Transcription Factors as Inflammatory Markers: A Comparative Analysis of NF-κB, STAT, and IRF in Disease and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of key inflammatory transcription factors—NF-κB, STAT, and IRF—as biomarkers in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Transcription Factors as Inflammatory Markers: A Comparative Analysis of NF-κB, STAT, and IRF in Disease and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of key inflammatory transcription factors—NF-κB, STAT, and IRF—as biomarkers in biomedical research and therapeutic development. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational biology, distinct activation pathways, and specific roles of these factors in chronic diseases, including metabolic syndrome, cancer, and renal aging. The content details state-of-the-art methodological approaches for their quantification in research and potential clinical settings, addressing common technical challenges and optimization strategies. A critical validation framework compares their specificity, predictive power, and clinical utility against traditional inflammatory markers like cytokines and acute-phase proteins. By synthesizing evidence across disease contexts, this review aims to guide the selection and application of these central regulatory molecules as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring therapeutic efficacy.

The Core Inflammatory Trio: Foundational Biology of NF-κB, STAT, and IRF Transcription Factors

The inflammatory response is a complex biological process that requires the rapid and coordinated activation of a specific transcriptional program, controlling the expression of hundreds of genes in a cell-type and stimulus-specific manner [1]. At the heart of this process are signal-regulated transcription factors (SRTFs), which sit at the receiving end of pathways originating from pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors [2]. These factors are activated by inflammatory stimuli and interact with a genome that has been pre-configured by lineage-determining transcription factors (LDTFs) to enable a tailored immune response [2]. The major SRTF families involved in inflammation include NF-κB, STATs, IRFs, and AP-1 [1] [3]. Their activity is essential for sensing environmental changes, mounting a defense against microbes, and initiating tissue repair, but their dysregulation can lead to chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer [1] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Major SRTF Families

The table below provides a detailed comparison of the primary SRTF families, highlighting their distinct activation mechanisms, DNA binding motifs, and key functions in inflammation.

| Transcription Factor Family | Key Members | Activation Mechanism & Signaling Pathways | DNA Binding Motif | Primary Roles in Inflammation | Associated Inflammatory Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB [3] | p50, p52, p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel [3] | Activated via canonical (IKKβ/IκB degradation) or non-canonical (IKKα/p100 processing) pathways by PAMPs, DAMPs, and cytokines like TNF [3]. | 5'-GGGRNWYYCC-3' (κB site) [2] | Master regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression; roles in innate & adaptive immunity [3]. | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), Multiple Sclerosis (MS) [3]. |

| STAT [3] | STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6 [3] | Phosphorylated by JAK kinases upon cytokine receptor engagement (e.g., IFNs, ILs); form homo-/heterodimers [3]. | GAS (Gamma-activated site): TTCN3-4GAA [2] | IFN signaling (STAT1/2), innate immunity & cell metabolism (STAT3), T-cell differentiation (STAT4), immune cell development (STAT5), antibody production (STAT6) [3]. | Rheumatoid Arthritis, immuno-inflammatory conditions [3]. |

| IRF [2] [3] | IRF1 - IRF9 [2] | Activated downstream of PRRs (e.g., TLR3, TLR4); key inducers of type I interferon responses [1] [2]. | IRF-E: 5'-GAAA-3' / ISRE: 5'-PuPuAAANNGAAAPyPy-3' [2] | Regulation of type I IFN genes and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs); antiviral defense [2]. | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) [3]. |

| AP-1 [1] | Fos, Jun, ATF subunits [1] | Activated by a variety of inflammatory stimuli, including microbial products and cytokines [1]. | Information missing | Regulates genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses; often cooperates with other TFs [1]. | Information missing |

Experimental Protocols for Studying SRTFs

Genomic Profiling of Inflammatory Gene Expression (RNA-seq)

This protocol is used to define the gene expression cascade induced by inflammatory stimuli at high resolution [1].

- 1. Cell Stimulation: Treat primary immune cells (e.g., mouse macrophages or dendritic cells) with an inflammatory agonist such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for a time course (e.g., from 0 to 2 hours) [1].

- 2. RNA Extraction: Harvest cells at each time point and isolate total RNA.

- 3. Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from either mature, polyadenylated mRNA to assess translatable transcripts, or from nascent transcripts using metabolic labeling or genome-wide nuclear run-on (GRO-seq) to directly monitor transcriptional activity [1].

- 4. Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads to the genome and quantify gene expression. Cluster genes based on temporal kinetics and analyze overrepresented transcription-factor-binding motifs in promoters of co-regulated genes [1].

Mapping Transcription Factor Binding (ChIP-seq)

This protocol identifies genome-wide binding sites for SRTFs, helping to define their direct transcriptional targets [4].

- 1. Cross-Linking: Formaldehyde is used to crosslink proteins to DNA in cells following inflammatory stimulation.

- 2. Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and fragment chromatin via sonication into small pieces.

- 3. Immunoprecipitation: Use an antibody specific to the transcription factor of interest (e.g., against STAT1 or p65) to pull down the protein-DNA complexes.

- 4. Library Preparation and Sequencing: Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and prepare libraries for high-throughput sequencing [4].

- 5. Data Analysis: Sequence reads are aligned to the reference genome to identify peaks of TF enrichment. De novo motif discovery tools like MEME can be applied to the top 500 strongest peaks to identify the bound DNA motif [4].

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

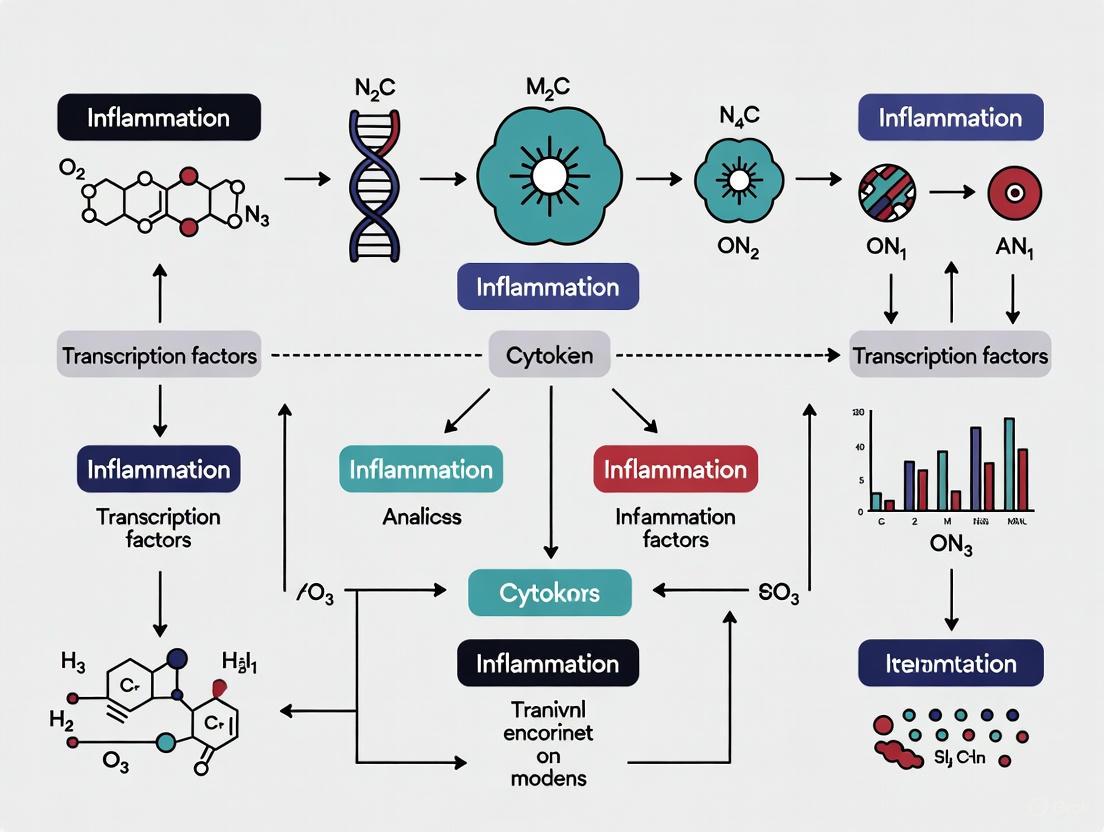

The following diagrams illustrate the core signaling pathways and regulatory logic of major SRTFs in inflammation.

NF-κB and STAT Signaling Pathways

Integrative Regulatory Logic of SRTFs

The table below lists key reagents, datasets, and computational tools essential for experimental research on SRTFs in inflammation.

