Resolving Identifiability Issues in Mathematical Models of Inflammation: A Guide for Robust Quantification

Mathematical modeling is crucial for understanding the complex dynamics of inflammatory responses and developing effective therapeutics.

Resolving Identifiability Issues in Mathematical Models of Inflammation: A Guide for Robust Quantification

Abstract

Mathematical modeling is crucial for understanding the complex dynamics of inflammatory responses and developing effective therapeutics. However, the utility of these models is often compromised by identifiability issues, where model parameters cannot be uniquely or reliably estimated from available data. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing these critical challenges. We explore the foundational concepts of structural and practical identifiability, review advanced methodological and computational tools for analysis, present strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing non-identifiable models, and discuss rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this article serves as a practical resource for developing more reliable, predictive models of inflammation to enhance drug discovery and personalized medicine approaches.

Understanding Identifiability: Why Your Inflammation Model's Parameters Might Be Unknowable

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between structural and practical identifiability?

- Answer: Structural identifiability is a theoretical property of your model's equations. It assesses whether parameters can be uniquely determined from perfect, continuous, and noise-free data. It is a necessary prerequisite for reliable parameter estimation [1] [2] [3]. Practical identifiability, in contrast, concerns whether parameters can be uniquely estimated given your actual data—which is finite, noisy, and collected at specific time points [4] [5]. Even a structurally identifiable model can be practically unidentifiable if the data is insufficient or too noisy to reliably estimate the parameters [6] [5].

FAQ 2: Why should I perform identifiability analysis before fitting my model to experimental data?

- Answer: Conducting identifiability analysis before experiments helps you avoid building models or designing experiments that are fundamentally incapable of providing unique parameter estimates. It saves significant time and resources by [2]:

- Revealing if your model structure is over-parameterized.

- Guiding the selection of measurable outputs.

- Informing experimental design (e.g., when to take samples) to ensure the data collected will be informative.

- Answer: Conducting identifiability analysis before experiments helps you avoid building models or designing experiments that are fundamentally incapable of providing unique parameter estimates. It saves significant time and resources by [2]:

FAQ 3: A parameter in my model is structurally unidentifiable. What are my options?

- Answer: You have several troubleshooting paths:

- Reparameterize the model: Combine unidentifiable parameters into an identifiable composite parameter [2] [6].

- Fix parameter values: If possible, use literature values to set unidentifiable parameters to a constant value [2].

- Modify the model output: Sometimes, measuring an additional variable (e.g., another cytokine in an inflammation model) can render previously unidentifiable parameters identifiable [2].

- Simplify the model: Remove the mechanistic parts that cause unidentifiability if they are not critical to your research question.

- Answer: You have several troubleshooting paths:

FAQ 4: My model is structurally identifiable, but parameters are practically unidentifiable. How can I improve this?

- Answer: Practical unidentifiability is often addressed by improving the data or the estimation process [6] [5]:

- Optimal Experimental Design: Design experiments to maximize the information content in your data, for instance, by sampling during dynamic transition phases rather than at steady state [5].

- Increase Data Quality and Quantity: Collect more data points or reduce measurement noise.

- Use Regularization: Incorporate penalties (e.g., L2 regularization) during estimation to constrain parameter values [6].

- Answer: Practical unidentifiability is often addressed by improving the data or the estimation process [6] [5]:

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Identifiability Problems

Use this guide to diagnose and resolve common identifiability issues in mathematical modeling.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Tools | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large confidence intervals for parameter estimates; small parameter changes drastically worsen fit [5]. | Practical Unidentifiability: Noisy or insufficient data, poor experimental design. | Profile Likelihood [1] [4], Monte Carlo simulations [7] [5], Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) analysis [4] [5]. | Optimal experimental design [5], collect more informative data, use regularization [6]. |

| Parameter estimates change drastically with different initial guesses; optimization fails to converge. | Structural or Practical Unidentifiability. | Structural identifiability tools (e.g., DAISY, StructuralIdentifiability.jl [4] [3] [7]), Profile Likelihood [1]. | First, confirm structural identifiability. If structurally identifiable, see solutions for practical unidentifiability. |

| Strong correlations between different parameter estimates. | Structural Unidentifiability or near-unidentifiability; parameters exist in a sloppy combination [2]. | Correlation matrix analysis, sensitivity analysis [8] [9], FIM eigenvalue decomposition (near-zero eigenvalues) [4] [5]. | Model reparameterization (combine parameters) [2], fix one of the correlated parameters from literature. |

| Good model fit (low error) but biologically implausible parameter values. | Structural Unidentifiability: Multiple parameter sets yield identical output [2]. | Structural identifiability analysis (e.g., Taylor series, EAR approach [2]). | Redesign model structure, impose biologically plausible constraints during estimation, measure additional model outputs. |

Experimental Protocols for Identifiability Analysis

Protocol 1: Profile Likelihood Analysis for Practical Identifiability

This protocol assesses how well a parameter can be identified from a given dataset by exploring the likelihood surface [1] [4].

- Define the Objective Function: Establish a cost function, such as the negative log-likelihood or sum of squared errors, between your model simulation and experimental data.

- Obtain Point Estimate: Find the parameter values that minimize the cost function. This is your best-fit estimate, ( \hat{\theta} ).

- Profile a Parameter: Select a parameter of interest, ( \thetai ). Over a defined range of values for ( \thetai ), for each fixed value, re-optimize the cost function over all other parameters ( \theta_{j \neq i} ).

- Plot and Interpret: Plot the optimized cost function value against the values of ( \theta_i ). A uniquely identifiable parameter will show a sharply peaked profile. A flat or shallow profile indicates practical unidentifiability [1] [5].

Protocol 2: Structural Identifiability Analysis using the Taylor Series Method

This algebraic method checks if the model's output is unique for all possible parameter values, assuming perfect data [2].

- Model Formulation: Express your model in the standard state-space form (ODE system with specified outputs) [2].

- Taylor Series Expansion: Expand the model output ( y(t) ) as a Taylor series around a known time point (typically ( t=0 )), using the model's equations to compute higher-order derivatives.

- Coefficient Comparison: The coefficients of the Taylor series ( (y(0), y'(0), y''(0), \dots) ) are functions of the unknown parameters and initial conditions. The model is structurally globally identifiable if these equations can be solved uniquely for all parameters. If the solution is unique only in a local neighborhood, it is locally identifiable [2].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Identifiability Analysis Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical sequence for diagnosing and resolving identifiability issues in model development.

