Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Chronic Disease: A Comparative Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of oxidative stress biomarkers across major chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Chronic Disease: A Comparative Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of oxidative stress biomarkers across major chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and neurodegenerative disorders. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the pathophysiological roles of these biomarkers, compares their clinical validity and disease-specific expressions, and evaluates advanced methodological approaches for their measurement. The content further addresses key challenges in biomarker validation and interpretation, offering insights into integrated assessment strategies and future directions for leveraging oxidative stress markers in diagnostics, prognostics, and therapeutic development.

Understanding Oxidative Stress: Core Biomarkers and Their Pathophysiological Roles in Chronic Diseases

{Introduction}

Oxidative stress is defined as a physiological state where the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelms the body's antioxidant defense capacities [1] [2] [3]. This imbalance leads to oxidative damage of vital cellular structures—lipids, proteins, and DNA—and is a recognized contributor to a wide spectrum of chronic diseases [1] [4] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the accurate assessment of oxidative stress through specific, measurable biomarkers is crucial for understanding disease pathogenesis, monitoring activity, and evaluating novel therapeutic interventions. This guide provides a comparative overview of key oxidative stress markers and the experimental protocols used to measure them in chronic disease research.

{Comparative Biomarker Profiles Across Chronic Diseases}

The following tables summarize the alterations in key oxidative stress biomarkers as observed in recent clinical studies across different pathological conditions. This comparative analysis highlights both common and disease-specific oxidative signatures.

Table 1: Markers of Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Capacity in Chronic Diseases

| Biomarker | Long COVID [5] | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [6] | Hypertension & Diabetes [4] | Medication Overuse Headache (MOH) [7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) | - | ↑ in active vs. inactive IBD and HC | ↑ (Predicts endothelial dysfunction) | - |

| DNA Damage (8-OHdG) | - | - | ↑ (Surrogate for diabetic nephropathy) | - |

| Antioxidant Enzymes (SOD, GPx) | - | ↓ in active IBD vs. HC | ↓ (Associated with β-cell failure) | - |

| Total Antioxidant Capacity (BAP/TAC) | BAP ↓ with age/BMI; Inverse correlation with CRP/ferritin | TAC ↓ in active CD vs. inactive CD | - | - |

| Composite Ratios (MHR, NHR, LHR) | - | - | - | ↑ in MOH vs. Healthy Controls |

Table 2: Clinically Accessible Composite Markers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress These ratios, derived from routine blood tests, serve as proxies for systemic oxidative stress and inflammation [7].

| Marker | Formula | Association with Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Monocyte to HDL Ratio (MHR) | Monocyte count (/µL) / HDL-C (mg/dL) | Independently associated with Medication Overuse Headache (OR = 2.32) [7] |

| Neutrophil to HDL Ratio (NHR) | Neutrophil count (/µL) / HDL-C (mg/dL) | Independently associated with Medication Overuse Headache (OR = 2.09) [7] |

| Lymphocyte to HDL Ratio (LHR) | Lymphocyte count (/µL) / HDL-C (mg/dL) | Independently associated with Medication Overuse Headache (OR = 2.56) [7] |

| Oxidative Stress Index (OSI) | (d-ROMs / BAP) × C | OSI > 1.92 identifies brain fog in Long COVID [5] |

{Experimental Protocols for Key Oxidative Stress Assays}

Standardized methodologies are essential for generating reliable and comparable data on oxidative stress. Below are detailed protocols for several cornerstone techniques in the field.

1. Diacron-Reactive Oxygen Metabolites (d-ROMs) Test

- Principle: This assay measures hydroperoxides (ROOH) in the serum, which react via a Fenton-like reaction to generate radicals that oxidize an alkyl-substituted aromatic amine substrate, producing a pink chromogen [5].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Collect venous blood and allow it to clot. Centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain clear serum.

- Reagent Preparation: Reconstitute the provided chromogen substrate (N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine) in the appropriate buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Diacron International) [5].

- Reaction: Mix 10 µL of serum sample with 1 mL of the reconstituted reagent in a cuvette.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 37°C for exactly 1 minute.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the solution photometrically at 505 nm using a spectrophotometer (e.g., on an AU480 automated analyzer) [5].

- Calculation: The d-ROMs concentration is directly proportional to the absorbance and is expressed in Carratelli Units (CARR U), where 1 CARR U corresponds to 0.08 mg of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚/dL [5].

2. Biological Antioxidant Potential (BAP) Test

- Principle: The BAP test quantifies the collective ability of serum antioxidants to reduce ferric ions (Fe³âº) to ferrous ions (Fe²âº). The ferrous ions then react with a thiocyanate derivative to produce a colored complex, the decolorization of which is inversely proportional to the serum's antioxidant power [5].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Use the same serum sample as for the d-ROMs test.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a colored solution containing ferric chloride and a thiocyanate derivative.

- Reaction: Add 10 µL of serum to 1 mL of the colored reagent and mix thoroughly.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance at 505 nm. A higher final absorbance indicates a lower reduction of Fe³⺠and thus a lower antioxidant potential.

- Calculation: The BAP value is calculated based on the decrease in absorbance relative to a blank and is expressed in µmol/L [5].

3. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation via Malondialdehyde (MDA)

- Principle: MDA, a secondary product of lipid peroxidation, reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form a pink fluorescent adduct, the Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) [4] [8].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue or dilute plasma/serum in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Reaction: Add TBA reagent and acetic acid to the sample in a test tube.

- Heating: Heat the mixture at 95°C for 60 minutes.

- Cooling & Extraction: Cool the tubes on ice and add n-butanol. Vortex and centrifuge to separate the organic (pink) layer.

- Measurement: Measure the fluorescence of the organic layer (Excitation: 515-535 nm, Emission: 553-555 nm) or its absorbance at 532-535 nm.

- Calculation: Quantify MDA concentration using a standard curve prepared from 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane [8].

4. Quantification of DNA Damage via 8-Hydroxy-2'-Deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)

- Principle: 8-OHdG is a major product of oxidative DNA damage. After DNA extraction and enzymatic hydrolysis, it can be measured with high sensitivity using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD) or mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) [4] [8].

- Detailed Protocol (HPLC-ECD):

- DNA Isolation: Isolate DNA from whole blood or tissue samples using a commercial kit with precautions to avoid artifactual oxidation (e.g., using chelating agents).

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest the purified DNA (e.g., 50-100 µg) to deoxynucleosides using a mixture of nuclease P1, phosphodiesterase I, and alkaline phosphatase.

- Chromatography: Inject the digest into an HPLC system equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column.

- Detection: Use an electrochemical detector for specific detection of 8-OHdG and a UV detector for simultaneous detection of unmodified deoxyguanosine (dG).

- Calculation: The level of oxidative damage is expressed as the ratio of 8-OHdG per 10ⵠor 10ⶠdG [4] [8].

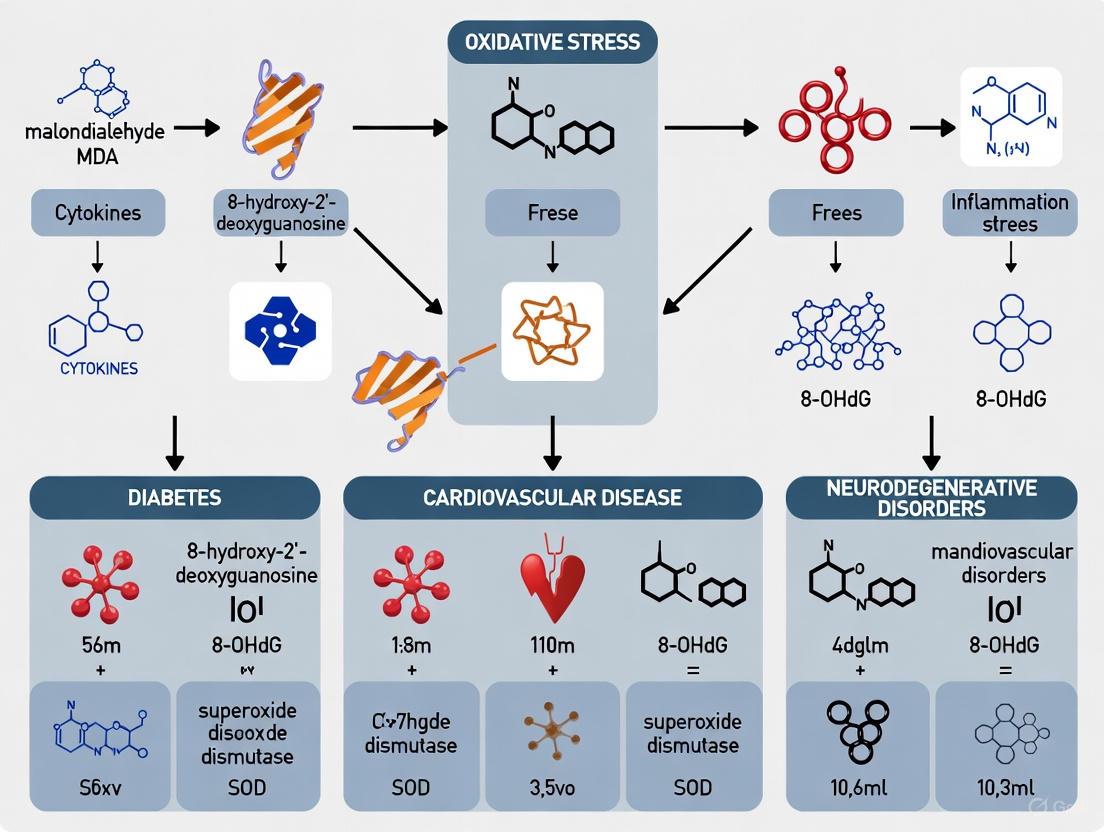

{Visualizing the Oxidative Stress Pathway and Experimental Workflow}

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of oxidative stress and a generalized experimental workflow for its assessment.

