The Unseen Gatekeeper

What Muscle Biopsies Reveal About Our Ability to Swallow

The silent struggle of a simple sip

We do it thousands of times a day without a second thought: swallowing. It's a seamless ballet of nerves and muscles, a reflex so ingrained we only notice it when it fails. For millions, that failure is a daily reality—a condition known as dysphagia, where a sip of water can feel like a challenge and a meal a perilous journey . At the heart of this struggle often lies a tiny, ring-shaped muscle you've probably never heard of: the cricopharyngeus muscle. For decades, it was a medical black box. Why does this crucial muscle sometimes malfunction, turning from a gatekeeper into a gateblocker? The answers, scientists discovered, were hidden in its microscopic architecture, revealed through the powerful lens of histopathology—the study of diseased tissue .

This is the story of how peering through a microscope at stained slivers of muscle is revolutionizing our understanding of a common and debilitating human condition.

The Anatomical Gatekeeper: Meet the CP Muscle

Imagine a sophisticated, one-way valve at the very top of your esophagus (the food pipe). That's the cricopharyngeus (CP) muscle. It's part of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), and its job is deceptively simple:

At Rest

It remains tightly closed, creating a constant pressure. This brilliant design prevents us from inhaling air into our stomachs with every breath and, more importantly, stops acidic stomach contents from refluxing up into our throats .

During Swallow

For less than a second, it receives a precise neurological command to relax and open, allowing the food or liquid bolus to pass smoothly into the esophagus. It then snaps shut again .

Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction

When this "relax-and-open" sequence fails, it's called Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction. The result? A feeling of a lump in the throat, choking, and the dangerous aspiration of food or drink into the lungs .

Theories of Dysfunction: Spasm or Weakness?

For a long time, the prevailing theory was that dysphagia was caused by the CP muscle being too tight—a hypertonic spasm that refused to open. Treatment, therefore, focused on relaxing or cutting the muscle. But this didn't always work. A new question emerged: What if the problem wasn't that the muscle was too tight, but that it was structurally incompetent? What if the muscle fibers themselves were being replaced by something else?

This is where histopathology entered the stage, shifting the investigation from the macro to the micro level.

A Microscopic Detective Story: The Key Experiment

To solve the mystery, researchers designed a crucial study comparing the CP muscle of patients with dysphagia to that of healthy controls .

Methodology: From Surgery to Slide

The process was meticulous and ethical, following strict protocols:

Patient Selection

Two groups were formed. The Dysphagia Group consisted of patients with severe, clinically confirmed cricopharyngeal dysfunction. The Control Group consisted of individuals who had passed away from causes unrelated to swallowing, with no history of dysphagia .

Biopsy Collection

During a surgical procedure called a cricopharyngeal myotomy (where the muscle is cut to relieve symptoms), a small, pea-sized biopsy of the CP muscle was taken from the dysphagia patients. Similar samples were collected post-mortem from the control group .

Tissue Processing

The muscle samples were preserved, dehydrated, and embedded in a hard paraffin wax block to be sliced into incredibly thin sections—thinner than a human hair .