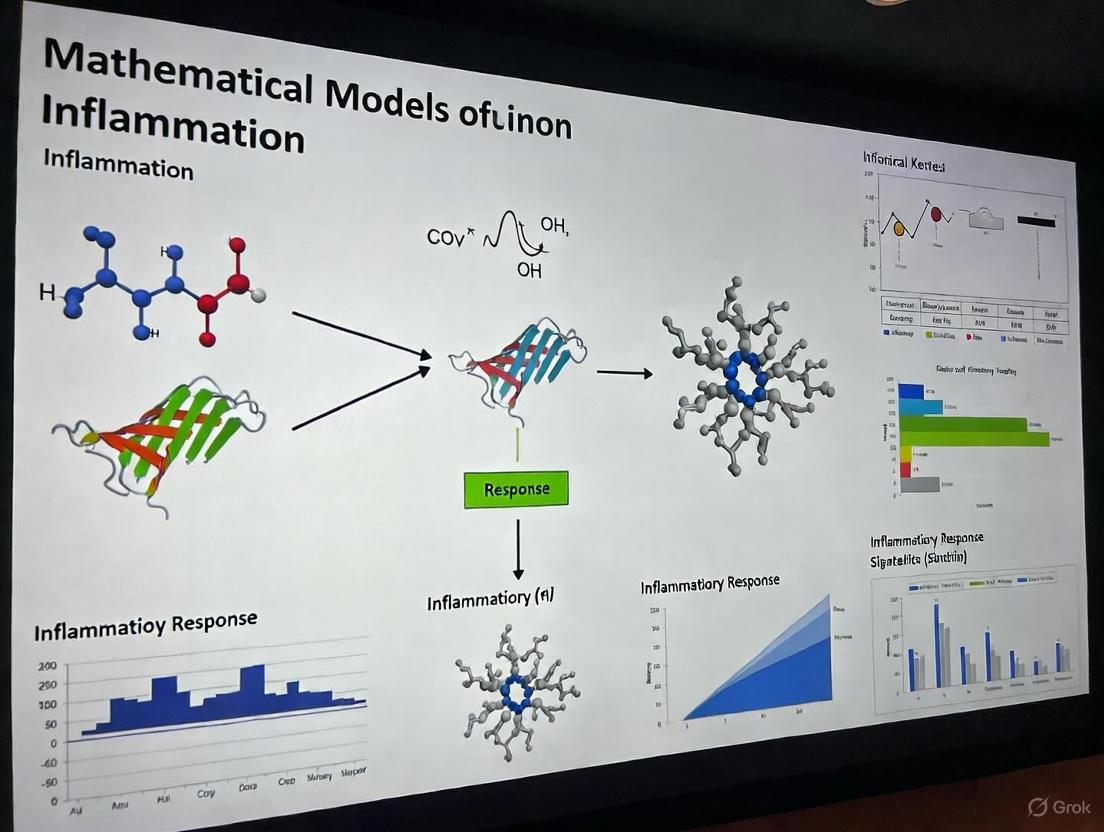

Inflammation Model Component Interactions

This diagram illustrates the core interactions in a typical cytokine-mediated inflammation model, a key application area where identifiability is crucial [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key computational tools and methods for identifiability analysis.

| Tool / Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Profile Likelihood [1] [3] | Assesses practical identifiability by exploring likelihood-based confidence intervals for parameters. | ODE/PDE models; requires a defined cost function and optimization routine. |

| DAISY [4] | Performs structural identifiability analysis using differential algebra. Provides a categorical (yes/no) answer. | Models described by systems of rational ODEs; assumes perfect data. |

| StructuralIdentifiability.jl [3] [7] | A Julia library for assessing structural identifiability using a differential algebra approach. | Handles nonlinear ODE models; useful for complex biological systems. |

| Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) [4] [5] | A matrix whose inverse lower-bounds the covariance of parameters. Near-zero eigenvalues indicate unidentifiable directions. | Local, practical identifiability; requires parameter sensitivities. |

| Sensitivity Matrix Method (SMM) [4] | Analyzes the matrix of output sensitivities to parameters. A non-trivial null space indicates unidentifiability. | Practical identifiability; helps identify correlated parameters. |

| Monte Carlo Simulations [7] [5] | Evaluates practical identifiability by simulating noisy data and assessing the distribution of parameter estimates. | Quantifies robustness of parameter estimation to observational noise. |

| Oxaprotiline | Oxaprotiline, CAS:56433-44-4, MF:C20H23NO, MW:293.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Picrotoxinin | Picrotoxinin, CAS:17617-45-7, MF:C15H16O6, MW:292.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Critical Role of Identifiability in Predictive Immunology

In the field of predictive immunology, mathematical models are indispensable for interpreting complex biological processes, from viral infection dynamics to inflammatory resolution. Identifiability is a fundamental property that determines whether the parameters of a mathematical model can be uniquely estimated from available experimental data [10] [11]. The failure to ensure identifiability can lead to misleading parameter estimates, unreliable biological interpretations, and ultimately, flawed public health or therapeutic recommendations [11] [12].

This technical support center addresses the critical identifiability challenges faced by researchers in mathematical immunology. The guidance herein is framed within the broader thesis that resolving identifiability issues is paramount for developing models with genuine predictive power, particularly in the context of inflammation research.

FAQs: Core Concepts of Identifiability

Q1: What is the difference between structural and practical identifiability?

- Structural Identifiability is a theoretical property of the model itself. A model is structurally identifiable if, given perfect and noise-free experimental data, its parameters can be uniquely determined. This depends on the model's structure, the choice of observables, and the initial conditions of the state variables [10].

- Practical Identifiability refers to the ability to uniquely estimate parameters from real-world data that is typically sparse, noisy, and limited. Even a structurally identifiable model may not be practically identifiable if the available data is insufficient to constrain the parameters [10] [12].

Q2: Why is identifiability analysis crucial for mathematical models of inflammation?

Identifiability analysis is critical because models of immune processes, such as acute infection development or inflammatory resolution, often contain numerous parameters [10] [12]. Without verifying identifiability, researchers risk:

- Drawing incorrect conclusions about underlying biological mechanisms.

- Making unreliable predictions about disease outcomes or therapeutic efficacy.

- Developing models that are over-parameterized and lack predictive value [11] [12].

Q3: What common factors cause identifiability issues in immunological models?

- Model Over-parameterization: Using models with too many parameters relative to the available data [12].

- Inadequate Data: Using data that is sparse in time, has high noise, or lacks critical observables [10] [11] [12].

- Parameter Correlation: Strong dependencies between parameters, such as between the community transmission rate, the fraction of under-reporting, and the proportion of the population with prior immunity, which can make them impossible to estimate jointly from case data alone [11].

- Poor Experimental Design: Initial conditions and measurement protocols that do not provide sufficient information to tease apart parameter values [10].

Q4: How can I resolve the unidentifiability of key parameters in an epidemic model?

A common identifiability problem involves jointly estimating the transmission rate, under-reporting fraction, and prior immunity level from only reported case data, which is often unidentifiable [11]. This can be resolved by complementing the case data with additional information sources. Research shows that identifiability of all three parameters is achieved if reported incidence is complemented with sample survey data of prior immunity or prevalence during the outbreak [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Structural Unidentifiability

Table 1: Strategies to Overcome Structural Unidentifiability

| Problem | Diagnostic Signs | Solution | Protocol/Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Correlation | Parameters cannot be uniquely estimated even with perfect data; profiles are flat [11]. | Reformulate the model or reduce the number of parameters. | Use the profile likelihood approach to detect flat profiles. Fix one correlated parameter to a literature value to test the identifiability of others [11] [12]. |

| Insufficient Observables | Key state variables of the model (e.g., specific immune cell counts) are not measured [10]. | Increase the number of measured outputs. | Design experiments to measure additional model variables. For example, in viral infection models, measure both viral load and Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte (CTL) response kinetics [10]. |

| Complex Model Terms | A model with simple bilinear terms (e.g., for virus-CTL interactions) is not identifiable [10]. | Reparameterize the model with biologically realistic, bounded terms. | Refine bilinear terms to bounded-rate parameterizations, such as Michaelis-Menten-type functions, which can improve structural identifiability [10]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Practical Unidentifiability

Table 2: Strategies to Overcome Practical Unidentifiability

| Problem | Diagnostic Signs | Solution | Protocol/Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy or Sparse Data | Wide confidence intervals for parameter estimates; estimates vary significantly with different data realizations [12]. | Improve data quality and quantity. | Increase the frequency and precision of sampling. Use Bayesian estimation approaches with informative priors where justified to constrain parameter space [10]. |

| Poor Initial Conditions | Parameter estimates are highly sensitive to the initial guess for state variables [10] [12]. | Better initial state determination. | Perform rigorous initial state estimation or design experiments to directly measure initial conditions where possible [10]. |

| Inadequate Data Types | Case data alone is insufficient to identify all parameters of interest [11]. | Integrate multiple data sources. | Combine time-series data (e.g., incidence) with cross-sectional data (e.g., serological surveys for prior immunity or prevalence data) [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Identifiability Analysis

Protocol 1: Structural Identifiability Analysis using Differential Algebra

Purpose: To determine if a system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) is structurally identifiable. Reagents & Tools: Computer with Julia programming environment, StructuralIdentifiability.jl package [10]. Workflow:

- Model Formulation: Define your ODE model, specifying state variables, parameters, and output functions (observables).

