Standardizing Macrophage Polarization: From Foundational Concepts to Reproducible Protocols Across Models

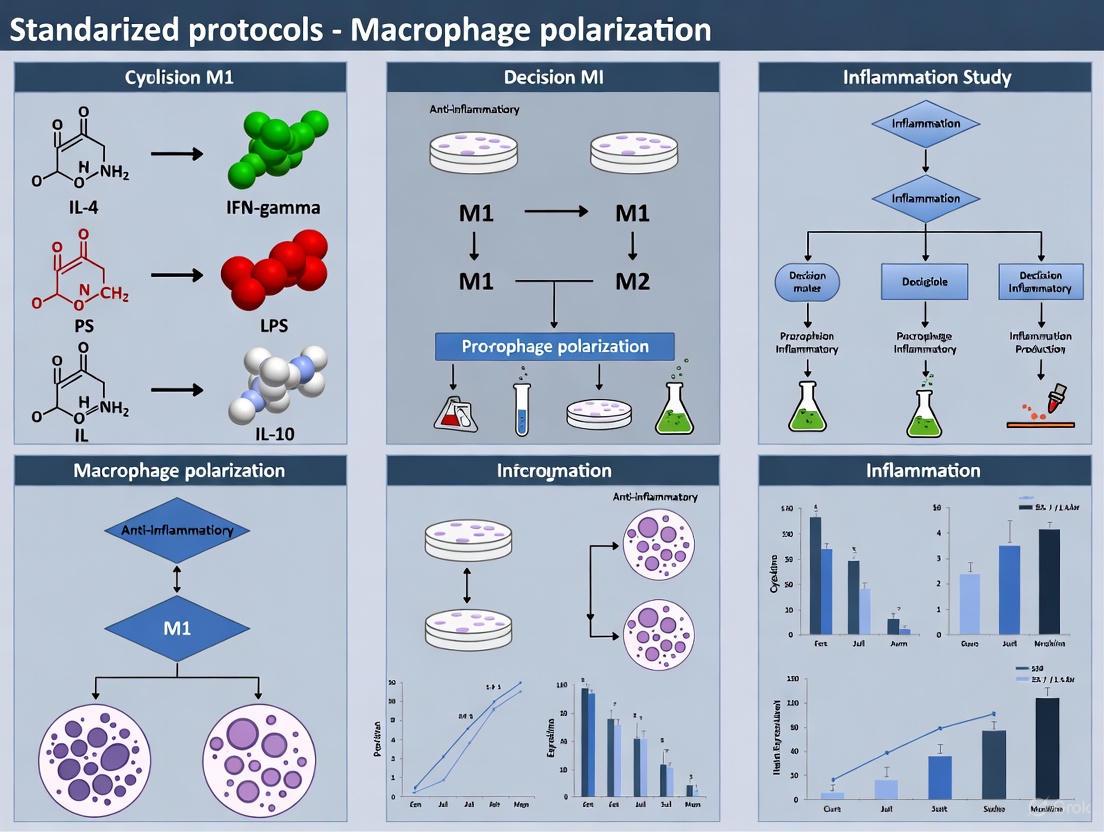

This article provides a comprehensive framework for standardizing macrophage polarization protocols, addressing a critical need in biomedical research.

Standardizing Macrophage Polarization: From Foundational Concepts to Reproducible Protocols Across Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for standardizing macrophage polarization protocols, addressing a critical need in biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current knowledge from foundational principles to advanced applications. We explore the historical context and molecular basis of macrophage polarization, critically evaluate and compare established protocols across primary cells and immortalized lines, address common challenges and optimization strategies, and discuss validation techniques and emerging technologies. By integrating insights from recent studies and established guidelines, this work aims to enhance experimental reproducibility, improve translational relevance, and foster the development of robust, standardized practices in macrophage research.

Deconstructing Macrophage Polarization: From Historical Nomenclature to Modern Molecular Insights

Historical Context and Nomenclature Evolution

The terminology surrounding macrophage activation has undergone significant evolution, leading to both conceptual advances and considerable confusion within the field of immunology. This section traces the historical development of key concepts and the emergence of the nomenclature standards essential for contemporary research.

Key Milestones in Macrophage Activation Terminology

Table: Historical Evolution of Macrophage Activation Terminology

| Time Period | Key Terminology | Defining Stimuli/Criteria | Major Contributors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1990s | Classical vs. Alternative Activation | IFN-γ vs. IL-4 | Gordon, Nathan |

| 2000 | M1 vs. M2 Dichotomy | Th1 vs. Th2 responses; arginine metabolism | Mills |

| Mid-2000s | Subdivision of M2 (M2a, M2b, M2c) | IL-4/IL-13; Immune complexes; IL-10/glucocorticoids | Mantovani |

| 2014 | Consensus Nomenclature (M(Stimulus)) | Standardized reporting of activator and source | International Consensus |

The earliest distinction emerged in the early 1990s, when effects of IL-4 on macrophage gene expression were described as "alternative activation," compared to the effects of IFN-γ, which was termed "classical activation" [1]. The term 'classical' activation originally referred specifically to macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ, but it is now often used interchangeably for macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ and/or TLR agonists like LPS [1].

In 2000, the M1-M2 terminology was introduced by Mills et al., originating from observed differences in arginine metabolism between macrophages from C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice [1]. This was correlated with differences between Th1 and Th2 cell responses in the same strains [1]. The M1/M2 nomenclature was thus born from an observed innate propensity of macrophages from different mouse strains to polarize towards pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory/pro-repair (M2) phenotypes [2] [3].

Subsequent work expanded the M2 category into subdivisions (M2a, M2b, M2c) based on different activation stimuli and functional outputs [3] [4]. However, the proliferation of terminology led to significant confusion, with inconsistent use of markers and definitions across laboratories [1]. This culminated in a 2014 consensus paper that proposed a unified framework for macrophage activation nomenclature, recommending a system where the stimulus is specified in parentheses (e.g., M(IL-4), M(LPS)) to avoid the oversimplified M1/M2 dichotomy and provide greater experimental clarity [1].

Current Standardized Nomenclature and Protocols

Consensus Guidelines for Macrophage Activation Nomenclature

To address the confusion and inconsistency in the field, a consensus of macrophage biologists proposed standardized nomenclature and experimental guidelines. A primary recommendation was to adopt a stimulation-based nomenclature system where macrophages are defined by their specific activator, such as M(IL-4), M(IFN-γ), M(LPS), M(Ig), M(IL-10), and M(GC) for glucocorticoids [1]. This system avoids the complexity and inconsistency of the M2a, M2b, etc. classifications and allows new activation conditions to be compared with core references [1].

The consensus also emphasized that macrophage activation exists on a spectrum rather than in discrete bins, acknowledging the continuum of activation states that macrophages can adopt in response to diverse environmental cues [1]. This concept is particularly valuable when studying macrophages in complex in vivo settings where they are exposed to multiple simultaneous signals.

The standards recommend using CSF-1 cultured macrophages from murine bone marrow and peripheral blood monocytes from humans as the predominant reference systems for in vitro studies [1]. For the paradigmatic in vitro polarized populations, this involves post-differentiation stimulation with IFN-γ for M(IFN-γ) or IL-4 for M(IL-4) populations [1].

Essential Reporting Standards for Reproducibility

Table: Minimal Reporting Standards for Macrophage Polarization Experiments

| Category | Essential Information to Report | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Macrophage Source | Species, tissue origin, isolation method | Human PBMCs, mouse bone marrow |

| Differentiation | Growth factor, concentration, duration | 25 ng/mL CSF-1 for 6 days [5] |

| Polarization | Stimulus, concentration, duration | 20 ng/mL IL-4 for 48 hours [5] |

| Key Markers | Representative surface, genetic, functional markers | CD206, ARG1 for M(IL-4) [5] |

A critical recommendation is to use purified, endotoxin-free recombinant CSF-1 rather than L cell-conditioned media to generate bone marrow-derived macrophages, as the latter is not readily defined and can vary between batches [1]. Furthermore, researchers are encouraged to use macrophages from mice with specific targeted mutations (e.g., IL-4Rα–/– or STAT6-deficient) to confirm specific polarization phenotypes [1].

The consensus also advises avoiding the term "regulatory" macrophages, as all macrophages are regulatory in some capacity, and this term does not provide specific mechanistic information [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do surface markers identified on in vitro generated macrophages often fail to translate to in vivo settings?

A1: This is a fundamental and common issue. Transcriptomic analyses have revealed that although there is some overlap between in vivo M1(=LPS+) and in vitro classically activated (LPS+IFN-γ) macrophages, many more genes are regulated in opposite or unrelated ways [2]. The same is true for in vivo M2(=LPS–) and in vitro alternatively activated (IL-4) macrophages [2]. This explains why many surface markers identified in reductionist in vitro systems do not reliably identify macrophage subsets in complex in vivo environments. Valid universal in vivo M1/M2 surface markers remain to be discovered [2].

Q2: My M(IL-4) macrophages are not expressing expected M2 markers. What could be wrong?

