The Oxidative-Inflammatory Axis in Chronic Disease: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Chronic diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative disorders, share a common pathological denominator: a self-perpetuating cycle of oxidative stress and inflammation.

The Oxidative-Inflammatory Axis in Chronic Disease: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

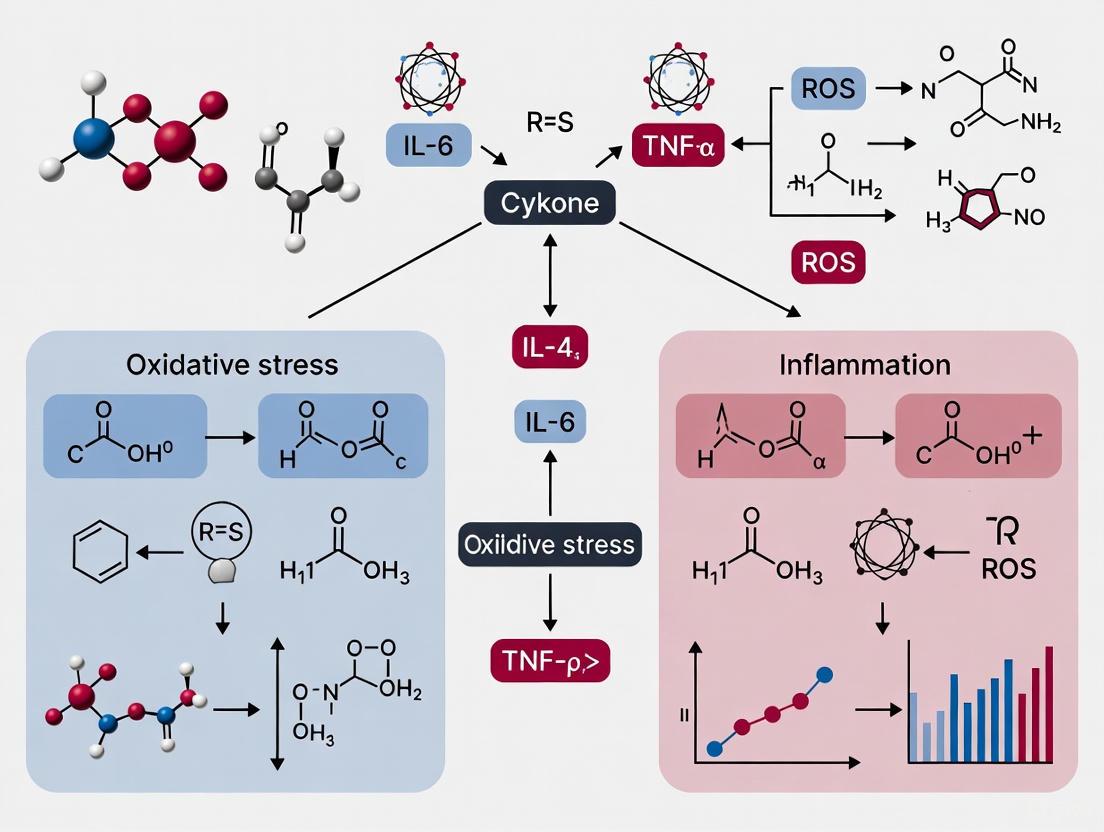

Chronic diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative disorders, share a common pathological denominator: a self-perpetuating cycle of oxidative stress and inflammation. This review provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, integrating foundational molecular mechanisms with translational applications. We explore the critical interplay between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB and Nrf2, which drives disease progression. The article critically assesses current methodologies for quantifying oxidative stress biomarkers and evaluates the paradoxical failure of conventional antioxidant trials. Furthermore, we detail innovative therapeutic strategies designed to overcome these limitations, such as mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, Nrf2 activators, and nanotechnology-based delivery systems. By synthesizing foundational knowledge, methodological applications, troubleshooting insights, and comparative validation data, this article aims to chart a course for developing effective, personalized redox medicine interventions.

Unraveling the Vicious Cycle: Core Molecular Mechanisms Linking ROS and Inflammatory Signaling

The interplay between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and chronic low-grade inflammation represents a core pathogenic axis in a wide spectrum of chronic diseases. This whitepaper delineates the key molecular players and mechanisms underpinning this relationship, focusing on the transition from acute, protective inflammatory responses to a state of persistent, pathological signaling. We detail the cellular sources of ROS, the redox-sensitive signaling pathways they activate, and the consequent perpetuation of a pro-inflammatory milieu. Furthermore, we provide a structured analysis of quantitative data, experimental protocols for key investigations, and visualizations of critical pathways. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a consolidated, technical framework for advancing therapeutic strategies that target the ROS-inflammation nexus.

Inflammation is a fundamental defensive response conferred by the host against pathogenic insults and tissue injury [1]. While acute inflammation is a protective mechanism, its dysregulation leads to a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that underpins numerous pathological conditions, including cardiovascular disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic syndromes, and autoimmune disorders [1] [2] [3]. Central to this dysregulation is the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Historically viewed merely as cytotoxic by-products of metabolism, ROS are now recognized as critical signaling molecules that regulate the progression of inflammatory disorders [1] [4].

The relationship between ROS and inflammation is synergistic and self-perpetuating. An enhanced generation of ROS at the site of inflammation contributes to endothelial dysfunction and tissue injury [1]. In turn, inflammatory mediators can stimulate the production of more ROS, creating a pathogenic feedback loop that sustains chronic inflammation even in the absence of an initial trigger [3]. This paper will define the key players in this process, from the specific ROS and their cellular sources to the signaling pathways they influence, within the broader context of oxidative stress and inflammation interplay in chronic disease research.

ROS are a class of partially reduced metabolites of oxygen with strong oxidizing capabilities. They function as double-edged swords: at low, physiological concentrations, they are indispensable signaling molecules, but at high, chronic concentrations, they oxidize cellular macromolecules, leading to damage and heightened inflammatory responses [1] [4].

Table 1: Key Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in Inflammation

| Reactive Species | Chemical Formula/Symbol | Primary Production Source | Reactivity and Role in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide anion | O₂•⁻ | Mitochondrial ETC, NADPH oxidases (NOX), Xanthine Oxidase [1] [2] | Precursor to most other ROS; short half-life; can reduce and inactivate nitric oxide [1] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H₂O₂ | Dismutation of O₂•⁻ by SOD, NOX4, DUOX [1] [2] | Membrane-permeable signaling molecule; can be converted to highly reactive OH• [3] |

| Hydroxyl radical | OH• | Fenton reaction (H₂O₂ + Fe²⁺) [1] [2] | Most potent oxidant; causes severe damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [2] |

| Hypochlorous acid | HOCl | Myeloperoxidase (MPO) conversion of H₂O₂ [1] | Powerful microbial agent; can cause host tissue damage during inflammation [1] |

| Nitric oxide | NO• | Nitric oxide synthases (e.g., iNOS) [3] | Gasotransmitter; reacts with O₂•⁻ to form peroxynitrite [1] |

| Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻ | Reaction between NO• and O₂•⁻ [2] [3] | Potent nitrating agent; induces nitrosative stress, damaging lipids, proteins, and DNA [2] |

The cellular generation of ROS is governed by multiple enzymatic and non-enzymatic sources. The major endogenous sources include:

- Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain (ETC): During oxidative phosphorylation, an estimated 1–3% of electrons leak from complexes I and III, mediating the one-electron reduction of oxygen to O₂•⁻, which is then dismutated to H₂O₂ [2] [4].

- NADPH Oxidases (NOX): This family of enzymes, including NOX1–NOX5 and DUOX1/2, is dedicated to the regulated production of ROS. They catalyze the transfer of electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen, generating O₂•⁻ or H₂O₂. NOX2, in particular, is critical for the "respiratory burst" in phagocytes for microbial killing [1] [3] [4].

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): Oxidative protein folding in the ER involves enzymes like Ero1 and PDI, which can produce H₂O₂ as a by-product, particularly under conditions of ER stress [3].

- Xanthine Oxidase (XO): This enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and then to uric acid, generating O₂•⁻ and H₂O₂ in the process [1] [4].

Signaling Pathways: The Mechanism of ROS-Mediated Inflammation

ROS propagate inflammation primarily by activating redox-sensitive signaling pathways. The following pathways are paramount in this process.

The NF-κB Pathway

The Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway is a master regulator of inflammation and is exquisitely sensitive to redox balance [3] [5].

Title: ROS activation of the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway.