- Software Implementation: Code the model into the StructuralIdentifiability.jl package.

- Analysis Execution: Run the package's algorithm (e.g., based on differential algebra or generating series) to obtain identifiability results.

- Result Interpretation: The output will classify each parameter as either "globally identifiable," "locally identifiable," or "unidentifiable."

Structural identifiability analysis workflow.

Protocol 2: Practical Identifiability and Parameter Estimation using Bayesian Methods

Purpose: To estimate model parameters from noisy data and assess their practical identifiability by examining posterior distributions. Reagents & Tools: Computer with Julia/Python/R, DynamicHMC.jl package (or similar MCMC toolbox) [10]. Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Collect and preprocess experimental data (e.g., viral load and CTL response kinetics over time) [10].

- Model Definition: Use a structurally identifiable model.

- Bayesian Estimation: Implement a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampler, such as the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS), to sample from the posterior distribution of the parameters [10].

- Diagnostic Checks: Analyze the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains for convergence. Examine the posterior distributions: well-defined, peaked distributions indicate practical identifiability, while flat or multi-modal distributions suggest unidentifiability.

Practical identifiability analysis with Bayesian methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Modeling and Analysis in Immunology

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| StructuralIdentifiability.jl | A Julia-based package for analyzing the structural identifiability of ODE models. | Used to prove identifiability before costly parameter estimation exercises [10]. |

| DynamicHMC.jl | A Julia package for Bayesian inference using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC). | Enables robust parameter estimation and practical identifiability assessment via posterior distributions [10]. |

| Multiplex Immunoassays | Simultaneously measure concentrations of multiple soluble immune factors (cytokines, chemokines) from serum. | Critical for collecting rich, multi-dimensional data for model fitting (e.g., ProcartaPlex Human Inflammation Panel) [13]. |

| Profile Likelihood | A numerical method for investigating practical identifiability and confidence intervals. | Can reveal parameter correlations and unidentifiability that might be missed by other methods [12]. |

| SIAN (Software for Structural Identifiability Analysis) | Another software tool for structural identifiability analysis of ODE models. | An alternative to StructuralIdentifiability.jl [10]. |

| Naftazone | Naftazone CAS 15687-37-3|Research Chemical | Naftazone, a naphthoquinone derivative for vascular disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Pipobroman | Pipobroman, CAS:54-91-1, MF:C10H16Br2N2O2, MW:356.05 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between structural and practical non-identifiability?

Structural non-identifiability is an inherent property of your model structure, where multiple parameter sets produce identical model outputs even with perfect, continuous, noise-free data. This occurs due to parameter correlations built into the model equations themselves [4]. In contrast, practical non-identifiability arises from limitations in your experimental data—such as sparse sampling times, significant measurement noise, or insufficient data points—which prevent unique parameter estimation despite the model being structurally identifiable [14] [15].

2. How can I detect non-identifiability in my inflammation model?

You can employ several methodological approaches. Collinearity analysis examines parameter correlations by calculating a collinearity index; high values (typically >10-15) indicate strong correlations and potential non-identifiability [16]. Likelihood profiling analyzes the flatness of likelihood curves for each parameter; flat profiles suggest the parameter cannot be uniquely identified [16] [17]. Structural identifiability tools like DAISY or StructuralIdentifiability.jl use differential algebra to provide definitive answers about structural identifiability for ordinary differential equation models [18] [4].

3. Why does my inflammation model with many parameters often become non-identifiable?

Complex inflammation models frequently incorporate numerous poorly constrained parameters while being calibrated against limited experimental data (e.g., only cytokine concentrations). This creates a situation where insufficient calibration targets relative to unknown parameters allows multiple parameter combinations to fit the same data equally well. This is particularly problematic in within-host pathogen models and physiological models of systemic inflammation [16] [14] [19].

4. What are the practical consequences of non-identifiability for drug development?

Non-identifiability can significantly impact decision-making in pharmaceutical development. Different, equally well-fitting parameter sets may produce divergent predictions about treatment effectiveness. For example, one study demonstrated that two different parameter sets fitting the same calibration targets yielded substantially different estimates of treatment benefit (0.67 vs. 0.31 life-years gained), potentially leading to incorrect decisions about treatment prioritization [16].

5. Can I still use a non-identifiable model for predictions?

Yes, but with important caveats. While a non-identifiable model may reliably predict the specific variables it was calibrated against, its predictions for unmeasured variables or different experimental conditions may be highly unreliable [15]. The model's predictive power for a particular variable depends on whether that variable was included in the training data, with successively adding more measured variables improving overall predictive capability [15].

Detection Methods for Non-Identifiability

Table 1: Comparison of Identifiability Analysis Methods

| Method | Type of Identifiability Assessed | Key Principle | Software Tools | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Algebra | Structural | Symbolic computation to eliminate unobserved variables | DAISY, StructuralIdentifiability.jl [18] [4] | A priori analysis of model structure |

| Profile Likelihood | Practical | Examination of parameter likelihood profiles | Custom implementation in MATLAB/R/Python [16] [17] | Assessing identifiability with existing datasets |

| Fisher Information Matrix | Practical | Analysis of curvature in parameter space | R/pharmacometric packages [4] | Experimental design optimization |

| Collinearity Analysis | Both | Examination of parameter correlations | Custom implementation [16] | Diagnosing correlation-based non-identifiability |

| Sensitivity Matrix | Practical | Analysis of output sensitivity to parameters | R/pharmacometric packages [4] | Identifying insensitive parameters |

Table 2: Common Parameter Correlations in Inflammation Models

| Correlation Type | Typical Manifestation | Impact on Model | Resolution Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Correlation | Parameters appearing only as products (e.g., β×π in viral replication models) [14] | Individual parameters cannot be uniquely identified | Rewrite model using composite parameters |

| Sum Correlation | Parameters appearing only in summation | Relative contributions cannot be distinguished | Incorporate prior information on parameter ratios |

| Input-Output Equivalence | Different mechanisms producing identical outputs | Model structure ambiguity | Add intermediate measurements |

| Time-Scale Correlation | Parameters affecting same temporal dynamics | Individual rate constants unidentifiable | Design experiments with multiple time resolutions |

Experimental Protocols for Identifiability Assessment

Protocol 1: Profile Likelihood Analysis for Practical Identifiability

Purpose: To assess practical identifiability of parameters given experimental data.

Materials: Dataset of time-course measurements (e.g., cytokine concentrations, viral titers), mathematical model implemented in suitable software (MATLAB, R, or Python), optimization algorithm.

Procedure:

- Estimate maximum likelihood parameters by fitting your model to the experimental data

- Select a parameter of interest (θ_i) and define a range of values around its optimum

- For each fixed value of θ_i in this range, re-optimize all other parameters to maximize likelihood

- Plot the optimized likelihood values against the fixed θ_i values

- Analyze the shape of the likelihood profile: sharply peaked profiles indicate identifiable parameters, while flat profiles suggest practical non-identifiability [16] [17]

Interpretation: The likelihood profile reveals whether the data contains sufficient information to uniquely estimate each parameter. Flat profiles indicate that the parameter cannot be constrained by the available data.

Protocol 2: Structural Identifiability Analysis with Differential Algebra

Purpose: To determine whether model parameters can be uniquely identified from perfect, noise-free data.

Materials: ODE model of inflammation, StructuralIdentifiability.jl package [18].