A2: Several factors in your protocol could affect polarization:

- Verify the concentration and activity of your recombinant IL-4. Typical concentrations range from 10-20 ng/mL for 24-48 hours [2] [5].

- Check the purity and differentiation state of your starting population. Ensure monocytes or bone marrow precursors are fully differentiated into macrophages using CSF-1 (e.g., 25 ng/mL for 6 days) before applying polarizing cytokines [5].

- Consider genetic background effects, especially in mouse models. The original M1/M2 dichotomy was described in specific mouse strains (C57BL/6 vs. Balb/c) with known genetic differences in arginine metabolism [1].

- Confirm polarization with multiple markers, not just one. For human M(IL-4) macrophages, expect upregulation of CD206 and CD163, and increased expression of genes like ARG1 and CCL17 [3] [5].

Q3: What is the critical difference between "classical/alternative activation" and "M1/M2" polarization?

A3: The terms have distinct historical origins and are not perfectly synonymous.

- Classical/Alternative Activation: These terms describe specific functional states induced by defined stimuli—IFN-γ for classical and IL-4/IL-13 for alternative activation [1] [3].

- M1/M2 Polarization: This nomenclature originated from the observation that macrophages from different mouse strains had an innate propensity to favor Th1-type (M1) or Th2-type (M2) responses, based on arginine metabolism [1] [3]. While now often used interchangeably, it is crucial to understand this conceptual difference. The consensus nomenclature (M(Stimulus)) helps resolve this confusion by directly reporting the experimental conditions [1].

Q4: How do I properly validate the polarization state of my macrophages?

A4: Employ a multi-parameter validation strategy:

- Gene Expression: Use RT-qPCR to measure hallmark genes. For human M(IFN-γ+LPS): IL12A, NOS2, TNFA. For M(IL-4): ARG1, IL10, MRC1 (CD206) [5].

- Surface Markers: Use flow cytometry. M(IFN-γ+LPS) typically show high CD80/CD86; M(IL-4) show high CD206/CD163 [5].

- Cytokine Secretion: Measure cytokine production in supernatants. M(IFN-γ+LPS) secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12. M(IL-4) secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β [3] [4].

- Functional Assays: Assess metabolic activity (e.g., nitric oxide production for M(IFN-γ+LPS)) or phagocytic capability [3].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

Core Signaling Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

The binary M1/M2 macrophage polarization is governed by distinct signaling pathways and transcriptional networks. The diagrams below illustrate the key signaling cascades involved in these polarization states.

Diagram Title: M1 Macrophage Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: M2 Macrophage Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Macrophage Polarization Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | CSF-1 (M-CSF), GM-CSF | Differentiation from precursors | Use purified, endotoxin-free; GM-CSF primes pro-inflammatory state [1] [2] |

| M1 Polarizers | IFN-γ, LPS (TLR4 agonist) | Induce M(IFN-γ) and M(LPS) phenotypes | Often used in combination for classical activation [3] [5] |

| M2 Polarizers | IL-4, IL-13 | Induce M(IL-4) phenotype | Primary drivers of alternative activation [1] [3] |

| Validation Markers | CD80/CD86 (M1), CD206/CD163 (M2) | Surface marker validation by flow cytometry | Not always translatable to in vivo [2] [5] |

| Genetic Markers | NOS2, IL12 (M1); ARG1, YM1 (M2) | Transcriptional validation by RT-qPCR | Mouse-specific: Chi3l3 (Ym1) [2] [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophage Polarization

This protocol outlines the standardized methodology for generating and polarizing human macrophages from peripheral blood monocytes, a common experimental system [5].

Isolation and Differentiation:

- Isolate human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from buffy coats using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Lympholyte-H).

- Isolate monocytes by positive selection using magnetic beads conjugated with anti-human CD14.

- Culture monocytes for 6 days in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5% human serum, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamine, and 25 ng/mL CSF-1 (M-CSF) to differentiate them into non-polarized (Mφ) macrophages.

Polarization:

- For M(IFN-γ+LPS) polarization: Supplement differentiated macrophages with IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) and LPS from E. coli (100 ng/mL) for 48 hours [5].

- For M(IL-4) polarization: Supplement differentiated macrophages with IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 48 hours [5].

Validation:

- Confirm polarization by flow cytometry for surface markers (CD80/CD86 for M(IFN-γ+LPS); CD206/CD163 for M(IL-4)).

- Validate by RT-qPCR for gene expression markers (IL12A, NOS2 for M(IFN-γ+LPS); ARG1, MRC1 for M(IL-4)) [5].

Advanced Consideration: The Spectrum of M2 Subtypes

Beyond the standard M(IL-4) model, the M2 category encompasses a spectrum of functionally distinct subtypes induced by different stimuli [4]:

- M2a: Induced by IL-4 or IL-13. Key roles in debris clearance, tissue repair, and fibrosis. Produce pro-fibrotic factors (IGF, TGF-β) and chemokines (CCL-17, CCL-18, CCL-22) [4].

- M2b: Induced by immune complexes combined with LPS or IL-1β. Regulatory phenotype releasing both pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines [4].

- M2c: Induced by IL-10, TGF-β, or glucocorticoids. Strongly immunosuppressive, releasing IL-10, TGF-β, CCL-16, and CCL-18 [4].

- M2d: Induced by adenosine A2A receptor engagement. Associated with tumor progression, releasing IL-10, VEGF, and TNF-α [4].

This refined understanding highlights the limitations of a simple M1/M2 binary and underscores the importance of precisely defining experimental conditions using the consensus M(Stimulus) nomenclature.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary markers and secretory profiles that distinguish M1 from M2 macrophages in both human and mouse models? The polarization of macrophages into M1 (classically activated) and M2 (alternatively activated) phenotypes is characterized by distinct markers and secretory profiles, though careful attention to model-specific differences is required for accurate identification [3] [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristic Markers and Secretory Profiles of Macrophage Polarization

| Feature | M1 Macrophages | M2 Macrophages |

|---|---|---|

| Inducing Stimuli | IFN-γ, LPS [3] [6] | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, Glucocorticoids [3] |

| Cell Surface Markers | CD40, CD80, CD86, MHC-IIR [6] | CD163, CD204, CD206 (Mrc1) [3] [6] |

| Secreted Cytokines & Effectors | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, iNOS (NOS2), CXCL10 [3] [6] | IL-10, TGF-β, IGF-1, VEGF, EGF, PDGF, Arg1, Ym1 (Chi3l3), Fizz1 (Retnla), CCL17 [3] [6] |

| Primary Functions | Pro-inflammatory, host defense against pathogens and tumors [6] | Immunoregulation, tissue repair, wound healing, angiogenesis, pro-fibrotic [3] [6] |

Q2: My M2 polarization is inconsistent. What are the critical checkpoints for STAT6 and PPARγ signaling? Inconsistent M2 polarization often stems from suboptimal activation of the IL-4/IL-13/STAT6 and PPARγ signaling axes. Key checkpoints to verify are [3]:

- STAT6 Activation: Ensure IL-4 or IL-13 is binding to the IL-4Rα receptor, triggering JAK1/JAK3-mediated phosphorylation of STAT6. Verify nuclear translocation of phosphorylated STAT6 using immunocytochemistry or western blot.

- Downstream Gene Expression: Confirm upregulation of classic M2 markers like Arg1, Mrc1 (CD206), and Retnla (Fizz1) via qPCR. These are directly controlled by STAT6 and its co-factors IRF4 and PPARγ [3].

- PPARγ Involvement: The transcription factor PPARγ can be activated by fatty acids and works in concert with STAT6. Its activity is crucial for a robust M2 phenotype [3] [7].

Q3: How do non-coding RNAs, particularly miRNAs, influence macrophage phenotype, and can they be targeted? Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), are pivotal post-transcriptional regulators of macrophage polarization. They function as a sophisticated network [7]:

- Mechanism: miRNAs typically suppress gene expression by binding to the 3'-UTR of target mRNAs. Conversely, lncRNAs and circRNAs can act as "sponges" for miRNAs, protecting target mRNAs from repression [7].

- Role in Phenotype Control: Specific ncRNAs have been strongly validated to target and regulate the PPAR signaling pathway, which is a central player in the etiology of conditions like metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and is crucial for M2 polarization [7]. A study identified 127 ncRNAs in MAFLD, 25 of which were strongly validated for regulating PPARs [7].