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in SRTF Research | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | Experimental Protocol | Maps genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors to identify direct target genes [1] [4]. | ENCODE Project [4] |

| RNA-seq / GRO-seq | Experimental Protocol | Profiles transcriptome changes in response to inflammation; GRO-seq specifically captures nascent transcription for kinetic studies [1]. | - |

| Olink Target 96 Inflammation Panel | Proteomic Assay | Quantifies 92 immune-related proteins from plasma with high sensitivity, useful for identifying inflammatory signatures linked to SRTF activity [5]. | - |

| Factorbook | Computational Database | Catalogs TF motifs, binding sites, and annotations from ENCODE ChIP-seq and HT-SELEX data for motif analysis and binding site prediction [4]. | www.factorbook.org |

| scCube | Computational Tool (Python) | Simulates spatially resolved transcriptomics data, enabling benchmarking of computational methods for analyzing gene expression in a spatial context [6]. | GitHub: ZJUFanLab/scCube |

| HT-SELEX | Experimental Protocol | Systematically determines the in vitro DNA binding specificity of transcription factors [4]. | - |

Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) represents a family of structurally related transcription factors that function as pivotal regulators of immune and inflammatory responses. Since its initial discovery in 1986 as a nuclear factor binding to the kappa enhancer in B cells, NF-κB has been established as a critical mediator in numerous cellular processes including immunity, inflammation, cell survival, and proliferation [7]. The NF-κB signaling system is a highly dynamic protein interaction network that integrates information from various environmental cues to determine appropriate cellular responses, particularly in immune cells such as T lymphocytes [8]. Dysregulation of NF-κB activation contributes to a diverse spectrum of diseases, including chronic inflammatory disorders, autoimmune diseases, and cancer, making it a significant therapeutic target in drug development [7] [9].

This comparative guide provides a structured analysis of the two principal NF-κB activation pathways—canonical and non-canonical—focusing on their structural components, activation mechanisms, kinetic profiles, and functional outputs. Within the broader context of transcription factor research as inflammatory markers, understanding the distinct and overlapping features of these pathways is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that can modulate specific aspects of the immune response without completely abrogating host defense mechanisms.

Structural Composition of NF-κB System

NF-κB Transcription Factor Family

The mammalian NF-κB transcription factor family comprises five members that can form various homo- and heterodimers:

- RELA (p65): Contains a transactivation domain (TAD) and is a major component of the canonical pathway.

- c-REL (c-Rel): Also possesses a TAD and participates primarily in canonical signaling.

- RELB (RelB): Contains a TAD and functions mainly in the non-canonical pathway.

- NFKB1 (p105/p50): The p105 precursor is processed to p50, which lacks a TAD and functions as a transcriptional repressor when homodimerized.

- NFKB2 (p100/p52): The p100 precursor is processed to p52, which also lacks a TAD [7] [10].

All five members share a conserved N-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD) that mediates dimerization, nuclear localization, DNA binding, and interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins [8] [9]. The most prevalent NF-κB dimer activated through the canonical pathway is the p50-RelA heterodimer, while the non-canonical pathway typically generates p52-RelB heterodimers [10].

IκB Inhibitory Proteins

The IκB (Inhibitor of κB) family proteins maintain NF-κB in an inactive state in the cytoplasm by masking its nuclear localization signals. This family includes:

- Classical IκBs: IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε, which are present in the cytoplasm of resting cells and undergo stimulus-induced degradation [7].

- Precursor proteins: p105 (processing yields p50) and p100 (processing yields p52), which also contain C-terminal ankyrin repeat domains that function as IκB-like inhibitory regions [10] [11].

- Atypical IκBs: IκBζ, BCL-3, and IκBNS, which are synthesized upon cell activation and primarily function in the nucleus to modulate transcriptional activity [7].

These inhibitory proteins characterize through 3-8 ankyrin repeats at their C-termini that mediate binding to the RHD of NF-κB dimers, while their N-terminal contain phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites that participate in signal-responsive degradation [7].

IKK Complex Components

The IκB kinase (IKK) complex serves as the central regulator of NF-κB activation and consists of:

- IKKα: A catalytic subunit involved in both canonical and non-canonical pathways, with predominant function in the non-canonical pathway.

- IKKβ: A catalytic subunit primarily responsible for canonical pathway activation.

- NEMO/IKKγ: A regulatory subunit essential for canonical signaling but not required for the non-canonical pathway [12] [13].

Both IKKα and IKKβ share approximately 50% sequence identity and contain an N-terminal kinase domain, a helix-loop-helix motif, and a leucine zipper domain that facilitates dimerization [12]. The interaction between the kinase subunits and NEMO occurs through a small peptide at the carboxyl terminus of IKKα and IKKβ [12].

Table 1: Structural Components of the NF-κB Signaling System

| Component Type | Member | Key Structural Features | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB Subunits | RELA (p65) | RHD + TAD | Canonical pathway transactivation |

| c-REL (c-Rel) | RHD + TAD | Canonical pathway transactivation | |

| RELB (RelB) | RHD + TAD | Non-canonical pathway transactivation | |

| NFKB1 (p50) | RHD only (from p105 processing) | DNA binding, transcriptional repression/activation | |

| NFKB2 (p52) | RHD only (from p100 processing) | DNA binding, transcriptional repression/activation | |

| IκB Inhibitors | IκBα | 6 ankyrin repeats | Cytoplasmic sequestration of NF-κB |

| p100/p105 | RHD + ankyrin repeats | Precursor proteins with autoinhibitory function | |

| BCL-3 | Nuclear IκB with transactivation capability | Nuclear regulator of p50/p52 homodimers | |

| IKK Complex | IKKα | Kinase domain, LZ, HLH, NBD | Phosphorylates IκB and p100 |

| IKKβ | Kinase domain, LZ, HLH, NBD | Phosphorylates IκB in canonical pathway | |

| NEMO/IKKγ | Scaffold protein with coiled-coil domains | Regulatory subunit for canonical signaling |

Canonical NF-κB Pathway

Activation Mechanisms

The canonical NF-κB pathway is characterized by its rapid activation kinetics, typically occurring within minutes of cellular stimulation [10]. This pathway responds to a diverse array of stimuli including proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement, and other inflammatory mediators [8] [11]. The activation mechanism proceeds through a well-defined sequence of molecular events:

Receptor Proximal Signaling: Ligand binding to specific receptors (e.g., TNFR, TLR, TCR) initiates the recruitment of adapter proteins and signaling complexes. For instance, TCR engagement leads to the formation of the CBM complex (CARMA1, BCL10, MALT1), which recruits TRAF6 and TAK1, while TNFR signaling involves TRADD and RIP1 recruitment [8].

IKK Complex Activation: The multi-subunit IKK complex, composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO, becomes activated through phosphorylation events. TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1) has been identified as a key upstream kinase responsible for phosphorylating IKKβ at serine residues 177 and 181 within its activation loop [12] [13].

IκB Phosphorylation and Degradation: Activated IKK phosphorylates IκBα at two N-terminal serine residues (Ser32 and Ser36), targeting it for K48-linked polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [12] [13].

NF-κB Nuclear Translocation: Degradation of IκBα unmasks the nuclear localization sequences of NF-κB dimers (primarily p50-RelA and p50-c-Rel), enabling their translocation to the nucleus where they bind to specific κB enhancer elements and regulate target gene expression [10].

The canonical pathway is subject to tight negative feedback regulation, as NF-κB induces the transcription of IκBα, which subsequently re-accumulates in the nucleus, binds NF-κB, and exports it back to the cytoplasm to terminate the response [10].

Experimental Analysis of Canonical Pathway

Investigation of the canonical NF-κB pathway employs multiple experimental approaches:

- IKK Kinase Assays: Measurement of IKK activity through in vitro kinase assays using IκBα as substrate, often with immunoprecipitated IKK complex from stimulated cells [13].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA: Detection of NF-κB DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts using radiolabeled κB probes [7].

- Immunofluorescence Microscopy: Visualization of NF-κB nuclear translocation using antibodies specific for p65 or other subunits [10].

- Reporter Gene Assays: Monitoring NF-κB transcriptional activity using constructs with κB sites driving luciferase or other reporter genes [7].

- Western Blot Analysis: Assessment of IκBα degradation and phosphorylation, IKK phosphorylation, and processing of NF-κB precursors [13].

Computational models, including Petri nets and ordinary differential equation (ODE)-based approaches, have been developed to simulate the dynamic behavior of the canonical pathway and predict the effects of perturbations [14] [15].

Canonical NF-κB Activation Pathway

Non-canonical NF-κB Pathway

Activation Mechanisms

The non-canonical NF-κB pathway exhibits distinct characteristics compared to the canonical pathway, including slower activation kinetics (occurring over hours rather than minutes) and responsiveness to a more limited set of stimuli [10] [11]. Key activators include ligands for specific TNF receptor superfamily members such as CD40L, BAFF, RANKL, LTβ, and TWEAK [8] [11]. The activation mechanism proceeds through the following steps:

Receptor Engagement and TRAF Recruitment: Ligand binding to specific TNFR superfamily members leads to the recruitment of adapter proteins including TRAF2, TRAF3, and cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP1/2) [15].

NIK Stabilization: Under basal conditions, TRAF3 promotes constitutive degradation of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) through the action of cIAP1/2. Receptor activation induces degradation of TRAF3, resulting in the stabilization and accumulation of NIK [9] [11].