Diagram 1: The Oxidative Stress Equilibrium. This diagram illustrates the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses. An imbalance favoring ROS leads to oxidative stress and cellular damage [1] [2] [3].

Diagram 2: Oxidative Stress Assessment Workflow. A generalized flowchart for evaluating oxidative stress status through multiple complementary assays on biological samples [5] [4] [8].

{The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions}

A successful oxidative stress study relies on specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential items for setting up core experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Oxidative Stress Analysis

| Research Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| d-ROMs & BAP Test Kits (Diacron International) | Integrated system for measuring serum hydroperoxide levels (oxidant load) and total antioxidant capacity on automated clinical chemistry analyzers. | Used to establish oxidative stress index (OSI) cut-off values for identifying brain fog in Long COVID patients [5]. |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | Key reagent for the TBARS assay; reacts with malondialdehyde (MDA) to form a quantifiable pink chromogen, measuring lipid peroxidation. | Employed in clinical trials to demonstrate that almond supplementation (>60 g/day) significantly reduces plasma MDA levels [9]. |

| 8-OHdG ELISA Kits | Immunoassay-based kits for high-throughput quantification of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in urine or serum, a marker of oxidative DNA damage. | Used to show that almond consumption significantly reduces urinary 8-OHdG excretion [9]. |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay Kits | Colorimetric or fluorometric kits to measure the activity of SOD, a key enzymatic antioxidant that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radical. | Meta-analyses show reduced SOD activity in active inflammatory bowel disease compared to healthy controls [6]. |

| F2-Isoprostane Standards (for GC-MS/LC-MS) | Authentic chemical standards of F2-isoprostanes, gold-standard biomarkers for in vivo lipid peroxidation, used for accurate quantification via mass spectrometry. | Considered a validated biomarker correlating with disease progression in hypertension and diabetes research [4] [8]. |

{Conclusion}

The comparative data and methodologies outlined herein underscore that while oxidative stress is a common thread in chronic diseases, its specific biomarker profile can vary significantly. The choice of biomarkers—from gold-standard specific molecules like F2-isoprostanes to accessible composite ratios like MHR—must be aligned with the research question and clinical context. A multi-parametric approach, integrating measures of oxidant load, antioxidant capacity, and resultant biomolecular damage, provides the most comprehensive assessment. For drug development, these biomarkers offer valuable endpoints for evaluating the efficacy of novel antioxidant or redox-modulating therapies, paving the way for more targeted and effective interventions in conditions driven by oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body's antioxidant defenses, is a common pathophysiological mechanism in numerous chronic diseases [4] [10]. This imbalance leads to molecular damage through oxidation of crucial biomolecules: lipids, proteins, and DNA [11]. The resulting oxidative modifications serve as valuable biomarkers, providing measurable indicators of oxidative stress intensity, cellular damage, and disease progression [10]. These biomarkers have gained significant importance in research and clinical settings for diagnosing disease severity, monitoring progression, and evaluating therapeutic efficacy across diverse conditions including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and cancer [4] [12] [13]. The reliable detection of these oxidized molecules offers a window into the oxidative microenvironment within tissues and cells, enabling researchers and clinicians to assess the oxidative burden in patients and model systems [14] [11].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the three major biomarker classes—lipid peroxidation products, protein modifications, and DNA oxidation markers—focusing on their mechanisms, measurement methodologies, disease associations, and research applications. We present experimental data and technical protocols to facilitate informed biomarker selection for chronic disease research and drug development.

Lipid Peroxidation Products

Formation Mechanisms and Key Biomarkers

Lipid peroxidation is a chain reaction wherein ROS attack polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes and lipoproteins [14] [11]. This process proceeds through three distinct mechanisms: free radical-mediated oxidation, free radical-independent non-enzymatic oxidation, and enzymatic oxidation [14]. The primary products of lipid peroxidation are lipid hydroperoxides, which are unstable and undergo further reactions to form a variety of secondary products with diverse biological activities [14].

Key biomarkers include:

- Isoprostanes (IsoPs): Prostaglandin-like compounds formed in situ from arachidonic acid via non-enzymatic, free radical-catalyzed peroxidation. F2-isoprostanes are considered a "gold standard" for assessing oxidative stress in vivo [14] [4]. They are esterified in phospholipids and released into circulation by phospholipases.

- Neuroprostanes (NPs): Similar to IsoPs but derived from docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is highly enriched in neuronal membranes. They are particularly relevant for neurodegenerative diseases [14] [12].

- Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODEs): Oxidation products of linoleic acid, the most abundant PUFA in vivo. The ratio of cis,trans-HODE to trans,trans-HODE can indicate the efficacy of radical-scavenging antioxidants [14].

- Malondialdehyde (MDA): A reactive dialdehyde end-product of lipid peroxidation, commonly measured via the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) assay [4] [13].

- 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE): A highly reactive aldehyde that forms protein adducts, impacting signal transduction and cell function [12] [11].

- Oxysterols: Cholesterol oxidation products such as 7-ketocholesterol and 7-hydroxycholesterol, formed by enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms [14].

Experimental Detection and Analysis

Accurate measurement of lipid peroxidation biomarkers requires sophisticated analytical techniques due to their low concentrations, instability, and complex isomeric profiles.

Standard Protocols:

- Sample Preparation: Biological samples (plasma, tissues, urine) are typically processed with reduction (e.g., sodium borohydride or triphenylphosphine) to convert hydroperoxides to stable hydroxides, followed by saponification to hydrolyze esterified lipids [14].

- Extraction: Liquid-liquid extraction with organic solvents (e.g., chloroform/methanol) is commonly used to isolate lipids from biological matrices.

- Analysis:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Considered the reference method for F2-isoprostanes and HODEs due to high sensitivity and specificity [14] [15].

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Increasingly used for simultaneous quantification of multiple lipid peroxidation products (e.g., isoprostanoids, HODEs, oxysterols) without derivatization [14] [15].

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): Available for F2-isoprostanes and 4-HNE, offering high-throughput capability though potentially lower specificity than MS methods [14].

Disease Associations and Research Applications

Lipid peroxidation biomarkers show significant elevations across multiple chronic diseases, reflecting their role in pathogenesis.

Table 1: Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Chronic Diseases

| Biomarker | Cardiovascular Diseases | Neurodegenerative Diseases | Diabetes/Metabolic Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| F2-IsoPs | Significantly elevated in heart failure (ROM=2.83 vs controls) [13]; Associated with endothelial dysfunction in hypertension [4] | Increased in Alzheimer's disease (AD) plasma and CSF; Correlates with β-amyloid pathology in MCI [12] [15] | Elevated in diabetic patients; Correlates with glycemic control and complications [4] |

| MDA | Elevated in heart failure (ROM=1.87) [13]; Predicts endothelial dysfunction in hypertension [4] | Increased in AD brain and MCI patients [12] | Higher in diabetic patients with complications; Associated with insulin resistance [4] |

| HODEs | Proposed for evaluating antioxidant therapy efficacy in atherosclerosis [14] | Altered profiles in AD and MCI [14] | Used to assess oxidative burden in metabolic syndrome [14] |

| 4-HNE | Protein adducts formed in atherosclerotic plaques; Contributes to endothelial dysfunction [11] [10] | Increased protein adducts in AD brain; Linked to synaptic dysfunction [12] | Adducts formed in pancreatic β-cells under hyperglycemia [4] |

| Oxysterols | Accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques; Promote foam cell formation [14] [10] | Elevated in AD brain; Contribute to neuronal toxicity [14] | Associated with hypercholesterolemia in diabetes [14] |

Protein Oxidation Modifications

Formation Mechanisms and Key Biomarkers

Proteins are major targets for oxidative damage due to their abundance and rapid reaction rates with oxidants [16]. Oxidative protein modifications can occur directly by ROS or indirectly through reaction with lipid peroxidation products (e.g., 4-HNE, acrolein) or carbohydrate derivatives (advanced glycation end products) [12] [16].