- Therapeutic Targeting: Targeting these ncRNAs presents a novel approach for therapeutic strategies. For instance, manipulating ncRNAs that control the PPARγ molecular mechanism can influence metabolic disease and associated macrophage-driven inflammation [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or No M1 Polarization Response to IFN-γ and LPS Inadequate M1 activation can halt pro-inflammatory experiments.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low M1 Polarization

| Problem Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Parameters to Verify |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or Inefficient Stimuli | Use fresh, high-purity LPS (e.g., from E. coli O111:B4) and bioactive IFN-γ. Titrate concentrations (common range: 10-100 ng/mL LPS, 10-50 ng/mL IFN-γ). | Check endotoxin levels and cytokine activity. |

| Impaired NF-κB / MAPK Signaling | Verify TLR4 functionality. Use a positive control like a known NF-κB activator. Inhibit potential negative regulators (e.g., check for SOCS1 overexpression). | Phospho-p65 (NF-κB) and phospho-p38/MAPK via western blot. |

| Insufficient STAT1 Activation | Ensure IFN-γ receptor is not blocked or downregulated. Check STAT1 phosphorylation (Tyr701) and nuclear translocation. | Flow cytometry or western blot for p-STAT1. |

| Incorrect Cell Type/State | Use primary macrophages (e.g., BMDMs, PBMCs-derived) where possible. Cell lines may be refractory. Confirm baseline health and absence of M2-skewing media components (e.g., M-CSF excess). | Cell viability and baseline marker expression. |

Problem: Excessive Inflammatory Response in M2-Conditioned Macrophages Contamination of M2 cultures with M1 features indicates failed polarization.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Contaminated M2 Polarization

| Problem Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Parameters to Verify |

|---|---|---|

| Endotoxin/LPS Contamination | Use certified endotoxin-free reagents (IL-4, IL-13, serum, media). Filter-sterilize all solutions. | Test culture media and reagents for endotoxin (<0.1 EU/mL). |

| Insufficient Polarizing Signal | Increase concentration of IL-4/IL-13 (common range: 10-50 ng/mL). Pre-treat serum to remove potential inhibitory factors. Refresh polarizing cytokines every 2 days for long cultures. | Dose-response for Arg1 or Mrc1 mRNA expression. |

| Interferon Gamma Contamination | Strictly separate cell culture spaces and equipment for M1 and M2 work. Use dedicated media and consumables. | Screen for M1 markers (e.g., NOS2, TNF-α) via qPCR. |

| Inherent Pro-inflammatory Milieu | For ex vivo cells, ensure the donor/animal model is not in a systemic inflammatory state. Allow cells to rest post-isolation before polarization. | Baseline cytokine levels in cell culture supernatant. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

STAT3 Signaling in Macrophage Polarization

STAT3 is a critical transcription factor involved in regulating the balance of macrophage polarization, influencing both pro-tumor and anti-inflammatory functions [6]. Its activation is tightly regulated by phosphorylation at tyrosine 705 (Y705) and serine 727 (S727), leading to dimerization, nuclear translocation, and transcription of target genes [6]. The diagram below illustrates the core STAT3 signaling pathway and its crosstalk with other polarization signals.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Macrophage Polarization Status

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for polarizing macrophages and confirming their phenotype through gene expression analysis [3] [6].

1. Macrophage Differentiation and Polarization:

- Isolation and Differentiation: Isolate primary monocytes from human PBMCs or mouse bone marrow. Differentiate into naive macrophages (M0) by culturing in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and either 50 ng/mL human M-CSF (for human) or 20 ng/mL mouse M-CSF (for mouse) for 5-7 days.

- Polarization Stimulation:

- M1 Polarization: Stimulate M0 macrophages for 24-48 hours with 20-100 ng/mL IFN-γ followed by, or concurrently with, 10-100 ng/mL ultrapure LPS.

- M2 Polarization: Stimulate M0 macrophages for 48-72 hours with 20-50 ng/mL IL-4 and/or IL-13. Refresh cytokines every 2 days for longer cultures.

2. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis:

- RNA Extraction: Lyse polarized macrophages in TRIzol reagent and extract total RNA following the manufacturer's protocol. Determine RNA concentration and purity by spectrophotometry.

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 1 µg of total RNA into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit with random hexamers.

- qPCR: Perform qPCR reactions in triplicate using SYBR Green master mix and gene-specific primers. Use the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method to calculate relative gene expression, normalized to a housekeeping gene (e.g., Actb or Gapdh).

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Macrophage Polarization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Target/Analyte |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13, M-CSF) | Induce and sustain macrophage differentiation and polarization. | Cell surface receptors (e.g., IL-4Rα, IFNGR). |

| Ultra-Pure LPS | A specific TLR4 agonist for classical M1 activation. | TLR4, NF-κB pathway. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (Flow Cytometry/Western Blot) | Detect activation of key signaling pathways. | p-STAT1 (Y701), p-STAT6 (Y641), p-p65 (NF-κB). |

| ELISA Kits | Quantify secreted cytokines in supernatant to confirm functional polarization. | TNF-α, IL-12 (M1); IL-10, TGF-β (M2). |

| qPCR Primers | Measure mRNA expression of polarization-specific markers. | NOS2, TNF-α (M1); Arg1, Mrc1, Fizz1 (M2). |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Antibodies (Flow Cytometry) | Identify and sort macrophage populations based on surface markers. | CD80, CD86 (M1); CD206, CD163 (M2). |

3. Functional Validation (Optional):

- Phagocytosis Assay: Use pHrodo Bioparticles to assess the phagocytic capacity of polarized macrophages. M2 macrophages often exhibit higher phagocytic activity.

- Nitric Oxide Production: Measure nitrite accumulation in culture supernatants using the Griess reagent as an indicator of M1-associated iNOS activity (more relevant in mouse models).

Core Concepts: Metabolic Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

What are the fundamental metabolic differences between M1 and M2 macrophages?

Macrophage polarization is coupled to distinct metabolic programs. M1 macrophages (pro-inflammatory), activated by stimuli like LPS and IFN-γ, primarily rely on aerobic glycolysis for rapid energy production, even in the presence of oxygen. In contrast, M2 macrophages (anti-inflammatory), activated by IL-4 or IL-10, are more dependent on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to fuel their longer-term functions [8] [9].

The table below summarizes the key metabolic characteristics of these polarized states.

Table 1: Core Metabolic Profiles of M1 and M2 Macrophages

| Metabolic Feature | M1 Macrophages | M2 Macrophages |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Pathway | Aerobic Glycolysis [10] [9] | Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [8] [9] |

| TCA Cycle | Broken or interrupted; accumulation of intermediates like succinate [8] [9] | Intact and functional [8] |

| Arginine Metabolism | iNOS pathway → Nitric Oxide (NO) and citrulline [11] [8] | Arginase-1 pathway → Ornithine and urea [8] [9] |

| Fatty Acid Metabolism | Increased fatty acid synthesis (FAS) [8] | Increased fatty acid oxidation (FAO) [9] |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Enhanced [8] [9] | Decreased [8] |

| Key Transcription Factors | HIF-1α, mTORC1 [11] | PPARs, PGC-1β, AMPK [11] [9] |

Experimental Protocols: Polarizing and Assessing Macrophages

What is a standardized protocol for differentiating THP-1 cells into M1 and M2 macrophages?

The human monocytic THP-1 cell line is a common model. The following protocol, adapted from the literature, provides a method for generating distinct macrophage phenotypes [12].

- Cell Culture: Maintain THP-1 cells in recommended growth medium.

- Differentiation to M0: Differentiate THP-1 cells into naive macrophages (M0) by treating with 100 ng/mL Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24-48 hours.

- Polarization:

- Rest Period: After PMA treatment, a rest period in fresh medium without PMA is recommended before polarization to minimize the effects of PMA and allow the cells to mature [12].

How can I confirm successful polarization and metabolic reprogramming?

Polarization can be validated by assessing classic surface markers and gene expression. Metabolically, you can measure the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as a proxy for glycolysis and the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) as a proxy for OXPHOS.

Table 2: Key Markers for Validating Macrophage Polarization

| Macrophage Phenotype | Surface & Genotypic Markers | Key Metabolic Enzymes & Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | CD80, CD86, iNOS [11] | High HIF-1α, PKM2, GLUT1; High ECAR [11] [8] |

| M2a (IL-4) | CD206, CD200R, MRC1, CCL17 [11] [12] | High Arg1, PPARγ, PGC-1β; High OCR [11] [9] |

| M2c (IL-10) | CD163, C1QA [11] [12] | High Arg1; High OCR [11] |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: My macrophages are not polarizing correctly—the marker expression is weak or inconsistent. What could be wrong?

This is a common challenge. Follow a systematic troubleshooting approach.

Step 1: Identify the Problem

- Clearly define the issue. For example: "The expression of CD206 in my M(IL-4) cells is 50% lower than expected based on literature."

Step 2: List All Possible Explanations [13]

- Cell Health & Source: Low cell viability before polarization, mycoplasma contamination, use of a different monocyte source (e.g., primary vs. THP-1).

- Reagents: Inaccurate cytokine concentrations; degraded or improperly stored cytokines (e.g., repeated freeze-thaw cycles); incorrect antibody validation for staining.

- Protocol Timing: Insufficient or excessive polarization time; no rest period after PMA differentiation for THP-1 cells [12].

- Culture Conditions: Suboptimal serum batch; presence of metabolites in the media that influence polarization.

Step 3: Collect Data & Eliminate Explanations [14]

- Controls: Always include a positive control (e.g., a known M1/M2 inducer that has worked in your lab) and unstained/isotype controls for flow cytometry.

- Reagent Validation: Check cytokine expiration dates and storage conditions. Use a new aliquot to rule out degradation.