Mechanism: In resting cells, NF-κB dimers (e.g., p50/p65) are sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory proteins, IκBs. A wide array of pro-inflammatory stimuli (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, LPS) and ROS itself can activate the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. ROS, particularly H₂O₂, can oxidize critical cysteine residues in IKK, leading to its activation [3] [5]. Activated IKK phosphorylates IκB, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This releases NF-κB, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus and induce the transcription of over 150 target genes, including those encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), adhesion molecules, and enzymes like cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [3] [5]. The induction of iNOS further increases NO• production, which can react with O₂•⁻ to form the damaging peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), thereby amplifying oxidative stress and inflammation [1] [3].

The Nrf2/Keap1 Pathway

In opposition to NF-κB, the Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is a central regulator of cellular defense against oxidative stress and exerts anti-inflammatory effects [3] [5].

Title: Nrf2 activation by ROS leads to cytoprotective gene expression.

Mechanism: Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to its cytosolic repressor, Keap1, which constantly targets Nrf2 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, keeping its levels low. Oxidative stress or electrophiles modify critical cysteine residues on Keap1, leading to a conformational change that disrupts its ability to target Nrf2 for degradation. Consequently, Nrf2 stabilizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it heterodimerizes with small Maf proteins and binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) in the promoter regions of its target genes [3] [5]. This activates the transcription of a battery of cytoprotective genes, including those encoding heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), a rate-limiting enzyme in glutathione synthesis. By enhancing the cellular antioxidant capacity, Nrf2 activation indirectly suppresses inflammation, notably by inhibiting NF-κB signaling and modulating macrophage polarization [3] [5].

Inflammasome Activation

ROS are key mediators in the activation of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a multiprotein complex critical for the innate immune response [3].

Mechanism: Multiple DAMPs and PAMPs can prime the inflammasome by upregulating NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression via pathways like NF-κB. A second signal, which often involves ROS (particularly mitochondrial ROS), triggers inflammasome assembly. The assembled inflammasome activates caspase-1, which then cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active, secreted forms. These potent pyrogenic cytokines drive inflammatory responses in conditions like gout, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer's disease [3].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Analysis

To facilitate research, key quantitative data on ROS and antioxidants are summarized below.

Table 2: Key Enzymatic Antioxidant Defenses and Their Roles

| Antioxidant Enzyme | Isoforms / Location | Reaction Catalyzed | Role in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | SOD1 (cytosol), SOD2 (mitochondria), SOD3 (extracellular) [2] [3] | 2 O₂•⁻ + 2H⁺ → H₂O₂ + O₂ [1] [2] | First line of defense; converts O₂•⁻ to the less reactive H₂O₂. Its dysregulation allows O₂•⁻ to accumulate and form ONOO⁻. |

| Catalase (CAT) | Primarily peroxisomes [2] | 2 H₂O₂ → 2 H₂O + O₂ [4] | Crucial for removing high concentrations of H₂O₂, preventing its conversion to the highly damaging OH• via Fenton chemistry. |

| Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) | GPx1 (cytosol, mitochondria), GPx4 (membrane) [2] | H₂O₂ + 2 GSH → GSSG + 2 H₂O (or organic hydroperoxides) [4] | Plays a major role in H₂O₂ clearance at lower concentrations; maintains cellular redox balance via the GSH/GSSG ratio. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying ROS and Inflammation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in the Field |

|---|---|---|

| NOX Inhibitors (e.g., GKT136901, VAS2870) | Pharmacologically inhibit specific NADPH oxidase isoforms to dissect their contribution to ROS production and inflammatory signaling. | Used to demonstrate NOX4's role in endothelial cell inflammation and fibrosis models [1]. |

| Nrf2 Activators (e.g., sulforaphane, CDDO-Me) | Stabilize Nrf2 by modifying Keap1 cysteine residues, inducing ARE-driven gene expression for experimental or therapeutic purposes. | Preclinical studies use sulforaphane to boost antioxidant defenses and mitigate inflammation in models of metabolic syndrome [3] [5]. |

| ROS-Sensitive Fluorescent Probes (e.g., DCFH-DA, MitoSOX Red) | Detect and quantify general cellular ROS (DCFH-DA) or mitochondrial superoxide (MitoSOX) via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. | Standard tools for confirming increased ROS generation in immune cells upon stimulation with TNF-α or LPS [1] [4]. |

| NF-κB Reporter Cell Lines | Engineered cells containing a luciferase gene under the control of an NF-κB response element; used to screen for pro- or anti-inflammatory compounds. | Used in high-throughput screens to identify novel compounds that inhibit ROS-induced NF-κB activation [3] [5]. |

| ELISA/Kits for Biomarkers | Quantify protein levels of oxidative damage markers (e.g., 3-nitrotyrosine, 4-HNE) or inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α). | Essential for correlating oxidative stress with inflammatory burden in cell culture supernatants, plasma, or tissue homogenates [3] [4]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

To investigate the interplay between ROS and inflammation, robust and reliable experimental methodologies are required. Below are detailed protocols for two fundamental assays.

Protocol: Measuring Intracellular ROS using DCFH-DA

Principle: The cell-permeable dye 2',7'-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) is deacetylated by cellular esterases to non-fluorescent DCFH, which is trapped inside the cell. Upon oxidation by intracellular ROS (primarily H₂O₂ and peroxidases), it is converted to highly fluorescent 2',7'-Dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Fluorescence intensity is proportional to ROS levels.

Materials:

- DCFH-DA reagent (prepare a 10-20 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or appropriate cell culture medium without serum

- Cells of interest (e.g., endothelial cells, macrophages) cultured in a 96-well black-walled plate

- Positive control (e.g., 100-500 µM tert-Butyl hydroperoxide, tBHP)

- Fluorescent microplate reader or flow cytometer

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Seed and culture cells to 70-80% confluency. Prior to treatment, wash the cells twice with pre-warmed, serum-free medium or PBS.

- Dye Loading: Incubate cells with 10-20 µM DCFH-DA in serum-free medium for 30-60 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Carefully remove the DCFH-DA solution and wash the cells twice with PBS to remove any extracellular dye.

- Treatment and Measurement:

- For kinetic studies: Add fresh medium with or without the test compounds/inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS, TNF-α) and immediately place the plate in a fluorescent microplate reader. Measure fluorescence (Ex/Em ~485/535 nm) at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes for 2-4 hours).

- For endpoint analysis: Incubate cells with treatments for a desired period, then measure fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence data to protein content (via BCA assay) or cell number. Express results as fold-change relative to the untreated control.

Protocol: Assessing NF-κB Activation via Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Principle: EMSA is used to detect protein-DNA interactions. It measures the binding of nuclear extract proteins, specifically NF-κB, to a radiolabeled or chemiluminescent DNA probe containing the κB consensus sequence. The protein-DNA complex has reduced mobility in a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Materials:

- Nuclear Extract Kit (e.g., NE-PER Kit)

- Double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the κB consensus sequence (5'-GGGACTTTCC-3')

- T4 Polynucleotide Kinase and [γ-³²P]ATP or biotin end-labeling kit

- Non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system

- Buffers: Binding buffer, poly(dI•dC) as non-specific competitor

- Autoradiography film or chemiluminescence detection system

Method:

- Nuclear Extraction: Harvest control and treated cells (e.g., with ROS or TNF-α). Prepare nuclear extracts according to the commercial kit's instructions. Determine protein concentration.

- Probe Labeling: Label the κB oligonucleotide probe with [γ-³²P]ATP using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase, or with biotin. Purify the labeled probe.

- Binding Reaction: In a total volume of 20 µL, incubate 5-10 µg of nuclear extract with the labeled probe (50,000-100,000 cpm) in binding buffer containing poly(dI•dC) and other components for 20-30 minutes at room temperature.

- For specificity control (supershift): Pre-incubate the nuclear extract with an antibody against a specific NF-κB subunit (e.g., p65) for 15-30 minutes before adding the probe.

- For competition control: Include a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled (cold) κB probe to demonstrate binding specificity.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load the reactions onto a pre-run, non-denaturing 4-6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5x TBE buffer. Run the gel at 100-150 V at 4°C until the dye front is near the bottom.

- Detection:

- For radioactive probes: Dry the gel and expose it to X-ray film at -80°C or use a phosphorimager.

- For biotinylated probes: Transfer the DNA-protein complexes to a positively charged nylon membrane, crosslink, and detect using a chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module.

- Analysis: The presence of a shifted band indicates NF-κB binding. A supershifted band (higher molecular weight) confirms the identity of the subunit in the complex.

