors and Regulatory Complexes: Proteins that control gene expression.

Analyzing these components in isolation allows researchers to obtain a clear picture of nuclear events without interference from the abundant cytoplasmic proteins, which can constitute over 50% of the total cellular protein content. This is particularly crucial for studying processes like gene activation, where a transcription factor's presence and binding activity within the nucleus is the functionally relevant metric, not its total cellular abundance [7].