- Documentation: Review your lab notebook to ensure no steps were accidentally modified.

Step 4: Check with Experimentation [14]

- Change one variable at a time. For example, test a range of IL-4 concentrations (e.g., 10, 20, 50 ng/mL) or polarization times (24 vs. 48 hours) to optimize the protocol for your specific conditions.

- Use qPCR to check multiple marker genes (e.g., for M2: MRC1, CCL17, ARG1) to get a more robust picture of polarization [12].

FAQ: My metabolic flux data (Seahorse) does not show the expected glycolytic switch in M1 macrophages. How can I troubleshoot this?

Step 1: Verify the Polarization State

- First, confirm via qPCR or flow cytometry that your M1 macrophages are indeed polarized (high TNFα, IL6, iNOS). If polarization is not achieved, metabolic changes will not follow.

Step 2: Interrogate the Assay Conditions

- Cell Preparation: Ensure cells are seeded at the optimal density for the assay plate. Over-confluency can affect metabolic readings.

- Substrate Availability: The assay medium must contain glucose to measure glycolysis. Confirm the composition of your assay medium.

- Inhibitor Potency: Check the concentration and stability of metabolic inhibitors used in the assay (e.g., 2-DG, oligomycin). Prepare fresh stocks if necessary.

Step 3: Consider Metabolic Checkpoints

- HIF-1α Stabilization: The glycolytic switch in M1 macrophages is heavily dependent on HIF-1α, even under normoxia [10]. Ensure your culture conditions and stimuli (LPS) are robust enough to stabilize HIF-1α.

- iNOS/NO Feedback: High NO production from iNOS can inhibit mitochondrial respiration, further pushing metabolism toward glycolysis [8]. Check iNOS expression as a proxy for this process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Macrophage Metabolic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polarization Cytokines | Induces specific macrophage phenotypes. | Recombinant human/mouse IFN-γ (for M1), IL-4 (for M2a), IL-10 (for M2c). Aliquot and store at -80°C to avoid freeze-thaw degradation [12]. |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Tool compounds to probe specific pathways. | 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG): Glycolysis inhibitor [8]. Note: Be aware of potential off-target effects [8]. Oligomycin: ATP synthase inhibitor. |

| Extracellular Flux Assay Kits | Measure OCR and ECAR in live cells. | Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit, Mito Stress Test Kit. Essential for functional metabolic phenotyping. |

| Antibodies for Validation | Confirm polarization status via protein expression. | Anti-iNOS (for M1), Anti-CD206 (for M2a), Anti-CD163 (for M2c). Always validate antibodies for your specific application and species. |

| THP-1 Cell Line | Human monocyte model for in vitro studies. | Requires PMA for differentiation into macrophage-like (M0) state before polarization [12]. |

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Networks

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core signaling pathways and metabolic networks that drive M1 and M2 macrophage polarization.

Diagram 1: Key drivers of M1 macrophage metabolic reprogramming.

Diagram 2: Key drivers of M2 macrophage metabolic reprogramming.

Core Concepts: The Macrophage Functional Spectrum

Why is the traditional M1/M2 classification considered insufficient for describing macrophage states in vivo?

The traditional M1/M2 classification is considered insufficient because it represents an oversimplified framework that fails to capture the true complexity and dynamic nature of macrophages in physiological and pathological environments. While this dichotomy has provided a useful foundational model, contemporary research reveals that macrophage phenotypes in vivo exist along a dynamic continuum rather than falling into discrete categories [15].

Advanced single-cell transcriptomics and spatial multi-omics technologies have fundamentally transformed our understanding of macrophage biology, demonstrating remarkable plasticity shaped by multiple factors: (1) local microenvironmental cues including metabolic signaling and extracellular matrix composition; (2) developmental origins distinguishing tissue-resident from monocyte-derived populations; and (3) disease-specific pathological contexts [15]. This multifaceted regulation network renders conventional binary classification systems biologically inadequate for capturing the full complexity of macrophage functional states.

Recent studies have revealed a paradigm-shifting phenomenon where certain macrophage populations can co-express both classical M1 and M2 markers, demonstrating an unprecedented capacity for rapid functional switching between antimicrobial defense and tissue repair processes [15]. Furthermore, in complex tissue environments, macrophages are constantly exposed to multiple and sometimes conflicting cues, leading to heterogeneous responses at the single-cell level that cannot be adequately described by simple M1/M2 categorization [16].

What technical approaches provide better resolution for characterizing macrophage states?

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing macrophage transcriptomes at single-cell resolution, enabling researchers to identify subsets with unique gene expression patterns that transcend conventional surface marker-based paradigms [15] [16]. This technology allows for the detection of heterogeneous responses within seemingly uniform macrophage populations, particularly when cells are exposed to conflicting polarization signals [16].

The integration of single-cell multi-omics with spatial profiling technologies represents the current gold standard for achieving higher-resolution characterization of macrophage subsets [15]. These approaches enable researchers to establish functionally defined classification frameworks that account for both transcriptional diversity and spatial localization within tissues, providing crucial context for understanding macrophage functions in physiological and disease states.

Machine learning approaches combined with single-cell technologies are also providing new perspectives for decoding macrophage states, suggesting that despite their complexity, macrophage states may represent two fundamental opposing populations: inflammatory macrophages that respond to neutralize threats, and non-inflammatory macrophages that promote healing and maintain homeostasis [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

How can I resolve inconsistent polarization outcomes in my THP-1 differentiation experiments?

Inconsistent polarization of THP-1 cells typically stems from variations in differentiation and polarization protocols. To address this, implement these standardized experimental conditions:

- For M(IFNγ+LPS) phenotype: Use optimized PMA exposure with minimized impact, followed by appropriate rest periods and cytokine exposure [12].

- For M(IL-4) phenotype: Ensure proper polarization to obtain cells that transcriptionally express CCL17, CCL26, CD200R and MRC1 [12].

- For M(IL-10) phenotype: Verify that cells express characteristic markers including CD163, C1QA and SEPP1 [12].

A critical factor is monitoring the balance of activating to inhibitory Fcγ Receptors, as the inhibitory Fcγ Receptor IIb is preferentially expressed on the surface of M(IL-4) cells, providing a useful validation marker for successful polarization [12].

What could explain mixed macrophage phenotypes in my stimulation experiments?

The appearance of mixed phenotypes is likely a genuine biological response, particularly when macrophages are exposed to multiple conflicting environmental cues. Single-cell RNA sequencing studies demonstrate that when co-stimulated with opposing signals (e.g., LPS+IFN-γ and IL-4), individual macrophages exhibit heterogeneous responses, with some genes from each program showing negative cross-regulation [16].

This heterogeneity represents a legitimate functional diversity strategy that macrophages use to respond to complex microenvironmental signals. Rather than technical artifacts, these mixed phenotypes may reflect the sophisticated adaptation of macrophages to conflicting cues in your experimental system. To characterize this properly, employ single-cell resolution approaches that can capture the full spectrum of cellular responses within your population [16].

Why do I observe different macrophage polarization patterns across disease models?

Differential polarization patterns across disease models reflect the context-dependent nature of macrophage programming. Different pathological environments create distinct cytokine and signaling milieus that drive disease-specific polarization states:

- In osteoarthritis, synovial macrophages exhibit polarization states that contribute to persistent low-grade inflammation, synovial membrane remodeling, and cartilage breakdown [18].

- In Crohn's disease, intestinal inflammation features a dominant population of IFNγ-polarized macrophages with concurrent loss of wound healing IL-4-, IL-10- and IL-13-polarized macrophages [19].

- In rheumatoid arthritis, synovial tissue and peripheral blood show high expression of M1-like macrophages producing TNF-α, IL-6, and other inflammatory cytokines that perpetuate disease [20].

- In tumor microenvironments, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) typically polarize toward M2-like phenotypes that promote angiogenesis, immune evasion, and tissue remodeling [15].