Key biomarkers include:

- Protein Carbonyls: Formed by direct oxidation of amino acid side chains (Lys, Arg, Pro, Thr), peptide backbone cleavage, or binding of lipid peroxidation products [12] [16]. They represent a stable, broad marker of protein oxidation.

- 3-Nitrotyrosine (3-NT): Generated by tyrosine nitration mediated by peroxynitrite (ONOOâ»), a reaction product of nitric oxide and superoxide [12] [10]. It indicates nitrosative stress and altered protein signaling.

- Protein-Bound 4-HNE and Acrolein: Michael adducts formed with cysteine, lysine, or histidine residues, leading to protein dysfunction and aggregation [12].

- Advanced Oxidation Protein Products (AOPP): Dityrosine-containing cross-linked protein products formed mainly by myeloperoxidase activity [10].

- Methionine Sulfoxide: Oxidation of methionine residues to methionine sulfoxide, which can be reversed by methionine sulfoxide reductases [16].

Experimental Detection and Analysis

Protein oxidation biomarkers require specific detection methods due to their diverse chemical nature and occurrence in complex biological matrices.

Standard Protocols:

- Protein Carbonyl Detection:

- Derivatization with 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH): Sample proteins are reacted with DNPH to form hydrazone products, which can be detected spectrophotometrically (absorbance at 370-375 nm) or immunochemically using anti-DNP antibodies (Western blot or ELISA) [4] [12].

- Redox Proteomics: Protein separation by 2D-gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting with anti-DNP antibodies or direct detection using LC-MS/MS [12] [16].

- 3-Nitrotyrosine Detection:

- 4-HNE-Adduct Detection:

Disease Associations and Research Applications

Oxidative protein modifications contribute to disease pathogenesis by impairing enzyme function, disrupting cellular signaling, and promoting protein aggregation.

Table 2: Protein Oxidation Biomarkers in Chronic Diseases

| Biomarker | Cardiovascular Diseases | Neurodegenerative Diseases | Diabetes/Metabolic Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Carbonyls | Elevated in atherosclerosis and heart failure; Correlates with disease severity [10] | Significantly increased in AD brain and MCI; Redox proteomics identifies specific oxidized proteins [12] | Higher in diabetic patients; Associated with hyperglycemia and complications [4] |

| 3-Nitrotyrosine | Increased in atherosclerotic plaques; Associated with endothelial dysfunction [10] | Elevated in AD brain; Detected in neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques [12] | Elevated in diabetic vasculature; Contributes to insulin resistance [4] [10] |

| 4-HNE-Adducts | Detected in oxidized LDL and atherosclerotic lesions; Promotes endothelial apoptosis [10] | Increased in AD brain; Modifies key enzymes involved in energy metabolism [12] | Forms adducts in pancreatic islets; Impairs insulin secretion [4] |

| AOPP | Accumulates in plasma of CVD patients; Promotes inflammation [10] | Elevated in AD and Parkinson's disease; Correlates with cognitive decline [12] | Higher in diabetic nephropathy; Serves as renal damage marker [4] |

DNA Oxidation Markers

Formation Mechanisms and Key Biomarkers

Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA are vulnerable to oxidative damage, leading to mutations, impaired transcription, and genomic instability [11]. The hydroxyl radical (HO•) is particularly reactive with DNA, causing various base modifications and strand breaks [13] [11].

Key biomarkers include:

- 8-Hydroxy-2'-Deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): The most extensively studied DNA oxidation product, formed by HO• attack at the C8 position of deoxyguanosine [4] [13]. It is a predominant form of ROS-induced DNA damage.

- 8-Hydroxyguanosine (8-OHG): The RNA equivalent of 8-OHdG, indicating oxidative damage to RNA [10].

- Purine 5',8-Cyclo-2'-Deoxynucleosides (cPu): Intrastrand cross-linked lesions (cdA and cdG) formed exclusively by HO• attack, repaired only by nucleotide excision repair (NER) [11].

- 8-Oxo-7,8-Dihydro-2'-Deoxyadenosine (8-oxo-dA): An oxidation product of adenine that pairs with cytosine, leading to G→T transversion mutations [11].

- Strand Breaks and Abasic Sites: Result from direct radical attack on the sugar-phosphate backbone or as intermediates of DNA repair [13].

Experimental Detection and Analysis

Accurate measurement of oxidized DNA bases requires sensitive techniques to avoid artifactual oxidation during sample preparation.

Standard Protocols:

- Sample Preparation: DNA extraction using chaotropic methods (e.g., sodium iodide) with antioxidant chelators (e.g., deferoxamine) to prevent spurious oxidation [13].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Isolated DNA is digested to nucleosides using nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase for LC-MS analysis.

- Analysis:

- LC-MS/MS: The most specific and reliable method for simultaneous quantification of multiple DNA lesions (8-OHdG, 8-oxo-dA, cPu) without derivatization [4] [11].

- HPLC with Electrochemical Detection (HPLC-ECD): Highly sensitive for 8-OHdG detection, though with lower specificity than MS methods [4].

- Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS): Requires derivatization but provides comprehensive profiling of various modified bases [12].

- ELISA: Commercial kits available for 8-OHdG, enabling high-throughput analysis but with potential cross-reactivity issues [4] [13].

- Comet Assay (Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis): Detects overall DNA damage, including strand breaks and alkali-labile sites, at single-cell level [13].

Disease Associations and Research Applications

DNA oxidation biomarkers reflect cumulative oxidative damage to the genome and are associated with disease risk, progression, and aging.

Table 3: DNA Oxidation Biomarkers in Chronic Diseases

| Biomarker | Cardiovascular Diseases | Neurodegenerative Diseases | Diabetes/Metabolic Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-OHdG | Significantly elevated in heart failure (ROM=2.24 vs controls) [13]; Associated with atherosclerosis progression [10] | Increased in AD brain, CSF, and plasma; Correlates with cognitive decline [12] | Elevated in diabetic patients; Predictive for nephropathy development [4] |

| 8-OHG | RNA oxidation in vascular cells; Contributes to endothelial dysfunction [10] | Widespread RNA oxidation in AD brain; Impairs protein synthesis [12] | Increased in pancreatic β-cells under hyperglycemia [4] |

| cPu Lesions | Accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques due to inefficient repair [11] | Detected in AD brain; Persistent due to poor repair in neurons [11] | Potential marker for cumulative oxidative damage in diabetes [11] |

| Telomere Attrition | Shorter telomeres in heart failure (ROM=0.66) and atherosclerosis [13] [10] | Associated with accelerated aging in neurodegenerative diseases [10] | Accelerated shortening in diabetes; Links oxidative stress to cellular aging [4] |

Comparative Analysis Across Biomarker Classes

Technical Comparison and Research Considerations

Each biomarker class offers distinct advantages and limitations for research applications, influencing their selection for specific study designs.

Table 4: Technical Comparison of Oxidative Stress Biomarker Classes

| Parameter | Lipid Peroxidation Products | Protein Modifications | DNA Oxidation Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability | Variable: Some products (MDA) are reactive; Others (IsoPs) are stable [14] | Generally stable: Protein carbonyls and 3-NT are relatively long-lived [16] | Relatively stable with careful sample processing to prevent artifactual oxidation [11] |

| Sensitivity | High for MS-based methods (low nM-pM range) [14] [15] | Moderate to high: Immunoassays less sensitive than MS methods [16] | Very high: MS methods can detect 1-10 lesions/10⸠nucleotides [11] |

| Specificity | Varies: IsoPs specific to free radical damage; HODEs can distinguish oxidation mechanisms [14] | Moderate: Protein carbonyls are general markers; 3-NT more specific to peroxynitrite [12] | High: 8-OHdG specific to oxidative damage; cPu exclusive to HO• attack [11] |

| Sample Types | Plasma, urine, tissues, CSF [14] [15] | Plasma, tissues, cells, CSF [12] [16] | Blood cells, urine, tissues, isolated DNA [13] [11] |

| Key Advantages - Gold standards exist (F2-IsoPs); - Multiple pathways yield diverse markers; - Can assess antioxidant efficacy [14] | - Direct link to functional impairment; - Redox proteomics identifies specific targets; - Stable cumulative markers [12] [16] | - Direct genotoxic damage assessment; - Strong association with mutation risk; - Urinary 8-OHdG non-invasive [13] [11] | |

| Major Challenges - Complex sample preparation; - Artificial oxidation during processing; - Multiple isomers require separation [14] | - Low abundance in circulation; - Requires specific antibodies; - Site-specific analysis technically demanding [16] | - High risk of artifactual oxidation; - Requires rigorous sample handling; - Low abundance necessitates sensitive detection [11] |

Integrated Oxidative Stress Assessment

Combining multiple biomarker classes provides a comprehensive assessment of oxidative stress status in chronic diseases. The simultaneous measurement of lipid, protein, and DNA oxidation products reveals different aspects of oxidative damage dynamics and compensatory mechanisms [10]. For instance, in Alzheimer's disease research, elevated F2-isoprostanes (lipid), protein carbonyls (protein), and 8-OHdG (DNA) in the same patients provide compelling evidence for widespread oxidative damage [12]. Similarly, in heart failure, concurrent increases in MDA, protein carbonyls, and 8-OHdG highlight the multi-faceted nature of oxidative stress in disease progression [13] [10].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

Oxidative stress biomarkers are not merely passive indicators of damage but active participants in cellular signaling pathways that influence disease progression.

Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Signaling Pathways: This diagram illustrates how reactive oxygen species (ROS) generate different classes of oxidative biomarkers, which in turn participate in and amplify cellular stress pathways through complex feedback mechanisms that influence disease progression [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful measurement of oxidative stress biomarkers requires specific reagents and methodologies optimized for each biomarker class.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Reagent/Methodology | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Systems (LC-MS/MS, GC-MS) | Gold-standard quantification of IsoPs, HODEs, 8-OHdG, protein carbonyls [14] [11] [15] | High specificity and sensitivity; Requires technical expertise; Enables multiplexing of different biomarkers |

| Anti-DNP Antibodies | Detection of protein carbonyls after DNPH derivatization (ELISA, Western blot) [12] | Broad specificity for carbonylated proteins; Quality varies between vendors; Requires proper controls |

| Anti-3-Nitrotyrosine Antibodies | Specific detection of protein nitration (IHC, Western blot, ELISA) [12] | Specificity confirmation essential; May require epitope retrieval for tissue samples |

| Anti-8-OHdG Antibodies | Immunoassays for DNA oxidation (ELISA, IHC) [13] | Potential cross-reactivity with normal nucleosides; Requires careful DNA isolation |

| DNA Digestion Enzymes (Nuclease P1, Alkaline Phosphatase) | Sample preparation for MS-based DNA oxidation analysis [11] | Enzyme purity critical to prevent artifactual oxidation; Include antioxidant in buffers |

| Reducing Agents (NaBHâ‚„, Triphenylphosphine) | Stabilization of lipid hydroperoxides to alcohols before analysis [14] | Fresh preparation essential; Control reduction efficiency |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up and concentration before analysis [15] | Improve sensitivity and remove interfering compounds; Select appropriate phase chemistry |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (dâ‚„-8-iso-PGF₂α, ¹âµNâ‚…-8-OHdG) | MS quantification for improved accuracy [14] [15] | Correct for recovery losses and matrix effects; Essential for precise quantification |

| Calphostin C | Calphostin C, CAS:121263-19-2, MF:C44H38O14, MW:790.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pbox-15 | Pbox-15, CAS:354759-10-7, MF:C28H19NO3, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis of lipid peroxidation products, protein modifications, and DNA oxidation markers reveals distinct yet complementary perspectives on oxidative stress in chronic diseases. Lipid peroxidation biomarkers, particularly F2-isoprostanes, offer sensitive indicators of early oxidative damage and are established gold standards in cardiovascular and neurodegenerative research [14] [15]. Protein oxidation markers provide direct links to functional impairment of enzymes and cellular structures, with redox proteomics enabling identification of specifically modified proteins in conditions like Alzheimer's disease [12] [16]. DNA oxidation markers, especially 8-OHdG, represent genotoxic consequences of oxidative stress with strong implications for genomic instability and cellular aging across multiple chronic conditions [13] [11].

The selection of appropriate biomarkers should be guided by research objectives, with multi-class biomarker approaches providing the most comprehensive assessment of oxidative stress status. As methodologies advance, particularly in mass spectrometry-based techniques, simultaneous quantification of multiple biomarkers across classes is becoming increasingly feasible, offering powerful tools for understanding oxidative mechanisms in disease pathogenesis and evaluating novel antioxidant therapies [14] [11] [15].

The accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and management of complex chronic diseases rely heavily on the identification and interpretation of biomarkers. While conditions such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and chronic kidney disease often coexist and share common pathophysiological pathways, each disorder exhibits a unique molecular signature. Understanding these disease-specific biomarker profiles is critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to develop targeted therapies and precision medicine approaches. This guide provides a structured comparison of characteristic biomarker patterns across these disease domains, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, with a particular focus on their relationship to oxidative stress pathways.

Comparative Biomarker Profiles Across Disease Domains

The tables below synthesize key biomarker patterns across cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal conditions, highlighting their clinical relevance and disease-specific associations.

Table 1: Core Pathophysiological Processes and Representative Biomarkers by Disease Domain

| Disease Domain | Core Pathophysiological Processes | Representative Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress | suPAR, Galectin-3, GDF-15, MDA, 8-OHdG, F2-isoprostanes [17] [4] |

| Metabolic (MetS) | Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, central obesity, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress | Leptin, Adiponectin, IL-6, TNF-α, Oxidized LDL, Uric acid, LysoPC a C18:2 [18] [19] |

| Renal (CKD) | Glomerular & tubular injury, fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress | KIM-1, NGAL, Cystatin C, suPAR, TGF-β1, IL-6, TNF-α [20] [21] [22] |

Table 2: Characteristic Biomarker Patterns and Functional Roles in Specific Diseases

| Biomarker | Cardiovascular Conditions | Metabolic Conditions | Renal Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| suPAR | Predicts atherosclerosis & coronary artery calcification; marker of systemic inflammation [17] | Associated with metabolic disorders & insulin resistance [17] | Strongly associated with CKD progression & glomerular dysfunction [17] [21] |

| Galectin-3 | Key regulator of cardiac fibrosis & remodeling; prognostic in heart failure [17] | Linked to hepatic fibrosis in MASLD [17] | Associated with kidney disease progression & fibrosis [17] |

| GDF-15 | Implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction & cardiovascular aging [17] | Elevated in metabolic stress & insulin resistance [17] | Not a primary renal biomarker |

| KIM-1 | Not a primary cardiovascular biomarker | Not a primary metabolic biomarker | Urinary marker of tubular injury; predicts CKD progression [20] [21] |

| NGAL | Not a primary cardiovascular biomarker | Not a primary metabolic biomarker | Marker of acute & chronic kidney damage; predicts CKD progression [20] [21] |

| LysoPC a C18:2 | Not a primary cardiovascular biomarker | Negatively associated with MetS & all 5 components; potential protective role [19] | Not a primary renal biomarker |

| Amino Acids (e.g., BCAA, Phe) | Not a primary cardiovascular biomarker | Positively associated with MetS; indicates impaired catabolism [19] | May be altered in uremic milieu |

| MDA / 8-OHdG | Elevated; indicates lipid peroxidation & DNA damage in hypertension [4] | Elevated; indicates systemic oxidative stress [18] | Elevated; indicates oxidative kidney injury [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Analysis

Protocol for Oxidative Stress Biomarker Measurement

The following protocol is adapted from clinical studies evaluating oxidative stress in chronic disease populations, including long COVID and metabolic syndrome [5] [4].

- Sample Collection: Collect blood samples (e.g., 5 mL) and process to obtain serum or plasma. For urinary DNA damage markers, collect mid-stream urine. Store aliquots at -80°C until analysis.

- Measurement of Oxidative Stress (d-ROMs Test):

- Principle: Measures hydroperoxides which react via the Fenton reaction to generate radicals that oxidize an amine substrate, creating a colored complex [5].

- Procedure: Add serum to a buffered reagent containing the chromogen. Incubate and measure absorbance photometrically at 505 nm. Results are expressed in Carratelli Units (CARR U) [5].

- Measurement of Antioxidant Capacity (BAP Test):

- Calculation of Oxidative Stress Index (OSI): OSI = C × (d-ROMs / BAP), where C is a standardization coefficient [5].

- Advanced Oxidative Damage Assays:

- Lipid Peroxidation: Malondialdehyde (MDA) can be measured via the Thiobarbituric Acid-Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay. F2-isoprostanes, more stable end-products, are quantified using gas or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS-MS) for high specificity [4].

- DNA Oxidation: 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is quantified using HPLC with electrochemical or mass spectrometry detection (HPLC-ECD or HPLC-MS/MS) or via ELISA kits [4].