Procedure:

- Install StructuralIdentifiability.jl package in Julia

- Define your ODE model, specifying states, parameters, inputs, and observed outputs

- Run the

assess_identifiabilityfunction on your model - Interpret the output, which classifies each parameter as globally identifiable, locally identifiable, or unidentifiable

- For unidentifiable parameters, the software may provide relationships between parameters

Interpretation: Structurally unidentifiable parameters cannot be uniquely estimated even with perfect data, indicating fundamental issues with model structure or observation scheme [18] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Identifiability Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application in Inflammation Models | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| StructuralIdentifiability.jl | Structural identifiability analysis | Analyzing ODE models of cytokine networks [18] | Requires Julia programming knowledge |

| DAISY Software | Structural identifiability via differential algebra | Examining within-host pathogen dynamics models [20] [4] | Handles rational ODE systems |

| Profile Likelihood Methods | Practical identifiability assessment | Determining parameter estimability from noisy data [16] [17] | Can be implemented in multiple environments |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo | Bayesian parameter estimation | Characterizing parameter uncertainties in complex models [15] | Computationally intensive for large models |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Identifying influential parameters | Prioritizing parameters for estimation [4] | Helps focus on identifiable parameters |

| Piprofurol | Piprofurol, CAS:40680-87-3, MF:C26H33NO6, MW:455.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Ppack dihydrochloride | Ppack dihydrochloride, CAS:82188-90-7, MF:C21H33Cl3N6O3, MW:523.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodological Workflows

Diagram 1: Identifiability Assessment Workflow - This diagram illustrates the integrated process for evaluating both structural and practical identifiability in mathematical models of inflammation.

Diagram 2: Resolution Strategies for Non-Identifiability - This decision framework outlines pathways for addressing different types of non-identifiability in inflammation models.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of identifiability issues when fitting within-host viral dynamics models to data?

Identifiability issues commonly arise from two main sources: the model's inherent structure and practical limitations of the available data [14].

- Structural Non-Identifiability: This occurs when the model's structure makes it theoretically impossible to uniquely estimate parameters, even with perfect, noise-free data. A common cause is parameter correlation, where changes in one parameter can be perfectly compensated for by changes in another, leading to the same model output [14]. For example, in basic viral dynamics models, parameters for infection rate and viral production can be correlated.

- Practical Non-Identifiability: This occurs when the model is structurally identifiable, but the available data is too scarce, noisy, or lacks sufficient information to reliably estimate the parameters [14] [21]. For instance, fitting a complex model with many parameters to only viral titer data, without immune cell counts, often leads to practical identifiability problems [14].

FAQ 2: My model is structurally identifiable, but parameter estimates have wide confidence intervals. How can I improve practical identifiability?

If your model is structurally identifiable but parameters are not practically identifiable, consider these strategies:

- Increase Data Frequency and Diversity: Collect data at more time points, especially during dynamic phases like the initial peak and decline of viral load. Incorporate data for additional model variables; for example, using both daily virus titers and adaptive immune cell data significantly improves the practical identifiability of parameters in influenza models [14].

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use Bayesian estimation methods, which allow you to incorporate prior distributions for parameters based on previous studies or biological knowledge. This can constrain the parameter space and improve identifiability [22].

- Optimal Experimental Design: Employ computational frameworks to design experiments that maximize the information gain for parameter estimation. This involves identifying critical time points for data collection that make all model parameters practically identifiable [21].

- Model Reduction: If certain parameters remain non-identifiable, consider whether the model can be simplified by fixing well-known parameters or by using a less complex model structure that still captures the essential biology [14].

FAQ 3: How can I check for identifiability in my mathematical model before conducting expensive experiments?

A rigorous model validation pipeline should be followed before parameter estimation [14] [21]:

- Structural Identifiability Analysis: Use dedicated software tools to check if your model is theoretically identifiable. Tools like

StructuralIdentifiability.jl(Julia) orSIAN(MATLAB) can perform this analysis using differential algebra or other methods [22] [14]. - Practical Identifiability Analysis: After confirming structural identifiability, assess practical identifiability using the available or planned data. Profile likelihood or Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) analysis can be used. A novel framework proves that practical identifiability is equivalent to the invertibility of the FIM [21]. Eigenvalue decomposition of the FIM can pinpoint which specific parameter combinations are non-identifiable [21].

The table below summarizes a typical analysis workflow and its outcomes for different types of within-host models.

Table 1: Identifiability Analysis of Example Within-Host Models

| Model Name | Key Features | Data Used for Fitting | Typical Identifiability Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Target Cell Model | Target cells (T), infected cells (I), virus (V) [14] | Viral titer data | Often structurally identifiable but may suffer from practical non-identifiability due to parameter correlations [14]. |

| Model with Eclipse Phase | Adds eclipse phase (Iâ‚) before productive infection (Iâ‚‚) [14] | Viral titer data | Improved ability to capture delays; however, some parameters related to infected cell loss may still be non-identifiable with virus data alone [14]. |

| Model with Adaptive Immunity | Adds effector CD8+ T cells (E) explicitly [14] | Viral titer + immune cell data | Significantly improved practical identifiability of parameters related to viral clearance and infected cell death when both data types are used [14]. |

| LCMV-CTL Response Model | Models acute LCMV infection with Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTL) [22] | Viral load and CTL kinetics data | Structural identifiability depends on observability and initial conditions. Bayesian approach can estimate posterior distributions, revealing that bilinear terms may need refinement [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

To address identifiability challenges, the design of experiments and model calibration must be meticulous. The following protocol outlines a robust methodology.

Protocol: A Framework for Model Identifiability Analysis and Refinement

Objective: To systematically diagnose and resolve identifiability issues in mathematical models of acute viral infection (e.g., LCMV).

Materials:

- Mathematical model (ODE/PDE system)

- Experimental dataset (e.g., viral titers, immune cell counts)

- Computational software for identifiability analysis (e.g.,

StructuralIdentifiability.jl,SIAN) and parameter estimation (e.g.,DynamicHMC.jlfor Bayesian estimation [22])

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

Structural Identifiability Check:

- Use differential algebraic methods (e.g., via

StructuralIdentifiability.jlpackage) to verify that all model parameters are globally or locally identifiable from the perfect, noise-free model output [22]. - Troubleshooting: If the model is structurally non-identifiable, find the source (e.g., parameter correlations) and propose additional assumptions. This may involve fixing a well-known parameter, simplifying the model, or re-parameterizing it [14].

- Use differential algebraic methods (e.g., via

Practical Identifiability Assessment:

- Using the actual (noisy) experimental data, perform a practical identifiability analysis. A reliable method is to compute the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM). According to recent frameworks, the invertibility of the FIM is a necessary and sufficient condition for all parameters to be practically identifiable [21].

- Perform eigenvalue decomposition (EVD) on the FIM. Eigenvalues equal to zero indicate that the corresponding parameter combinations (eigenvectors) are practically non-identifiable [21].

Addressing Non-Identifiability:

- Optimal Experimental Design: If parameters are not practically identifiable, use an algorithm to find time points for data collection that maximize the information content. The goal is to design an experiment that results in an invertible FIM [21].

- Parameter Regularization: For non-identifiable parameters, incorporate regularization terms based on the eigenvectors from the FIM's EVD. This technique helps constrain the parameter space during fitting, making all parameters practically identifiable [21].

- Bayesian Estimation: Implement a Bayesian approach (e.g., using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo in

DynamicHMC.jl) to estimate posterior distributions for parameters. This explicitly handles uncertainty and incorporates prior knowledge, which can mitigate identifiability problems [22].