These differences highlight the importance of context-specific standardization when developing polarization protocols for particular disease modeling applications.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized THP-1 Differentiation Protocol

Table 1: Optimized cytokine combinations for specific macrophage phenotypes

| Target Phenotype | Stimulating Cytokines | Key Characteristic Markers | Functional Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| M(IFNγ+LPS) | IFN-γ + LPS | CD80, CD86, IL-12, IL-23 | Pro-inflammatory response, pathogen clearance |

| M(IL-4) | IL-4 | CCL17, CCL26, CD200R, MRC1, FcγRIIb | Tissue repair, immunoregulation |

| M(IL-10) | IL-10 | CD163, C1QA, SEPP1 | Anti-inflammatory, immunoregulation |

| Co-stimulated | LPS+IFN-γ + IL-4 | Heterogeneous expression of Il12b/Il6 vs Arg1/Chil3 | Response to conflicting cues [16] |

Signaling Pathway Modulation Approaches

Understanding the key signaling pathways that regulate macrophage polarization enables targeted experimental modulation:

Diagram 1: Key signaling pathways regulating macrophage polarization states and their cross-regulation

Metabolic Reprogramming Methods

Macrophage polarization is intrinsically linked to metabolic reprogramming, which provides both energy and biosynthetic precursors for functional specialization:

Table 2: Metabolic programs associated with different macrophage polarization states

| Polarization State | Primary Metabolic Pathway | Key Metabolic Features | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1/Inflammatory | Glycolysis | HIF-1α stabilization, NADPH oxidase activity, Succinate accumulation | Rapid ATP production, ROS generation, pro-inflammatory cytokine production |

| M2/Anti-inflammatory | Oxidative Phosphorylation + Fatty Acid Oxidation | PPARγ/LXR signaling, Mitochondrial biogenesis | Efficient energy production, anti-inflammatory cytokine synthesis |

| Tumor-Associated | Context-dependent | Altered amino acid metabolism (e.g., Arg1-mediated arginine depletion) | Immunosuppression, tissue remodeling support |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for macrophage polarization studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polarizing Cytokines | IFN-γ, LPS, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 | Induce specific polarization states | Use validated concentrations: 10-20 ng/mL IFN-γ, 10-100 ng/mL LPS, 20-100 ng/mL IL-4 [12] [16] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | JAK inhibitors, NF-κB inhibitors, PI3K/AKT inhibitors | Pathway-specific modulation of polarization | Validate specificity and assess off-target effects |

| Metabolic Modulators | 2-DG (glycolysis inhibitor), Etomoxir (FAO inhibitor) | Investigate metabolic reprogramming | Confirm target engagement with metabolic assays |

| Cell Lines | THP-1, RAW 264.7 | Reproducible model systems | Implement standardized differentiation protocols [12] |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD80, CD86, CD206, CD163, MHC-II | Phenotype validation via flow cytometry | Use validated antibody clones, include appropriate controls |

| Detection Assays | ELISA for IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α; NO detection | Functional validation of polarization | Establish standard curves with reference standards |

Advanced Experimental Design Considerations

Single-Cell Resolution Workflow

For comprehensive characterization of macrophage states, implement this integrated workflow:

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for comprehensive macrophage state characterization

Data Integration Framework

When interpreting macrophage polarization data, employ a multi-dimensional framework that considers:

- Transcriptional profiles from scRNA-seq data

- Surface marker expression via flow cytometry

- Secretory profiles through cytokine multiplexing

- Metabolic states using metabolic flux assays

- Spatial context via imaging or spatial transcriptomics

This integrated approach ensures comprehensive characterization of macrophage functional states that transcends the limitations of traditional M1/M2 classification and accounts for the complex spectrum of macrophage biology in vivo.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Macrophage Polarization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My M1 macrophages are not producing high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) upon LPS stimulation. What could be wrong?

A: This is a common issue often related to TLR4 signaling. Consider the following:

- Priming Signal Interference: Ensure your IFN-γ priming step is effective. Check the activity and concentration of your IFN-γ reagent.

- LPS Specificity and Potency: Use ultrapure LPS from a reputable supplier to specifically activate TLR4, not other contaminants. Verify the potency and reconstitution of your LPS stock.

- TLR4 Expression: Confirm TLR4 receptor expression on your macrophage cell line or primary cells via flow cytometry.

- Inhibitory Feedback: Long stimulation times can induce feedback inhibitors like IRAK-M or A20. Perform a time-course experiment (e.g., 2, 6, 12, 24 hours) to identify the peak cytokine production window.

Q2: I am trying to polarize towards an M2 phenotype, but the cells do not show expected markers (e.g., CD206, Arg1). What should I check?

A: M2 polarization failure often stems from issues with the PI3K-AKT pathway or the polarizing agents.

- IL-4/IL-13 Activity: Verify the bioactivity of your IL-4 and/or IL-13. These cytokines are labile; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Serum Batches: Different batches of FBS can have varying levels of endogenous cytokines and growth factors that skew polarization. Use the same validated batch for an entire study or consider using serum-free macrophage media.

- PI3K-AKT Pathway Blockade: The M2 phenotype is PI3K-AKT dependent. If using inhibitors for other pathways, ensure they are not non-specifically inhibiting PI3K. You can check AKT phosphorylation (p-AKT Ser473) as a readout of pathway activity.

Q3: My metabolic assays (e.g., Seahorse) show inconsistent results between M1 and M2 populations. Why is the expected glycolytic shift in M1 macrophages not occurring?

A: The AMPK pathway is a master regulator of metabolism, and its activity can be influenced by many factors.

- Cell Preparation State: Ensure cells are in a consistent metabolic state before assay. Avoid over-confluency and nutrient exhaustion in the culture media prior to the assay.

- AMPK Activators/Inhibitors: Check for unintended AMPK activators (e.g., Metformin contamination, high AMP/ATP ratio from stress) or inhibitors in your media or reagents.

- Assay Timing: The metabolic shift is dynamic. For M1, the glycolytic burst may peak 6-12 hours after LPS stimulation. Ensure your assay timing aligns with the peak of metabolic reprogramming.

Q4: I observe a mixed phenotype with co-expression of M1 and M2 markers. Is this expected?

A: While simplified models depict pure M1 or M2 states, macrophages exist on a spectrum. However, significant mixing in controlled in vitro settings suggests:

- Incomplete Polarization: The polarizing signal may be insufficient or not long enough. Optimize cytokine concentration and duration.

- Contaminating Stimuli: The culture might be contaminated with low levels of endotoxin (LPS), which can dominate over an M2 signal. Use sterile, endotoxin-free techniques and reagents.

- Plasticity: The cells may be transitioning. Consider a "resting" period in neutral media after polarization before analysis to stabilize the phenotype.

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Viability Post-Polarization | Cytokine toxicity (high-dose IFN-γ/LPS), excessive inhibitor concentration. | Titrate cytokines and pharmacological agents. Perform a viability assay (e.g., MTT, live/dead staining) 24h after polarization induction. |

| High Background Inflammatory Markers in M0/M2 | Endotoxin contamination in media/FBS, inappropriate cell source (e.g., monocyte isolation from inflamed donor). | Use certified endotoxin-free reagents and serum. Implement an endotoxin removal step for critical reagents. Isolate monocytes from healthy donors. |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Experiments | Inconsistent cell seeding density, operator variability in media changes, different reagent lots. | Standardize all protocols: cell counting method, seeding density, media change volumes/timing. Use large, aliquoted batches of key reagents. |

| Weak Signal in Western Blot for p-IκBα, p-AKT, p-AMPK | Inefficient cell lysis, rapid dephosphorylation, suboptimal antibody. | Use fresh, hot Laemmli buffer for direct lysis. Include phosphatase inhibitors in lysis buffer. Harvest cells quickly post-stimulation. Validate antibodies. |

Table 1: Characteristic Signaling Events and Outputs in Macrophage Polarization

| Pathway | Key Stimulus | Key Phosphorylation Event (Readout) | Characteristic Gene/Marker Output | Primary Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4/NF-κB | LPS (100 ng/mL) | IκBα degradation, p65 nuclear translocation | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, iNOS | M1 (Pro-inflammatory) |

| PI3K-AKT | IL-4 (20 ng/mL) | AKT (Ser473) phosphorylation | Arg1, CD206, Ym1/2, CCL17 | M2 (Anti-inflammatory) |

| AMPK | Metabolic stress (e.g., low glucose) | AMPKα (Thr172) phosphorylation | PGC-1α, FAO enzymes, ↑ Mitochondrial biogenesis | M2 (Oxidative Metabolism) |

Table 2: Common Pharmacological Modulators for Pathway Validation

| Target Pathway | Activator (Example) | Inhibitor (Example) | Use in Polarization Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4/NF-κB | Ultrapure LPS (100 ng/mL) | TAK-242 (1 µM) | Induce or block M1 polarization. |

| PI3K-AKT | IGF-1 (50 ng/mL) | LY294002 (10 µM) | Enhance or block M2 polarization. |

| AMPK | AICAR (1 mM), Metformin (2 mM) | Compound C (10 µM) | Drive or inhibit M2-associated oxidative metabolism. |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Validation

Protocol 1: Validating M1 Polarization via TLR4/NF-κB Signaling (Western Blot)

- Cell Preparation: Seed macrophages (e.g., RAW 264.7, primary BMDMs) in 6-well plates at 0.5-1.0 x 10^6 cells/well. Culture overnight.

- Stimulation: Stimulate cells with IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) for 3-6 hours for priming, followed by Ultrapure LPS (100 ng/mL) for 15-30 minutes. Include an inhibitor control (e.g., TAK-242, 1 µM, pre-incubated 1 hour before LPS).

- Cell Lysis: Aspirate media and lyse cells directly in 150 µL of hot 1X Laemmli buffer supplemented with 1x protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Scrape and collect lysates.

- Analysis: Boil samples for 10 minutes, run SDS-PAGE, and transfer to PVDF membrane. Probe for p-IκBα (Ser32/36), total IκBα, and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH). Degradation of IκBα indicates pathway activation.

Protocol 2: Assessing M2 Polarization via PI3K-AKT Signaling (Flow Cytometry)

- Polarization: Polarize macrophages with IL-4 (20 ng/mL) and IL-13 (20 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours.