Protocol for Multiplexed Kidney Biomarker Analysis

This protocol details the simultaneous measurement of a 21-protein panel in plasma and urine, as used in studies characterizing AKI and CKD/ESKD [22].

- Sample Preparation:

- Plasma: Collect blood via phlebotomy into appropriate tubes. Centrifuge to isolate plasma, aliquot, and freeze at -80°C. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

- Urine: Collect mid-stream urine or from an indwelling catheter. Centrifuge to remove debris, aliquot the supernatant, and freeze at -80°C.

- Multiplex Immunoassay Procedure:

- Bead Addition: Add 50 μL of the mixed capture beads to each well of a 96-well plate.

- Washing: Wash the plate using a magnetic plate washer.

- Sample & Standard Incubation: Add 25 μL of Universal Assay Buffer to each well, followed by 25 μL of sample (undiluted plasma/urine or pre-diluted, as optimized) or standard. Incubate for 60 minutes at room temperature with shaking.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: After washing, add 25 μL/well of biotinylated detection antibody mix. Incubate for 30 minutes with shaking.

- Streptavidin-PE Incubation: After washing, add 50 μL/well of Streptavidin-PE solution. Incubate for 30 minutes with shaking.

- Reading: After a final wash, add Reading Buffer and analyze the plate on a compatible Luminex system (e.g., Bio-Plex 200) [22].

- Data Analysis: Use instrument software to calculate concentrations from standard curves. Apply statistical and machine learning models to identify diagnostic profiles.

Integrated Pathophysiological Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected pathways and biomarkers shared across cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal systems, highlighting oxidative stress as a central mechanism.

Diagram: Interconnected Pathways in Chronic Disease. This diagram shows how oxidative stress acts as a central driver of key pathophysiological processes (center), which in turn promote tissue damage in cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal systems (bottom). Characteristic biomarkers for each process are shown (right).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomarker Profiling

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| AbsoluteIDQ p150/p180 Kit | Targeted metabolomics for simultaneous quantification of amino acids, acylcarnitines, lipids, etc. | LysoPC a C18:2, Branched-chain amino acids, Glycine [19] |

| Human ProcartaPlex Kidney Panels | Multiplex immunoassays for simultaneous protein biomarker quantification in plasma/urine. | KIM-1, NGAL, Cystatin C, TFF3, β2-microglobulin [22] |

| d-ROMs & BAP Test Kits | Photometric assays for determining oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity. | Hydroperoxides, Biological Antioxidant Potential [5] |

| Luminex xMAP Instrumentation | Platform for fluorescent bead-based multiplex immunoassays. | suPAR, Galectin-3, Cytokines [22] |

| HPLC-ECD / HPLC-MS/MS | High-sensitivity quantification of specific oxidative damage molecules. | 8-OHdG, F2-isoprostanes [4] |

| Troponin I Immunoassay | Gold-standard immunoassay for myocardial injury. | Troponin I (not covered in detail, but critical for CVD) [23] |

| Pci 29732 | Pci 29732, CAS:330786-25-9, MF:C22H21N5O, MW:371.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quarfloxin | Quarfloxin, CAS:865311-47-3, MF:C35H33FN6O3, MW:604.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the cellular world, two transcription factors, Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) and Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2), serve as central regulators of the body's response to inflammation and oxidative stress. These systems are not isolated; they engage in extensive crosstalk, forming a coordinated defense network [24] [25]. Dysregulation of the delicate balance between NF-κB-driven inflammation and Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response is a hallmark of numerous chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [24] [26] [25]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two pivotal signaling pathways, offering experimental data and methodologies relevant for researchers and drug development professionals working in the field of oxidative stress.

Comparative Analysis of Nrf2 and NF-κB Pathways

The following tables provide a structured comparison of the core structural components, regulatory mechanisms, and functional roles of the Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways.

Table 1: Core Structural Components and Regulatory Mechanisms

| Feature | Transcription Factor Nrf2 | Transcription Factor NF-κB |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Family | Cap'n'Collar (CNC) subfamily of basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors [24] [27] | NF-κB/Rel family [28] |

| Key Domains | Seven Nrf2-ECH homology (Neh) domains (Neh1-Neh7). Neh1 contains CNC-bZIP region; Neh2 contains DLG/ETGE motifs for Keap1 binding [24] [27] | Rel Homology Domain (RHD) for dimerization, DNA binding, and nuclear localization [24] [28] |

| Primary Inhibitor | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) in the cytoplasm [24] [29] [27] | Inhibitor of κB (IκB), most commonly IκBα [24] [28] |

| Regulatory Mechanism (Basal State) | Keap1 promotes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Nrf2, keeping it at low levels [24] [27] | IκB binds to and sequesters NF-κB in the cytoplasm, preventing its nuclear translocation [24] [28] |

| Activation Trigger | Oxidative stress, electrophiles [24] | Pro-inflammatory cytokines, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [25] |

| Activation Mechanism | Stress modifies Keap1 cysteine residues, disrupting Nrf2 ubiquitination. Nrf2 stabilizes, translocates to nucleus, forms heterodimer with sMaf, and binds ARE [24] [28] | Activators trigger IκB Kinase (IKK). IKK phosphorylates IκB, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation. NF-κB dimer translocates to nucleus [24] [28] |

| Key Downstream Targets | Antioxidant genes: HO-1, NQO1, GCL, GSTs [24] [30] | Pro-inflammatory genes: TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, CRP [25] |

Table 2: Functional Roles in Health and Disease

| Aspect | Nrf2 Pathway | NF-κB Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Master regulator of antioxidant and cytoprotective responses; maintains redox homeostasis [24] [29] | Master regulator of innate and adaptive immune and inflammatory responses [24] [25] |

| Role in Disease Pathogenesis | Deficiency/Low Activity: Linked to increased susceptibility to oxidative damage, inflammation, and diseases like Alzheimer's and CAD [30] [25]Hyperactivation: Associated with cancer progression and chemoresistance [27] | Overactivation: Drives chronic inflammation, contributing to atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer [24] [25] |

| Therapeutic Goal | Activation is desirable for cytoprotection in neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases [27] [25] | Inhibition is often the goal to curb chronic inflammation in autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases [25] |

| Key Experimental Biomarkers | - mRNA/protein levels of Nrf2, Keap1 [27]- ARE-reporter gene activity [29]- Target gene expression: HO-1, NQO1 [24] [29] | - mRNA/protein levels of NF-κB subunits (p65, p50) [25]- NF-κB DNA-binding activity (EMSA) [25]- Cytokine levels: TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β [25] |

The Critical Crosstalk Between Nrf2 and NF-κB

The Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways do not operate in isolation but engage in a complex, bidirectional crosstalk that is crucial for integrating the cellular response to stress [24] [25] [28]. This interplay represents a key regulatory node in disease pathogenesis and a potential therapeutic target.

- Nrf2 Antagonizes NF-κB Signaling: Nrf2 activation can suppress NF-κB signaling through multiple mechanisms. By enhancing the expression of antioxidant enzymes like HO-1 and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), Nrf2 reduces the oxidative stress that acts as a potent activator of NF-κB [25] [28]. Furthermore, HO-1 and its metabolic products can directly inhibit NF-κB activation [28]. Some evidence also suggests Nrf2 can compete with NF-κB for the transcriptional coactivator CBP, thereby limiting NF-κB-driven gene expression [28].

- NF-κB Inhibits Nrf2 Activity: The influence is mutual. NF-κB can suppress the Nrf2 pathway, potentially by recruiting histone deacetylases to the antioxidant response element (ARE), leading to transcriptional repression [24]. This creates a vicious cycle where inflammation begets more oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant defense.

- SIRT6 as a Regulatory Node: Recent research highlights SIRT6, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, as a key regulator of this crosstalk. SIRT6 can activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway while simultaneously suppressing NF-κB signaling and its downstream inflammatory cytokines, thereby attenuating both oxidative stress and inflammation in conditions like coronary artery disease [25].

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

Assessing Nrf2 Signaling Activity

Objective: To evaluate the activation status of the Nrf2 pathway in cell culture models treated with a compound of interest (e.g., sulforaphane).

Methodology:

- Cell Lysis and Fractionation: Lyse treated cells and perform cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation using commercially available kits.

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Targets: Probe for Nrf2 in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. An increase in the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic Nrf2 ratio indicates activation [29].

- Key Downstream Proteins: Probe for classic Nrf2 target proteins like HO-1 and NQO1 in whole cell lysates [24].

- Loading Controls: Use Lamin B1 for nuclear fractions and α-Tubulin for cytoplasmic fractions.

- Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR):

- Measure mRNA expression levels of Nrf2 target genes (e.g., HMOX1, NQO1, GCLC) to confirm transcriptional activation [24].