The transcription factor NF-κB serves as a critical molecular bridge connecting reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling to inflammatory gene expression. This whitepaper examines the sophisticated mechanisms through which ROS activate NF-κB and how this pathway initiates and sustains inflammatory responses relevant to chronic diseases. We provide a comprehensive analysis of the bidirectional regulatory relationships, experimental methodologies for studying this pathway, and quantitative data on redox-sensitive molecular components. Understanding these mechanisms provides a rational basis for therapeutic interventions targeting oxidative stress-linked inflammatory conditions, including metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions.

Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB represents a family of inducible transcription factors that function as pivotal mediators of inflammatory responses, immune regulation, and cell survival [6]. Initially identified in 1986 as a nuclear factor binding to the kappa enhancer in B-cells, NF-κB is now recognized as a ubiquitously expressed stress response factor activated by diverse stimuli, including cytokines, pathogens, and oxidative stress [7]. The functional interplay between ROS and NF-κB establishes a fundamental signaling axis that drives pathological inflammation in chronic diseases. Under physiological conditions, this system maintains immune vigilance, but when dysregulated, it perpetuates a cycle of oxidative damage and inflammation that characterizes conditions such as atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegenerative disorders [3].

The redox sensitivity of NF-κB positions it as a key sensor of cellular oxidative status, translating biochemical changes in ROS concentrations into transcriptional programs. This pathway exemplifies how oxidative stress extends beyond random macromolecular damage to encompass highly organized signaling processes that can be therapeutically targeted. The following sections delineate the molecular architecture of NF-κB signaling, its precise mechanisms of redox regulation, experimental approaches for its investigation, and its pathophysiological significance in human disease.

Molecular Architecture of the NF-κB Signaling System

NF-κB Protein Family

The NF-κB family comprises five structurally related members that form various homo- and heterodimers with distinct regulatory functions and DNA-binding specificities [7]:

- NF-κB1 (p105/p50): Processed from its p105 precursor to the mature p50 form, which lacks a transactivation domain

- NF-κB2 (p100/p52): Processed from p100 to p52, similarly lacking transactivation capability

- RelA (p65): Contains a transactivation domain and is the major transcriptional activator

- RelB: Partners with p52 in the non-canonical pathway

- c-Rel: Important in immune cell responses and inflammation

The most abundant and well-characterized NF-κB dimer is the p50/RelA heterodimer, which serves as the primary effector of the canonical pathway [8]. All family members share a conserved Rel homology domain (RHD responsible for DNA binding, dimerization, and interaction with inhibitory proteins [7].

Inhibitory IκB Proteins and IKK Complex

In unstimulated cells, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins, which mask nuclear localization sequences and prevent DNA binding [8]. The IκB family includes:

- Typical IκBs (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε): Mainly cytoplasmic, containing ankyrin repeats that mediate NF-κB binding

- Atypical IκBs (IκBζ, Bcl-3, IκBNS): Nuclear proteins that can either repress or activate specific NF-κB dimers

- Precursor proteins (p105 and p100): Function as IκB-like molecules through their C-terminal ankyrin repeat domains

The activation of NF-κB requires signal-induced phosphorylation of IκB proteins by the IκB kinase (IKK complex, which consists of two catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ and a regulatory subunit (NEMO/IKKγ) [7]. Phosphorylation targets IκB for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, liberating NF-κB for nuclear translocation.

ROS-Mediated Activation of NF-κB Signaling

Canonical NF-κB Pathway Activation

The canonical NF-κB pathway responds to numerous stimuli including proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, bacterial products (LPS, and ROS [6]. As shown in Figure 1, ROS influence multiple steps in this activation cascade:

Figure 1: ROS activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway

ROS influence multiple steps in NF-κB activation: (1) ROS can directly activate IKK through oxidative modification; (2) ROS inhibit phosphatases that normally suppress NF-κB signaling; (3) ROS promote the dissociation of NF-κB from IκB by enhancing IκB degradation; (4) In the nucleus, ROS can both inhibit and enhance DNA binding depending on concentration and cellular redox state.

Key Redox-Sensitive Molecular Targets in NF-κB Activation

Multiple components of the NF-κB signaling cascade demonstrate redox sensitivity through modification of critical cysteine residues:

Table 1: Redox-Sensitive Sites in the NF-κB Pathway

| Target Molecule | Redox Modification | Functional Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKKβ | Oxidation of Cys-179 | Inhibition of kinase activity | H₂O₂ treatment inhibits TNF-α-induced IKK activity [8] |

| p50 subunit | Oxidation of Cys-62 | Decreased DNA binding capacity | Spatial regulation with oxidation in cytoplasm, reduction in nucleus [8] |

| NIK | Oxidation-induced activation | Enhanced IKKα phosphorylation | IL-1β treatment increases ROS-mediated NIK activation [8] |

| LC8 (dynein light chain) | Redox-dependent dissociation from IκBα | Allows IκBα phosphorylation | ROS oxidizes LC8, promoting NF-κB activation [8] |

| Ref-1 | Reduction of p50 | Enhanced DNA binding | Nuclear Ref-1 reduces Cys-62, restoring DNA binding [8] |

Biphasic and Context-Dependent ROS Effects

The relationship between ROS and NF-κB activation demonstrates complex biphasic characteristics. While moderate oxidative stress typically activates NF-κB, sustained or severe oxidative stress can inhibit NF-κB signaling through multiple mechanisms [8]:

- Early phase activation: Low to moderate ROS levels promote IKK activation and IκB degradation

- Sustained oxidative stress: Leads to proteasome inhibition, preventing IκB degradation and NF-κB activation

- Direct oxidative inhibition: High ROS levels oxidize critical cysteine residues in NF-κB subunits, impairing DNA binding

This biphasic relationship explains seemingly contradictory findings in the literature and underscores the importance of considering ROS concentration, timing, and cellular context when investigating this pathway.

NF-κB-Dependent Pro-Inflammatory Gene Expression

Upon activation and nuclear translocation, NF-κB dimers bind to specific κB enhancer elements in the promoters of target genes, initiating a pro-inflammatory transcriptional program. The specific gene repertoire induced depends on cell type, nature of the stimulus, and dimer composition.

Table 2: Major Categories of NF-κB Target Genes in Inflammation

| Gene Category | Specific Examples | Functional Role in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 | Amplify inflammatory signals; recruit immune cells |

| Chemokines | IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1α | Direct leukocyte migration to sites of inflammation |

| Adhesion Molecules | ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin | Mediate leukocyte endothelial adhesion and transmigration |

| Enzymes | iNOS, COX-2 | Produce inflammatory mediators (NO, prostaglandins) |

| Regulatory Proteins | IκBα (feedback inhibition) | Terminate NF-κB signaling through negative feedback |

NF-κB activation in specific cell types generates distinct inflammatory outcomes:

- Macrophages: NF-κB drives polarization toward pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype with enhanced cytokine production [6]

- Endothelial cells: NF-κB increases adhesion molecule expression, enhancing leukocyte recruitment and vascular inflammation [9]

- Neutrophils: NF-κB extends lifespan and promotes formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [9]

Interplay with Other Redox-Sensitive Pathways

Cross-Regulation with Nrf2 Antioxidant Pathway

The NF-κB pathway exhibits extensive cross-regulation with the Nrf2-Keap1 antioxidant system, creating a delicate balance between inflammatory and antioxidant responses:

Figure 2: NF-κB and Nrf2 pathway interactions

NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways interact through multiple mechanisms: (1) Competition for the transcriptional co-activator CBP, which can be limiting; (2) Nrf2 activation induces antioxidant genes that reduce ROS and indirectly suppress NF-κB; (3) NF-κB can modulate Nrf2 transcription and activity; (4) KEAP1, which normally targets Nrf2 for degradation, can also function as an IKKβ E3 ubiquitin ligase, linking the two pathways [8].

Feedback Loops and Oscillatory Dynamics

NF-κB signaling displays complex temporal dynamics characterized by oscillatory nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Negative feedback regulators, particularly IκBα and the deubiquitinase A20, ensure transient responses to stimulation rather than sustained activation [8]. ROS can modulate these feedback loops by:

- Influencing the synthesis and degradation of IκB proteins

- Modifying the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes

- Affecting proteasome function, which is crucial for IκB degradation and NF-κB activation

These dynamic features allow fine-tuned inflammatory responses appropriate to the stimulus intensity and duration, with dysregulation leading to chronic inflammation.