- Intracellular Staining for p-AKT: After polarization, harvest and fix cells with 4% PFA for 10 min at 37°C. Permeabilize with cold 90% methanol on ice for 30 min.

- Staining: Wash cells and stain with an antibody against p-AKT (Ser473) for 1 hour at room temperature. Use an Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Analysis: Analyze by flow cytometry. A rightward shift in fluorescence intensity in the IL-4/IL-13 treated sample compared to the M0 control indicates AKT activation.

Protocol 3: Measuring Metabolic Shift via AMPK (Seahorse XF Analyzer)

- Polarization: Polarize macrophages to M1 (LPS 100 ng/mL + IFN-γ 20 ng/mL) or M2 (IL-4 20 ng/mL) for 12-18 hours.

- Seahorse Assay Setup: Seed polarized cells into a Seahorse XF96 cell culture microplate one day before the assay. On the day of the assay, replace media with XF base medium supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM L-glutamine. Incubate at 37°C, CO2-free for 1 hour.

- Mitochondrial Stress Test: Inject ports with: Port A - Oligomycin (1.5 µM), Port B - FCCP (1 µM), Port C - Rotenone/Antimycin A (0.5 µM).

- Analysis: Calculate key parameters: Glycolysis (from extracellular acidification rate, ECAR) and Oxidative Phosphorylation (from oxygen consumption rate, OCR). Expect M1 to have higher ECAR and M2 to have higher OCR.

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

TLR4/NF-κB Signaling in M1 Polarization

PI3K-AKT Signaling in M2 Polarization

AMPK Metabolic Regulation in Macrophages"

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function & Role in Polarization | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure LPS | Specific TLR4 agonist to induce canonical M1 polarization via NF-κB. | InvivoGen tlrl-3pelps |

| Recombinant Murine IFN-γ | Priming cytokine for M1 polarization; enhances TLR4 signaling and MHC II expression. | PeproTech 315-05 |

| Recombinant Murine IL-4 | Primary cytokine for inducing alternative M2a polarization via PI3K-AKT. | PeproTech 214-14 |

| TAK-242 (Resatorvid) | Small molecule inhibitor of TLR4 signaling; used to confirm TLR4-specific effects. | MedChemExpress HY-11109 |

| LY294002 | Potent and specific PI3K inhibitor; used to block M2 polarization. | Cayman Chemical 70920 |

| AICAR | AMPK activator; used to drive M2-like metabolic programming. | Tocris Bioscience 2840 |

| Anti-CD206 (MMR) Antibody | Cell surface marker for M2 macrophages; used for validation by flow cytometry. | BioLegend 141706 |

| Anti-iNOS Antibody | Intracellular marker for M1 macrophages; used for validation by WB/IF. | Cell Signaling Technology 2982 |

Protocol Standardization Across Models: From THP-1 Cells to Primary Human Macrophages

Macrophages are phagocytic innate immune cells that maintain homeostasis by interacting with various tissues, modulating immunological responses, and secreting cytokines [21]. In vitro macrophage cultivation is a crucial biological technique for mimicking different disease microenvironments, primarily relying on two distinct model types: primary macrophage models and immortalized macrophage models [21]. Primary macrophages, which are directly isolated from organisms without genetic alteration or immortalization, maintain biological activity and population characteristics closer to in vivo physiological states [21] [22]. This technical support center focuses on three primary macrophage models—Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs), Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC)-derived macrophages, and tissue-resident macrophages—to provide standardized protocols and troubleshooting guidance for researchers working on macrophage polarization within the context of protocol standardization across models.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Primary Macrophage Models

| Model Type | Developmental Origin | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMDMs | Bone marrow monocytes (BMMs) | High physiological relevance, pronounced polarization plasticity, strong phagocytic capability [21] [22] | Technically challenging isolation, requires 5-7 day induction [21] [22] | Metabolic studies, genetic knockout validation, polarization studies [21] [22] |

| PBMC-Derived | Peripheral blood monocytes | Closer to human physiology, can reflect donor health status [21] | Diverse genetic backgrounds, significant individual differences [23] | Human-specific immune responses, translational research [21] |

| Tissue-Resident | Embryonic origin (self-renewing) or bone marrow-derived monocytes [21] | Maintain tissue-specific functions, represent authentic microenvironment [21] | Extremely difficult to isolate, low yield, cannot be passaged [21] | Tissue-specific pathophysiology, developmental studies [21] |

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Methodologies

BMDM Isolation and Differentiation Protocol

Animal-Derived BMDMs (Mouse) BMDMs are isolated from mouse femurs and tibias using a standard bone marrow harvest and erythrocyte lysis protocol [21] [22]. The isolation and differentiation process requires meticulous technique:

- Bone Marrow Harvest: Flush marrow cavities of femurs and tibias with cold PBS using a sterile syringe and needle [21].

- Erythrocyte Lysis: Use ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysing buffer to remove red blood cells [21].

- Differentiation Culture: Seed cells in media containing Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) or equivalent factors (e.g., secretory factors from L929 cells) [21] [22].

- Maturation Timeline: Mature BMDMs are obtained after a 5-7 day induction period [21] [22].

Critical Note: The morphology of BMDMs is significantly influenced by polarization status. Stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ (M1-polarizing) leads to flattened pancake-like morphology within 24 hours, whereas elongated cellular shape is promoted by IL-4 and IL-13 (M2-polarizing) [21] [22].

PBMC-Derived Macrophage Differentiation

PBMCs represent a mixed population including stem cells (0.1-0.2%), natural killer cells (5-10%), dendritic cells (1-2%), T lymphocytes (70-90%), and monocytes (10-30%) [21] [22]. The isolation and differentiation protocol:

- PBMC Isolation: Isolate PBMCs from human peripheral blood using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque) [21].

- Monocyte Enrichment: Use adherence selection, magnetic bead sorting (CD14+), or flow cytometry sorting to isolate monocytes from the PBMC mixture [21].

- Macrophage Differentiation: Culture monocytes with M-CSF (typically 50 ng/mL) for 5-7 days to differentiate into macrophages [22].

Macrophage Polarization Protocols

M1 Polarization (Classical Activation)

- Stimuli: Microbial products (e.g., LPS) or pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ) [3].

- Standard Protocol: Stimulate differentiated macrophages with 50 ng/mL IFN-γ combined with 15-100 ng/mL LPS for 24-48 hours [23] [3].

- Key Signaling Pathways: IFN-γ activates the JAK1/2-STAT1 pathway, while LPS binding to TLR4 activates both MyD88/NF-κB and TRIF/IRF3 pathways [3] [24].

M2 Polarization (Alternative Activation)

- M2a Subtype: Stimulate with IL-4 (20-25 ng/mL) alone or combined with IL-13 (25 ng/mL) for 48-72 hours [23].

- M2b Subtype: Stimulate with LPS (100 ng/mL) plus immune complexes for 24 hours [23].

- M2c Subtype: Stimulate with IL-10 (10 ng/mL) for 24-72 hours [23].

- Key Signaling Pathways: IL-4 and IL-13 bind to IL-4Rα receptor, activating JAK1/JAK3 and STAT6, which translocates to the nucleus along with IRF4 and PPARγ to modulate M2 gene expression [3].

Diagram 1: Macrophage Polarization Pathways and Subtypes. This diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways and stimuli involved in macrophage polarization from the resting M0 state to various activated phenotypes.

Troubleshooting Guides: Frequently Encountered Experimental Challenges

Polarization Efficiency Issues

Problem: Incomplete or Inconsistent M1 Polarization

- Potential Cause: Inadequate stimulation strength or duration.

- Solution: Optimize cytokine concentrations (IFN-γ: 50 ng/mL; LPS: 15-100 ng/mL) and ensure sufficient exposure time (24-48 hours) [23]. Verify LPS activity and use fresh aliquots to avoid degradation.

- Validation Method: Measure characteristic M1 markers: CD86, CD80, iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, CXCL10 [3] [24].

Problem: Poor M2 Polarization with Inadequate Marker Expression

- Potential Cause: Insufficient IL-4/IL-13 exposure or incorrect PMA priming for THP-1 models.

- Solution: For primary macrophages, use 20-25 ng/mL IL-4 for 48-72 hours [23]. For THP-1 models, ensure appropriate PMA concentration (5-10 ng/mL) as higher concentrations (100 ng/mL) compromise M2 polarization [25].

- Validation Method: Assess characteristic M2 markers: CD206, CD163, Arg1, Ym1, Fizz1 [25] [3].

Cell Viability and Morphology Problems

Problem: Poor Adherence or Viability in Differentiated Macrophages

- Potential Cause: Overexposure to high PMA concentrations in cell line models or insufficient M-CSF in primary differentiations.

- Solution: For THP-1 models, use lower PMA concentrations (5-10 ng/mL) and limit exposure to 24-48 hours [25] [23]. For BMDMs, ensure adequate M-CSF concentration and refresh media every 2-3 days.