IKKα Activation: Accumulated NIK phosphorylates and activates IKKα homodimers, which do not require NEMO for their activation in this pathway [12].

p100 Phosphorylation and Processing: Activated IKKα phosphorylates the NF-κB2 precursor p100, leading to its polyubiquitination and partial degradation by the proteasome. This processing event generates mature p52 and releases the inhibitory C-terminal domain [9] [11].

Nuclear Translocation: The processed p52 forms a transcriptionally active complex with RelB, which translocates to the nucleus to regulate specific target genes involved in lymphoid organ development, B cell survival, and adaptive immunity [8] [11].

The non-canonical pathway features a negative feedback mechanism wherein IKKα phosphorylates NIK, targeting it for degradation and thus limiting the duration of pathway activation [15].

Experimental Analysis of Non-canonical Pathway

Specific methodologies for investigating the non-canonical pathway include:

- NIK Stabilization Assays: Immunoblot analysis to detect NIK accumulation following receptor engagement, often using inhibitors to block protein synthesis (cycloheximide) to measure protein half-life [11].

- p100 Processing Assays: Western blot analysis to monitor the conversion of p100 to p52 using antibodies that distinguish between the precursor and processed forms [9].

- Gene Knockout Models: Utilization of genetically modified mice lacking specific non-canonical pathway components (NIK, IKKα, RelB, p100) to elucidate pathway functions in vivo [12].

- In Silico Knockout Analyses: Computational approaches, such as Petri net models, to simulate the effects of protein knockouts and identify critical regulatory nodes [14] [15].

Petri net modeling of the non-canonical pathway has revealed a more diverse regulatory capacity compared to the canonical pathway and has helped quantify the relevance of individual biochemical processes, such as the relationship between NIK synthesis and p100 processing [14].

Non-canonical NF-κB Activation Pathway

Comparative Analysis of Activation Pathways

Structural and Functional Differences

The canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways demonstrate distinct characteristics in their activation mechanisms, kinetic profiles, and biological functions. Table 2 provides a systematic comparison of these two pathways based on current experimental evidence.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Canonical and Non-canonical NF-κB Pathways

| Parameter | Canonical Pathway | Non-canonical Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Key Stimuli | TNF-α, IL-1, LPS, TCR/CD28, TLR ligands | CD40L, BAFF, RANKL, LTβ, TWEAK |

| Primary Receptors | TNFR, IL-1R, TLR, TCR | Subset of TNFR superfamily (CD40, BAFF-R, RANK, LTβR) |

| Key Adaptor/Signaling Molecules | TRAF6, TAK1, CARMA1/BCL10/MALT1 (in lymphocytes) | TRAF2/TRAF3, cIAP1/2, NIK |

| IKK Complex Composition | IKKα, IKKβ, NEMO | IKKα homodimers |

| Central Regulatory Kinase | IKKβ | NIK and IKKα |

| Inhibitory Target | IκBα (phosphorylation/degradation) | p100 (phosphorylation/processing) |

| Primary NF-κB Dimers | p50-RelA, p50-c-Rel | p52-RelB |

| Activation Kinetics | Rapid (minutes) | Slow (hours) |

| Feedback Regulation | IκBα resynthesis | NIK degradation by IKKα |

| Primary Biological Functions | Innate immunity, inflammation, cell survival | Lymphoid organogenesis, B cell survival, adaptive immunity |

| Pathway Crosstalk | Regulates expression of p100 and RelB | NIK can enhance canonical IKK activation |

Pathway Crosstalk and Integration

Despite their distinct activation mechanisms, the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways do not function in complete isolation but exhibit significant crosstalk that enables integrated cellular responses [14] [15]. Computational modeling using Petri nets has revealed several key mechanisms of pathway interaction in CD40L-stimulated B cells:

NIK-Mediated Crosstalk: Accumulated NIK in the non-canonical pathway can contribute to the phosphorylation of IKKα and enhance activation of the canonical IKK complex under specific conditions [15].

p100 as a Shared Regulator: The precursor protein p100 can function as an IκB-like molecule for canonical dimers, particularly p50-RelA. Processing of p100 in the non-canonical pathway therefore liberates not only p52-RelB but also canonical NF-κB dimers that may be sequestered by p100 [15].

Transcriptional Interdependence: The canonical pathway regulates the expression of key non-canonical components, including p100 and RelB, creating a hierarchical relationship where canonical signaling can prime cells for non-canonical responses [8].

Dimer Interference: At the level of NF-κB subunit interaction, RelA can bind to RelB and prevent its DNA binding, demonstrating another layer of potential regulation between the two pathways [8].

In silico knockout analyses based on Petri net models have demonstrated that the activation of transcription factors p50-RelA and p52-RelB is affected by most knockouts of pathway components, confirming the interconnected nature of these signaling cascades [14].

Experimental Data and Research Methodologies

Key Experimental Findings

Quantitative analysis of NF-κB pathway dynamics has yielded important insights into their regulatory mechanisms:

Computational Modeling: Petri net models of CD40 receptor signaling demonstrated that the non-canonical NF-κB pathway exhibits more diverse regulatory capabilities than the canonical pathway [14]. In silico knockout analyses quantified the relevance of individual biochemical processes and successfully predicted interrelationships between NIK synthesis and p100 processing [14] [15].

Kinetic Profiling: The canonical pathway activates within minutes following stimulation, while non-canonical pathway activation occurs over several hours, reflecting their different biological roles in rapid response versus sustained signaling [10] [11].

Stoichiometric Analysis: Structural studies have revealed that IκBα masks the nuclear localization sequence of p65 but not that of p50, explaining how importin proteins can facilitate nuclear import of p50-p65 dimers even when complexed with IκBα [10].

Table 3: Quantitative Properties of NF-κB Pathway Components

| Parameter | Canonical Pathway | Non-canonical Pathway | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Time Course | 5-30 minutes | 2-8 hours | Live-cell imaging, western blot time course [10] [11] |

| NIK Stability (Half-life) | Not applicable | Basal: <30 minStimulated: >3 hours | Cycloheximide chase assays [11] |

| p100 Processing Efficiency | Minimal | Up to 40-60% of cellular p100 | Densitometric analysis of p100/p52 ratio [9] |

| Negative Feedback Time | 30-60 minutes (IκBα resynthesis) | 4-8 hours (NIK degradation) | Mathematical modeling, protein stability assays [10] [15] |

| Nuclear Translocation Efficiency | Up to 80% of cellular p65 | 20-40% of cellular RelB | Quantitative immunofluorescence, subcellular fractionation [10] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for NF-κB Pathway Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitors | IKK-16 (IKKβ inhibitor), BMS-345541 (IKK complex inhibitor), MLN120B (IKKβ inhibitor), ACHP (IKKα/β inhibitor) | Pathway-specific inhibition, therapeutic target validation | Selective blockade of canonical signaling |

| NIK Inhibitors (e.g., NIK SMI1), IKKα Allosteric Inhibitors | Non-canonical pathway dissection | Selective inhibition of non-canonical activation | |

| Antibodies for Detection | Anti-phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36), Anti-phospho-IKKα/β (Ser176/180) | Canonical pathway activation monitoring | Detection of key phosphorylation events |

| Anti-NIK, Anti-phospho-p100 (Ser866/870), Anti-p52 (non-canonical specific) | Non-canonical pathway activation assessment | Detection of NIK accumulation and p100 processing | |

| Anti-p65, Anti-p50, Anti-RelB, Anti-c-Rel | Subunit-specific analysis | Differentiation of NF-κB dimer composition | |

| Activity Assays | NF-κB Reporter Lentiviruses (κB-driven luciferase/GFP), EMSA Kits, NF-κB DNA Binding ELISA | Transcriptional activity measurement | Quantification of NF-κB functional output |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib, Lactacystin | Mechanism investigation | Blockade of IκBα/p100 degradation to confirm pathway dependence |

| Cytokines/Ligands | Recombinant TNF-α, IL-1β, CD40L, BAFF, RANKL | Pathway-specific stimulation | Selective activation of canonical vs. non-canonical pathways |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA/shRNA Libraries, CRISPR/Cas9 KO Cells, Transgenic Mouse Models | Functional genomics studies | Loss-of-function analysis of pathway components |

The comparative analysis of canonical and non-canonical NF-κB activation pathways reveals a sophisticated regulatory network that enables cells to mount appropriately tailored responses to diverse immunological cues. While each pathway possesses distinct structural components, activation mechanisms, kinetic properties, and biological functions, their operational integration through multiple crosstalk mechanisms allows for coordinated regulation of inflammatory and immune processes.

From a translational perspective, the distinct molecular features of these pathways offer opportunities for selective therapeutic intervention. The development of pathway-specific inhibitors, particularly those targeting IKKβ for canonical signaling or NIK for non-canonical signaling, holds promise for treating inflammatory diseases, autoimmune conditions, and cancers with greater precision and reduced off-target effects. However, the interconnected nature of these pathways necessitates careful consideration of potential compensatory mechanisms and network adaptations when designing therapeutic strategies.