Experimental Approaches for Studying ROS-NF-κB Interactions

Establishing ROS-Dependent NF-κB Activation

To demonstrate ROS-mediated NF-κB activation, researchers employ a combination of pharmacological and genetic approaches:

Protocol 1: Verification of ROS-Dependent NF-κB Activation

- Stimulation: Treat cells with ROS-generating agents (H₂O₂ 100-500 μM; menadione 10-50 μM; TNF-α 10-50 ng/mL as a positive control)

- ROS inhibition: Pre-treat with antioxidants (N-acetylcysteine 5-20 mM; catalase-PEG 100-500 U/mL; Tempol 1-5 mM) 30-60 minutes prior to stimulation

- NF-κB activation assessment:

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): Measure NF-κB DNA binding in nuclear extracts

- Immunofluorescence microscopy: Visualize p65 nuclear translocation

- Western blotting: Analyze IκBα degradation and p65 phosphorylation

- Luciferase reporter assay: Quantify NF-κB transcriptional activity

Specific Molecular Target Identification

To pinpoint specific redox-sensitive cysteine residues in NF-κB pathway components:

Protocol 2: Identification of Redox-Sensitive Cysteine Residues

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Replace candidate cysteine residues with serine or alanine

- Mass spectrometry: Identify oxidized cysteine residues in immunoprecipitated proteins

- Functional assays:

- Kinase activity assays: For IKK mutants after oxidative treatment

- DNA binding assays: For NF-κB subunit mutants using EMSA

- Gene reporter assays: Compare transcriptional activity of redox-insensitive mutants

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ROS-NF-κB Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| ROS Inducers | H₂O₂, menadione, tert-butyl hydroperoxide | Experimental generation of oxidative stress |

| ROS Scavengers | N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Tempol, catalase-PEG | Antioxidants to establish ROS dependence |

| IKK Inhibitors | IKK-16, BMS-345541, SC-514 | Pharmacological inhibition of IKK complex |

| NF-κB Reporters | NF-κB luciferase constructs, GFP-p65 fusion proteins | Monitoring NF-κB activation and localization |

| Antibodies | Phospho-IκBα, phospho-p65, total p65, IKKγ | Detection of pathway activation by Western blot, IF |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA against Nrf2, Nox isoforms, NF-κB subunits | Gene-specific manipulation of pathway components |

Pathophysiological Implications in Chronic Diseases

The ROS-NF-κB axis contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of numerous chronic inflammatory conditions:

Metabolic Diseases

In obesity and type 2 diabetes, elevated ROS production from nutrient overload activates NF-κB in adipocytes, hepatocytes, and immune cells, driving chronic low-grade inflammation that promotes insulin resistance [3]. This establishes a vicious cycle where metabolic dysfunction generates oxidative stress, which perpetuates inflammation through NF-κB, further worsening metabolic parameters.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Atherosclerosis represents a classic example of redox-sensitive NF-κB activation in vascular pathology. ROS generated within atherosclerotic plaques activate NF-κB in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages, promoting expression of adhesion molecules, cytokines, and pro-coagulant factors [9]. NF-κB also contributes to the phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells from contractile to synthetic states, accelerating plaque progression.

Neurological Disorders

In ischemic stroke, reperfusion injury generates explosive ROS production through mitochondrial reverse electron transport, xanthine oxidase, and NADPH oxidases [10]. This oxidative burst activates NF-κB, amplifying inflammatory damage in vulnerable neuronal populations. Similar mechanisms operate in neurodegenerative diseases, where chronic oxidative stress and NF-κB activation drive neuroinflammation.

Pulmonary Diseases

Hyperoxic lung injury models demonstrate maturation-dependent NF-κB activation, with neonatal lungs showing preferential NF-κB activation upon hyperoxia exposure compared to adult lungs [8]. This differential response may contribute to developmental lung disorders such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting the ROS-NF-κB axis presents both opportunities and challenges for therapeutic development. Traditional antioxidant approaches have shown limited clinical success, likely due to non-specific actions and failure to address the nuanced role of ROS as signaling molecules [3]. More promising strategies include:

- Specific IKK inhibitors: Development of compounds that selectively target redox-sensitive IKK activation

- Nrf2 activators: Potentiation of endogenous antioxidant systems to indirectly modulate NF-κB

- Inhibitors of ROS-generating enzymes: Selective targeting of specific Nox isoforms

- Modulation of redox-sensitive phosphatases: Enhancing endogenous negative regulators of NF-κB signaling

Future research should focus on delineating cell-type-specific redox regulation of NF-κB, understanding temporal dynamics of pathway activation, and developing sophisticated delivery systems for tissue-specific targeting. The integration of systems biology approaches with single-cell technologies will further illuminate the complex interplay between oxidative stress and inflammation in human disease.

The activation of NF-κB by ROS constitutes a fundamental pro-inflammatory pathway with far-reaching implications for chronic disease pathogenesis. This whitepaper has detailed the molecular mechanisms, regulatory networks, experimental approaches, and pathophysiological significance of this critical signaling axis. The bidirectional nature of ROS-NF-κB interactions—with ROS both activating and being produced downstream of NF-κB—creates self-amplifying loops that sustain inflammatory responses in chronic diseases. Moving forward, sophisticated manipulation of this pathway, rather than blanket inhibition, holds promise for breaking the cycle of oxidative stress and inflammation in diverse pathological conditions.

The Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway is the principal cellular defense mechanism against oxidative and electrophilic stress [11] [12]. This system maintains cellular redox homeostasis by regulating the transcription of a broad network of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes [13] [14]. Under normal physiological conditions, the pathway ensures a finely-tuned, transient activation of Nrf2, preventing unnecessary antioxidant gene expression while maintaining readiness against oxidative insults [13]. However, dysregulation of this axis has been implicated in nearly all major human diseases, from neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases to diabetes and cancer, underscoring its critical role in the interplay between oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic disease pathogenesis [11] [15].

The molecular players in this pathway are precisely structured for their roles. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is a transcription factor belonging to the Cap'n'collar (CNC) basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family [14]. It is a modular protein composed of seven functional NRF2-ECH homology (Neh) domains [14]. The Neh2 domain contains DLG and ETGE motifs that facilitate binding to its negative regulator, KEAP1 [12] [14]. The Neh1 domain contains a CNC-bZIP DNA-binding motif that allows NRF2 to dimerize with small Maf proteins and bind to Antioxidant Response Elements (ARE) in DNA [12] [14]. The transactivation domains Neh3, Neh4, and Neh5 interact with coactivators, while Neh6 and Neh7 negatively regulate NRF2 through β-TrCP and RXRα interactions, respectively [14].

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) functions as the primary cellular sensor for oxidative and electrophilic stressors [12] [16]. This cysteine-rich, homodimeric protein contains five primary domains [16] [14]:

- BTB domain: Mediates KEAP1 homodimerization and binding to CUL3

- IVR domain: Rich in cysteine residues that function as stress sensors

- Kelch/DGR domain: Comprises six Kelch repeats that bind to the ETGE and DLG motifs of NRF2

- NTR and CTR domains: Flanking terminal regions

The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory mechanism of the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway under basal and stressed conditions:

Regulatory Mechanisms and Pathophysiological Roles

The Molecular Switch: From Basal Repression to Stress Activation

Under homeostatic conditions, KEAP1 forms part of a CUL3-RBX1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that tightly regulates NRF2 activity by targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation [12] [13]. The "hinge and latch" model explains this interaction: the KEAP1 homodimer binds NRF2 through two binding sites - a high-affinity ETGE motif (hinge) and a low-affinity DLG motif (latch) - creating a configuration that efficiently presents NRF2 for ubiquitination [12] [16].

During oxidative or electrophilic stress, specific cysteine residues in KEAP1 (notably Cys151 in the BTB domain and Cys273/Cys288 in the IVR domain) undergo modification [12] [16]. This induces conformational changes in KEAP1 that disrupt the "latch" interaction with the DLG motif while maintaining the "hinge" ETGE binding [16]. Consequently, NRF2 ubiquitination is impaired, leading to its stabilization and accumulation. Newly synthesized NRF2 escapes degradation, translocates to the nucleus, heterodimerizes with small Maf proteins, and binds to ARE/EpRE sequences in the promoter regions of target genes [12] [14].

The Double-Edged Sword: Protective versus Pathological Roles

The Nrf2-Keap1 axis exhibits a dual nature in human health and disease, functioning protectively in normal physiology but contributing to pathology when dysregulated.

Cytoprotective Roles: Under physiological conditions, transient NRF2 activation coordinates the expression of over 500 genes involved in cellular defense [15]. This includes antioxidants (SOD, catalase, GPx), glutathione synthesis and metabolism enzymes (GCLC, GCLM, GST), NADPH regeneration enzymes (G6PDH, 6PGD), and phase II detoxification enzymes (NQO1, HO-1) [12] [14] [15]. Through this extensive transcriptional program, NRF2 enhances cellular resilience against oxidative stress, reduces inflammation, and maintains redox homeostasis [11] [17].