- Technical Note: PMA concentrations below 5 ng/mL reduce THP-1 adherence, while concentrations above 100 ng/mL cause cellular toxicity [23].

Problem: Unexpected Morphological Changes Post-Polarization

- Expected Morphologies: M1 macrophages typically exhibit flattened, pancake-like morphology with increased pseudopodia [21] [23]. M2 macrophages appear flattened and elongated with less densely distributed filopodia [23].

- Troubleshooting: If cells display unexpected morphology, verify cytokine activity and check for microbial contamination. Ensure polarization stimuli are prepared in appropriate vehicles with proper pH and osmolarity.

Species-Specific Discrepancies

Problem: Human vs. Mouse Macrophage Response Differences

- Key Example: Mouse macrophages robustly express iNOS and produce NO in response to IFN-γ + LPS, while human macrophages often show minimal iNOS expression and NO production in vitro despite abundant iNOS in human tissue samples [26].

- Solution: Recognize fundamental species differences and avoid over-interpreting negative results in human macrophage assays. Consider using tissue-derived macrophages or alternative activation markers for human studies [26].

- Technical Consideration: Human macrophages derived from donor monocytes differentiated in vitro in RPMI with CSF-1 may lack factors permissive for iNOS expression present in vivo [26].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Macrophage Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solution | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Polarization Efficiency | Suboptimal cytokine concentrations, degraded reagents, insufficient stimulation time | Use fresh aliquots, optimize concentration and duration, include positive controls | Measure multiple markers at protein and gene levels (CD86, iNOS for M1; CD206, Arg1 for M2) |

| High Cell Death Post-Differentiation | Excessive PMA concentration (THP-1), insufficient growth factors, contamination | Titrate PMA (5-10 ng/mL), ensure adequate M-CSF, check sterility | Monitor morphology, use viability dyes, check adherence |

| Inconsistent Results Between Experiments | Donor variability (primary cells), passage number effects (cell lines), serum batch effects | Standardize donor criteria, use low-passage cells, use same serum batch | Include reference standards in each experiment |

| Weak Marker Expression | Inadequate polarization, wrong detection methods, antibody issues | Optimize polarization protocol, validate antibodies, try multiple detection methods | Use qRT-PCR and flow cytometry, confirm with functional assays |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Macrophage Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Factors | M-CSF (CSF-1), PMA (Phorbol ester) | Induces monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation | M-CSF for primary cells (5-7 days), PMA for THP-1 (24-48 hours at 5-100 ng/mL) [25] [21] [23] |

| M1 Polarization Stimuli | IFN-γ, LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Classical macrophage activation | Combined use (IFN-γ: 50 ng/mL + LPS: 15-100 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours [23] [3] |

| M2 Polarization Stimuli | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10 | Alternative macrophage activation | IL-4/IL-13 for M2a (20-25 ng/mL, 48-72h), IL-10 for M2c (10 ng/mL, 24-72h) [23] |

| Key Antibodies for Characterization | Anti-CD86, Anti-iNOS, Anti-CD206, Anti-CD163 | Marker detection for polarized phenotypes | Use multiple markers for validation; CD163 specifically marks M(IL-10) but not M(IL-4) macrophages [25] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | JAK inhibitors (e.g., Ruxolitinib), NF-κB inhibitors | Pathway analysis and mechanistic studies | Use for validating signaling mechanisms in polarization [24] |

Technical Notes: Critical Considerations for Model Selection

Model-Specific Advantages and Limitations

BMDMs offer high physiological relevance with potent secretory activity, strong phagocytic capability, and pronounced polarization plasticity, making them ideal for metabolic studies and validation of genetic knockout models [21] [22]. However, they require technically challenging isolation and a 5-7 day differentiation period, with polarization status potentially being age-dependent [21] [22].

PBMC-Derived Macrophages provide human-specific responses but suffer from diverse genetic backgrounds and significant individual differences [23]. They are terminally differentiated, non-proliferative cells that cannot be passaged [21].

Tissue-Resident Macrophages (e.g., Kupffer cells, microglia) maintain tissue-specific functions but are extremely difficult to isolate with low yield and cannot be cultured long-term [21].

Standardization Recommendations

For reproducible results across experiments:

- Passage Number Control: Use low-passage cells and report passage numbers to enhance cross-study comparability [21].

- Serum Batch Consistency: Use the same serum batch throughout a study to minimize variability.

- Comprehensive Characterization: Employ multiple markers (both surface and transcriptional) to validate polarization states, as no single marker is entirely specific [25] [23].

- Functional Validation: Include functional assays (phagocytosis, cytokine secretion) alongside marker expression to confirm phenotypic polarization.

Diagram 2: Macrophage Model Selection Workflow. This decision diagram illustrates the key considerations when selecting appropriate macrophage models for research, highlighting the advantages and limitations of each primary model type.

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Questions

Q1: What is the minimum PMA concentration required for effective THP-1 differentiation, and why does concentration matter? A: The minimum effective PMA concentration is 5 ng/mL, with concentrations below this resulting in inadequate THP-1 adherence and differentiation. Higher PMA concentrations (above 100 ng/mL) cause cellular toxicity and can compromise the ability to polarize to M2 phenotypes [25] [23]. The optimal range is 5-10 ng/mL for 24-48 hours.

Q2: Why do my human macrophages not produce nitric oxide (NO) like mouse macrophages when stimulated with LPS and IFN-γ? A: This represents a fundamental species difference between mouse and human macrophages. While mouse BMDMs readily express iNOS and produce NO in response to IFN-γ + LPS, human macrophages often show minimal iNOS expression and NO production in vitro, despite abundant iNOS detection in human tissue samples [26]. This discrepancy may reflect differences in culture conditions rather than true functional differences.

Q3: How long should I rest THP-1 cells after PMA treatment before polarization? A: Resting PMA-treated THP-1 cells for 24 hours before polarization attempts results in a phenotype more similar to M(IFN-γ+LPS) human monocyte-derived macrophages, with increased transcription of inflammatory cytokines like TNF and IL-1β [25]. This rest period allows for stabilization of the differentiated state.

Q4: What are the most reliable markers for confirming human macrophage polarization? A: Use multiple markers for validation. For M1: CD80, CD86, iNOS, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12). For M2: CD206, CD163 (specifically for M(IL-10)), CCL17, CCL22, and ALOX15 [25] [23]. No single marker is entirely specific, so a combination approach is recommended.

Q5: How does macrophage plasticity affect long-term polarization experiments? A: Macrophage polarization is temporary and reversible, with macrophages able to switch phenotypes upon encountering new microenvironmental cues [26] [24]. This plasticity means that maintained polarization requires persistent stimulation, and phenotype should be verified at experiment endpoints rather than assuming maintained polarization after initial induction.

This technical support center resource is designed to assist researchers in the selection and application of three widely used immortalized cell lines in macrophage and immunology research: THP-1, RAW 264.7, and U-937. Framed within the critical context of standardizing macrophage polarization protocols across experimental models, this guide provides detailed troubleshooting advice, comparative data, and standardized methodologies to enhance experimental reproducibility and reliability. The content is specifically curated for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust, consistent in vitro models for studying immune responses.

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each cell line to inform model selection.

| Feature | THP-1 | RAW 264.7 | U-937 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Human [27] | Mouse (Murine) [28] | Human [29] |

| Origin | Acute Monocytic Leukemia (blood of a 1-year-old male) [30] [27] | Abelson Murine Leukemia Virus-induced tumor (BALB/c mouse) [28] | Histiocytic Lymphoma (pleural effusion of a 37-year-old male) [29] [30] |

| Morphology & Growth | Monocytic; grows in suspension [27] | Macrophage-like; semi-adherent [28] | Pro-monocytic; grows in suspension [29] |

| Primary Research Applications | Human immunology, dendritic cell differentiation, skin sensitization (h-CLAT) [27] [31] | Murine immunology, osteoclastogenesis, phagocytosis studies [28] [32] | Human monocyte biology, cancer research, toxicology [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists critical reagents and their functions for culturing and differentiating these cell lines.

| Reagent | Function | Application Across Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Standard growth medium for leukemic and immune cells [28] [29] [27] | Used for culturing THP-1, U-937, and RAW 264.7 [28] [29] [27] |

| Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate (PMA) | Protein Kinase C (PKC) activator; induces differentiation into adherent macrophage-like cells [33] [27] | Used to differentiate THP-1 and U-937 from monocytes to macrophages [30] [27] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | TLR4 agonist; induces pro-inflammatory M1 polarization [34] | Common stimulant for all three lines to model inflammatory responses [28] [34] |

| Recombinant Cytokines (e.g., IL-4) | Key signaling proteins for directing macrophage polarization [34] | IL-4 is used to promote anti-inflammatory M2 polarization in all models [34] [30] |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides essential nutrients, growth factors, and hormones for cell survival and proliferation [27] | Standard supplement (typically 10%) for the growth media of THP-1, U-937, and RAW 264.7 [28] [29] [33] |

Standardized Polarization Protocols & Workflows

Achieving consistent macrophage polarization is critical for reproducible research. The following workflow diagrams and protocols are designed to serve as a standardization framework.