- Reporter Gene Assay:

- Transfert cells with a plasmid containing the ARE promoter linked to a luciferase reporter gene. Treat with the test compound and measure luciferase activity as a direct readout of Nrf2-mediated transcription [29].

Evaluating NF-κB Signaling Activity

Objective: To determine the effect of a pro-inflammatory stimulus (e.g., TNF-α) on NF-κB pathway activation.

Methodology:

- Immunofluorescence (IF):

- Seed cells on coverslips, treat with stimulus, and fix. Stain with an antibody against the p65 subunit of NF-κB and a fluorescent secondary antibody. Use DAPI to stain nuclei.

- Analysis: Visualize using fluorescence microscopy. In unstimulated cells, p65 is cytoplasmic. Upon activation, p65 translocates to the nucleus, visible as DAPI co-localization [24].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA):

- Isolate nuclear extracts from treated cells. Incubate with a labeled DNA probe containing the NF-κB consensus binding sequence.

- Analysis: Run on a native gel. A shift in the probe's mobility indicates NF-κB binding to the DNA, confirming activation [25].

- ELISA for Cytokines:

- Collect cell culture supernatant after treatment.

- Use specific ELISA kits to quantify the secretion of NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [25].

Measuring Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

Objective: To quantify oxidative stress levels in patient plasma or cell culture supernatant.

Methodology:

- Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay:

- Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay:

- Principle: SOD is a key antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals.

- Protocol: Use a commercial SOD activity kit, typically based on the ability of SOD to inhibit the oxidation of a tetrazolium salt by superoxide anion generated by a xanthine/xanthine oxidase system [31].

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Nrf2 Signaling and Regulation

Nrf2 Pathway Regulation

NF-κB Signaling Pathway

NF-κB Pathway Activation

Nrf2/NF-κB Crosstalk

Nrf2/NF-κB Crosstalk

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Nrf2 and NF-κB Pathways

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Application | Specific Example Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Western Blot/IF | Detect protein expression, localization, and post-translational modifications. | Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, NQO1, NF-κB p65, Phospho-IκBα, IκBα [24] [25] |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits | Quantify secreted inflammatory mediators in cell supernatant or serum. | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β [25] |

| ARE Reporter Plasmid | Measure Nrf2 transcriptional activity in a high-throughput manner. | Firefly luciferase gene under control of ARE promoter [29] |

| Nuclear Extraction Kit | Isolate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions to study transcription factor translocation. | Analysis of Nrf2 and NF-κB nuclear import [29] |

| Commercial Activity Assay Kits | Quantify oxidative stress markers and antioxidant enzyme activity. | MDA (Lipid Peroxidation), SOD Activity, GSH/GSSG Ratio [31] |

| Pathway Agonists & Antagonists | Experimentally manipulate pathway activity for functional studies. | Nrf2 Agonists: Sulforaphane [29]IKK/NF-κB Inhibitors: BAY 11-7082 |

| Quinacainol | Quinacainol, CAS:86073-85-0, MF:C21H30N2O, MW:326.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quinagolide hydrochloride | Quinagolide hydrochloride, CAS:94424-50-7, MF:C20H34ClN3O3S, MW:432.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

NF-κB and Nrf2 represent two pivotal, interconnected transcriptional pathways that coordinate the cellular response to inflammation and oxidative stress. Their antagonistic crosstalk is a critical determinant of cellular fate in chronic disease. A deep understanding of their distinct mechanisms, regulatory nodes like SIRT6, and the experimental tools to study them is essential for advancing therapeutic strategies. Future research will continue to elucidate the complexity of this interaction, paving the way for novel interventions that can precisely modulate this balance to treat cancer, neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases.

The Inflammation-Oxidative Stress Nexus represents a fundamental, self-amplifying biological circuit in which reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory mediators engage in reciprocal regulation, driving the pathogenesis of numerous chronic diseases. This intricate crosstalk creates a vicious cycle where ROS activate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, and the resulting inflammatory response, in turn, stimulates further ROS production [33]. This nexus is not merely sequential but synergistic, establishing pathogenic loops that sustain chronic inflammation in conditions ranging from cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders to cancer and metabolic diseases [34] [35]. Understanding the molecular architecture of this interplay—specifically the cytokine networks and their interaction with reactive species—provides critical insights for therapeutic intervention in chronic disease pathology.

The balance between oxidative and reductive forces (redox balance) is crucial for maintaining physiological homeostasis. However, emerging evidence suggests that deviations to either extreme—oxidative stress (OS) or the less-appreciated reductive stress (RS)—can disrupt immune function and contribute to disease progression [34]. This review examines the molecular machinery of this nexus, compares oxidative stress markers across disease contexts, details experimental approaches for its study, and explores therapeutic implications for drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways and Transcription Factors

Reactive Oxygen Species as Pro-Inflammatory Signaling Molecules

Reactive oxygen species, including superoxide anion (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), function as crucial second messengers in cellular signaling while also serving as damaging agents in excess [33] [36]. These molecules originate from multiple cellular sources:

- Mitochondria: The electron transport chain, particularly complexes I and III, constitutes the primary endogenous source of ROS, where electron leakage to oxygen generates superoxide anions [34] [37].

- NADPH Oxidases (NOX): Enzyme systems dedicated to ROS production, with NOX2 playing a central role in the oxidative burst essential for microbial killing in phagocytes [34] [38].

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Oxidative protein folding during ER stress generates Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ release through enzymes like Ero1 and protein disulfide isomerase [34].

The dual nature of ROS—as signaling mediators and damaging agents—depends on their concentration, spatial localization, and temporal dynamics [36]. At physiological levels, ROS facilitate normal cellular proliferation and differentiation, but when produced excessively, they trigger oxidative damage and activate inflammatory pathways [38].

Key Redox-Sensitive Transcription Factors

Table 1: Major Redox-Sensitive Transcription Factors in the Inflammation-Oxidative Stress Nexus

| Transcription Factor | Activation Trigger | Key Target Genes | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | ROS-mediated IκB phosphorylation | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, COX-2, iNOS | Pro-inflammatory cytokine production, inflammasome activation |

| Nrf2 | Oxidative modification of Keap1 cysteine residues | HO-1, NQO1, GCLC, GST | Antioxidant response element (ARE) activation, cytoprotection |

| HIF-1α | ROS inhibition of PHD enzymes | VEGF, glycolytic enzymes | Angiogenesis, metabolic adaptation, inflammation |

| AP-1 | ROS activation of MAPK pathways | MMPs, cyclin D1, pro-inflammatory cytokines | Proliferation, tissue remodeling, inflammation |

| NLRP3 | ROS-induced TXNIP dissociation from Trx1 | IL-1β, IL-18 | Inflammasome assembly, inflammatory cell death (pyroptosis) |

The NF-κB pathway represents the most well-characterized redox-sensitive inflammatory pathway [34] [33]. ROS activate IκB kinase (IKK), leading to phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, which frees NF-κB dimers (p65/p50) to translocate to the nucleus and promote transcription of pro-inflammatory genes encoding cytokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes like COX-2 and iNOS [34] [33]. This pathway establishes a feed-forward loop where NF-κB target genes, particularly those encoding cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β, further stimulate ROS production from immune cells.

The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway functions as a critical protective axis against oxidative stress [34] [33]. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to Keap1 and targeted for ubiquitination and degradation. OS modifies critical cysteine residues on Keap1, leading to Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation, where it binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs) and induces transcription of cytoprotective genes including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) [34]. Nrf2 activation not only mitigates oxidative damage but also exerts anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing NF-κB-driven transcription [34] [33].

A pivotal mechanism in the oxidative-inflammatory network is the reciprocal regulation between NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways [33]. These transcription factors compete for limited co-activators, such as CREB-binding protein (CBP), and exert mutually antagonistic effects. NF-κB activation suppresses Nrf2-mediated transcription by sequestering CBP, thereby limiting the antioxidant response. Conversely, Nrf2 activation reduces oxidative burden and inhibits NF-κB signaling through suppression of IKK activity [33].

Figure 1: Core Signaling Circuitry of the Inflammation-Oxidative Stress Nexus. ROS activate both pro-inflammatory NF-κB and antioxidant Nrf2 pathways. NF-κB induces cytokine production that further stimulates ROS generation, creating an amplification loop, while Nrf2 induces antioxidants that neutralize ROS. The pathways exhibit reciprocal inhibition, competing for transcriptional co-activators.

Comparative Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers Across Chronic Diseases

The assessment of oxidative stress in clinical and research settings relies on measuring specific molecular biomarkers that reflect oxidative damage to cellular components. The table below summarizes key oxidative stress biomarkers and their alterations across major chronic disease categories.