Pathological Roles: Persistent NRF2 activation creates a environment conducive to tumorigenesis and therapy resistance [13] [16]. Cancer cells with constitutive NRF2 activation exhibit enhanced antioxidant capacity, metabolic reprogramming, chemoresistance, and immune evasion [18] [13] [14]. A 2025 study revealed that KEAP1 depletion or pharmacological inhibition diminishes PD-L1 expression across multiple cancer types, establishing the KEAP1/NRF2 axis as a novel mediator of this critical immune checkpoint protein [18]. This hyperactivation commonly results from somatic mutations in KEAP1, NRF2 (NFE2L2), or CUL3 genes, or from competitive inhibition of the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction by proteins like p62 [16] [19].

Table 1: NRF2 Target Genes and Their Protective Functions

| Gene Category | Representative Genes | Biological Function | Role in Disease Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant Enzymes | SOD, CAT, GPx, HO-1 | Direct neutralization of ROS | Reduces oxidative damage in neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases [15] |

| Glutathione Metabolism | GCLC, GCLM, GST, GR | Glutathione synthesis and recycling | Maintains cellular redox buffer; critical for detoxification [14] [15] |

| NADPH Regeneration | G6PDH, 6PGD, TKT, TAL | Pentose phosphate pathway enzymes | Provides reducing equivalents for antioxidant systems [14] |

| Detoxification Enzymes | NQO1, HO-1 | Phase II conjugation and elimination | Chemoprotection against carcinogens and toxins [12] [15] |

| Proteostasis | p62/SQSTM1 | Selective autophagy adapter | Clearance of damaged proteins and organelles [16] [19] |

Table 2: Disease Associations with Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway Dysregulation

| Disease Category | Specific Conditions | NRF2 Status | Molecular Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative | Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, ALS | Reduced activity | Increased oxidative damage, protein aggregation, neuronal death [17] [19] |

| Metabolic | Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome | Context-dependent | Insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, complications [14] |

| Cardiovascular | Atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart failure | Reduced activity | Endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, remodeling [11] [15] |

| Cancer | Lung, liver, thyroid, others | Frequently hyperactive | Metabolic reprogramming, chemoresistance, immune evasion [18] [16] [14] |

| Respiratory | COPD, asthma, fibrosis | Reduced activity | Chronic inflammation, tissue remodeling, oxidative damage [20] |

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

CRISPR Screening for Pathway Discovery

A 2025 study employed a powerful functional CRISPR gene knockout screening approach to identify druggable regulators of PD-L1 expression in the KEAP1/NRF2 axis [18]. The experimental workflow and key findings are summarized below:

Detailed Methodology:

Library Design: A custom-designed sgRNA library targeting approximately 1,400 "druggable" human genes (based on literature review and gene-drug interaction databases) with ~10,000 sgRNAs (7 sgRNAs/gene plus ~500 control sgRNAs) [18].

Cell Line Selection: Screening performed across 6 cancer lines - 3 ovarian (OVCAR4, CaOV3, SKOV3) and 3 pancreatic (MiaPaca2, ASPC1, KP4) - selected for robust PD-L1 induction in response to IFNγ [18].

Screening Execution: Cas9-expressing cells were lentivirally infected with the sgRNA library at low multiplicity of infection (MOI ≈ 0.25). After puromycin selection, cells were expanded to maintain ~500X coverage per sgRNA [18].

Sorting and Analysis: Following 15 days of expansion and 48 hours of IFNγ treatment, cells were fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) into PD-L1-high (top 25%) and PD-L1-low (bottom 25%) populations. Genomic DNA was isolated, sgRNA sequences amplified by PCR, and barcodes counted through next-generation sequencing (NGS) [18].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Differential enrichment of sgRNA barcodes and gene-level enrichment analysis in PD-L1-low versus high cells was assessed by beta-binomial modeling using the CB2 tool [18].

In Vivo and In Vitro Validation Approaches

In Vitro Models:

- Cell Culture Systems: SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells for neuronal studies, cultured in MEM/DMEM-F12 medium with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL) at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [19].

- Treatment Paradigms: Pb(C₂H₃O₂)₂ for lead exposure studies; N-acetylcysteine (antioxidant), Artemisitene (NRF2 activator), and Rapamycin (autophagy activator) for mechanistic interventions [19].

In Vivo Models:

- Animal Subjects: Four-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (98.31 ± 8.58 g) housed in specific pathogen-free conditions with 12-hour light-dark cycles [19].

- Exposure Protocol: Intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg Pb(C₂H₃O₂)₂ once daily, 5 days/week for 12 weeks to induce sub-chronic lead exposure [19].

- Behavioral Assessment: Morris water maze test to evaluate learning and spatial memory performance, including swimming distance, escape latency, and platform crossings [19].

- Tissue Analysis: Hippocampal morphology examination via hematoxylin-eosin and Nissl staining; Pb concentration measurement using ICP-MS after microwave-assisted acid digestion [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRF2 Activators | Sulforaphane, Dimethyl fumarate, Bardoxolone, Artemisitene | Induce nuclear translocation of NRF2 | React with KEAP1 cysteine residues to disrupt NRF2 ubiquitination [12] [19] |

| KEAP1 Inhibitors | KI-696, K67 | Block KEAP1-NRF2 protein-protein interaction | Directly target Kelch domain to prevent NRF2 binding and degradation [13] |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 KO, siRNA/shRNA, NRF2/KEAP1 expression vectors | Genetic manipulation of pathway components | Establish causal relationships in pathway regulation and function [18] |

| Antibodies | Anti-NRF2, Anti-KEAP1, Anti-HO-1, Anti-NQO1 | Western blot, IHC, immunofluorescence, ChIP | Detect protein expression, localization, and DNA binding [18] [19] |

| Reporters | ARE-luciferase constructs | Measure pathway activation | Quantify transcriptional activity in high-throughput screening [12] |

| Oxidative Stress Probes | DCFDA, MitoSOX, H2DCFDA | Measure ROS production | Assess functional consequences of pathway modulation [19] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway represents a compelling therapeutic target for a broad spectrum of human diseases. Pharmacological activation of NRF2 holds promise for conditions characterized by oxidative stress, including neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and inflammatory conditions [20] [17]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that NRF2 activators can provide neuroprotection, enhance mitochondrial function, and reduce inflammation [17] [19]. Conversely, NRF2 inhibitors are being explored for cancers with hyperactive NRF2 signaling, aiming to sensitize tumors to conventional therapies and overcome treatment resistance [13] [16].

Current research focuses on developing context-specific modulators that can precisely tune NRF2 activity without completely abrogating or constitutively activating the pathway. The integration of NRF2 modulators into precision medicine frameworks requires a deeper understanding of the heterogeneity of pathway activation across different disease states and genetic backgrounds [13]. Future studies must define biomarkers of NRF2 dependency, optimize therapeutic windows, and address long-term safety concerns associated with pharmacological NRF2 modulation [13]. As our knowledge of the complex regulatory networks surrounding the Nrf2-Keap1 axis continues to expand, so too will our ability to harness this fundamental pathway for therapeutic benefit across the spectrum of human disease.

The cellular response to stress is governed by sophisticated signaling networks, with the transcription factors Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) and Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) serving as master regulators of inflammation and oxidative stress responses, respectively. While NF-κB primarily controls the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, Nrf2 regulates a battery of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes. Historically studied in isolation, emerging evidence reveals these pathways are intricately linked through bidirectional cross-talk, forming a critical regulatory circuit that determines cellular fate in stress conditions. This antagonistic relationship represents a fundamental biological paradigm where inflammatory and antioxidant responses are reciprocally controlled. Understanding the molecular intricacies of this cross-talk is essential for elucidating the pathophysiology of chronic diseases and developing targeted therapeutic interventions for conditions where oxidative stress and inflammation coexist.

Molecular Mechanisms of Nrf2 and NF-κB Signaling

The Nrf2 Antioxidant Response Pathway

Nrf2 is a basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor that serves as the master regulator of cellular antioxidant defense. Under homeostatic conditions, Nrf2 is continuously ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome through its association with the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) repressor protein, which acts as a substrate adaptor for a Cullin 3 (Cul3)-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [21] [22]. Keap1 binds Nrf2 via a two-site mechanism ("hinge and latch" model) using DLG and ETGE motifs, maintaining Nrf2 at low basal levels with a short half-life of approximately 10-30 minutes [21].