Human Monocyte (THP-1 & U-937) Differentiation and Polarization

The diagram below outlines the core process for differentiating and polarizing human monocytic cell lines.

Detailed Protocol:

- Culture Monocytes: Maintain THP-1 or U-937 cells in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO₂ [29] [27].

- Differentiate into Macrophages (M0): Seed cells and treat with 100 ng/mL PMA for 48 hours. Gently wash with PBS to remove non-adherent cells and residual PMA. Rest the adherent macrophages in fresh complete medium for at least 24 hours before polarization [30] [27].

- Polarize to M1: Stimulate M0 macrophages with LPS (e.g., 100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (e.g., 20 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours [30].

- Polarize to M2: Stimulate M0 macrophages with IL-4 (e.g., 20 ng/mL) and IL-13 for 24-48 hours [30].

RAW 264.7 Macrophage Polarization

The murine RAW 264.7 line, being more mature, can be polarized directly from its basal state.

Detailed Protocol:

- Culture RAW 264.7 Cells: Maintain this semi-adherent line in RPMI 1640 or DMEM with 10% FBS. Culture in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO₂. The population doubling time ranges from 11 to 30 hours [28].

- Polarize to M1: Stimulate cells directly with LPS (e.g., 100 ng/mL) for 24 hours [34].

- Polarize to M2: Stimulate cells directly with IL-4 (e.g., 50 ng/mL) for 24 hours [34].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Cell Culture and Health

Q: My THP-1 cells are clumping excessively in suspension. What should I do? A: Some clumping is normal, but excessive clumping can hinder growth. Gently homogenize the cell suspension before assays. Centrifugation to remove dead cells, which can promote clumping, is also recommended. Ensure cells are maintained at an optimal density between 3x10⁵ and 7x10⁵ cells/mL [33].

Q: My RAW 264.7 cells are difficult to detach due to strong adhesion. How can I improve this? A: Strong adhesion is a known characteristic of this line [28]. Use cell scrapers for detachment, though this may be more stressful to cells. Alternatively, pre-warm the recommended dissociation solution (e.g., trypsin-EDTA) and ensure it covers the monolayer completely. Monitor the cells under a microscope to avoid over-trypsinization.

Q: What is the recommended seeding density for freezing U937 cells? A: U937 cells should be frozen at a density of approximately 1 x 10⁶ cells/mL in freezing medium such as CM-1 or CM-ACF, using a slow-freezing process to maximize viability upon thawing [29].

Differentiation and Polarization

Q: After PMA differentiation, my THP-1 macrophages show high background in reporter assays. Why? A: PMA is a potent activator of PKC and NF-κB. High background is common if assays are performed too soon after differentiation. It is highly recommended to wait at least 72-96 hours after PMA treatment and subsequent washing before performing reporter assays to allow the signaling background to normalize [33].

Q: How stable is the M2-polarized phenotype in these cell lines? A: The M2 phenotype can be unstable, particularly in pro-inflammatory microenvironments. Research shows that M2-polarized RAW 264.7 cells can revert towards an M1-like state when transferred into an inflammatory context (e.g., an ARDS mouse model) [34]. This underscores the importance of validating polarization status at the endpoint of your experiment.

Q: Are there inherent biases in the polarization responses of THP-1 and U-937 cells? A: Yes. Under standardized differentiation and polarization conditions, THP-1-derived macrophages are more responsive to M1 stimuli and are skewed towards an M1 phenotype. In contrast, U-937-derived macrophages are more responsive to M2 stimuli and are skewed towards an M2 phenotype [30]. This intrinsic bias must be considered when selecting a model for your research question.

Model Selection and Data Interpretation

Q: Can RAW 264.7 cells be used to study osteoclastogenesis? A: Yes. While not osteoclasts themselves, RAW 264.7 cells can be differentiated into osteoclast-like cells upon stimulation with RANKL. These differentiated cells are capable of bone resorption and are a well-established model for studying bone remodeling and related diseases like osteoporosis [28] [32].

Q: Why might my results from an immortalized cell line differ from those using primary macrophages? A: Immortalized cell lines, being derived from cancers, often have chromosomal abnormalities and may exhibit genotypic and phenotypic drift over time in culture [29] [21]. They can differ from primary macrophages in gene expression, phenotype, and functional responses [28] [21]. While they offer reproducibility and ease of use, critical findings should be validated in primary cells where possible.

Q: Which cell line is best suited for studying phagocytosis? A: All three lines possess phagocytic capability, but their efficiency differs. Studies indicate that THP-1-derived macrophages generally exhibit greater phagocytic activity and produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS) compared to U-937-derived macrophages [30]. RAW 264.7 is also extensively used for phagocytosis studies due to its robust macrophage-like functions [28] [32].

Macrophage polarization is a fundamental process in immunology where macrophages, highly plastic immune cells, differentiate into distinct functional phenotypes in response to environmental signals. This process is typically categorized within the M1/M2 paradigm, where classically activated M1 macrophages exhibit pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor properties, and alternatively activated M2 macrophages display anti-inflammatory, pro-tumor characteristics [15]. The polarization process is controlled by specific cytokines, timing, and concentration parameters that determine the resulting macrophage phenotype and function. Standardization of these parameters is crucial for experimental reproducibility and meaningful comparison across studies, particularly in the context of disease modeling and therapeutic development [35] [26].

The M1/M2 classification, while useful, represents an oversimplification of macrophage biology. Single-cell transcriptomics has revealed that macrophage phenotypes exist along a dynamic continuum rather than discrete categories, exhibiting remarkable plasticity shaped by local microenvironmental cues, developmental origins, and disease-specific contexts [15]. This complexity underscores the importance of carefully controlled polarization protocols to generate well-defined macrophage populations for research and therapeutic applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Why do I observe inconsistent expression of polarization markers between experiments despite using the same stimuli?

A1: Inconsistent marker expression most commonly results from suboptimal stimulation timing. The expression of polarization markers changes dynamically over time, and analyzing markers at incorrect time points can yield false-negative results. For human monocyte-derived macrophages, key M1 markers like TNF and IL-12 peak around 12-24 hours, while M2a markers like CCL17 and CCL22 require 48-72 hours for optimal expression [35]. Standardize your time points based on comprehensive time-course analyses and validate multiple markers simultaneously to confirm polarization status.

Q2: My M2-polarized macrophages are not exhibiting the expected functional properties. What could be wrong?

A2: This issue often stems from insufficient polarization duration or incorrect cytokine concentrations. For complete M2 polarization using the THP-1 model, a prolonged 14-day protocol with adequate rest periods is essential. This includes 72 hours of PMA treatment (100 ng/mL) followed by 96 hours of rest, then polarization with IL-4 and IL-13 (20 ng/mL each) for 48 hours, repeated twice [36] [37]. Ensure you include proper rest periods to allow inflammatory responses from mechanical stress or PMA treatment to subside before polarization.

Q3: How can I improve the reproducibility of macrophage polarization in my experiments?

A3: Key strategies include:

- Using low-passage cells and consistent cell densities

- Implementing standardized "rest periods" after differentiation before polarization

- Pre-testing cytokine batches for activity

- Using multiple validation methods (surface markers, cytokine secretion, gene expression)

- Including both positive and negative controls in every experiment

- Accounting for differences between primary cells and cell lines like THP-1 [36] [35]

Q4: What are the critical differences between mouse and human macrophage polarization that I should consider?

A4: Significant species differences exist in marker expression and functional responses. Mouse M1 macrophages express inducible NO synthase (iNOS), while human M1 macrophages do not. Similarly, murine M2a macrophages express Arg1, Ym1, and Fizz1, but these genes lack human homologs [35] [26]. THP-1 cells also differ from primary human macrophages in their response to LPS and expression of HLA-DR and CD206 [35]. Always validate findings across species and model systems.

Q5: Why do my macrophages seem to display mixed M1/M2 characteristics?

A5: Macrophages exist along a spectrum rather than in binary states, and simultaneous or sequential exposure to different stimuli can create hybrid phenotypes [15] [26]. Ensure your polarization stimuli are not contaminated with opposing cytokines, and verify that your culture conditions are consistent. Some degree of heterogeneity is normal, but excessive mixing suggests suboptimal polarization conditions.

Quantitative Data for Polarization Optimization

Table 1: Optimal Time Points for Human Macrophage Polarization Markers

| Polarization | Marker Type | Marker | Optimal Time (mRNA) | Optimal Time (Protein) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (LPS + IFN-γ) | Surface | CD64, CD86 | 24-48 hours | 48-72 hours | HLA-DR peaks at 48-72h |

| M1 (LPS + IFN-γ) | Cytokine | TNF | 4-8 hours | 8-24 hours | Early response marker |

| M1 (LPS + IFN-γ) | Cytokine | IL-12 | 12-24 hours | 24-48 hours | Later response marker |

| M1 (LPS + IFN-γ) | Chemokine | CXCL10 | 12-24 hours | 24-48 hours | Sustained expression |