Table 2: Oxidative Stress Biomarkers Across Chronic Diseases: Comparison and Clinical Utility

| Biomarker | Molecular Nature | Analytical Methods | Disease Contexts & Alterations | Research & Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Lipid peroxidation product | TBARS assay, HPLC, LC-ESI-MS/MS | ↑ CVD, CKD, CCHS, NASH, neurodegenerative diseases | Gold standard lipid peroxidation marker; urinary MDA useful for risk stratification in CCHS [39] |

| 8-Hydroxy-2'-Deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) | Oxidized DNA nucleoside | ELISA, HPLC-ECD, GC/MS | ↑ Cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, CVD | Sensitive marker of oxidative DNA damage; correlates with disease progression [36] |

| F2-Isoprostanes | Prostaglandin-like compounds from lipid peroxidation | GC/MS, LC-MS/MS | ↑ Diabetes, obesity, neurodegenerative diseases | Robust marker of lipid peroxidation; not artifactual; elevated in AD, diabetes [36] [26] |

| 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal (HNE) | Reactive aldehyde from lipid peroxidation | Immunohistochemistry, LC-MS/MS | ↑ AD, PD, metabolic diseases, cancer | Highly reactive; modifies proteins, DNA; implicated in neurodegeneration, carcinogenesis [26] |

| Protein Carbonyls | Oxidatively modified proteins | DNPH assay, Western blot | ↑ Pulmonary fibrosis, aging, neurodegenerative diseases | Marker of protein oxidation; L. minor extract reduces levels in bleomycin-induced fibrosis [39] |

| Cys34 Albumin Oxidation | Oxidized thiol on plasma albumin | Mass spectrometry | ↑ Duchenne muscular dystrophy (mdx mice) | Blood biomarker reflecting muscle protein thiol oxidation; superior to protein carbonylation in DMD [39] |

| 8-iso-PGF2α | Isoprostane from lipid peroxidation | GC/MS, immunoassays | ↑ Diabetes, atherosclerosis, renal disease | Reliable in vivo oxidant stress marker; elevated in diabetic complications [32] |

The comparative analysis of these biomarkers across diseases reveals both common and pathology-specific patterns of oxidative damage. For instance, lipid peroxidation products (MDA, HNE, F2-isoprostanes) show consistent elevation across cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative conditions, suggesting shared mechanisms of oxidative membrane damage [39] [26]. In contrast, Cys34 albumin oxidation appears particularly valuable for monitoring dystrophic pathology in Duchenne muscular dystrophy, indicating its potential as a disease-specific biomarker [39].

The context-dependent utility of these markers is exemplified by urinary MDA monitoring in Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS), where it serves as a key biomarker of oxidation for patient risk stratification [39]. Similarly, plasma Cys34 albumin thiol oxidation more closely reflects changes in protein thiol oxidation in dystrophic muscle than the more commonly used protein carbonylation, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate biomarkers for specific pathological contexts [39].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Assessing the Nexus

Standard Protocols for Oxidative Stress Biomarker Assessment

Lipid Peroxidation Measurement via MDA Quantification The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay represents a widely used method for assessing lipid peroxidation through malondialdehyde (MDA) detection [39] [36]. The protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue or biofluid in PBS containing butylated hydroxytoluene (0.01%) to prevent artificial lipid peroxidation during processing.

- Reaction Mixture: Combine 100μL sample with 200μL of 8.1% SDS, 1.5mL of 20% acetic acid (pH 3.5), and 1.5mL of 0.8% thiobarbituric acid.

- Incubation: Heat mixture at 95°C for 60 minutes, then cool on ice.

- Extraction & Measurement: Centrifuge at 3,000g for 15 minutes, measure supernatant absorbance at 532nm. Quantify MDA using molar extinction coefficient of 1.56×10âµ Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹.

- Advanced Validation: For improved specificity, employ LC-ESI-MS/MS with DNPH derivatization, particularly in complex matrices like exhaled breath condensate [39].

Protein Carbonyl Content Determination Protein carbonyls serve as reliable markers of protein oxidation. The standard DNPH-based protocol includes:

- Derivatization: React protein samples (1mg/mL) with 10mM 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) in 2M HCl for 60 minutes in darkness.

- Protein Precipitation: Add 20% trichloroacetic acid, incubate on ice for 15 minutes, then centrifuge at 11,000g for 10 minutes.

- Washing: Wash pellet three times with ethanol:ethyl acetate (1:1) to remove free DNPH.

- Solubilization & Measurement: Dissolve final pellet in 6M guanidine hydrochloride, measure absorbance at 370nm. Calculate carbonyl content using molar absorptivity of 22,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹.

Comprehensive Lipidomic Profiling for Lipid Peroxidation Products Advanced mass spectrometry approaches provide detailed assessment of oxidative lipid damage:

- Lipid Extraction: Use modified Bligh-Dyer method with chloroform:methanol (2:1 v/v) containing internal standards.

- LC-MS Analysis: Employ reverse-phase C18 column with gradient elution (water/acetonitrile:isopropanol). Perform nanoESI-MS or LC/MS for intact lipid and lipid hydroperoxide detection [39].

- Data Processing: Use specialized software (e.g., LipidSearch, XCMS) for peak alignment, identification, and quantification. Key peroxidized lipids include triglyceride hydroperoxides (TGOOH) and phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides (PCOOH), identified as diagnostic biomarkers in chronic kidney disease and NASH models [39].

Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating the Nexus

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Detection Probes | DCFH, DHE, BODIPY variants | Cellular ROS measurement, flow cytometry, microscopy | Specificity for different ROS species (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ vs O₂•â»); compartment-targeted probes available [36] |

| Antioxidant Compounds | NAC, quercetin, curcuminoids | Experimental antioxidant interventions | NAC boosts glutathione; quercetin downregulates NOX2-derived ROS, suppresses MAPK/NF-κB [33] [36] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | NOX inhibitors (apocynin), NF-κB inhibitors | Pathway-specific inhibition | Apocynin blocks NOX assembly; NF-κB inhibitors prevent nuclear translocation [34] |

| Cytokine Assays | ELISA, Luminex, ELISA-based cytokine panels | Inflammatory mediator quantification | Multiplex panels enable parallel measurement of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18 in biological samples [34] [38] |

| Nrf2 Activators | Sulforaphane, bardoxolone methyl | Enhancement of antioxidant response | Induce Nrf2 dissociation from Keap1, promote ARE-driven gene expression (HO-1, NQO1) [34] [33] |

| Animal Models of Disease | mdx mice (DMD), BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis, NASH models | Pathophysiological context testing | mdx mice show elevated Cys34 albumin oxidation; bleomycin model demonstrates oxidative protein damage [39] |

Figure 2: Comprehensive Experimental Workflow for Assessing the Inflammation-Oxidative Stress Nexus. The integrated approach combines measurement of reactive species, oxidative damage biomarkers, and inflammatory mediators from biological samples, enabling comprehensive profiling of the redox-inflammatory axis.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting the inflammation-oxidative stress nexus presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development. Conventional antioxidant approaches have demonstrated limited clinical efficacy, likely due to non-specific actions, poor bioavailability, and failure to address the bidirectional nature of redox dysregulation [34] [33]. This has prompted development of more sophisticated strategies:

Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants These compounds (e.g., MitoQ, SkQ1) concentrate in mitochondria, the primary ROS source, offering superior efficacy compared to untargeted antioxidants. In animal models, they improve coronary angiogenesis and cardiac function in mitochondrial infarction [26] [37].

Nrf2 Activators Pharmacological activation of the Nrf2 pathway provides a systems-level approach to enhancing antioxidant capacity. Compounds like bardoxolone methyl induce a coordinated antioxidant response, showing promise in diabetic kidney disease and other oxidative stress-related conditions [33].

Advanced Delivery Systems Nanoparticle-enabled delivery of antioxidants addresses bioavailability limitations. Single-atom nanozymes with catalase-like and SOD-like activity (e.g., Mn-based catalysts) attenuate neuroinflammation and promote blood-brain barrier reconstruction in traumatic brain injury models [26].

Dual-Target Approaches Simultaneous targeting of oxidative and inflammatory pathways may offer synergistic benefits. For instance, nano-formulated curcumin (80mg/day) in multiple sclerosis patients significantly reduced both IL-6 and oxidative markers, indicating dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity [33].

The emerging recognition of reductive stress as a potential pathological state suggests that therapeutic strategies must aim to restore redox homeostasis rather than simply suppress oxidation [34]. Future research directions should include disease-specific redox profiling, development of compartment-specific redox biomarkers, and personalized interventions based on individual redox signatures.

The inflammation-oxidative stress nexus represents a fundamental pathological circuit in chronic diseases, with cytokine networks and reactive species engaging in sophisticated cross-talk. Comprehensive understanding of this interplay, facilitated by the experimental approaches and biomarkers detailed here, provides a roadmap for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that disrupt this vicious cycle and restore physiological redox balance.