Upon exposure to oxidative stress or electrophiles, specific cysteine sensors in Keap1 undergo modification, inducing conformational changes that disrupt its ability to target Nrf2 for degradation. Newly synthesized Nrf2 subsequently accumulates and translocates to the nucleus, where it forms heterodimers with small Maf proteins and binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) in the promoter regions of target genes [21] [23]. This activation cascade induces the expression of a extensive network of over 200 cytoprotective genes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic (GCLC) and modulatory (GCLM) subunits, which collectively enhance cellular resilience to oxidative damage [21] [23].

Table 1: Primary Nrf2 Target Genes and Their Cytoprotective Functions

| Gene | Protein | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|

| HMOX1 | Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1) | Heme catabolism, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 | Quinone detoxification, antioxidant |

| GCLC | Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase Catalytic Subunit | Glutathione biosynthesis |

| GCLM | Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase Modulatory Subunit | Glutathione biosynthesis |

| FTH1 | Ferritin Heavy Chain | Iron sequestration |

| TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin Reductase 1 | Redox regulation |

| SRXN1 | Sulfiredoxin | Antioxidant enzyme |

Beyond the canonical Keap1-dependent regulation, Nrf2 is also controlled through Keap1-independent mechanisms. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) can phosphorylate Nrf2, creating a recognition motif for β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), which serves as a substrate receptor for a Skp1-Cul1-Rbx1/Roc1 ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to Nrf2 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [21] [22]. Additionally, the autophagy adapter protein p62 can sequester Keap1 to autophagic degradation, resulting in Nrf2 activation, thereby creating a link between autophagy and the antioxidant response [21].

The NF-κB Inflammatory Signaling Pathway

NF-κB represents a family of inducible transcription factors that function as primary mediators of inflammatory and immune responses. The NF-κB family comprises five members: NF-κB1 (p50/p105), NF-κB2 (p52/p100), RelA (p65), RelB, and c-Rel, which form various homo- and heterodimers with distinct transcriptional activities [21] [7]. These proteins share a conserved Rel homology domain (RHD) responsible for DNA binding, dimerization, and nuclear localization. The most abundant and extensively studied dimer is the p65/p50 heterodimer, which exhibits strong transactivation potential [7].

NF-κB activation occurs through two principal signaling cascades: the canonical and non-canonical pathways. The canonical pathway is typically activated by pro-inflammatory stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). In resting cells, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory proteins of the IκB family, predominantly IκBα. Upon cellular stimulation, the IκB kinase (IKK) complex—composed of catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ and the regulatory subunit NEMO (IKKγ)—is activated and phosphorylates IκBα, leading to its K48-linked ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [21] [7]. This process liberates the NF-κB dimer, allowing its translocation to the nucleus where it binds to κB consensus sequences in target gene promoters and initiates transcription of inflammatory mediators.

Table 2: Major NF-κB Target Genes and Their Pro-inflammatory Functions

| Gene | Protein | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine |

| IL1B | Interleukin-1β | Pro-inflammatory cytokine |

| CXCL8 | Interleukin-8 | Neutrophil chemotaxis |

| ICAM1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 | Leukocyte adhesion |

| VCAM1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 | Leukocyte adhesion |

| COX2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 | Prostaglandin synthesis |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase | Nitric oxide production |

The non-canonical pathway, activated by specific stimuli such as CD40 ligand, B cell-activating factor (BAFF), and lymphotoxin-β, depends on NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)-mediated phosphorylation of IKKα, which subsequently phosphorylates the p100 precursor protein, leading to its partial proteasomal processing to mature p52. The resulting p52/RelB dimer then translocates to the nucleus to regulate genes involved in lymphoid organ development and B-cell maturation [22].

Molecular Cross-Talk: Mechanisms of Antagonistic Regulation

Nrf2-Mediated Suppression of NF-κB Signaling

The activation of the Nrf2 pathway results in potent suppression of NF-κB signaling through multiple interconnected mechanisms that ultimately restrain inflammatory responses:

Antioxidant-Mediated Indirect Inhibition: Nrf2 activation elevates the expression of a comprehensive network of antioxidant and detoxification enzymes, including HO-1, NQO1, and glutathione peroxidase, which collectively diminish cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [23] [24]. Since ROS function as critical secondary messengers in NF-κB activation by promoting IKK activity and IκBα degradation, this redox modulation creates an unfavorable environment for NF-κB signaling. Specifically, the Nrf2 target gene HO-1 catalyzes the degradation of heme into biliverdin (subsequently converted to bilirubin), carbon monoxide, and free iron, all of which possess anti-inflammatory properties [23]. Bilirubin and biliverdin exhibit potent antioxidant activity, while carbon monoxide modulates inflammatory responses through mitochondrial and signaling effects.

Direct Interference with NF-κB Activation: Nrf2 activation can impair IKKβ phosphorylation and subsequent IκBα degradation, thereby preventing NF-κB nuclear translocation [23]. Studies using Nrf2-deficient macrophages demonstrate enhanced IKKβ activity and increased phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα following inflammatory stimulation compared to wild-type cells [23]. Additionally, Nrf2 target genes such as GCLM and GCLC, which are essential for glutathione synthesis, contribute to maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, further inhibiting NF-κB activation.

Competition for Transcriptional Coactivators: Both Nrf2 and NF-κB require the CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300 complex as an essential transcriptional coactivator for efficient gene expression. These transcription factors compete for limited pools of CBP/p300 in the nucleus, establishing a molecular competition that can reciprocally regulate their transcriptional outputs [23]. Nrf2 interacts with CBP through its Neh4 and Neh5 domains, while NF-κB p65 subunit binds CBP when phosphorylated at Ser276. Overexpression of p65 can sequester CBP, limiting its availability for Nrf2 and thereby repressing ARE-mediated gene expression [23].

NF-κB-Mediated Repression of Nrf2 Signaling

The NF-κB pathway reciprocally inhibits Nrf2 signaling through several well-characterized mechanisms:

Cytokine-Mediated Suppression: NF-κB activation induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which can subsequently suppress Nrf2 signaling through various mechanisms. These cytokines can activate GSK-3β, which phosphorylates Nrf2, leading to its β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via the Keap1-independent pathway [21] [23]. This mechanism represents an indirect but potent means of Nrf2 suppression during inflammatory responses.

Transcriptional Coactivator Competition: As mentioned previously, the competition for CBP/p300 represents a pivotal mechanism of mutual repression. During robust inflammatory responses, activated NF-κB p65 subunits can effectively sequester limiting quantities of CBP/p300, thereby depriving Nrf2 of this essential coactivator and blunting the antioxidant response [23]. This competitive interplay creates a molecular switch that prioritizes inflammatory gene expression over antioxidant responses during acute stress.

Nuclear Keap1-Mediated Repression: NF-κB activation can influence the subcellular localization of Keap1, potentially promoting its nuclear translocation where it can directly interfere with Nrf2 transcriptional activity [23]. While Keap1 is predominantly cytoplasmic, studies have demonstrated that p65 overexpression can increase nuclear Keap1 levels, potentially through interactions with the nuclear import protein karyopherin alpha 6 (KPNA6). Nuclear Keap1 may subsequently repress Nrf2-ARE signaling through mechanisms that remain incompletely characterized but likely involve disruption of Nrf2-DNA binding or facilitation of nuclear Nrf2 degradation [23].

The intricate antagonistic relationship between NF-κB and Nrf2 is visually summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates the key molecular mechanisms of their bidirectional cross-talk.

Figure 1: Molecular Cross-Talk Between NF-κB and Nrf2 Signaling Pathways. The diagram illustrates the antagonistic regulation between these pathways, including competition for transcriptional coactivators (CBP/p300), antioxidant-mediated suppression of NF-κB, and cytokine-mediated inhibition of Nrf2.

Experimental Approaches for Studying NF-κB/Nrf2 Cross-Talk

In Vitro Methodologies

Cell Culture Models: The investigation of NF-κB/Nrf2 cross-talk employs various cellular models, including immortalized cell lines (HEK293T, BV-2 microglial cells, THP-1 monocyte/macrophages) and primary cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts - MEFs, primary peritoneal macrophages) [25] [26] [27]. THP-1 monocyte/macrophages are particularly valuable for inflammation studies and can be differentiated into macrophage-like cells using phorbol esters (e.g., PMA at 0.1 μM for 24 hours) [27]. Genetic manipulation through siRNA-mediated knockdown or CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing allows specific disruption of Nrf2, NF-κB components (p65, IKK subunits), or regulatory proteins (Keap1) to establish causal relationships in the cross-talk mechanisms [25] [26].