Future research directions should focus on further elucidating the context-specific crosstalk mechanisms between these pathways, developing more sophisticated computational models that can predict system-level responses to perturbations, and advancing the characterization of tissue-specific and cell-type-specific differences in NF-κB pathway regulation. Such efforts will enhance our understanding of NF-κB as a critical inflammatory marker and facilitate the development of targeted therapies for conditions driven by dysregulated NF-κB activation.

The Janus kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway is a principal mechanism by which cytokines, interferons, and growth factors convey signals from the cell membrane to the nucleus, directly influencing gene transcription [16] [17]. Discovered more than a quarter-century ago, this pathway acts as a fulcrum for vital cellular processes including hematopoiesis, immune fitness, inflammation, and apoptosis [16]. The pathway comprises three key components: cell surface receptors, Janus kinases (JAKs), and STAT proteins [17]. More than 50 cytokines and growth factors, such as interferons (IFN) and interleukins (ILs), utilize this pathway [16] [18].

The mammalian STAT family consists of seven members: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6 [18] [19]. These proteins share a common domain structure that enables them to perform their dual roles: signal transduction in the cytoplasm and transcription activation in the nucleus [18] [20]. The canonical activation of STATs is triggered by the phosphorylation of a single tyrosine residue located near the carboxy terminus. This phosphorylation, typically mediated by JAKs, leads to STAT dimerization via reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions, revealing a nuclear localization signal. The STAT dimer then translocates to the nucleus, binds to specific DNA sequences (generally TTCN~3~GAA), and regulates the transcription of target genes [18].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of two key STAT family members, STAT1 and STAT3, which are often activated by common cytokines but frequently mediate opposing biological functions, particularly in the contexts of cancer and inflammation [18] [21]. We will objectively compare their roles, supported by experimental data, and provide detailed methodologies for key experiments in the field.

Comparative Analysis of STAT1 and STAT3

Structural Similarities and Activation Mechanisms

STAT1 and STAT3, like all STAT proteins, share conserved structural domains: an N-terminal domain, a coiled-coil domain, a DNA-binding domain, a linker region, an Src homology 2 (SH2) domain, and a C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) containing a conserved tyrosine phosphorylation site [18] [17]. Despite these structural similarities, they are activated by distinct but overlapping sets of cytokines and exhibit differences in their nuclear import mechanisms. For instance, STAT1 and STAT2 bind to importin α5 for nuclear entry, whereas STAT3 can bind to importin α3 and importin α6 [17].

Table 1: Key Activators and Primary Functions of STAT1 and STAT3

| Feature | STAT1 | STAT3 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Activators | IFN-γ, IFN-α/β [19] [21] | IL-6, IL-10, IL-23, IL-11, LIF, OSM [19] |

| Associated JAKs | JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 [16] [21] | JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 [16] |

| Dimer Form | Homodimers or heterodimers with STAT2 [19] | Homodimers [19] |

| Core Biological Functions | Anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic, tumor-suppressive, TH1 immunity [18] [19] [21] | Pro-proliferative, pro-survival, oncogenic, TH17 immunity [18] [19] |

| Role in Tumorigenesis | Tumor suppressor [21] | Oncogene [21] |

Opposing Roles in Cancer and Immunity

STAT1 and STAT3 are generally viewed as mediating opposite roles in cancer development and immune responses [18].

- STAT1 as a Tumor Suppressor and Immunostimulator: STAT1 is a central mediator of interferon signaling and is crucial for anti-viral and anti-tumor immunity [19] [21]. It functions as a tumor suppressor by inducing genes that lead to cell cycle arrest (e.g., p21WAF1/CIP1), promote apoptosis (e.g., caspases, IRF-1), and inhibit angiogenesis [21]. It is also pivotal for tumor immunosurveillance by driving the induction of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I molecules, which are essential for antigen presentation to T-lymphocytes [21].

- STAT3 as an Oncogene and Immune Suppressor: STAT3 was originally identified as "Acute Phase Response Factor" (APRF) and is a key mediator of physiologic responses to tissue injury [18] [19]. However, its constitutive activation is a common feature in a wide spectrum of human cancers, found in nearly 70% of solid and hematological tumors [21]. STAT3 promotes oncogenesis by regulating genes that enhance cell proliferation (e.g., Cyclin D1, c-MYC), survival (e.g., BCL-2, BCL-XL), angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF), and invasion [18] [19]. Furthermore, it suppresses anti-tumor immunity by inducing immunosuppressive proteins like PD-L1 and inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor cytokines such as IL-12 [19].

The Critical Balance: STAT1/STAT3 Ratio

Experimental and clinical evidence suggests that the relative expression and activation levels of STAT1 and STAT3—their ratio—is a critical determinant of cellular outcomes, particularly in cancer.

A study on colorectal cancer (CRC) patient samples found that the concomitant absence of nuclear STAT1 and STAT3 was associated with a significantly reduced median survival of at least 33 months [22]. Furthermore, patients with high nuclear STAT1 and low nuclear STAT3 activity had better overall survival compared to those with low STAT1 and low STAT3 activity [22].

To investigate this mechanistically, STAT3 was knocked down in four different CRC cell lines, which led to two distinct phenotypes [22]:

- In HCT116 and SW620 cells, STAT3 knockdown resulted in reduced STAT1 expression and accelerated tumor growth in mouse xenografts.

- In HT-29 and LS174T cells, STAT3 knockdown led to elevated STAT1 expression and reduced tumor growth.

This demonstrates that a low STAT1/high STAT3 expression ratio favors faster tumor growth, whereas a high STAT1/low STAT3 ratio correlates with slower tumor growth and better patient prognosis [22].

Table 2: Comparative Gene Regulation by STAT1 and STAT3 in Cancer

| Cellular Process | STAT1 Target Genes (Effect) | STAT3 Target Genes (Effect) |

|---|---|---|

| Proliferation & Cell Cycle | p21WAF1/CIP1 (Induces), c-MYC (Represses) [21] | Cyclin D1 (Induces), c-MYC (Induces) [18] [19] |

| Apoptosis & Survival | Caspases, IRF-1 (Pro-apoptotic) [21] | BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL1 (Anti-apoptotic) [19] |

| Angiogenesis | Inhibits VEGF response [21] | VEGF, HIF1A (Induces) [19] |

| Imm Modulation | MHC Class I, IL-12 (Induces) [19] [21] | PD-L1, IL-10, IL-6 (Induces); IL-12 (Represses) [18] [19] |

Experimental Protocols for STAT Analysis

To generate robust, reproducible data on STAT signaling, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key techniques used in the cited studies.

Protocol 1: Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis of STAT Expression and Localization in Patient Tissues

This protocol is used to correlate STAT protein levels and nuclear localization (an indicator of activation) with clinical outcomes, as performed on colorectal cancer tissue microarrays [22].

- Tissue Preparation: Formalin-fix and paraffin-embed (FFPE) patient tissue biopsies. Section into 4-5 µm thick slices and mount on slides.

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Deparaffinize slides in xylene and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%) to water.

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) by incubating slides in a citrate-based buffer (pH 6.0) or EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) using a pressure cooker or microwave.

- Blocking: Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2. Block non-specific binding with 2.5% normal horse or goat serum.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate sections overnight at 4°C with validated, specific primary antibodies.

- Anti-STAT1 and Anti-STAT3: To assess total protein expression.

- Anti-pY-STAT1 and Anti-pY-STAT3: To assess activated, tyrosine-phosphorylated protein.

- Detection: Use an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) system or a polymer-based detection kit with a chromogenic substrate like 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB).

- Counterstaining and Analysis: Counterstain with hematoxylin, dehydrate, and mount. Score staining intensity (e.g., 0, 1+, 2+, 3+) and percentage of positive cells separately for the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments by a pathologist blinded to the clinical data.

Protocol 2: STAT Functional Analysis using Knockdown and Xenograft Models

This method is used to determine the functional consequences of altering STAT levels on tumor growth, as demonstrated in CRC cell lines [22].

- Cell Line Selection: Choose relevant cancer cell lines with known genetic backgrounds (e.g., HCT116, SW620, HT-29, LS174T for CRC).

- STAT3 Knockdown: Generate stable STAT3-knockdown cell lines using lentiviral transduction with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting STAT3. Use a non-targeting shRNA as a negative control.

- Validation: Confirm knockdown efficiency at the mRNA level by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and at the protein level by western blot.

- Western Blot Analysis: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer. Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to a PVDF membrane, and probe with antibodies against STAT3, STAT1, and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH or β-Actin). Observe the reciprocal changes in STAT1 expression post-STAT3 knockdown.

- Xenograft Tumor Growth: Subcutaneously inject 1-5 x 106 control and STAT3-knockdown cells into the flanks of immunocompromised mice (e.g., SCID mice).

- Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions 2-3 times per week with calipers. Calculate tumor volume using the formula: Volume = (Length x Width2) / 2.

- Endpoint Analysis: Euthanize mice at a predetermined endpoint (e.g., when tumors in control group reach ~1500 mm³). Excise and weigh tumors for final comparison.

- IHC of Xenografts: Analyze the harvested xenograft tumors via IHC (as in Protocol 1) to confirm that the STAT1/STAT3 expression profile is maintained in vivo.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core JAK-STAT signaling module and the central antagonistic relationship between STAT1 and STAT3.

Diagram 1: Core JAK-STAT signaling pathway and the functional balance between STAT1 and STAT3. The pathway is activated by cytokines, leading to STAT phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation to regulate transcription. The cellular outcome is determined by the balance between the opposing functions of STAT1 and STAT3.

Diagram 2: Regulatory mechanisms and pathologies of the JAK-STAT pathway. Signaling is tightly controlled by negative regulators like SOCS, PTPs, and PIAS. Dysregulation, such as gain-of-function mutations in STAT1 or STAT3, leads to distinct autoimmune and immunodeficiency syndromes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research into STAT biology relies on a suite of well-validated reagents and tools. The table below lists essential materials for key experimental approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for STAT Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines & Activators | Recombinant IFN-γ, IL-6 | To specifically activate STAT1 (IFN-γ) or STAT3 (IL-6) pathways in cell-based assays [22] [21]. |

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-STAT1, Anti-STAT3, Anti-pY-STAT1, Anti-pY-STAT3 | For detecting total and activated protein levels in techniques like Western blot, immunofluorescence, and IHC [22]. |

| Cell Lines | HCT116, HT-29, SW620, LS174T (CRC models) | Well-characterized models with known mutational backgrounds for in vitro and in vivo (xenograft) studies of STAT function [22]. |

| Knockdown Tools | Lentiviral shRNA constructs targeting STAT3 | For generating stable gene knockdown cell lines to study the functional consequences of protein loss-of-function [22]. |

| JAK Inhibitors | Tofacitinib, Ruxolitinib | Small molecule inhibitors used to broadly block JAK-STAT signaling; used both therapeutically and as a research tool to probe pathway necessity [23]. |

| Cytokine Blockers | Tocilizumab (anti-IL-6R) | Therapeutic monoclonal antibody used to block specific cytokine signals (e.g., IL-6) that activate STAT3; used in research and clinics [23]. |

| Nicardipine Hydrochloride | Nicardipine Hydrochloride | Research-grade Nicardipine Hydrochloride, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker for cardiovascular studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Nifekalant | Nifekalant, CAS:130636-43-0, MF:C19H27N5O5, MW:405.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

STAT1 and STAT3 are pivotal transcription factors downstream of the JAK-STAT pathway that execute profoundly different, and often opposing, cellular programs. While STAT1 generally drives anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic, and immunostimulatory responses, STAT3 promotes pro-survival, proliferative, and immunosuppressive outcomes. The critical finding from comparative studies is that the functional balance between STAT1 and STAT3, often quantified as their expression or activation ratio, is a key determinant in physiological and pathological processes like cancer and inflammation [22] [21].

This balance presents a compelling therapeutic paradigm. Rather than simply inhibiting the entire JAK-STAT pathway, future strategies could aim to therapeutically "rebalance" the STAT1/STAT3 ratio in favor of anti-tumor or anti-inflammatory responses. The use of JAK inhibitors in STAT gain-of-function diseases exemplifies the successful targeting of this pathway [23]. A deep understanding of the differential roles and intricate cross-regulation of STAT1 and STAT3 is therefore fundamental for developing novel, targeted therapies in oncology and immunology.

The Interferon Regulatory Factor (IRF) family represents a crucial class of transcription factors that serve as master regulators of the immune system, functioning at the critical interface between physiological defense mechanisms and pathological inflammatory processes. Comprising nine members in mammals (IRF1 through IRF9), these factors share a conserved evolutionary architecture while exhibiting remarkable functional diversity in regulating interferon responses, immune cell development, and inflammatory pathways [24]. Initially identified as regulators of type I interferon (IFN-I) and IFN-responsive genes, IRFs have since been recognized as pivotal players in a broad spectrum of biological processes, from antiviral defense to oncogenesis [24] [25]. Their dual nature as both protective factors and potential drivers of pathology makes them compelling subjects for comparative analysis in transcription factor research, particularly as biomarkers for inflammatory conditions and targets for therapeutic intervention [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of IRF family members, their regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches for their study, offering researchers a framework for understanding their complex roles in health and disease.

Comparative Analysis of IRF Family Members

Structural Organization and Functional Domains

All IRF family members share a conserved multi-domain structure that facilitates their function as transcription factors while allowing for functional specialization:

DNA-Binding Domain (DBD): A highly conserved N-terminal domain comprising approximately 120 amino acids that form a helix-turn-helix motif, enabling recognition of specific DNA sequence elements (A/GNGAAANNGAAACT) known as interferon-stimulated response elements (ISREs) in promoter regions [24] [25]. This domain contains five tryptophan repeats and is responsible for target gene specificity.

C-Terminal Regulatory Domains: The C-terminal regions contain either an IFN association domain 1 (IAD1 in IRF3, IRF4, IRF5, IRF6, IRF7, IRF8, and IRF9) or IAD2 (in IRF1 and IRF2) with low sequence homology, serving as association domains for interactions with other IRF members, transcription factors, and cofactors [24]. These domains confer functional specificity and regulate activation states.

Variable Regulatory Regions: Many IRF proteins contain regulatory regions between the DBD and IAD that include multiple phosphorylation sites and other post-translational modification motifs that control activity, stability, and subcellular localization [24].

Table 1: Structural and Functional Characteristics of IRF Family Members

| IRF Member | Gene Location | Protein Size (aa) | Key Domains | Primary Cellular Expression | Response to IFN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRF1 | 5q31.1 | 325 | DBD, IAD2 | Ubiquitous, low basal | Induced by IFN, TNF, IL-1 [24] |

| IRF2 | 4q35.1 | 349 (isoform 1) | DBD, IAD2 | Multiple cell types | Induced by viruses and IFN [24] |

| IRF3 | 19q13.33 | ~427 (human) | DBD, IAD1 | Ubiquitous | Virus-induced [24] |

| IRF4 | 6p25.3 | 451 | DBD, IAD1 | Lymphoid cells | Not regulated by IFNs [24] |

| IRF5 | 7q32.1 | 504 | DBD, IAD1 | Myeloid cells, B cells | Induced by viral infection [24] |

| IRF6 | 1q32.2 | 467 | DBD, IAD1 | Epithelial cells, keratinocytes | Developmental focus [24] |

| IRF7 | 11p15.5 | 503 (IRF7A) | DBD, IAD1 | Spleen, thymus, PBLs, pDCs | Virus-induced, IFN-amplified [25] |

| IRF8 | 16q24.1 | 426 | DBD, IAD1 | Myeloid cells, dendritic cells | Regulated by IFN-γ [24] |

| IRF9 | 14q11.2 | 393 | DBD, IAD1 | Ubiquitous | Upregulated by IFN-γ [24] |

The structural organization of IRFs facilitates their function as transcriptional regulators while allowing for specialized roles in different immune contexts. The conserved DBD ensures recognition of similar DNA sequences, while the variable C-terminal regions and regulatory domains enable functional diversification and context-specific regulation.

Functional Specialization and Target Gene Specificity

IRF family members exhibit both redundant and specialized functions in immune regulation, with distinct roles in antiviral defense, immune cell development, and inflammatory responses:

Antiviral Defense Specialization: IRF3 and IRF7 serve as master regulators of the immediate-early and late phases of IFN-I production, respectively, with IRF7 playing a particularly crucial role in the amplification loop that generates robust IFN-α responses [25]. IRF1 contributes to antiviral responses through regulation of IFN-γ inducible genes, while IRF9 forms part of the ISGF3 complex that mediates signaling downstream of IFN-I receptors [24].

Immune Cell Development: IRF4 and IRF8 play critical roles in the development and differentiation of B cells, myeloid cells, and dendritic cells, while IRF1 and IRF2 are required for NK cell development [27]. IRF6 exhibits a unique developmental focus, with essential functions in epidermal and orofacial embryonic development rather than classical immune roles [24] [27].

Inflammatory Regulation: IRF5 has emerged as a key regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages, contributing to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, while IRF4 often exhibits anti-inflammatory properties in specific contexts [24]. IRF1 plays a role in pro-inflammatory responses in microglia in neurodegenerative diseases [26].