Analytical Approaches: Techniques for Measuring Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Research and Clinical Settings

Biomarker quantification is a cornerstone of modern clinical and preclinical research, providing critical data for diagnosing diseases, monitoring treatment efficacy, and understanding pathological mechanisms. Among the plethora of analytical techniques available, Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) have emerged as three cornerstone methodologies. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations, making their selection crucial for research validity, particularly in complex fields like oxidative stress marker analysis in chronic diseases. This guide provides a objective, data-driven comparison of these gold standard methods, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the information needed to select the optimal technology for their specific biomarker quantification needs.

Understanding the fundamental working principles of each technology is essential for appreciating their comparative strengths and applications in biomarker analysis.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) combines the physical separation capabilities of liquid chromatography with the mass analysis capabilities of mass spectrometry. In LC-MS, the sample is dissolved in a liquid mobile phase and separated through a column packed with a stationary phase. The separated analytes are then ionized, most commonly via electrospray ionization (ESI), and the resulting ions are separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and detected [40]. This technique is exceptionally versatile for analyzing a wide range of biomolecules, from small molecules to proteins, without the need for derivatization.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) similarly couples the separation power of gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. However, it requires that analytes be volatile and thermally stable. The sample is vaporized and carried by an inert gas through a column, where separation occurs. The separated components are then ionized, typically by electron impact (EI) or chemical ionization (CI), before mass analysis [41] [40]. For non-volatile compounds, this often necessitates a derivatization step to increase volatility and thermal stability, adding complexity to sample preparation.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is an immunoassay that detects antigen-antibody interactions. It utilizes an enzyme-linked conjugate and a chromogenic substrate that generates a measurable color change. The core principle involves immobilizing an antigen or antibody on a solid phase (typically a 96-well microplate), followed by a series of binding and washing steps. The intensity of the color produced is proportional to the amount of analyte present and is measured spectrophotometrically [42]. Common formats include direct, indirect, and sandwich ELISA, with the latter offering high specificity through the use of two antibodies that "sandwich" the target antigen.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The selection of an analytical platform hinges on its performance characteristics. The table below provides a structured comparison of LC-MS, GC-MS, and ELISA across key parameters, with a focus on implications for oxidative stress biomarker research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of LC-MS, GC-MS, and ELISA for Biomarker Quantification

| Performance Parameter | LC-MS/MS | GC-MS | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (e.g., LOD for cotinine: 0.1 ng/mL) [43] | High (comparable to LC-MS/MS for targeted analytes) [41] | Variable; can be very high (e.g., picomolar range for competitive ELISA); often lower than MS [43] [44] |

| Specificity | Very High (based on mass and fragmentation pattern) | Very High (based on mass and fragmentation pattern) | High, but subject to antibody cross-reactivity [45] [44] |

| Throughput | Moderate to High | Moderate (longer run times and sample prep) [41] | Very High (amenable to full 96-well plates) [42] |

| Sample Preparation | Moderate (e.g., protein precipitation, SPE) [41] | Complex (often requires derivatization) [41] | Simple (often minimal processing required) [42] |

| Analyte Scope | Very Broad (small molecules, lipids, proteins) [40] | Limited to volatile/derivatizable compounds (e.g., steroids, fatty acids) [40] | Broad (proteins, hormones, peptides, antibodies) [42] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited in targeted mode, broader in untargeted | Limited | Available with multiplex immunoassay platforms [46] |

| Cost & Accessibility | High capital cost, requires specialized expertise | High capital cost, requires specialized expertise | Low to moderate cost, widely accessible [43] |

Key Implications for Oxidative Stress Research

- Analyte Scope and Specificity: Oxidative stress encompasses diverse biomarkers, including lipid peroxidation products (e.g., MDA, isoprostanes), DNA adducts (e.g., 8-OHdG), and modified proteins. LC-MS is exceptionally suited for quantifying a wide panel of these metabolites with high specificity, minimizing ambiguity. GC-MS is a robust tool for specific volatile compounds, while ELISA kits are available for many markers but can suffer from cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules [47] [32].

- Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Markers: Many oxidative stress markers circulate at low concentrations. The high sensitivity of LC-MS/MS and GC-MS makes them ideal for detecting these low levels, as demonstrated in studies measuring trace-level environmental exposures [43]. While ELISA sensitivity can be improved via signal amplification, it may not reliably detect very low-level markers in all biological matrices [44].

- Quantification and Standardization: MS-based methods provide absolute quantification using internal standards, which is critical for longitudinal studies and inter-laboratory comparisons. ELISA provides relative quantification against a standard curve, and results can vary significantly between different commercial kits, even for the same analyte, due to differences in antibody specificity [45].

Experimental Protocols and Data Concordance

Empirical comparisons highlight how methodological choice can directly influence research outcomes.

Case Study: Quantifying Cotinine in Saliva

A 2020 study directly compared LC-MS/MS and ELISA for quantifying salivary cotinine, a biomarker for tobacco smoke exposure in children [43].

- Protocol: Saliva samples from 218 children were analyzed in parallel using both LC-MS/MS (with isotope dilution) and a commercial ELISA kit. The limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 0.1 ng/mL for LC-MS/MS and 0.15 ng/mL for ELISA.

- Results: While the intraclass correlation was high (0.884), the geometric mean cotinine concentration measured by LC-MS/MS (4.1 ng/mL) was significantly lower than that from ELISA (5.7 ng/mL). This consistent overestimation by ELISA is attributed to antibody cross-reactivity with other nicotine metabolites like 3'-hydroxycotinine and its glucuronide [43]. Crucially, significant associations between cotinine levels and child sex/race were only detectable using the more sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS data, demonstrating its superior power for revealing subtle exposure-disease relationships.

Case Study: Measuring Vitamin D-Binding Protein (DBP)

A critical comparison of a monoclonal ELISA, a polyclonal ELISA, and LC-MS/MS for measuring DBP revealed profound platform-specific biases [45].

- Protocol: Serum DBP was measured in 125 participants using all three assays. Participants were genotyped for common DBP isoforms (Gc1f, Gc1s, Gc2).

- Results: The monoclonal ELISA (R&D Systems) showed a strong genotype-dependent bias, yielding disproportionately lower concentrations for the Gc1f isoform (common in Black individuals), thereby creating a spurious racial disparity. In contrast, LC-MS/MS and the polyclonal ELISA showed no significant race-based differences [45]. This highlights that immunoassay performance can be critically dependent on the specific antibodies used and the genetic variability of the target protein, a bias that MS methods largely avoid.

Table 2: Summary of Key Comparative Studies Highlighting Platform Concordance and Discordance

| Study Focus | Key Finding | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Cotinine Analysis [43] | ELISA overestimated concentrations vs. LC-MS/MS due to cross-reactivity; LC-MS/MS revealed significant associations with demographics that ELISA missed. | For low-level exposure studies or when metabolite specificity is critical, LC-MS/MS is strongly preferred. |

| DBP Analysis [45] | Monoclonal ELISA, but not polyclonal ELISA or LC-MS/MS, introduced significant genotype-dependent bias in quantification. | Antibody-based assays require rigorous validation against genetic variants; MS provides a more reliable absolute quantitation. |

| Benzodiazepine Analysis [41] | LC-MS/MS and GC-MS showed comparable accuracy and precision, but LC-MS/MS required minimal sample prep and no derivatization. | LC-MS/MS offers a more efficient workflow for high-throughput analysis of labile compounds without sacrificing data quality. |

| Multiplex Protein Detection [46] | In skin tape strips, the MSD platform showed higher detectability of low-abundance proteins than Olink or NULISA platforms. | For complex matrices with low protein yield, platform sensitivity is a primary consideration for successful biomarker detection. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biomarker quantification relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for setting up these analyses.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Quantification

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Corrects for sample matrix effects and variability in sample preparation and ionization. | Critical for LC-MS/GC-MS. Isotope-labeled versions of the analyte (e.g., cotinine-d4) are added to the sample before processing [43] [41]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Purifies and pre-concentrates analytes from complex biological matrices (e.g., urine, plasma). | Used in sample prep for both LC-MS and GC-MS to reduce ion suppression and improve sensitivity [41]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Increases volatility and thermal stability of non-volatile analytes for GC-MS analysis. | Required for many biomarkers (e.g., steroids, organic acids) prior to GC-MS. Example: MTBSTFA [41]. |

| High-Affinity Capture & Detection Antibodies | Binds specifically to the target analyte in a "sandwich" format for high-sensitivity detection. | The core of a sensitive and specific Sandwich ELISA. Monoclonal antibodies offer high specificity [42] [44]. |