Model Refinement:

- The identifiability analysis may suggest model structural flaws. For example, in LCMV models, Bayesian estimation of posterior distributions suggested that a bilinear term for virus-CTL interaction was inadequate and should be refined to a bounded-rate (e.g., Michaelis–Menten) formulation [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and computational tools essential for conducting the experiments and analyses described in this case study.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for LCMV Modeling Studies

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Identifiability Research |

|---|---|---|

| LCMV (Armstrong & Clone 13) | Armstrong strain causes acute infection. Clone 13 strain establishes persistent chronic infection [23]. | Used to generate kinetic data (viral load, immune cell counts) for model calibration and to study acute vs. chronic infection dynamics [22] [23]. |

| P14 TCR-Transgenic Mice | Genetically modified mice with T cell receptors specific for the LCMV glycoprotein peptide GP33-41 [23]. | Provides a traceable population of CD8+ T cells for precise quantification of antigen-specific immune responses, improving data quality for model fitting [23]. |

| Vaccinia virus expressing OVA (VV-OVA) | A virus engineered to express Ovalbumin (OVA) antigen [23]. | Used in challenge experiments to test T cell functionality against new antigens in chronically infected hosts, informing model predictions on immune dysfunction [23]. |

Computational Tool: StructuralIdentifiability.jl |

A Julia-based software package for analyzing structural identifiability of ODE models [22]. | Used for the initial, theoretical check of whether model parameters can be uniquely identified before data collection [22]. |

Computational Tool: DynamicHMC.jl |

A Julia-based package for Bayesian parameter inference using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo [22]. | Estimates posterior distributions of parameters, quantifying uncertainty and helping to resolve practical identifiability issues through prior information [22]. |

| Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells (BMDCs) | Dendritic cells generated in vitro from bone marrow precursors using GM-CSF [23]. | Used to study antigen presentation and T cell priming capacity under different infection conditions (naive, acute, chronic), providing data for modeling immune cell interactions [23]. |

Tools and Techniques: A Practical Toolkit for Identifiability Analysis

Differential Algebra and the Laplace Transform for Structural Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when performing structural analysis on mathematical models of inflammation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My high-index Differential-Algebraic Equation (DAE) model fails during numerical simulation. What structural issue might be causing this? High-index DAEs (index > 1) often lead to numerical instability because they contain hidden constraints that are not explicitly formulated [24]. This is a common problem in models of biological systems like inflammation where conservation laws or rapid equilibria create algebraic dependencies. The dummy derivatives method is a proven technique for index reduction that can resolve this [24].

Q2: How can I determine if my model's parameters are uniquely identifiable from the available experimental data? Perform a structural identifiability analysis before parameter estimation [8]. A profile likelihood analysis can determine if parameters are locally identifiable, which is crucial for ensuring your model yields reliable, unique parameter estimates from cytokine time-series data [8].

Q3: Can the Laplace Transform handle the complex, nonlinear interactions typical of inflammatory signaling pathways? The standard Laplace Transform is most directly applicable to linear, time-invariant systems. For nonlinear model components, a common approach is to analyze the linearized system around a steady state (e.g., homeostasis or a pathological equilibrium) [25] [26]. This facilitates local stability analysis and transfer function representation.

Q4: What is the most efficient way to compute the inverse Laplace Transform for my model's output function? For complex functions where analytical inversion is difficult, numerical techniques for Laplace transform inversion are recommended [26]. These methods allow you to obtain the time-domain solution, which can be directly compared to experimental data on cytokine dynamics.

Common Error Codes and Resolutions

| Error Code / Symptom | Root Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical Instability in DAE Solver | High Index (≥2) problem structure [24] | 1. Apply structural analysis to determine the index.2. Use index reduction algorithms (e.g., dummy derivatives).3. Check for consistent initial conditions. |

| Non-Unique Parameter Estimates | Structural or practical non-identifiability [8] | 1. Conduct a sensitivity analysis.2. Perform a profile likelihood analysis.3. Re-design experiments to collect more informative data. |

| Failure in Symbolic Laplace Transform | Non-rational or highly complex transfer function | 1. Check for linearity and time-invariance of the subsystem.2. Consider partial fraction decomposition.3. Use numerical inversion methods as an alternative [26]. |

| Nebicapone | Nebicapone, CAS:274925-86-9, MF:C14H11NO5, MW:273.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nedaplatin | Nedaplatin, CAS:95734-82-0, MF:C2H8N2O3Pt, MW:303.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Structural Analysis

Protocol 1: Model Identifiability Analysis via Profile Likelihood

This methodology determines if a model's parameters can be uniquely identified from a given set of experimental data [8].

Primary Objective: To establish the practical identifiability of parameters in a mechanistic model of inflammation (e.g., a model featuring TNF, IL-6, and IL-10 dynamics).

Materials and Reagents:

- In silico model implemented in a suitable computational environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python).

- Experimental or synthetic time-course data for model outputs (e.g., cytokine concentrations).

Procedure:

- Parameter Estimation: For a parameter of interest (θ), find its maximum likelihood estimate (MLE), θ*.

- Profiling: Define a series of values for θ around θ*. For each fixed value of θ, re-optimize all other model parameters to minimize the goodness-of-fit measure.

- Threshold Analysis: Plot the optimized goodness-of-fit against the fixed values of θ. A uniquely identifiable parameter will show a well-defined minimum.

- Iteration: Repeat the profiling process for all unknown parameters in the model.

Protocol 2: DAE Index Reduction using the Dummy Derivatives Method

This protocol outlines the steps to reduce the index of a high-index DAE system to an index-1 problem or an ODE, making it solvable with standard numerical integrators [24].

Primary Objective: To convert a high-index DAE model into a numerically solvable form without altering the system's inherent dynamics.

Materials and Reagents:

- The high-index DAE system definition.

- Computer algebra system (e.g., Mathematica, Maple, or symbolic toolboxes).

Procedure:

- Structural Analysis: Analyze the system equations to identify the key constraints and their derivatives.

- Differentiate Constraints: Select and differentiate the algebraic constraints that are necessary to reduce the index.

- Introduce Dummy Derivatives: Define new variables (the "dummy derivatives") to represent the time derivatives of the algebraic variables.

- System Replacement: Replace the original algebraic equations with their differentiated forms and append the definitions of the dummy derivatives to the system.

- Consistency Check: Ensure that the initial conditions for the new, larger system are consistent with the original constraints.

Model Analysis Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for analyzing a model's structure and identifiability before proceeding with simulation and parameter fitting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and mathematical "reagents" essential for the structural analysis of models in inflammation research.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Application in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Dummy Derivatives Method | A systematic algorithm for reducing the index of a high-index DAE system [24]. | Enables stable simulation of complex cytokine networks with fast equilibrium steps. |

| Laplace Transform | Converts linear differential equations into algebraic equations in the s-domain, simplifying solution finding and analysis of system structure [25] [26]. | Analyzing the input-output response (e.g., LPS stimulus to TNF output) of a linearized inflammation subsystem. |

| Profile Likelihood Analysis | A statistical method for assessing practical (numerical) identifiability of model parameters [8]. | Determining if cytokine decay rate parameters can be uniquely estimated from time-course data. |

| Transfer Function | An s-domain representation (ratio of output to input) that defines the dynamic characteristics of a linear system [26]. | Quantifying the gain and phase shift between an inflammatory stimulus and a specific cytokine output. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Quantifies how changes in model parameters affect model outputs [8] [9]. | Identifying which reaction rate most strongly influences peak IL-6 concentration, guiding targeted interventions. |

| Nefazodone | High-purity Nefazodone HCl for psychiatric research. A SARI compound for studying depression mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | |

| PR-619 | PR-619, CAS:2645-32-1, MF:C7H5N5S2, MW:223.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is StructuralIdentifiability.jl and why is it important for modeling inflammatory diseases?

StructuralIdentifiability.jl is a Julia package that determines whether parameters in mathematical models can be uniquely identified from ideal, noise-free data. For inflammation research, this is a crucial prerequisite before estimating parameters from experimental measurements. It ensures that your model's parameters for immune response dynamics, cytokine production, or complement activation are theoretically determinable, preventing unreliable conclusions from clinical or experimental data [27] [4] [28].

2. My model involves non-integer exponents, which is common in phenomenological growth models of disease. Can I analyze it with this package?

Yes, but it requires reformulation. You can introduce additional state variables to handle non-integer power exponents, making the model compatible with the differential algebra methods used by StructuralIdentifiability.jl. This approach has been successfully applied to models like the Generalized Growth Model (GGM) and Generalized Richards Model (GRM) in epidemiology [7].

3. What is the difference between the assess_identifiability and assess_local_identifiability functions?

assess_identifiability: Checks for global identifiability. If a parameter is globally identifiable, its true value can be uniquely determined from the data.assess_local_identifiability: Checks for local identifiability. A locally identifiable parameter's value can be determined down to a finite number of possibilities within a local region [28]. For model development, it is recommended to check global identifiability first.