Table 2: Functional Specialization and Disease Associations of IRF Family Members

| IRF Member | Primary Immune Functions | Key Signaling Pathways | Disease Associations | Dual Roles in Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRF1 | NK cell development, antiviral response, pro-inflammatory responses | IFN-γ signaling, DNA damage response | Infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, cancer | Tumor suppressor vs. promoter depending on context [24] [26] |

| IRF2 | Antagonizes IRF1, immune regulation | Competitive binding with IRF1 | Cancer, viral persistence | Mainly antagonistic to IRF1 [24] |

| IRF3 | Early-phase IFN-I production, antiviral defense | RIG-I/MDA5, TLR3, TLR4 (TRIF-dependent) | Severe viral infections, neuroinflammation | Protective antiviral vs. neuroinflammatory driver [24] [26] |

| IRF4 | B-cell differentiation, Th cell polarization, anti-inflammatory effects | TLR (MyD88-dependent), BCR signaling | Lymphoma, autoimmune disease, inflammation | Oncogenic in lymphoma, anti-inflammatory in specific contexts [24] |

| IRF5 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine production, M1 macrophage polarization | TLR (MyD88-dependent) | SLE, RA, inflammatory diseases | Pro-inflammatory driver [24] |

| IRF6 | Epithelial development, keratinocyte differentiation, TLR regulation | TLR2, TLR4, NF-κB | Van der Woude syndrome, popliteal pterygium syndrome, endotoxic shock | Developmental defects, protective in endotoxic shock [24] [27] |

| IRF7 | Late-phase IFN-I amplification, IFN-α production, antiviral defense | TLR7/8/9 (MyD88-dependent), RIG-I/MDA5 | Severe viral infection, SLE, COVID-19 severity | Master antiviral regulator vs. driver of autoimmunity [25] |

| IRF8 | Myeloid and dendritic cell development, IL-12 production | IFN-γ signaling, GM-CSF signaling | Immunodeficiency, myeloid malignancies | Tumor suppressor in myeloid cancers [24] |

| IRF9 | ISGF3 complex formation, IFN signaling mediation | JAK-STAT signaling | Viral susceptibility, interferonopathies | Essential for IFN-I signaling [24] |

The functional specialization of IRF family members enables precise regulation of immune responses while creating vulnerabilities when specific members are dysregulated. Their dual roles in different disease contexts highlight the importance of context-specific analysis when evaluating their potential as therapeutic targets.

Experimental Analysis of IRF Function

Methodologies for Investigating IRF Regulation and Function

Research into IRF family functions employs a diverse array of experimental approaches designed to elucidate their complex roles in immune regulation:

Genetic Manipulation Models: Conditional knockout mice, such as the LysM-Cre;Irf6fl/fl model used to study myeloid-specific IRF6 functions, enable cell-type-specific analysis of IRF functions [27]. Global knockout models (e.g., Irf7-/- mice) have revealed essential roles in IFN-I amplification, with IRF7-deficient plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) showing almost complete loss of IFN-α production capacity [25].

Stimulus-Response Assays: Treatment with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as LPS (TLR4 agonist), PolyIC (TLR3/RIG-I agonist), or CpG DNA (TLR9 agonist) in wild-type versus knockout cells reveals IRF-specific contributions to downstream responses [28]. For example, IRF3/5/7 triple knockout cells show no IFN-β production upon PolyIC stimulation, while IRF3/7 double knockout cells produce minimal IFN-β [28].

Signal Transduction Analysis: Western blotting for phosphorylation events (e.g., phospho-IκBα, phospho-IRF7) and nuclear translocation assays provide insights into activation mechanisms [27]. For instance, IRF6-deficient macrophages show increased phosphorylated IκBα levels following LPS stimulation, suggesting enhanced NF-κB activation [27].

Gene Expression Profiling: Quantitative PCR and RNA sequencing of IRF-regulated genes (IFN-α, IFN-β, ISGs, pro-inflammatory cytokines) in stimulated wild-type versus knockout cells reveal transcriptional networks [27] [28]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays further identify direct transcriptional targets.

Protein Interaction Studies: Co-immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid systems identify interacting partners, such as the interaction between IRF4 and PU.1 or the formation of IRF3-IRF7 heterodimers [24] [25].

Experimental Workflow for IRF Characterization

Quantitative Analysis of IRF-Mediated Responses

The regulatory logic of IRF-mediated responses can be quantitatively analyzed using enhancer state models that account for combinatorial binding and synergistic interactions:

Combinatorial State Ensemble Modeling: Mathematical modeling of IFN-β enhancer regulation reveals multiple synergy modes between transcription factors. A three-site model incorporating NF-κB, proximal IRE1, and distal IRE2 binding sites accurately predicts stimulus-specific dependence patterns, with different synergy modes accessed in response to different immune threats [28].

Stimulus-Specific Activation Patterns: Viral stimuli (PolyIC) induce maximal IRF activation and can drive IFN-β expression through IRF synergy alone, while bacterial stimuli (LPS) induce maximal NF-κB with low IRF activation and require NF-κB for IFN-β expression [28]. This stimulus-specific regulation enables precise immune responses tailored to specific pathogens.

Kinetic Analysis of Signaling Pathways: Time-course studies reveal sequential activation of IRF members, with initial IRF3 activation followed by IRF7-mediated amplification. Phosphorylation events typically occur within minutes to hours post-stimulation, with nuclear translocation and gene expression changes following specific temporal patterns [25].

Table 3: Experimental Data from Key IRF Studies

| Experimental Context | Key Findings | Methodology | Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRF6 in endotoxic shock [27] | IRF6 deficiency increases susceptibility to LPS-induced lethality | Conditional knockout (LysM-Cre), LPS challenge (15 mg/kg), cytokine measurement | 100% mortality in Irf6 cKO vs. ~40% in WT; 2-3 fold increase in KC and IL-6 in macrophages |

| IRF7 in IFN-I amplification [25] | IRF7 essential for late-phase IFN-I production | IRF7-/- mice, viral infection, IFN-α measurement | >90% reduction in IFN-α in pDCs; complete loss of IFN-α subtypes in some contexts |

| IFN-β enhancer logic [28] | Stimulus-specific TF requirements for IFN-β expression | TF knockout models, stimulus response, mathematical modeling | PolyIC: NF-κB-independent; LPS: NF-κB-dependent; IRF3/5/7ko: complete ablation |

| IRF1 in neuroinflammation [26] | IRF1 drives pro-inflammatory microglial state | Microglial cultures, transcriptional profiling, IRF1 manipulation | Significant upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (2-5 fold) in AD models |

Quantitative analysis of IRF-mediated responses reveals complex regulatory logic that enables precise control of immune outcomes. The stimulus-specific and cell-type-specific nature of these responses highlights the importance of context in interpreting experimental results.

IRF Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Key Signaling Pathways in IRF Activation

IRF family members are activated through distinct signaling pathways that translate pathogen recognition into specific transcriptional responses:

RIG-I-like Receptor (RLR) Pathway: Cytosolic viral RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 signal through the mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) to activate TBK1 and IKKε kinases, which phosphorylate IRF3 and IRF7, leading to their dimerization and nuclear translocation [25] [29].

Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Pathways: Endosomal TLRs (TLR3, TLR7/8, TLR9) activate distinct pathways; TLR3 signals through TRIF to activate TBK1/IKKε and IRF3/7, while TLR7/8/9 signal through MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK1-TRAF6 to directly activate IRF7 [25]. TLR4 signals through both MyD88 (primarily NF-κB) and TRIF (IRF3/7) pathways [29].

cGAS-STING Pathway: Cytosolic DNA sensors like cGAS generate cyclic GAMP (cGAMP) that activates STING, leading to TBK1-mediated phosphorylation of IRF3 and induction of IFN-I responses [26] [29].

JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway: IFNR engagement activates JAK1 and TYK2, leading to phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2, which form the ISGF3 complex with IRF9. This complex translocates to the nucleus and binds ISRE elements to induce interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [29].

IRF Activation Signaling Cascade

Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling IRF Activity

IRF family members are subject to multiple layers of regulation that ensure appropriate activation dynamics and prevent excessive inflammation:

Post-Translational Modifications: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, and SUMOylation precisely control IRF activation, stability, and subcellular localization [24]. For example, phosphorylation of IRF7 at Ser477 and Ser479 is essential for its nuclear translocation and activation [25].

Negative Feedback Loops: Several IRF-induced proteins, including SOCS1, USP18, and TRIM proteins, provide negative feedback to limit IRF signaling duration and intensity, preventing excessive inflammation [30].

Competitive Interactions: Some IRF members act as antagonists; IRF2 competes with IRF1 for the same promoter elements, while IRF4 can antagonize other IRFs in certain contexts [24].

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns: Restricted expression of certain IRFs (e.g., IRF4 in lymphoid cells, IRF5 in myeloid cells) creates cell-type-specific regulatory networks [24] [27].