Stimulation and Inhibition Protocols: Inflammatory activation is typically induced using lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at concentrations ranging from 100-500 ng/mL for 6-24 hours [26] [27]. Oxidative stress can be triggered using compounds like tert-butyl hydroquinone (tBHQ) or sulforaphane (e.g., 14 μM for 6 hours), which modify Keap1 cysteine residues and activate Nrf2 [23] [26]. Specific pathway inhibitors include Bay 11-7082 (5-10 μM), which inhibits IκBα phosphorylation, and ML385, which directly blocks Nrf2 activity [27].

Luciferase Reporter Assays: Reporter constructs containing ARE or κB response elements upstream of a luciferase gene are transfected into cells to monitor pathway activity. For instance, the pHO1-15-LUC plasmid contains the HO-1 promoter with functional AREs, while κB-dependent reporters utilize multiple NF-κB binding sites [26]. Co-transfection with expression vectors for Nrf2, Keap1, p65, or dominant-negative mutants (e.g., ΔETGE-Nrf2, IκBS32A/S36A) enables mechanistic studies of pathway interactions [26].

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays investigate physical interactions between Nrf2, Keap1, p65, and CBP/p300. Cells are lysed in appropriate buffers (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors), and target proteins are immunoprecipitated using specific antibodies, followed by Western blotting to detect associated proteins [26]. GST pulldown assays using recombinant GST-tagged proteins (e.g., GST-PAK1 for RAC1 activation studies) further characterize direct molecular interactions [26].

In Vivo Models

Genetic Mouse Models: Tissue-specific knockout mice generated using Cre-loxP technology provide powerful tools for investigating cell-type-specific functions of NF-κB and Nrf2. For example, hepatocyte-specific Nrf2/p65 double knockout mice have revealed spontaneous liver inflammation and necrosis when both transcription factors are absent, along with complex interactions in hepatocyte proliferation control [25]. Nrf2 knockout mice generally exhibit heightened sensitivity to inflammatory stimuli and increased NF-κB activation in various injury models [23].

Disease Induction Models: Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury models demonstrate the functional consequences of NF-κB/Nrf2 cross-talk, with Nrf2 deficiency impairing hepatocyte proliferation under homeostatic conditions and after acute injury [25]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced systemic inflammation models reveal exaggerated cytokine production and NF-κB activation in Nrf2-deficient animals [23]. Macrophage depletion studies using clodronate liposomes have established the non-cell-autonomous mechanisms through which Nrf2/p65 cross-talk controls hepatocyte proliferation via macrophage accumulation [25].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying NF-κB/Nrf2 Cross-Talk

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | THP-1 monocytes, BV-2 microglia, MEFs | In vitro modeling of immune and inflammatory responses |

| Activators | LPS (100-500 ng/mL), TNF-α (10-50 ng/mL) | NF-κB pathway induction |

| Activators | Sulforaphane (5-20 μM), tBHQ (10-50 μM) | Nrf2 pathway induction |

| Inhibitors | Bay 11-7082 (5-10 μM), SC-514 | IKK/NF-κB pathway inhibition |

| Inhibitors | ML385, Brusatol | Nrf2 pathway inhibition |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA against p65/Nrf2, CRISPR-Cas9 | Gene-specific knockdown/knockout |

| Reporter Plasmids | ARE-luciferase, κB-luciferase | Pathway activity measurement |

| Antibodies | Anti-p65, anti-Nrf2, anti-IκBα, anti-HO-1 | Protein detection by Western/IF/IHC |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Role in Chronic Disease Pathogenesis

The dysregulation of NF-κB/Nrf2 cross-talk contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of numerous chronic conditions:

Neurodegenerative Disorders: In neurological conditions, Nrf2 deficiency exacerbates NF-κB activity, leading to augmented cytokine production that contributes to astrogliosis, neuronal death, and demyelination [23]. Nrf2 knockout mice display heightened sensitivity to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, while Nrf2 activators demonstrate protective effects in models of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease [23].

Cardiovascular Diseases: In coronary artery disease, oxidative stress and inflammation drive disease progression through reciprocal NF-κB activation and Nrf2 repression [24]. Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and Nrf2 repression have been documented in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with stable coronary artery disease, while Nrf2 activation protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury and delays progression to heart failure [24].

COVID-19 Pathogenesis: Severe COVID-19 is characterized by NF-κB-mediated cytokine storm coupled with suppression of the Nrf2 pathway, creating a deleterious imbalance that amplifies tissue damage [28]. Transcriptomic analyses of COVID-19 patients reveal upregulated NF-κB signaling genes alongside suppression of Nrf2 antioxidant response genes, potentially contributing to neurological complications observed in severe infections [28].

Metabolic and Inflammatory Conditions: The NF-κB/Nrf2 imbalance manifests in various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and lupus nephritis, where exaggerated NF-κB signaling drives pathology while impaired Nrf2 activity fails to provide adequate counter-regulation [23].

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting NF-κB/Nrf2 Cross-Talk

Several therapeutic approaches aim to restore balance to the NF-κB/Nrf2 axis:

Nrf2 Activators: Sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables, and synthetic triterpenoids like CDDO-Im potently activate Nrf2 by modifying Keap1 cysteine residues, resulting in enhanced antioxidant gene expression and concomitant NF-κB suppression [23]. These compounds demonstrate efficacy in preclinical models of inflammation, neurodegeneration, and metabolic disorders.

NF-κB Inhibitors: Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., bortezomib) prevent IκB degradation, thereby maintaining NF-κB in an inactive cytoplasmic complex [7]. IKK-specific inhibitors (e.g., SPC-839, BMS-345541) directly target the kinase complex responsible for NF-κB activation, while monoclonal antibodies against pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., anti-TNF-α) interrupt positive feedback loops that sustain NF-κB signaling [7].

Dual-Targeting Approaches: Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid, exemplifies natural products with dual activity, simultaneously inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation while activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thereby ameliorating both inflammatory and oxidative stress components in cellular models [27]. Similarly, the sirtuin SIRT6 has emerged as a regulatory node that activates Nrf2 through Keap1 inhibition while suppressing NF-κB signaling, producing coordinated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [24].

Novel Therapeutic Strategies: Emerging approaches include non-coding RNA-based therapies that simultaneously modulate both pathways, CAR-T cell therapies engineered to target inflammatory disease components, and combination therapies that strategically engage both pathways to restore redox and inflammatory homeostasis [7].

Concluding Perspectives

The antagonistic cross-talk between NF-κB and Nrf2 represents a fundamental biological paradigm that integrates cellular responses to inflammatory and oxidative stresses. The molecular mechanisms underlying this reciprocal regulation—including competition for transcriptional coactivators, pathway-specific post-translational modifications, and redox-mediated feedback loops—create a sophisticated control system that determines cellular fate under stress conditions. Understanding these interactions provides critical insights into the pathogenesis of chronic diseases characterized by concurrent inflammation and oxidative damage. Future research should focus on elucidating tissue-specific variations in this cross-talk, temporal aspects of pathway interactions, and developing therapeutic strategies that effectively restore balance to this critical regulatory axis for treating complex chronic diseases.

Oxidative Stress as a Common Denominator in Age-Related Diseases and Cancer

Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses, is a fundamental pathological mechanism underpinning both aging and carcinogenesis. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on the role of oxidative stress as a key mediator connecting physiological aging with age-related diseases and cancer. We detail the molecular pathways through which oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA drives cellular senescence, chronic inflammation, and malignant transformation. The document provides a comprehensive analysis of validated oxidative stress biomarkers, standardized methodologies for their quantification, and visualization of critical signaling pathways. Furthermore, we explore the therapeutic implications of targeting oxidative stress pathways, highlighting both challenges and opportunities for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of redox biology and chronic disease.

The free radical theory of aging, first proposed by Denham Harman in 1956, posits that the cumulative damage inflicted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) throughout an organism's lifespan drives the functional declines characteristic of aging [29]. This theory has since evolved into the more nuanced oxidative stress theory of aging, which incorporates our modern understanding of redox signaling and antioxidant defense systems [30]. Oxidative stress results when the critical balance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant molecules shifts toward the former, leading to disruptive oxidation of cellular macromolecules and altered signal transduction [29].

Aging constitutes a progressive loss of tissue and organ function over time, with oxidative stress representing a core mechanism underlying age-associated functional declines [30]. The close relationship between oxidative stress, inflammation, and aging has led to the formulation of the "oxi-inflamm-aging" theory, which describes a vicious cycle wherein chronic oxidative stress particularly affects regulatory systems (nervous, endocrine, and immune), triggering inflammatory responses that further exacerbate oxidative damage [30]. This framework establishes oxidative stress as a common biological platform linking fundamental aging processes with multiple pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disorders, metabolic diseases, and various cancers [31].