4. The analysis indicates some parameters are unidentifiable. What are my options? When parameters are unidentifiable, you can:

- Find Identifiable Combinations: Use the

find_identifiable_functionsfunction. This will find combinations of parameters (e.g., sums or products) that are identifiable, even if individual parameters are not [27]. - Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use the

known_pargument to specify any parameters whose values are already known from previous literature or experiments. This can make other parameters identifiable [28]. - Adjust Measured Quantities: If possible, change or add to the model outputs you plan to measure experimentally.

5. How reliable are the results from this package?

The algorithms used are randomized but provide a very high probability of correctness. By default, the probability threshold is set to 99%. You can increase this bound (e.g., to 99.9%) using the prob_threshold argument, making the results even more conservative [27] [28].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Installation fails or the package does not precompile correctly.

- Solution: Ensure you are using a compatible version of Julia. The package is regularly updated, so check the GitHub repository for the latest version requirements. Start a fresh Julia session and try:

Problem: The analysis is taking too long or running out of memory for a large ODE model.

- Solution: The computational complexity depends on the model structure.

- Simplify the model: Consider if all components are essential for your research question. Reduced-order modeling has been successfully used in complex immune system models [29].

- Check local identifiability first: Use

assess_local_identifiability, which is often less computationally expensive than the global analysis [27]. - Use the

funcs_to_checkargument: Instead of analyzing all parameters, you can specify a subset of critical parameters to check, which speeds up the process [28].

Problem: The package reports that key parameters in my inflammation model are unidentifiable.

- Solution: This is a fundamental mathematical issue, not a software bug. Follow this diagnostic workflow:

- Verify observed quantities: Confirm that the

measured_quantitiesyou have defined correspond to biologically plausible measurements (e.g., serum cytokine levels, viral load). - Check for over-parameterization: Does your model have more parameters than the data can support? Compare your model's complexity to validated models of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 or sepsis [30] [31].

- Reformulate the model: Unidentifiable parameters may indicate a structural flaw. Consult the literature; for example, identifiability analysis has been used to refine COVID-19 models [30] [32].

- Verify observed quantities: Confirm that the

Problem: I receive an error about "non-rational function" when defining my model.

- Solution: The underlying differential algebra methods require models defined by rational functions (ratios of polynomials). If your model contains non-rational terms (e.g.,

sqrt,exp), you may need to reformulate it or use an approximation. The reformulation strategy used for non-integer exponents in growth models can serve as inspiration [7].

Essential Workflow and Protocols

Basic Protocol for Structural Identifiability Analysis

- Model Definition: Define your ODE model using the

@ODEmodelmacro or create aReactionSysteminCatalyst.jl[27] [28]. - Specify Observed Quantities: Declare which model variables or combinations of variables correspond to measurable outputs using the

measured_quantitiesargument. In inflammation models, these could be viral load, interleukin concentrations (e.g., IL-6), or T cell counts [30]. - Declare Known Parameters: Use the

known_pargument to specify any parameters with values fixed from prior knowledge. - Run Identifiability Analysis: Execute

assess_identifiabilityorassess_local_identifiabilityon your model. - Interpret Results: The output is a dictionary classifying each parameter and state as

:globallyidentifiable,:locallyidentifiable, or:nonidentifiable.

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key steps and decision points in this process.

Protocol for Integrating Analysis with Inflammation Research

This protocol connects identifiability analysis directly with experimental research on inflammation, providing a methodology to ensure model parameters for immune responses can be determined from typical experimental measurements [30] [31].

- Define the Pathophysiological Context: Clearly state the inflammatory condition being modeled (e.g., sepsis, SARS-CoV-2 infection, acute pancreatitis).

- Map Biology to Mathematics: Formulate the ODE model, incorporating key immune components (e.g., innate/adaptive immunity, specific cytokines, tissue damage).

- Align with Experimental Data: Define

measured_quantitiesbased on available or planned experimental data (e.g., viral load from PCR, IL-6 from serum ELISA, immune cell counts from flow cytometry). - Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use

known_pto fix parameter values obtained from published literature or previous experiments. - Execute Identifiability Analysis: Run the analysis using the basic protocol.

- Iterate and Validate: If unidentifiable parameters are found, refine the model or measurement strategy. Validate the final identifiable model against unseen experimental data [30] [29].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Identifiability

The following table details key software and computational "reagents" essential for performing robust identifiability analysis in mathematical immunology.

| Item/Software | Primary Function | Relevance to Inflammation Modeling |

|---|---|---|

StructuralIdentifiability.jl |

Core engine for determining structural identifiability of ODE model parameters. | Foundational for ensuring immune response model parameters (e.g., viral replication rates, immune cell activation) are theoretically measurable from data [27] [32]. |

Catalyst.jl |

A Julia package for modeling and simulating chemical reaction networks. | Provides a high-level interface to define reaction network models of biochemical inflammation pathways (e.g., complement system, cytokine signaling) and seamlessly connect them to StructuralIdentifiability.jl [28]. |

| BioGears Physiology Engine | A whole-body, open-source mathematical model of human physiology. | Serves as a platform for building and testing complex, multi-compartment models of systemic inflammatory conditions like sepsis, linking immune dynamics to clinical physiology [31]. |

| BioUML Platform | An open-source platform for systems biology and kinetic modeling. | Used in developing and calibrating modular immune response models, such as for COVID-19, facilitating model reuse and integration into larger frameworks like a Digital Twin [30]. |

| Differential Algebra Method | The underlying mathematical methodology used by StructuralIdentifiability.jl. |

Provides the theoretical foundation for eliminating unobserved state variables (e.g., internal cellular states) to determine parameter identifiability from observable outputs (e.g., blood cytokine levels) [4] [7]. |

Data Presentation: Key Identifiability Analysis Outputs

The output of an identifiability analysis is a classification of model quantities. The table below summarizes the possible results and their implications for your research.

| Classification | Meaning | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Globally Identifiable | The parameter's value can be uniquely determined from the perfect data. | Ideal outcome. You can proceed with parameter estimation from experimental data with high confidence. |

| Locally Identifiable | The parameter's value can be determined, but only down to a finite number of possibilities in a local region. | Acceptable outcome. Parameter estimation is possible but may be sensitive to initial guesses for the optimizer. |

| Nonidentifiable | The parameter's value cannot be determined from the data; infinitely many values can produce the same model output. | Problematic outcome. The model or data collection strategy must be revised (e.g., by finding identifiable combinations or measuring additional quantities) before reliable parameter estimation is possible [27] [28]. |

Advanced Configuration and Optimization

Handling Complex Observations: The measured_quantities argument can accept algebraic expressions, not just single variables. This is useful if your experimental assay measures a sum of species (e.g., total versus phosphorylated protein) [28].

Targeted Analysis for Large Models: For large models, use the funcs_to_check argument to analyze only a specific subset of parameters or custom expressions, significantly reducing computation time [28].

Global Sensitivity Analysis with RS-HDMR for High-Dimensional Models

Mathematical models of acute inflammation are crucial for understanding the complex dynamics of immune responses to infection and injury. These models typically consist of numerous coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with many uncertain parameters [33]. A significant challenge in this field is parameter identifiability - the difficulty in determining unique parameter values that generate model outputs consistent with experimental data. Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA) using Random Sampling-High Dimensional Model Representation (RS-HDMR) has emerged as a powerful approach to address these identifiability issues by systematically quantifying how parametric uncertainties affect model outputs [33] [34].

The complex, non-linear nature of inflammation has made it difficult to directly translate results from animal studies to clinical trials [33]. Traditional local sensitivity methods, which vary one parameter at a time while keeping others constant, are insufficient for capturing the complex parameter interactions characteristic of biological systems. Variance-based global methods like RS-HDMR provide a more comprehensive approach by exploring the entire parameter space simultaneously, making them particularly suitable for high-dimensional models of inflammatory processes [33] [35].