Staining

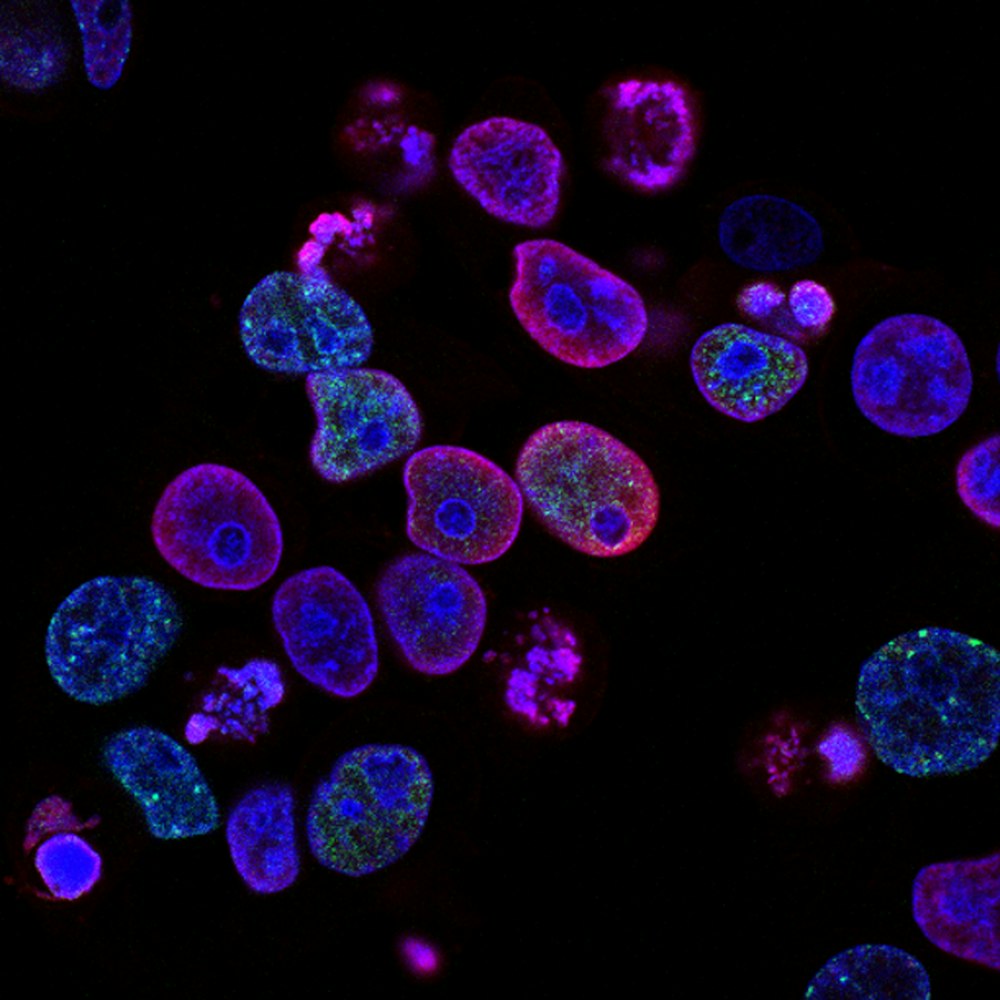

The sections were mounted on glass slides and stained with special dyes. Two stains were critical:

- Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E): A general stain that shows overall cell structure, highlighting muscle fibers (pink) and cell nuclei (blue) .

- Masson's Trichrome: A special stain that colors muscle fibers red and, crucially, collagen (scar tissue) a bright blue .

Results and Analysis: A Landscape Transformed

Under the microscope, the difference between the healthy and diseased tissue was stark and revealing .

The Healthy CP Muscle

Showed a clean, organized structure of tightly packed, parallel muscle fibers with very little blue-staining collagen between them .

The Diseased CP Muscle

Told a different story. The landscape was chaotic. The normal muscle fibers were fragmented, atrophied (shrunken), and, most significantly, widely separated by large amounts of blue-staining collagenous tissue—a condition known as fibrosis .

Paradigm Shift

This finding was a paradigm shift. The problem wasn't just a "spasm"; it was a fundamental structural degeneration. The muscle was being turned into non-functional scar tissue, losing its elasticity and its ability to generate a coordinated, timely relaxation. It was becoming a stiff, unyielding scar band .

The Data: Quantifying the Damage

The visual findings were compelling, but researchers quantified them to remove all doubt .

| Group | Average Muscle Fiber Diameter (micrometers) |

|---|---|

| Control (Healthy) | 45.2 ± 5.1 |

| Dysphagia Patients | 28.7 ± 6.3 |

| Group | Average Fibrosis (%) |

|---|---|

| Control (Healthy) | 8.5 ± 2.1 |

| Dysphagia Patients | 34.8 ± 9.7 |

| Pathological Feature | Control Group (incidence) | Dysphagia Group (incidence) |

|---|---|---|

| Ragged Red Fibers (mitochondrial issues) | 5% | 55% |

| Internalized Nuclei | 10% | 75% |

| Moth-Eaten Fibers (degeneration) | 2% | 60% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Decoding the Muscle

Here are the key tools and reagents that made this microscopic detective work possible .

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Formalin Solution | A preservative (fixative) that "locks" the tissue structure in place, preventing decay and decomposition . |

| Paraffin Wax | Used to embed the fixed tissue, providing a solid medium that allows for precise, ultra-thin slicing by a microtome . |

| Haematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) Stain | The workhorse of histology. Haematoxylin stains nuclei blue, and Eosin stains cytoplasm and muscle fibers pink, providing a basic cellular map . |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | The key diagnostic tool. It differentially stains muscle fibers (red) and collagen fibrosis (blue), making the central pathology of the disease visible . |

| Light Microscope | The primary instrument for viewing the stained tissue sections, magnifying them hundreds of times to reveal cellular and structural details . |

Conclusion: A New View on an Old Problem

The histopathological study of the cricopharyngeus muscle has been transformative. By looking beyond the spasm and into the muscle's very fabric, scientists uncovered a story of fibrosis and degeneration . This evidence has fundamentally changed our understanding of cricopharyngeal dysfunction—it's not always a muscle that won't open, but often a muscle that can't open properly because it has been replaced by scar tissue .

This knowledge directly influences treatment. It helps explain why a simple muscle relaxant may not work and strengthens the case for interventions like myotomy, which physically cuts the stiff, fibrotic band . Furthermore, it opens new avenues for research: What causes this fibrosis? Is it aging, chronic acid reflux, or neurological insults? Future studies will continue to use the powerful tools of histopathology to find the triggers, hoping to move from cutting the problem to preventing it altogether, ensuring that the simple, vital act of swallowing remains the effortless reflex it was meant to be .