In the context of cancer, oxidative stress demonstrates a dual nature. While excessive ROS can cause irreversible damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, promoting genomic instability and carcinogenesis, cancer cells also exploit ROS at moderate levels to drive proliferative signaling and survival pathways [32]. This paradoxical relationship establishes oxidative stress as a significant factor across the entire cancer continuum, from initiation and promotion to progression and metastasis.

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathophysiological Pathways

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) originate from both endogenous and exogenous sources. Endogenous production occurs primarily through:

- Mitochondrial electron transport: Electron leakage during oxidative phosphorylation generates superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), particularly at complexes I and III of the electron transport chain [29].

- NADPH oxidases (NOX): Membrane-associated enzymes that catalyze the production of superoxide anion by transferring electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen [30].

- Other enzymatic systems: Xanthine oxidase, uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and reactions involving cytochrome P450 enzymes, lipoxygenase, and cyclooxygenase [32].

Exogenous RONS sources include ionizing radiation, environmental pollutants, tobacco smoke, certain pharmaceuticals (e.g., cyclosporine, tacrolimus), and industrial chemicals [30]. These exogenous stressors amplify the endogenous oxidative burden, accelerating cellular damage.

The superoxide anion undergoes dismutation by superoxide dismutase (SOD) to form hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which is more stable and membrane-permeable. Through Fenton or Haber–Weiss reactions, H₂O₂ can be converted to the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (OH•), which reacts indiscriminately with cellular components [30]. Simultaneously, nitric oxide (NO) produced by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms can react with superoxide to form peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), a potent nitrating agent that contributes to nitrosative stress [30].

Oxidative Damage to Cellular Macromolecules

RONS, whether endogenous or exogenous, cause oxidative modifications to all major cellular macromolecules, which can serve as biomarkers of oxidative stress [30].

Lipid Peroxidation

Poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes are particularly vulnerable to oxidation by hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals [30]. This peroxidation generates reactive aldehydes including:

- Malondialdehyde (MDA)

- 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE)

- Isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs)

These lipid peroxidation products can further damage proteins and DNA, and are implicated in various pathological processes including atherosclerosis and inflammation [30].

Protein Modification

Oxidative protein modifications include:

- Protein carbonyls (PC): Formed by Fenton reaction of oxidants with lysine, arginine, proline, and threonine residues, or via binding of aldehydic lipid oxidation products (Michael-addition reactions) [30].

- Nitrotyrosine (NT): Generated through reactions between reactive nitrogen species and tyrosine residues [33].

- Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs): Result from non-enzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and amino groups of proteins, particularly enhanced under hyperglycemic conditions [33].

DNA Oxidation

Oxidative damage to DNA results in mutagenic lesions including:

- 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-guanine (8-oxoGuo)

- 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG)

- Various base modifications (2-hydroxy adenine, 8-oxoadenine, 5-hydroxycytosine)

8-oxoGuo represents a highly mutagenic lesion that can result in G-to-T transversion events, contributing to carcinogenesis [30].

Antioxidant Defense Systems

Biological systems employ sophisticated antioxidant defenses comprising both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components:

- Primary antioxidant enzymes: Superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyzes the conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide; catalase (CAT) decomposes hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen; glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) reduces peroxides and hydroxyl radicals using reduced glutathione (GSH) as a substrate [30].

- Other antioxidant enzymes: Glutathione-S-transferase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase provide additional protective capacity [30].

- Non-enzymatic antioxidants: Include bilirubin, α-tocopherol (vitamin E), β-carotene, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), albumin, uric acid, glutathione, and phenolic compounds such as resveratrol [30] [32].

The delicate balance between ROS production and these antioxidant defenses determines the cellular redox state, with disruption of this equilibrium leading to oxidative stress and its pathological consequences.

Signaling Pathways Linking Oxidative Stress with Aging and Cancer

Oxidative Stress-Induced Cellular Senescence

Cellular senescence represents a state of irreversible growth arrest triggered by various stressors, including oxidative damage. Senescent cells acquire a distinctive secretory phenotype known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), characterized by secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases [30]. RONS induce cellular senescence through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

- mTOR pathway regulation: Oxidative stress modulates mammalian target of rapamycin complexes, influencing cellular growth and metabolism [30].

- FOXO protein inhibition: RONS inhibit FOXO transcription factors, which are involved in insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1-mediated protection from oxidative stress [30].

- Sirtuin activity reduction: Oxidative stress suppresses sirtuins, histone deacetylases that regulate stress response and longevity pathways, leading to increased ROS production and inflammation [30].

- Cell cycle regulation: RONS activate the p16INK4a/pRB and p53/p21 pathways, establishing and maintaining senescence-associated growth arrest [30].

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways through which oxidative stress induces cellular senescence:

Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis

The role of oxidative stress in cancer is complex and context-dependent, contributing to both tumor initiation and progression through several mechanisms:

- Genomic instability: ROS-induced DNA damage creates mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, initiating malignant transformation [32].

- Signal transduction activation: Moderate ROS levels activate growth-promoting signaling pathways including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and NF-κB, driving cellular proliferation and survival [32].

- Hypoxia response: ROS stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), promoting angiogenesis and metabolic adaptation in tumors [32].

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): Oxidative stress promotes EMT, enhancing invasive and metastatic potential [30].

Cancer cells typically exhibit elevated basal ROS levels compared to normal cells, creating a dependency on adaptive antioxidant responses. This vulnerability can be therapeutically exploited through ROS-inducing agents or inhibition of antioxidant systems in cancer cells.

The Oxidation-Inflammation Circuit in Chronic Disease

The interplay between oxidative stress and inflammation creates a self-amplifying cycle that drives the pathogenesis of numerous age-related conditions. This "oxi-inflamm-aging" circuit operates through several mechanisms:

- NF-κB activation: ROS activate the NF-κB pathway, a master regulator of inflammatory gene expression, leading to production of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) that further stimulate ROS production [30] [34].

- NLRP3 inflammasome activation: Oxidative stress triggers assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in caspase-1 activation and maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [34].

- Immune cell infiltration: Inflammatory mediators recruit immune cells that produce additional ROS and RNS, perpetuating the cycle [35].

This oxidation-inflammation connection is particularly evident in diabetic vascular complications, where hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and chronic inflammation synergistically drive both microvascular and macrovascular pathology [34].

Quantitative Biomarker Analysis and Methodologies

Established Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

Reliable quantification of oxidative stress biomarkers is essential for both research and clinical applications. The table below summarizes key biomarkers, their analytical methods, and disease associations:

Table 1: Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Detection Methodologies

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarker | Detection Methods | Clinical/Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Peroxidation | Malondialdehyde (MDA) | TBARS assay, HPLC | Cardiovascular disease, cancer, aging [30] |

| 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) | Immunohistochemistry, GC-MS | Neurodegenerative diseases, atherosclerosis [30] | |

| F2-Isoprostanes | GC-MS, ELISA | Oxidative stress status in various diseases [30] | |

| Protein Oxidation | Protein Carbonyls (PC) | DNPH derivatization, Western blot, ELISA | Aging, neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, HIV [30] [33] |

| Nitrotyrosine (NT) | Immunohistochemistry, ELISA | Inflammatory conditions, cardiovascular diseases [30] | |

| Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) | ELISA, HPLC, skin autofluorescence | Diabetes, renal failure, Alzheimer's disease [33] | |

| DNA Oxidation | 8-OHdG/8-oxodG | HPLC-EC, ELISA, LC-MS/MS | Cancer, aging, neurodegenerative disorders [30] [36] |

| Antioxidant Capacity | SOD, CAT, GPx activity | Spectrophotometric assays | Various chronic diseases, aging [30] |

| Glutathione (GSH/GSSG) | HPLC, enzymatic recycling assay | Oxidative stress status across pathologies [32] |

Methodological Protocols for Key Biomarkers

Protein Carbonyl Detection via ELISA

Principle: Protein carbonyl groups are derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), forming stable dinitrophenylhydrazone adducts detected by anti-DNP antibodies.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate proteins from tissue homogenate or plasma via precipitation with 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

- Derivatization: React protein pellet with 10mM DNPH in 2M HCl for 60 minutes at room temperature in the dark

- Washing: Remove excess DNPH by repeated TCA precipitation and washing with ethanol:ethyl acetate (1:1)

- Protein Resuspension: Dissolve final pellet in 6M guanidine hydrochloride