Core RS-HDMR Methodology

Theoretical Foundation

RS-HDMR is a metamodeling technique that approximates the input-output relationship of complex models by decomposing the model output variance into contributions from individual parameters and their interactions [35]. The fundamental HDMR equation represents the model output ( f(x) = f(x1, \ldots, xn) ) as:

[ f(x) = f0 + \sum{i=1}^n fi(xi) + \sum{1 \leq i < j \leq n} f{ij}(xi, xj) + \cdots + f{12 \ldots n}(x1, x2, \ldots, xn) ]

where:

- ( f_0 ) denotes the zeroth-order mean effect

- ( fi(xi) ) represents the first-order contribution of parameter ( x_i )

- ( f{ij}(xi, xj) ) captures the second-order interaction effects between parameters ( xi ) and ( x_j )

- Higher-order terms represent increasingly complex interactions [35]

For most practical applications, including inflammation models, the expansion can be truncated at the second order while maintaining sufficient accuracy, significantly reducing computational complexity [35].

RS-HDMR Algorithm Workflow

Table: Key Steps in RS-HDMR Implementation

| Step | Description | Considerations for Inflammation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Space Definition | Establish bounds for all model parameters based on biological knowledge | Use wide bounds to account for parametric uncertainty in biological systems |

| Sample Generation | Create input parameter samples using Monte Carlo or quasi-random sequences (Sobol' sequence recommended) | 10³-10ⴠsamples typically sufficient for models with 50+ parameters [33] |

| Model Evaluation | Run the model for each parameter set to generate output data | Parallel computing essential for computationally expensive models |

| Metamodel Construction | Build approximate functions using orthonormal polynomials | Second-order expansion often captures >95% of output variance [35] |

| Sensitivity Index Calculation | Compute variance-based Sobol' indices from component functions | Identify parameters driving uncertainty in inflammatory damage metrics |

Troubleshooting Common RS-HDMR Implementation Issues

Insufficient Metamodel Accuracy

Problem: The RS-HDMR metamodel explains less than 90% of output variance, indicating poor approximation of the original model.

Solutions:

- Increase sample size by 25-50% and reassess metamodel performance

- Check parameter bounds for biological plausibility; overly wide bounds can reduce metamodel accuracy

- Consider increasing the expansion order to third-order terms for highly nonlinear systems

- Implement the D-MORPH-HDMR extension, which improves accuracy with limited samples by solving linear algebraic equations with constrained solutions [36]

Verification Protocol:

- Generate a new validation set of 100-200 parameter samples

- Compare outputs from original model and RS-HDMR metamodel

- Calculate R² values for each model output of interest

- Accept metamodel if R² > 0.9 for all critical outputs [35]

Computational Resource Limitations

Problem: Model evaluation time prohibits the required number of Monte Carlo samples.

Solutions:

- Implement the Morris screening method as a preliminary step to identify and fix non-influential parameters [35]

- Use quasi-random Sobol sequences instead of random sampling for better coverage with fewer samples [35]

- Employ parallel computing frameworks to distribute model evaluations across multiple processors

- For extremely computationally intensive models, use a two-stage approach: initial screening with fewer samples followed by focused RS-HDMR on influential parameters

Interpretation of Sensitivity Indices

Problem: Confusion in ranking parameters based on first-order versus total-effect sensitivity indices.

Guidance:

- First-order indices (( S_i )) measure the individual contribution of each parameter to output variance

- Total-effect indices (( S_{Ti} )) include both individual and all interaction effects

- Parameters with large differences between ( Si ) and ( S{Ti} ) participate in significant interactions

- For identifiability analysis, focus on parameters with high first-order indices as they are independently identifiable

- Parameters with low first-order but high total-effect indices may require dedicated experiments to resolve interactions [33] [35]

RS-HDMR Application to Inflammation Models: Case Examples

Acute Inflammatory Response to LPS

In a study of acute inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), researchers applied RS-HDMR to a 51-parameter ODE model to identify key drivers of whole-animal damage and dysfunction [33]. The analysis revealed that inflammatory damage was highly sensitive to parameters affecting IL-6 activity during different stages of acute inflammation, highlighting this cytokine as a critical control point [33].

Table: Key Sensitive Parameters in LPS-Induced Inflammation Model

| Parameter Category | Sensitivity Ranking | Biological Process | Identifiability Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 production and clearance | High | Pro-/anti-inflammatory balance | Critical |

| Nitric Oxide (NO) synthesis | Medium-High | Anti-inflammatory response | High |

| TNF-α dynamics | Medium | Early pro-inflammatory signaling | Medium |

| IL-10 regulation | Medium | Anti-inflammatory feedback | Medium |

| Neutrophil recruitment | Low-Medium | Innate immune response | Low |

The RS-HDMR analysis further revealed bimodal behavior in the system, where the Area Under the Curve for IL-6 (AUCIL6) showed two distinct peaks representing healthy response and sustained inflammation [33]. This finding demonstrated how RS-HDMR can identify critical transitions in inflammatory outcomes.

Genetic Circuit Optimization

While not specific to inflammation, a study optimizing genetic circuits demonstrated RS-HDMR's capability to guide biological engineering [34]. The method correctly identified that inverter output was more sensitive to mutations in the ribosome-binding site upstream of the cI coding region than mutations in the OR1 region of the PR promoter [34]. This approach can be adapted for identifying optimal intervention targets in inflammatory signaling networks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What sample size is needed for reliable RS-HDMR analysis of inflammation models? For typical inflammation models with 50-100 parameters, 1000-5000 samples generally provide sufficient accuracy. Start with 1000 samples and increase until metamodel R² > 0.9. The exact requirement depends on the degree of nonlinearity and parameter interactions in your specific model [35].

Q2: How does RS-HDMR compare to other GSA methods for identifiability analysis? RS-HDMR provides several advantages: (1) It requires only one set of Monte Carlo samples, unlike traditional Sobol' method which needs multiple specialized samples; (2) It simultaneously generates a accurate metamodel for further analysis; (3) It efficiently handles high-dimensional spaces with parameter interactions [35]. For inflammation models specifically, RS-HDMR has successfully identified key regulatory parameters missed by local methods [33].

Q3: Can RS-HDMR handle correlated parameters common in biological systems? Standard RS-HDMR assumes parameter independence. For correlated parameters, extended methods like covariance-based HDMR are available [35]. In practice, for mild correlations, the standard method often remains effective, but strong correlations should be addressed through model reparameterization or using specialized correlation-handling extensions.

Q4: What software tools are available for implementing RS-HDMR? The GUI-HDMR software package (MATLAB-based) provides a user-friendly implementation with graphical interface [35]. For programming-based approaches, Python and R implementations are available through various scientific computing libraries. Custom implementation is also feasible based on the mathematical framework described in the literature [35].

Q5: How can RS-HDMR results guide experimental design in inflammation research? RS-HDMR sensitivity indices directly identify which biochemical parameters most influence model outputs. This allows prioritization of measurement efforts for parameters with high sensitivity indices, significantly improving model identifiability. For example, in inflammation models, IL-6-related parameters often show high sensitivity, guiding targeted experiments to better quantify IL-6 dynamics [33].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Key Resources for RS-HDMR in Inflammation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Tools | GUI-HDMR (MATLAB) | User-friendly RS-HDMR implementation | Ideal for researchers with limited programming experience [35] |

| D-MORPH-HDMR extension | Enhanced accuracy with limited samples | Particularly useful for computationally expensive models [36] | |

| Custom Python/R scripts | Flexible implementation for specific needs | Requires programming expertise but offers maximum flexibility | |

| Experimental Reagents | LPS preparations | Inducing inflammatory response in experimental models | Enables model calibration and validation [33] [8] |

| Cytokine measurement assays | Quantifying TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 dynamics | Critical for parameter estimation in inflammation models [33] | |

| Immune cell isolation kits | Studying specific cell population dynamics | Enables cell-specific parameter estimation |

Workflow Visualization

RS-HDMR Identifiability Enhancement Workflow

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent advances in RS-HDMR methodology have expanded its applications in inflammation research. The integration of information-theoretic approaches with mathematical modeling shows promise for deciphering causal relationships in inflammatory networks, such as connections between arachidonic acid metabolism and cytokine secretion [37]. Additionally, the development of multi-scale inflammation models that incorporate cellular, tissue, and whole-organism levels presents new challenges and opportunities for RS-HDMR application [8].