The complex regulatory networks controlling IRF activity ensure balanced immune responses that effectively combat pathogens while minimizing collateral damage to host tissues. Dysregulation of these control mechanisms contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for IRF Family Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Models | Irf6fl/fl mice [27], LysM-Cre [27], Irf7-/- mice [25] | Cell-type-specific function analysis, whole-organism physiology | Conditional vs. global knockout strategies; background strain effects |

| Stimuli & Agonists | LPS (TLR4) [27], PolyIC (TLR3/RIG-I) [28], CpG DNA (TLR9) [28] | Pathway-specific activation, stimulus-response profiling | Dose optimization, kinetics, endotoxin contamination controls |

| Antibodies | Anti-IRF6 [27], Phospho-IκBα [27], CD11b [27], Ly-6G [27] | Protein detection, phosphorylation status, cell isolation | Validation in knockout systems, species cross-reactivity |

| Cell Isolation | Bone marrow-derived macrophages [27], neutrophils [27], dendritic cells [27] | Primary cell studies, cell-type-specific mechanisms | Differentiation protocols, purity assessment (flow cytometry) |

| Assay Systems | EZ-TAXIScan [27], Cytokine ELISA/Luminex [27], qPCR [27] | Functional assays, cytokine measurement, gene expression | Multiplexing capabilities, dynamic range, normalization controls |

| Pathway Modulators | EPZ-6438 (IRF1 modulator) [26], H-151 (cGAS-STING inhibitor) [26] | Mechanistic studies, therapeutic potential exploration | Specificity validation, off-target effects assessment |

This toolkit provides the essential resources for investigating IRF family functions across experimental contexts. Appropriate selection and validation of these reagents is crucial for generating reliable, reproducible data in IRF research.

The IRF family represents a class of transcription factors with master regulatory roles in interferon responses and immune regulation, functioning as critical nodes in the interface between innate immunity and inflammatory pathology. Their structural conservation coupled with functional specialization enables precise control of immune responses while creating vulnerabilities when dysregulated. The dual nature of many IRF members—acting as both protective factors and potential drivers of pathology—highlights the importance of context-specific understanding for therapeutic targeting. Current research continues to elucidate the complex regulatory networks controlling IRF activity and the potential for targeting specific IRF members in autoimmune diseases, cancer, and chronic inflammatory conditions. As our understanding of IRF biology advances, these transcription factors continue to offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in a wide range of inflammatory diseases.

In the realm of innate immunity and inflammatory responses, the transcriptome of immune cells undergoes drastic changes, a process tightly regulated by signal-regulated transcription factors (SRTFs) [31] [32]. Among these, three families stand out for their pivotal roles: Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB), Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STATs), and Interferon Regulatory Factors (IRFs). These factors do not operate in isolation; they form intricate, collaborative networks that integrate environmental cues to tailor inflammatory gene expression programs [31] [32]. This comparative analysis dissects the mechanisms of cross-talk between NF-κB, STATs, and IRFs, examining their unique and shared roles as inflammatory markers. Understanding these interactions is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to modulate immune responses in diseases ranging from chronic inflammation to cancer and COVID-19 [33] [7].

Structural Foundations and Activation Mechanisms

The distinct structures of NF-κB, STATs, and IRFs underpin their specific functions and their potential for molecular cross-talk.

NF-κB Family

The mammalian NF-κB transcription factor family comprises five members: NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), p65 (RELA), RELB, and c-REL [7]. The most common dimer, the p65/p50 heterodimer, is sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitors of κB (IκB) proteins. Activation via the I-kappaB kinase (IKK) complex—composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ/NEMO—triggers IκB phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation, freeing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus [32] [7]. The Rel homology domain (RHD) facilitates DNA binding and dimerization, while RELA, RELB, and c-REL possess C-terminal transactivation domains (TADs) essential for driving transcription [7].

STAT Family

The seven STAT family members (STATs 1-4, 5a, 5b, and 6) are primarily activated by Janus kinase (JAK)-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation in response to cytokines [32] [2]. This phosphorylation induces STAT dimerization, stabilized by reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions, and exposes a nuclear localization signal. STAT dimers recognize gamma-interferon-activated sequences (GAS, TTCN3-4GAA) [2]. A key complex, ISGF3, formed by phosphorylated STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9, binds to interferon-stimulated response elements (ISREs) to activate a broad antiviral transcriptome [32] [2].

IRF Family

The nine IRF family members (IRF1-9) share a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain with a characteristic tryptophan cluster that recognizes IRF-element (IRF-E) sequences (5′-GAAA-3′), a core part of the ISRE [2]. Their C-terminal IRF association domain (IAD) mediates homo- and heterodimerization. Key IRFs like IRF3 and IRF7 are activated through phosphorylation by IKK-related kinases (TBK1 and IKKε), leading to dimerization and nuclear translocation, where they are master regulators of type I interferon genes [32] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Structural and Activation Features of NF-κB, STAT, and IRF Families

| Feature | NF-κB | STATs | IRFs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Members | p65, p50, RELB, c-REL | STAT1, STAT2, STAT3 | IRF1, IRF3, IRF5, IRF7, IRF9 |

| DNA-Binding Domain | Rel Homology Domain (RHD) | - | Helix-turn-helix (tryptophan cluster) |

| Dimerization Domain | RHD | SH2 domain (pY-mediated) | IRF Association Domain (IAD) |

| Primary Activation Trigger | PRRs, TNF receptor, IL-1R | Cytokine receptors (JAK-STAT) | PRRs (TLRs, cytosolic sensors) |

| Key Activation Kinase | IKKα/IKKβ (canonical) | JAKs | TBK1/IKKε (IRF3/7), IKKβ (IRF5) |

| Cytoplasmic Retention | IκB proteins | Latent, unphosphorylated | Latent, inactive conformations |

| Consensus DNA Sequence | 5′-GGGRNWYYCC-3′ | GAS: TTCN3-4GAA | ISRE/IREF: 5′-PuPuAAANNGAAAPyPy-3′ |

Figure 1: Simplified Overview of NF-κB, STAT, and IRF Activation and Nuclear Cross-Talk. External stimuli (e.g., LPS, TNF, IFNs, viral RNA) activate distinct cytoplasmic signaling pathways, leading to the phosphorylation, activation, and nuclear translocation of these transcription factors. In the nucleus, they collaborate to drive the expression of inflammatory, antiviral, and interferon genes [31] [32] [7].

Modes of Transcriptional Cross-Talk

The interplay between NF-κB, STATs, and IRFs is not merely parallel but involves direct and functional integration, creating a sophisticated regulatory network.

Direct Complex Formation and Synergistic Gene Activation

A prime example of direct collaboration is the formation of the ISGF3 complex, which consists of phosphorylated STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9. This complex binds to ISREs to potently induce interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), demonstrating how STAT and IRF families physically interact for a common transcriptional goal [32] [2]. Furthermore, STAT3 can interact directly with the NF-κB subunit p65 at the promoters of specific genes, such as fascin. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays have revealed that IL-6 and TNF-α stimulation induces transcriptional synergy between STAT3 and NF-κB, amplifying the inflammatory response [33].

Mutual Regulation of Expression and Activity

Transcription factors within this network often regulate each other's expression or activation. For instance, NF-κB is a key regulator of TNF-α expression, while STAT1 and IRF1 are induced by IFN-γ signaling, creating a cytokine-mediated feedback loop [33]. This mutual regulation can create oscillatory dynamics, as seen with NF-κB, which induces its own inhibitor IκBα, leading to pulsatile activation [34]. In severe COVID-19, a delayed type I IFN response (governed by IRFs) compromises early antiviral defense and intensifies downstream NF-κB-driven inflammation, illustrating how temporal dysregulation in one arm disrupts the entire network [33].

Chromatin-Level Cooperation

The genome's landscape, pre-configured by pioneer and lineage-determining transcription factors (LDTFs), profoundly influences SRTF activity. For example, in macrophages, IRF1 functions as a pioneer factor that regulates chromatin accessibility at interferon-stimulated gene loci. This priming of the chromatin state determines whether TLR4 or TLR8 stimulation will lead to a robust ISG response, showcasing how an IRF sets the stage for subsequent inflammatory gene expression [35]. The collaborative interplay between LDTFs and SRTFs like STATs, IRFs, and NF-κB ensures a cell-type and stimulus-specific transcriptional output [31] [32].

Table 2: Documented Functional Interactions Between NF-κB, STATs, and IRFs

| Interaction Type | Specific Example | Functional Outcome | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Complex Formation | STAT1-STAT2-IRF9 (ISGF3) | Activation of antiviral ISGs | Biochemical complex purification, ISRE-luciferase reporter assays [32] [2] |

| Promoter-Level Cooperation | STAT3 and p65 (RelA) at fascin promoter | Enhanced cell migration and invasion | ChIP assays showing co-occupancy after IL-6/TNF-α stimulation [33] |

| Expression Regulation | NF-κB drives TNFα; TNFα activates NF-κB | Positive feedback loop amplifying inflammation | Knockdown/knockout models, cytokine measurements (ELISA) [33] [34] |

| Synergistic Antagonism | IRF5 and NF-κB p65 | Cooperative pro-inflammatory gene induction | Gene expression profiling in IRF5-deficient macrophages [32] |

| Chromatin Remodeling | IRF1 pioneer activity | Sets chromatin accessibility for ISG response | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq in human monocytes/macrophages [35] |

Experimental Analysis of Cross-Talk: Methodologies and Reagents

Deciphering these complex networks requires a multi-faceted experimental approach, combining molecular, biochemical, and genomic techniques.