Future methodological developments should focus on:

- Enhanced computational efficiency for large-scale models

- Improved handling of parameter correlations common in biological systems

- Integration with machine learning approaches for pattern recognition in sensitivity results

- Application to personalized medicine through patient-specific parameterization

As mathematical models of inflammation continue to increase in complexity, RS-HDMR and related global sensitivity analysis methods will remain essential tools for addressing fundamental identifiability challenges and translating computational insights into biological understanding and therapeutic applications.

Bayesian Approaches and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo with DynamicHMC.jl

Troubleshooting Guides

Failed to Find Valid Initial Parameters

Problem: Your sampler fails with an error stating it failed to find valid initial parameters in {N} tries [38].

Explanation: This error occurs when the Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampler cannot locate a starting position where both the log probability density and its gradient are finite and not NaN [38]. In the context of inflammation models, this often happens when parameters fall outside biologically plausible ranges.

Common Causes and Solutions:

NaNGradients: Often caused by invalid parameter values in distributions or functions [38].- Diagnosis: Manually evaluate your model's gradient at different parameter values.

- Solution: Check for problematic constructions like

truncated(Normal(0,1), Inf, Inf). Remove unnecessary bounds or useBijectors.jlfor constrained parameters [38].

-InfLog Density: Occurs when initial parameters place the model in an impossible biological state [38].- Example: In inflammation models, this might happen if a cytokine concentration is initialized as negative.

- Solution: Override the default initialization strategy. Instead of

InitFromUniform(-2, 2), specify biologically plausible initial ranges [38]:

HMC Gets Stuck at Tiny Local Maxima

Problem: Your chains appear to converge to different regions of parameter space in different runs, even though the posterior appears unimodal [39].

Explanation: This behavior, where "HMC saw the posterior as multimodal" despite visual evidence to the contrary, can occur due to several factors [39]:

Solutions:

Reparameterization: Transform parameters to make the posterior geometry more friendly for HMC [39] [40].

- For concentration parameters bounded at

[0, ∞), use a logarithmic transform. - For proportions bounded at

[0, 1], use a logit transform.

- For concentration parameters bounded at

Jittering: Add random noise to the step size to help escape flat regions [40].

Curvature Adaptation: Ensure you're using sufficient warmup samples for the sampler to adapt to the local curvature of your inflammation model [40].

ForwardDiff Type Errors

Problem: You encounter MethodError: no method matching Float64(::ForwardDiff.Dual{...}) when using automatic differentiation [38].

Explanation: This occurs when your model code contains type-unstable operations that cannot handle the ForwardDiff.Dual number types used for automatic differentiation [38].

Solutions:

- Ensure Type Stability: Use

DynamicPPL.DebugUtils.model_warntypeto check for type instabilities in your model [41]. - Avoid Type Annotations: Don't force specific types like

Vector{Float64}in your model code. - Use AD-Compatible Functions: Ensure all functions in your model (including custom ones) can handle

Dualnumbers.

Frequently Asked Questions

How should I handle parameter constraints in inflammation models?

Answer: Use TransformVariables.jl in combination with TransformedLogDensities.jl for domain transformations [42]. For example:

- Cytokine concentrations (must be positive): Use

logtransform - Probability parameters (bounded [0,1]): Use

logittransform - Correlation parameters: Use appropriate constraints for valid matrices

This approach automatically handles the Jacobian corrections required for proper sampling [42].

Why is my model suddenly slow after a small change?

Answer: Small changes can significantly impact performance through [41]:

- Introducing type instability

- Switching between vectorized and scalar operations

- Breaking compiler optimizations

- Causing AD backend incompatibilities

Diagnosis: Use DynamicPPL.DebugUtils.model_warntype to check for type instability and profile your log-density function to identify bottlenecks [41].

Can I use threading within my DynamicHMC model?

Answer: Yes, but with important caveats [41]:

observestatements (likelihood): Generally safe in threaded loopsassumestatements (priors/sampling): Often crash unpredictably or produce incorrect results- AD backend compatibility: Many automatic differentiation backends don't support threading

For safe parallelism, prefer vectorized operations over explicit threading with Threads.@threads [41].

Experimental Protocols for Inflammation Models

Parameter Identifiability Analysis

Purpose: Determine which parameters in your inflammation ODE model can be uniquely identified from available data [8].

Protocol:

- Local Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate partial derivatives of model outputs with respect to parameters [8]

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: Profile out each parameter while optimizing others [8]

- Identifiability Classification:

- Structurally identifiable: Parameters that are theoretically unique

- Practically identifiable: Parameters that can be estimated with available data quality

- Unidentifiable: Parameters that cannot be uniquely determined

Implementation:

Model Calibration with Experimental Data

Purpose: Estimate identifiable parameters using combined in vitro and in vivo data [8].

Protocol:

- Parameter Subset Selection: Based on sensitivity analysis, select parameters for estimation [8]

- Multi-Stage Calibration:

- First, use in vitro data to inform cellular-level parameters

- Then, use human endotoxemia data for system-level parameters [8]

- Validation: Test calibrated model against held-out data (different LPS dosages or infusion protocols) [8]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Bayesian Inflammation Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DynamicHMC.jl [43] | No-U-Turn Sampler implementation | Robust posterior sampling for complex models |

| TransformVariables.jl [42] | Domain transformation with Jacobian correction | Handling biologically constrained parameters |

| LogDensityProblems.jl [42] | Standard interface for log-posteriors | Creating compatible target distributions |

| ForwardDiff.jl [38] | Automatic differentiation | Gradient calculation for HMC |

| ProfileLikelihood.jl | Parameter identifiability analysis | Determining which parameters are estimable |

| Turing.jl [38] [41] | Probabilistic programming | Alternative interface for model specification |

Workflow Visualization

Bayesian Workflow for Inflammation Models

DynamicHMC.jl Sampling Process

Inflammation Model Structure

FAQ: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What is a Hybrid Neural ODE (HNODE), and why is it relevant for inflammation research? A Hybrid Neural ODE (HNODE) is a modeling framework that integrates partially known mechanistic Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models with neural networks. The neural network acts as a universal approximator to represent unknown biological processes or unmodeled dynamics within an otherwise mechanistic system [44]. In inflammation research, where mechanisms are often only partially understood, this approach allows you to leverage established biological knowledge (e.g., core cytokine interactions) while using data to learn the missing pieces, thus creating more accurate and predictive models of the host inflammatory response [8] [44].

Q2: What are the most common identifiability issues when fitting HNODEs? The primary identifiability challenge in HNODEs is the compensation effect between the mechanistic parameters and the neural network component [44]. The flexibility of the neural network can make it difficult to uniquely determine the values of the mechanistic parameters, as different combinations of parameter values and network outputs can produce similarly accurate fits to the data. This can lead to non-identifiable parameters, where multiple values explain the data equally well, undermining the model's biological interpretability [44].

Q3: What practical steps can I take to improve parameter identifiability in my HNODE? A robust pipeline for parameter estimation and identifiability analysis involves several key steps [44]:

- Global Exploration: Treat the mechanistic parameters as hyperparameters and use global search methods like Bayesian Optimization to initially explore the parameter space.

- Model Training: Train the full HNODE model using gradient-based methods.

- Identifiability Analysis: After training, perform a practical identifiability analysis (e.g., profile likelihood) to determine which parameters are uniquely identified by the data.

- Uncertainty Quantification: For identifiable parameters, calculate confidence intervals to assess estimation uncertainty.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My HNODE training is unstable, and the loss does not converge. What could be wrong? This is a common issue, often stemming from the combination of ODE solvers and gradient-based optimization.