Key Experimental Protocols

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): This is a cornerstone method for mapping the physical interactions between transcription factors and DNA. The protocol involves cross-linking proteins to DNA in living cells, lysing and shearing chromatin, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complex with a specific antibody (e.g., anti-p65, anti-STAT3, anti-IRF1), and then quantifying the associated DNA sequences by PCR or sequencing (ChIP-seq) [33]. ChIP-seq allows for genome-wide identification of binding sites and can reveal co-occupancy of different factors on the same genomic region.

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): Used to study protein-DNA interactions in vitro. Nuclear extracts are incubated with a labeled DNA probe containing a specific binding site (e.g., a GAS or κB site). If a transcription factor binds the probe, the complex migrates more slowly in a gel, causing a "shift." Supershifts with specific antibodies can confirm the identity of the binding protein [7].

- Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay: This functional assay measures transcriptional activity. A promoter or enhancer region containing a putative binding site (e.g., an ISRE or κB site) is cloned upstream of a luciferase gene. This construct is transfected into cells, which are then stimulated. The resulting luminescence, measured with a luminometer, directly reports the level of transcriptional activation driven by that element.

- Cytokine/Chemokine Profiling: The functional output of transcription factor cross-talk is often the secretion of inflammatory mediators. Techniques like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) or multiplex bead-based arrays (e.g., Luminex) are used to quantitatively measure concentrations of proteins like TNF-α, IL-6, and IFNs in cell culture supernatants or patient serum [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying NF-κB, STAT, and IRF Pathways

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IFNs) | Specific pathway activation. | Stimulating cells to activate NF-κB (TNFα), STAT (IFNs), or IRF (IFNs) pathways [34]. |

| TLR Agonists (e.g., LPS) | Activate PRR signaling upstream of NF-κB and IRFs. | Inducing a broad inflammatory response in macrophages [34] [35]. |

| Pathway-Specific Inhibitors | Chemically inhibit key kinases. | BAY 11-7082 (IKK inhibitor); JAK inhibitors (Ruxolitinib); TBK1/IKKε inhibitors (MRT67307) [7]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect activated (phosphorylated) forms of TFs. | Western blot or Flow Cytometry to monitor p65 (Ser536), STAT1 (Tyr701), STAT3 (Tyr705), IRF3 (Ser386) [34]. |

| siRNA/shRNA & CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Knockdown or knockout specific transcription factors. | Validating the specific role of IRF5 vs. IRF7 in gene regulation [32] [35]. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Block the activity of specific extracellular ligands. | Isolating the contribution of TNFα in a complex cytokine mixture (e.g., macrophage supernatant) [34]. |

| Rabdosin B | Rabdosin B|CAS 84304-92-7|Supplier | Rabdosin B is an ent-kaurene diterpenoid with anticancer effects, inducing DNA damage. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Rabeprazole Sodium | Rabeprazole Sodium, CAS:117976-90-6, MF:C18H20N3NaO3S, MW:381.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Figure 2: A Generalized Experimental Workflow for Investigating Transcription Factor (TF) Cross-Talk. Research typically begins with selecting an appropriate cellular model, followed by genetic or chemical perturbations and specific stimulation. Analysis proceeds through multiple, often complementary, readouts—biochemical, genomic, and functional—the results of which are integrated to build a coherent model of the interactions [33] [34] [35].

Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Implications

Dysregulation of the NF-κB/STAT/IRF network is a hallmark of numerous diseases, making its components attractive therapeutic targets.

Role in Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases

In COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 manipulates this transcriptional network to evade immunity. The virus promotes NRF2 degradation, dampening the oxidative stress response, and modulates NF-κB activity through viral proteins like NSP6 and ORF7a, contributing to the hyperinflammation and cytokine storm seen in severe cases [33]. The delayed IFN-I response (involving IRF3/IRF7) is a critical factor that allows unchecked viral replication and exacerbates NF-κB-driven pathology [33]. In the liver, the differential activation of NF-κB by IL-1β versus TNFα influences life/death decisions in hepatocytes during inflammatory stress, with TNFα promoting FasL-induced apoptosis while IL-1β favors survival through distinct NF-κB target gene expression [34].

Role in Cancer and Atherosclerosis

Within the tumor microenvironment, persistent NF-κB and STAT3 activation sustains chronic inflammation that promotes cancer cell proliferation and survival [33] [7]. In atherosclerosis, the interplay between KLF4, STATs, IRFs, and NF-κB drives vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) phenotypic switching and macrophage polarization, key processes in plaque formation and instability [36]. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, induced by IFNγ and TLR ligands via STAT1 and IRF5, contribute to tissue damage, whereas STAT6-driven M2 macrophages promote resolution [36].

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Several strategies to therapeutically modulate this network are under development:

- IKK Inhibitors: Target the canonical NF-κB pathway but require careful management of side effects [7].

- JAK Inhibitors: Already in clinical use for autoimmune diseases, these drugs indirectly impact STAT activity [7].

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Block the degradation of IκB, thereby inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation. Bortezomib is an example used in multiple myeloma [7].

- Nuclear Translocation Inhibitors: Small molecules like SN50 can block the nuclear import of NF-κB [7].

- Immunotherapy: Checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapies can alter the cytokine milieu, subsequently reshaping the activity of the NF-κB/STAT/IRF network in the tumor microenvironment [7].

The cross-talk between NF-κB, STATs, and IRFs represents a central regulatory module in inflammation and immunity. Their interactions—through direct complex formation, mutual regulation, and chromatin-level cooperation—create a robust yet flexible network that integrates diverse signals to mount precise transcriptional responses. Comparative analysis reveals that while each family has unique structural features and activation triggers, their functional synergy is what ultimately dictates immunological outcomes. The continued elucidation of these networks, powered by the sophisticated experimental methodologies detailed herein, is crucial for understanding complex diseases and developing the next generation of immunomodulatory therapeutics. Future research, particularly single-cell and multi-omics approaches, will further illuminate the contextual dynamics of this critical transcriptional interplay.

From Bench to Bedside: Methods for Quantifying Transcription Factor Activity in Research and Clinical Practice

DNA-Binding Assays (EMSA, ELISA) for Direct Activity Measurement

Transcription factors (TFs) are pivotal proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to regulate gene expression, serving as crucial mediators in inflammatory pathways. In the context of inflammatory marker research, accurately measuring the DNA-binding activity of TFs such as NF-κB, STAT family members, and NLRP3 provides critical functional insights into immune responses and disease mechanisms [37] [38]. Direct assessment of TF-DNA interactions enables researchers to understand how these factors orchestrate inflammation in conditions ranging from autoimmune disorders to cancer. Among the various techniques available, the Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) and DNA-Protein-Interaction Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (DPI-ELISA) have emerged as foundational methods for characterizing these molecular interactions in vitro. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key methodologies, supporting informed selection for specific research applications in transcription factor studies.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as gel shift or gel retardation assay, is based on the principle that protein-DNA complexes migrate more slowly than free DNA fragments during non-denaturing gel electrophoresis [39] [40]. This technique provides a direct qualitative and quantitative means to detect sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, with the retardation effect increasing with the number of proteins bound to the DNA [39]. EMSA can resolve complexes of different stoichiometry or conformation, and the protein source may be a crude nuclear or whole cell extract, in vitro transcription product, or purified preparation [40].

DNA-Protein-Interaction ELISA (DPI-ELISA) utilizes an ELISA-based platform where biotinylated DNA probes containing the TF binding site are immobilized on streptavidin-coated plates [41]. The binding of transcription factors to these immobilized probes is then detected using protein-specific antibodies conjugated to enzymes, producing a colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent signal [41]. This method offers significant advantages in throughput and safety compared to radioactive EMSA protocols.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of EMSA and DPI-ELISA

| Feature | EMSA | DPI-ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Separation based on size/charge in gel | Solid-phase immobilization and antibody detection |

| Throughput | Lower (limited by gel capacity) | Higher (96-well plate format) |

| Detection Method | Radioactive, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent labeling | Colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent detection |

| Sensitivity | High (can detect fmol amounts) | Very high (10-fold increased sensitivity vs EMSA) |

| Quantification | Quantitative (phosphorimaging) | Highly quantitative (spectrophotometry/fluorometry) |

| Sample Requirements | Crude extracts to purified proteins | Best with purified proteins or defined extracts |

| Key Applications | Identification of sequence-specific binding, complex stoichiometry, binding affinity | High-throughput screening, quantitative binding studies, characterization of binding specificity |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Transcription Factor Binding Studies

| Performance Metric | EMSA | DPI-ELISA | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Specificity | High (with appropriate controls) | High (with antibody confirmation) | Comparable specificity for AtbZIP63 and AtWRKY11 binding [41] |